Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt (1798-1885)

Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt was born at Blakesley in Northamptonshire on September 8th, 1798, the child of Henry Uthwatt Uthwatt (formerly Andrewes) and Judith Yates. Upon the death of his brother William he had inherited in 1877 the manor at the advanced age of 79, though had spent much of his life distanced from the family; it was only when he came into his inheritance that he was required to adopt the surname Uthwatt. Records of his movements and life are fragmentary and not entirely clear, so for instance he cannot be found as yet on the 1841 census, but can be identified on the Isle of Mann census in 1851, under the name Thomas Andrewes. He is described as a “Landed proprietor.”

However, it seems certain that he trained (or intended to train) as a solicitor, as we have an incontrovertible piece of evidence in the shape of his Articles of Clerkship, a document naming both himself and his mother Judith. Dated September 30th, 1815, this document tells us that Augustus was to be apprenticed to the firm of Hearn and Hearn in Buckingham, who appear to have been acting as the family solicitor.

A difficult man to pin down

Augustus cannot be found on the 1861 census and when his son Henry Manning Andrewes was married in 1870, Augustus’s profession was listed on the marriage record as Gentleman. When next we pick up his trail on the 1871 census, Augustus is living with his wife and two daughters in Lambeth, London, with his profession described as “own account”, which meant he was living without apparent income – likely then to be savings or inherited money. There is no sign then that he was making use of his professional qualification as a solicitor, presuming that he achieved this.

If that all sounds somewhat vague and mysterious, you’d be right; he would after his death be described as “hiding”, but from whom, and why? Augustus certainly seems to have been living a rather shadowy and markedly strange life, which in the fulness of time would become the source of much speculation and drama.

But for now, the elderly Augustus found himself the owner of a manor house that he seemed not greatly invested in, since in 1879 he appears to have decided on a clear-out. The Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of Saturday May 17th carries an advert placed by the auctioneer George Bennett announcing that there would be sale of, “the valuable contents of Great Linford Place.” Sales like this seem to have been a recurring feature of a change of ownership at the manor, and one cannot avoid thinking that generation by generation, the accumulated belongings (and wealth and history) of the family was being whittled away. This latest sale does also coincide with a change of use for the manor house, as the Uthwatts vacated to make way for the arrival of Slade’s Girls’ School, which was to occupy the building until 1883. However, the Slades were soon forced to move on as Augustus then decided to allow Anna Maria Uthwatt, widow of his brother Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt and her son William to occupy the manor rent free.

This certainly casts Augustus in a positive light, but there seems to have been another side to him, notably a reluctance to be pinned down on official paperwork. He resumes his disappearing act in the 1881 census, with no sign of him either as an Uthwatt or an Andrewes anywhere in the country. We do know however that he died in London at 4 Mecklenburgh Square, St Pancras, where according to the probate record also lived his daughters Augusta and Elizabeth; they and their father are not however there on the 1881 census. The same probate record also gives two previous addresses for Augustus, 39 Sutherland Street, Walworth Road in the county of Suffolk and 183 Hampstead-Road; this was clearly a man who did not want to linger long in the same place.

He died February 13th, 1885, and was buried at Southwark, London on the 20th, so no grand return and interment at Great Linford, as was the case with several previous generations. His personal estate was also surprisingly small, just £1,781, 9 shillings and 11 pence. What happened to the proceeds from the sale of 1879, or was this the residue?

If that all sounds somewhat vague and mysterious, you’d be right; he would after his death be described as “hiding”, but from whom, and why? Augustus certainly seems to have been living a rather shadowy and markedly strange life, which in the fulness of time would become the source of much speculation and drama.

But for now, the elderly Augustus found himself the owner of a manor house that he seemed not greatly invested in, since in 1879 he appears to have decided on a clear-out. The Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of Saturday May 17th carries an advert placed by the auctioneer George Bennett announcing that there would be sale of, “the valuable contents of Great Linford Place.” Sales like this seem to have been a recurring feature of a change of ownership at the manor, and one cannot avoid thinking that generation by generation, the accumulated belongings (and wealth and history) of the family was being whittled away. This latest sale does also coincide with a change of use for the manor house, as the Uthwatts vacated to make way for the arrival of Slade’s Girls’ School, which was to occupy the building until 1883. However, the Slades were soon forced to move on as Augustus then decided to allow Anna Maria Uthwatt, widow of his brother Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt and her son William to occupy the manor rent free.

This certainly casts Augustus in a positive light, but there seems to have been another side to him, notably a reluctance to be pinned down on official paperwork. He resumes his disappearing act in the 1881 census, with no sign of him either as an Uthwatt or an Andrewes anywhere in the country. We do know however that he died in London at 4 Mecklenburgh Square, St Pancras, where according to the probate record also lived his daughters Augusta and Elizabeth; they and their father are not however there on the 1881 census. The same probate record also gives two previous addresses for Augustus, 39 Sutherland Street, Walworth Road in the county of Suffolk and 183 Hampstead-Road; this was clearly a man who did not want to linger long in the same place.

He died February 13th, 1885, and was buried at Southwark, London on the 20th, so no grand return and interment at Great Linford, as was the case with several previous generations. His personal estate was also surprisingly small, just £1,781, 9 shillings and 11 pence. What happened to the proceeds from the sale of 1879, or was this the residue?

A shocking revelation

And here might end the story, but for a very curious postscript. Upon his death, the estate was to pass to William, the son of Augustus’s brother, Edolph, but out of the blue came an extraordinary counterclaim, that Augustus had succeeded in concealing with some cunning and guile the existence of a wife and family, and now one of his sons, a Henry Manning Uthwatt, was determined to lay claim to the estate. Such it seems was his certainty of his rights in thus matter, that he had changed his name by deed poll to Uthwatt, as had been announced in the London Evening Standard of June 1st, 1885.

I HENRY UTHWATT, of Gloucester Cottage, Bayham-street, in the county of Middlesex, gentleman, here tofore called Henry Andrewes and distinguished by the name of HENRY ANDREWES, hereby Give Notice, that by Deed Poll under my hand and seal dated the 25th day of April, 1885, and enrolled in the Chancery Division of her Majesty’s High Court of Justice, I did, in pursuance of the direction in that behalf contained in the last will and testament of Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, late of Great Linford Place, in the county of Bucks, Esquire, dated the 20th day of December, 1855, ASSUME and TAKE upon myself the SURNAME of “UTHWATT" only, in the place and stead of my former name of Andrewes. And I hereby Give further Notice, that I shall from henceforth in all deeds, instruments, and writings, and for all other purposes whatsoever, write and style myself, and continue to call myself, and to be called and known by the surname of " Uthwatt" only. As Witness my hand this 29th day of May. 1885. HENRY UTHWATT. Witness H. CLIFFORD GOSNELL. Solicitor, 64, Finsbury-pavement, London, E.C.

Thus armed with his new name, the case reached the High Court in London, and in testimony delivered by a variety of witnesses, a tale worthy of Downton Abbey unfolded.

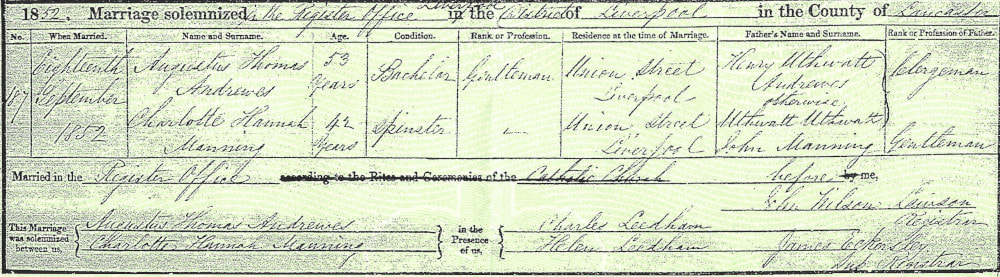

Augustus did indeed have a wife and five children; three daughters and two sons. His wife was named Charlette Hannah Manning, and the court case hinged on whether their son Henry, born May 27th 1844, was a legitimate heir, and specifically that his parents had been married at the time of his birth, for an illegitimate birth would invalidate any claim. A marriage certificate could not be produced in court, despite there having been an extensive search for one, so Henry’s claim rested on the contention that he could prove by other means that his parents had been married. A succession of witnesses were produced that painted a conflicting picture of Augustus, as loving husband and father, yet at the same time willing to go to extraordinary lengths to hide his children from the rest of the family. The motives for this decades long deception could only be speculated upon, but the Judge concluded that Augustus lacked the courage to admit to his children that they were illegitimate, even though it must have been obvious to them that they were. That he equally made every effort to promote William Uthwatt as the successor to the Great Linford estate seemed a particularly damning inditement as to his thinking, and so lacking the crucial marriage certificate, the Judge ruled against Henry’s claim.

But there was a marriage certificate, and had it been produced in court, it would have fatally holed Henry’s case below the waterline. The certificate is damning, with the marriage taking place at a Liverpool register office on September 18th, 1852, and naming Augustus’s father as Henry Uthwatt Andrewes, “otherwise Uthwatt Uthwatt.” Clearly then this is the missing certificate, and armed with this new evidence, we can say with certainty that only Augustus and Charlotte’s youngest child, Charlotte Hannah Andrewes, born 1854, could be deemed legitimate in the eyes of the law, though of course as a female she would not have been able to inherit.

Augustus did indeed have a wife and five children; three daughters and two sons. His wife was named Charlette Hannah Manning, and the court case hinged on whether their son Henry, born May 27th 1844, was a legitimate heir, and specifically that his parents had been married at the time of his birth, for an illegitimate birth would invalidate any claim. A marriage certificate could not be produced in court, despite there having been an extensive search for one, so Henry’s claim rested on the contention that he could prove by other means that his parents had been married. A succession of witnesses were produced that painted a conflicting picture of Augustus, as loving husband and father, yet at the same time willing to go to extraordinary lengths to hide his children from the rest of the family. The motives for this decades long deception could only be speculated upon, but the Judge concluded that Augustus lacked the courage to admit to his children that they were illegitimate, even though it must have been obvious to them that they were. That he equally made every effort to promote William Uthwatt as the successor to the Great Linford estate seemed a particularly damning inditement as to his thinking, and so lacking the crucial marriage certificate, the Judge ruled against Henry’s claim.

But there was a marriage certificate, and had it been produced in court, it would have fatally holed Henry’s case below the waterline. The certificate is damning, with the marriage taking place at a Liverpool register office on September 18th, 1852, and naming Augustus’s father as Henry Uthwatt Andrewes, “otherwise Uthwatt Uthwatt.” Clearly then this is the missing certificate, and armed with this new evidence, we can say with certainty that only Augustus and Charlotte’s youngest child, Charlotte Hannah Andrewes, born 1854, could be deemed legitimate in the eyes of the law, though of course as a female she would not have been able to inherit.

Did Henry know there was a certificate, and did he hide this fact? None of the children claimed to know with certainty the date of their parent’s marriage or crucially where it had been held; was this a genuine lapse of knowledge, or were they all in on a scheme to try and wrest control of the estate from its rightful owner?

What does not seem to have been touched upon in the court’s deliberations is Augustus’s motive for delaying his marriage. He cannot have been unaware that if he was to have children, they would have some claim to the estate, and equally as a solicitor he must have known that if those children were born illegitimately, they would forfeit that inheritance. Yet despite this, clearly something had given him pause to commit to the relationship. It is a mystery he took to his grave.

The accounts of the case, which took up copious column inches in numerous newspapers provide much fascinating detail on the machinations of Augustus and the life of the Uthwatts. An annotated transcription from the Buckingham Advertiser of the case of Andrewes v Uthwatt can be read here.

What does not seem to have been touched upon in the court’s deliberations is Augustus’s motive for delaying his marriage. He cannot have been unaware that if he was to have children, they would have some claim to the estate, and equally as a solicitor he must have known that if those children were born illegitimately, they would forfeit that inheritance. Yet despite this, clearly something had given him pause to commit to the relationship. It is a mystery he took to his grave.

The accounts of the case, which took up copious column inches in numerous newspapers provide much fascinating detail on the machinations of Augustus and the life of the Uthwatts. An annotated transcription from the Buckingham Advertiser of the case of Andrewes v Uthwatt can be read here.