The otterhounds and kennels at Great Linford

There were “otterhounds” in medieval England, though there is no firm record of what they would have looked like, or even of what breeds they might have been. The modern otterhound is known to be big, boisterous and affectionate and as befits their hunting pedigree have a dense shaggy oily coat, webbed feet and an affinity for swimming. Supremely specialised, their acute sense of smell is sensitive enough to track an otter underwater and sniff out very old scent trails, known as a drag. Otterhounds are now considered an endangered breed, with only some 600 left in the world.

The hounds of the Bucks Otter Hunt are thought to have originated from Wavendon, where a Henry Hoare had hunted with them for several years. In September of 1889 he put the pack up for sale, and in due course they found their way to Great Linford. The sale notice carried in the September edition of the Field Magazine provides a useful account of the pack as it was then, though of course we do not know if this is precisely the composition of the pack that was subsequently moved to Great Linford.

OTTER HOUNDS – For SALE, the entire PACK, Four Couple pure-bred rough Otter Hounds, a couple of Foxhounds, and a Couple of Welsh Hounds, and Three Couples pure-bred rough Otter Hound Puppies, unentered – Apply H. Hoare, Esq., Wavendon, Woburn, Beds.

The pack was described (accurately it seems from the above description) as, “a rather short and mixed lot” in a brief history published in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News of April 21st, 1900. The reference to “couples” is an interesting one, a term used also in fox hunting to count the hounds in a pack, so for instance in the above sale notice, there are a total of nine couples, so 14 dogs in total.

Rather confusing matters, a history of the pack in the Wolverton Express of August 13th, 1954, offers that in the earliest days of the hunt, dogs had been obtained from the Hawkstone Otter Hunt from Ludlow, whose founding certainly predates the Bucks pack. These were described as the “old rough coated variety.” It is unclear then if this refers to the dogs obtained from Wavendon, or if the pack at Great Linford was latter supplemented with dogs from the Hawkstone hunt.

An interesting piece in the Stamford Mercury of March 1st, 1895, provides some further insight into the composition of the pack, and the breeding policies. “Mr Uthwatt has now 18 couples of hounds, of which 14 are entered and reliable, and four couple are well grown young hounds ready to be put forward. Unlike many masters of the present day, Mr Uthwatt adheres almost entirely to the old and pure type of hound, and his pack has lately done as well on the show bench as last season at work.”

The purity of the pack is further confirmed by Jack Ivester Lloyd. Writing in his 1973 book Hounds of Britain, he states that at one time the pack was entirely comprised of otterhounds, and adds the following evocative recollection. “Never have I heard deeper or more impressive hound music than the cry of a pack of true otterhounds ringing through a rivervalley.”

The Uthwatts clearly took their breeding programme seriously, as two of the pack were awarded prizes at Crufts in 1893, a “second prize, reserve” and a breeders prize for the dogs Dairy-maid and Linford Barmaid.

A 1905 list of packs hunting in 1905 and carried in the Field Magazine makes mention that the Bucks otterhounds were by then composed of 17 couples, so in effect 34 dogs, a significant increase on the size of the pack in 1889.

A pack would generally also be accompanied by some terriers, whose role was to dive into a submerged otter den (typically known as a holt or couch) should the prey seek refuge there. The Terrier would then flush out the otter so the hunt could be resumed.

In early March of 1909, it was reported that Gerard Uthwatt was promoting what he hoped would become an annual sale of otterhounds. The sale was to occur at the auctioneers Aldridges located on St. Martin’s Lane in London. The sale was intended to bring together masters and breeders from as far afield as the United States, where there was growing interest in otter hunting. There is no indication if the goal of an annual sale was achieved, though it is possible to find further sales relating to otterhounds at Aldridges, including one later in 1909 that included several dogs belonging to Gerard Uthwatt.

The Wolverton Express of August 13th, 1954 offers the following on the history of the pack. “After the first world war, they became a mixed pack of foxhounds and otterhounds, but later Welsh blood was introduced with great success.” The same article goes on to explain that by 1954 the pack was comprised of foxhounds and pure bred otterhounds, 24 couples in all. Writing in the book Vive La Chase, a collection of writings on hunting published in 1987, Waddy Wadsworth offers the opinion that the pure bred otterhound was actually unsuited to the job, and though they had a superb sense of smell, this was actually a liability, as they would tend to fixate on a scent that might be weeks old. Wadsworth therefore recommended the use of foxhounds, as they were likely to follow the drag.

Clearly having a large number of dogs kennelled together came with inherent risks. Despite the earlier description of the otterhounds as “boisterous and affectionate”, dogs trained to kill could still easily turn nasty. In fact, the local artist Thomas Ivester LLoyd wrote in his book Hounds (published 1934) that, “some strains were very savage in kennel and muzzles had sometimes to be used when they were left.”

Sadly it seems that Lloyd was all too correct in his assessment, as was tragically proven in the case of an attack on 6 year old William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt, which occurred in May of 1903. As reported in Croydon's Weekly Standard of the 9th, the unfortunate lad had been crossing the yard from the manor to the otterhound kennels with a telegram in hand, when he was set upon by the fox terriers, which in turn attracted the ire of the otterhounds who were roaming free at the time. By the time Gerard Uthwatt had beat off the animals, William had been bitten on the legs very badly, necessitating a visit from a Doctor Bull of Stony Stratford. Clearly however the experience did not sour young William on the hounds, as he went on to become master of the pack.

Keeping the dogs in close quarters might also increase the chances of a disease outbreak, hence we find a report in 1955 that hunts were to be suspended due to an occurrence of distemper at the kennels.

One thing that does become apparent from perusing accounts of the hunts, is that the names of the dogs are sometimes provided and in one particular case from March of 1900, we even gain a small insight into their abilities and personalities.

Rather confusing matters, a history of the pack in the Wolverton Express of August 13th, 1954, offers that in the earliest days of the hunt, dogs had been obtained from the Hawkstone Otter Hunt from Ludlow, whose founding certainly predates the Bucks pack. These were described as the “old rough coated variety.” It is unclear then if this refers to the dogs obtained from Wavendon, or if the pack at Great Linford was latter supplemented with dogs from the Hawkstone hunt.

An interesting piece in the Stamford Mercury of March 1st, 1895, provides some further insight into the composition of the pack, and the breeding policies. “Mr Uthwatt has now 18 couples of hounds, of which 14 are entered and reliable, and four couple are well grown young hounds ready to be put forward. Unlike many masters of the present day, Mr Uthwatt adheres almost entirely to the old and pure type of hound, and his pack has lately done as well on the show bench as last season at work.”

The purity of the pack is further confirmed by Jack Ivester Lloyd. Writing in his 1973 book Hounds of Britain, he states that at one time the pack was entirely comprised of otterhounds, and adds the following evocative recollection. “Never have I heard deeper or more impressive hound music than the cry of a pack of true otterhounds ringing through a rivervalley.”

The Uthwatts clearly took their breeding programme seriously, as two of the pack were awarded prizes at Crufts in 1893, a “second prize, reserve” and a breeders prize for the dogs Dairy-maid and Linford Barmaid.

A 1905 list of packs hunting in 1905 and carried in the Field Magazine makes mention that the Bucks otterhounds were by then composed of 17 couples, so in effect 34 dogs, a significant increase on the size of the pack in 1889.

A pack would generally also be accompanied by some terriers, whose role was to dive into a submerged otter den (typically known as a holt or couch) should the prey seek refuge there. The Terrier would then flush out the otter so the hunt could be resumed.

In early March of 1909, it was reported that Gerard Uthwatt was promoting what he hoped would become an annual sale of otterhounds. The sale was to occur at the auctioneers Aldridges located on St. Martin’s Lane in London. The sale was intended to bring together masters and breeders from as far afield as the United States, where there was growing interest in otter hunting. There is no indication if the goal of an annual sale was achieved, though it is possible to find further sales relating to otterhounds at Aldridges, including one later in 1909 that included several dogs belonging to Gerard Uthwatt.

The Wolverton Express of August 13th, 1954 offers the following on the history of the pack. “After the first world war, they became a mixed pack of foxhounds and otterhounds, but later Welsh blood was introduced with great success.” The same article goes on to explain that by 1954 the pack was comprised of foxhounds and pure bred otterhounds, 24 couples in all. Writing in the book Vive La Chase, a collection of writings on hunting published in 1987, Waddy Wadsworth offers the opinion that the pure bred otterhound was actually unsuited to the job, and though they had a superb sense of smell, this was actually a liability, as they would tend to fixate on a scent that might be weeks old. Wadsworth therefore recommended the use of foxhounds, as they were likely to follow the drag.

Clearly having a large number of dogs kennelled together came with inherent risks. Despite the earlier description of the otterhounds as “boisterous and affectionate”, dogs trained to kill could still easily turn nasty. In fact, the local artist Thomas Ivester LLoyd wrote in his book Hounds (published 1934) that, “some strains were very savage in kennel and muzzles had sometimes to be used when they were left.”

Sadly it seems that Lloyd was all too correct in his assessment, as was tragically proven in the case of an attack on 6 year old William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt, which occurred in May of 1903. As reported in Croydon's Weekly Standard of the 9th, the unfortunate lad had been crossing the yard from the manor to the otterhound kennels with a telegram in hand, when he was set upon by the fox terriers, which in turn attracted the ire of the otterhounds who were roaming free at the time. By the time Gerard Uthwatt had beat off the animals, William had been bitten on the legs very badly, necessitating a visit from a Doctor Bull of Stony Stratford. Clearly however the experience did not sour young William on the hounds, as he went on to become master of the pack.

Keeping the dogs in close quarters might also increase the chances of a disease outbreak, hence we find a report in 1955 that hunts were to be suspended due to an occurrence of distemper at the kennels.

One thing that does become apparent from perusing accounts of the hunts, is that the names of the dogs are sometimes provided and in one particular case from March of 1900, we even gain a small insight into their abilities and personalities.

First and foremost comes that veteran “Driver”; what he does not know about otter catching would be very little good to his progeny. “Booser,” a magnificent animal, a trifle noisy on the drag, but a demon at water work. “Bellman” and “Boadsman” two sons of “Driver” would be a couple hard to match, and I must not forget old “Daylight” and “Ruby.”

Despite then what we would now consider the awful work they were being encouraged to engage in (a whip in 1968 is quoted as saying that if the hounds lose their taste for blood, they’ll become like pets), the dogs were clearly much valued and admired by the hunting fraternity, though it is worthwhile dwelling on the following words written by Richard Clapham in The Book of the Otter (published 1922) concerning the last stand of a cornered otter. “Perhaps he takes refuge in a holt, and is then bolted by the terriers. Anyway, if things go right, the time comes when he can do no more, and he dies fighting on the shallows, leaving his mark on nearly every hound.” Clearly then, the otter was not the only one to suffer from this “sport.”

The hounds on the move

The otterhounds were seasoned travellers, such that it was said that they “hunted half of England”, and certainly it is not unusual to find accounts of hunts taking place in many different counties each year. The book Otters and Otter-hunting by L.C.R Cameron (1904) provides the following list of counties visited and waters hunted at that time.

Water hunted: Welland, Ousel, Alne, Blythe, Nene, Cherwell, Ock, Ouse, Windrush, Guash, Avon, Thame, Tove, Learn, Evenlode, Arrow, Kym, Itchen, Cole, Bow; in Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Northants, Oxfordshire, Rutland, and Warwickshire.

Having a train station in the village and so close to the kennels was undoubtedly of great convenience, and we can get a sense of the distances travelled in a typical season by availing ourselves of newspaper reports.

Unless very close to their home kennels and thus able to make the return trip in a day, we find the pack typically arriving in a particular area and conducting hunts over many consecutive days, finding billets locally and moving from one waterway to another. Hence we find for instance that in April of 1904, the pack arrived in the district of Stamford, Lincolnshire, where they hunted at Fotheringhay, Perry Mill, Tallington and Ketton, to name but a few in a visit lasting a week. This seems quite a feat of organisation, and also speaks to the welcome afforded the hunt by local landowners.

1904 looks to have been a particularly busy year for the hunt, as along with Lincolnshire, we find them in Bedfordshire, Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire; the latter being a particularly popular destination with at least 3 visits made in the year. We know from one of these visits something of the logistics required, with the hounds brought to Rugby by train, and then by van the six miles to Bretford. The hunt did have a hiatus on the death in August of Anna Maria Uthwatt, wife of hunt master William, but after a period of mourning the hunt resumed its activities, the season ending in Stamford on a curious note with the death of a polecat that had been pursued and dispatched in the mistaken belief that it was an otter. Such was the novelty of this event that the story was carried in numerous newspapers across the country.

Water hunted: Welland, Ousel, Alne, Blythe, Nene, Cherwell, Ock, Ouse, Windrush, Guash, Avon, Thame, Tove, Learn, Evenlode, Arrow, Kym, Itchen, Cole, Bow; in Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Lincolnshire, Northants, Oxfordshire, Rutland, and Warwickshire.

Having a train station in the village and so close to the kennels was undoubtedly of great convenience, and we can get a sense of the distances travelled in a typical season by availing ourselves of newspaper reports.

Unless very close to their home kennels and thus able to make the return trip in a day, we find the pack typically arriving in a particular area and conducting hunts over many consecutive days, finding billets locally and moving from one waterway to another. Hence we find for instance that in April of 1904, the pack arrived in the district of Stamford, Lincolnshire, where they hunted at Fotheringhay, Perry Mill, Tallington and Ketton, to name but a few in a visit lasting a week. This seems quite a feat of organisation, and also speaks to the welcome afforded the hunt by local landowners.

1904 looks to have been a particularly busy year for the hunt, as along with Lincolnshire, we find them in Bedfordshire, Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire and Warwickshire; the latter being a particularly popular destination with at least 3 visits made in the year. We know from one of these visits something of the logistics required, with the hounds brought to Rugby by train, and then by van the six miles to Bretford. The hunt did have a hiatus on the death in August of Anna Maria Uthwatt, wife of hunt master William, but after a period of mourning the hunt resumed its activities, the season ending in Stamford on a curious note with the death of a polecat that had been pursued and dispatched in the mistaken belief that it was an otter. Such was the novelty of this event that the story was carried in numerous newspapers across the country.

The kennels

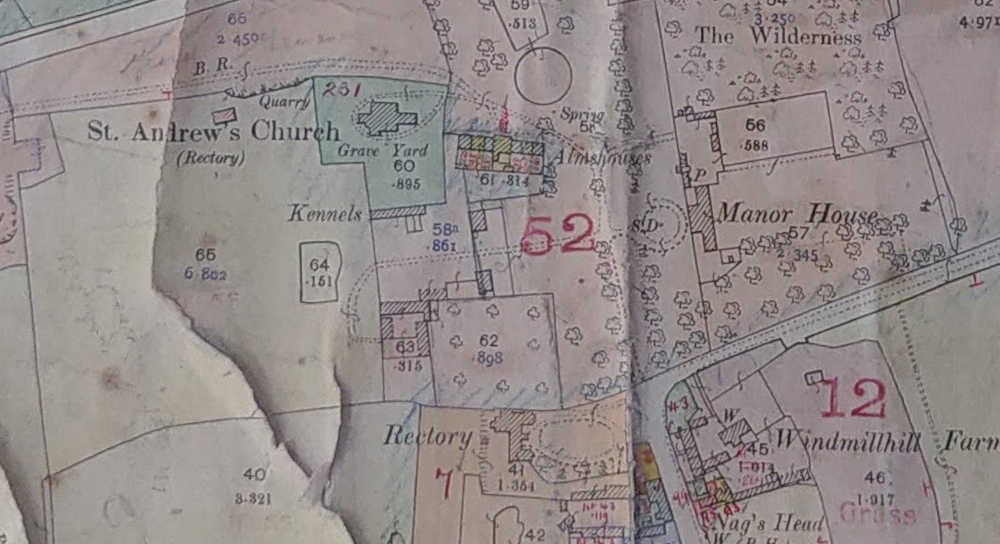

The otterhounds were originally kennelled at a building originally within the grounds of the manor, but which have since been replaced by workshops for the Milton Keynes Arts Centre. We do not have a close up picture of the kennels, but it is clear from the few photographs available that it was a substantial block with thatched roofs. The 1911 census seems to indicate that alongside accommodation for the dogs, there was also lodging for at least one member of the hunt staff.

The building appears to have fallen into complete disrepair by the time the Milton Keynes Development Corporation purchased the estate in the early 1970s and was subsequently demolished. The picture below is interesting, as it shows what we can presumed to be a yard for the use of the dogs, and that there were eight distinct rooms.

Exactly how long it was home to the otterhounds is uncertain, but it is clear from the available evidence that the dogs were moved sometime on or before 1953 to kennels at The Black Horse Inn. We can say this with certainty as the year-end report for the Bucks Otter Hunt in 1953 (reproduced in the book Vive La Chase) clearly indicates that the dogs were being kennelled there. Several residents of the village also recall that the otterhounds were kennelled at the Black Horse, but no earlier record has yet come to light that allows us to pinpoint precisely when the pack was moved from the manor grounds.

We can narrow down the date of the move. That there were still kennels within the manor grounds in 1910 seems incontrovertible, as they are clearly labelled as such on the 1910 tax map, and are still recorded in the same location on the 1924 and 1944 OS maps.

We can narrow down the date of the move. That there were still kennels within the manor grounds in 1910 seems incontrovertible, as they are clearly labelled as such on the 1910 tax map, and are still recorded in the same location on the 1924 and 1944 OS maps.

The Bedfordshire Times and Independent of February 3rd, 1933 reports on a general meeting at which a vote was proposed to thank the master for providing the kennel accommodation, and “that the Master had also re-drained and modernized all the yards at his own expense.” It would seem then that the work referred to was to the kennels in the manor grounds. The 1952 OS map again labels the kennels in the same location, but by time of the OS map published in 1958, the labelling has been dropped. So the available evidence points to the otterhounds having been moved circa 1952/53. Frustratingly, the OS map of 1958 does not show kennels at the Black Horse (though we must presume they were there), and while we can be reasonably confident as to when the move occurred, the reasons behind it must for now remain a mystery.

The Bucks Otter Hounds remained at the Black Horse kennels until 1972, this according to a personal recollection supplied to the author. The problem was noise; new publicans had arrived that year, and complained about the dogs. It might have even been worse than imagined, as according to Waddy Wadsworth in his book A sporting life, the North Bucks Beagles (who hunted hares) were kennelled at the time alongside the otterhounds, in which case the din must have been cacophonous indeed.