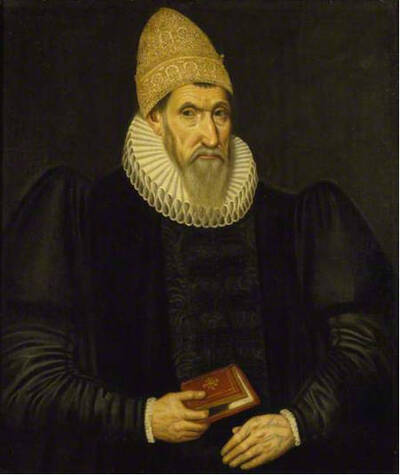

The Reverend Richard Napier

|

The Reverend Richard Napier, or Sandy as he was known to friends and acquaintances, was for over 40 years the rector of Great Linford, but also more famously a practitioner of astrological medicine who became wealthy from his thriving practice, which he conducted from the village rectory.

Born in Exeter on May 4th, 1559, during the reign of Elizabeth the 1st, his father was Alexander Napier (also known as Sandy) and his mother was Ann (or Agnes) Buchley. Though they had been living in Devon from about 1540, the family claimed an old Scottish heritage from the lairds of Merchiston, whose properties included a castle outside of Edinburgh. We do not know how Alexander and Ann came to reside in Exeter, and next to nothing of their lives, though Alexander was described as a merchant of Exeter and London. Richard appears to have been attracted at an early age to astrological, mystical and occult studies, which might not be so surprising if we consider who his paternal 1st cousin was. |

John Napier - a possible early influence

|

John Napier (born 1550 in Edinburgh) was also known as “Marvellous Merchiston”, and had famously named and popularised the mathematical concept of logarithms. He also designed a calculating machine known as “Napier’s Bones”, but it is arguably John’s interest in the occult that may have had some influence on Richard. If not, it can certainly be argued that something magical ran in the family.

No evidence has presented itself to suggest they knew each other well or corresponded, but tellingly John was thought to have dabbled in alchemy (most famously recognized for its flawed ambition of turning lead into gold) and necromancy, a form of magic that involved communicating with the dead. Some of John Napier’s neighbours in Merchiston had even (dangerously) accused him of being a sorcerer in league with the devil, though it seems more likely that his extremely shrewd mind singled him out as inexplicable and strange. |

On one occasion, suspecting a servant of being a thief, he had covered a rooster with soot and sending his servants into a darkened room, had instructed them to pet the bird, which he claimed would crow when the thief touched it. On leaving the room, Napier examined their hands and declared the thief to be the one with clean hands, for he was surely the one who had been too frightened to touch the bird. The logic was brilliant, but tongues would surely have wagged at this unorthodox thinking.

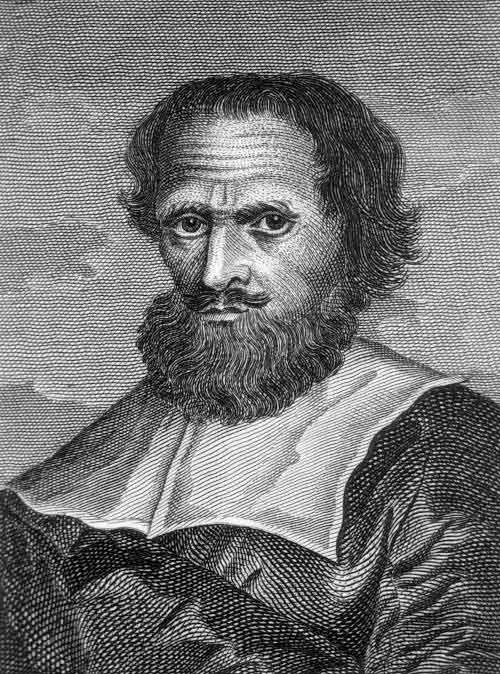

Simon Forman - an unlikely friend

|

But even if his cousin John had not been a direct influence on his thinking, Richard Napier would meet another out of the box thinker who very definitely shaped his future, becoming a life-long friend and associate. Simon Forman (born 1552) was someone who skirted perilously close to the margins of acceptable behaviour in Elizabethan society; frequently at odds with the authorities and known as an incorrigible womaniser. After his death (which he is said to have predicted to the day, hour and place) he was posthumously implicated in a scandalous poisoning case, and so it does seem odd that a man like Napier, seemingly destined to become a respectable provincial clergyman, would come to find in this wild figure a kindred spirit.

Forman to his credit was a self-made man from a poor background, such that on the death of his father he had to abandon his schooling aged 11 to become apprentice to a trader in salt, cloth and herbal medicines. It seems highly likely that this began his interest in medicine, and after disputes with his master’s wife led to the termination of his apprenticeship, he found his way to Oxford where he studied as a poor scholar. |

After a stint as a teacher, in the early 1590s he established himself in London as an unlicensed medical practitioner, though his techniques and cures were far removed from modern ideas, relying primarily on astrology to diagnose his patient’s ailments. Respectable medical science was still in its infancy and in London very much the preserve of the College of Physicians, who took an extremely dim view of Forman and his self-taught interest in occult matters, such that they brought multiple charges against him for quackery, a derogatory term for a medical fraud. For instance, on November 7th, 1595, he was examined by the college and found to be, “completely ignorant. He confessed that he had read no medical writers save Cockis, 'an English writer, a very obscure man, absolutely unknown and certainly of no merit.' Was forced to confess that he practised medicine only by astrology. Was ignorant of the fundamentals.” For this he was imprisoned and fined £10.

Napier had taken a more conventional route in his education, matriculating (enrolling) at Exeter College in Oxford to study theology in 1577, admitted as a fellow in 1580 and achieving a BA in 1584 and an MA in 1586. On March 12th, 1590 he was ordained as the rector of Great Linford, a rapid and impressive progression that should have seen him settle into the quiet unassuming life of a country vicar. But a life in the pulpit was not something that seemed to suit Richard, such that a story is told (by a friend and visitor to the rectory named William Lilley) that he had broken down during a sermon and thereafter withdrew from preaching. He instead appointed curates, whom he paid and lodged in the rectory to carry out his ecclesiastical duties. This left him plenty of time to pursue his passion for medicine, and in 1597 began a long correspondence with Simon Forman, though few of the letters survive. Napier sought advice on difficult cases and alchemical and magical practices, with Forman sending ingredients and Napier reciprocating with gifts, such as in 1598 some cheeses which were gratefully received.

The two men also regularly visited with each other, Napier when staying with his brother Robert, who had established himself as a successful merchant in London and was trading in the Levant (broadly the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia.) Robert became extremely wealthy as a so called "Turkey Merchant" and purchased Great Linford manor in 1634, along with the advowson of the village church, which meant he had the right to appoint the resident clergyman. Robert was also almost certainly another source of medicinal ingredients for his brother.

Napier had taken a more conventional route in his education, matriculating (enrolling) at Exeter College in Oxford to study theology in 1577, admitted as a fellow in 1580 and achieving a BA in 1584 and an MA in 1586. On March 12th, 1590 he was ordained as the rector of Great Linford, a rapid and impressive progression that should have seen him settle into the quiet unassuming life of a country vicar. But a life in the pulpit was not something that seemed to suit Richard, such that a story is told (by a friend and visitor to the rectory named William Lilley) that he had broken down during a sermon and thereafter withdrew from preaching. He instead appointed curates, whom he paid and lodged in the rectory to carry out his ecclesiastical duties. This left him plenty of time to pursue his passion for medicine, and in 1597 began a long correspondence with Simon Forman, though few of the letters survive. Napier sought advice on difficult cases and alchemical and magical practices, with Forman sending ingredients and Napier reciprocating with gifts, such as in 1598 some cheeses which were gratefully received.

The two men also regularly visited with each other, Napier when staying with his brother Robert, who had established himself as a successful merchant in London and was trading in the Levant (broadly the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia.) Robert became extremely wealthy as a so called "Turkey Merchant" and purchased Great Linford manor in 1634, along with the advowson of the village church, which meant he had the right to appoint the resident clergyman. Robert was also almost certainly another source of medicinal ingredients for his brother.

The curious appointment of Richard Napier

The question arises, how did a man of Scottish heritage, born in Exeter and educated in Oxford, come to be the Rector of a small Buckinghamshire parish? The answer seems to lie with a London merchant named Edward Kimpton, who in 1590 appears to have held the Advowson, the legal right to appoint the Rector of Great Linford. But why would he pick Napier to be Rector?

Edward had married a half-sister of Richard Napier named Katherine, so perhaps we can speculate that Edward had purchased the Advowson as a gift or favour to his wife. However, neither the lineage of Katherine or definitive proof of her subsequent marriage can be confirmed for certain. Only a few tantalising pieces of evidence can be found, principally in a biographical treatise published in 1900 that compiles information on a family name Marsh. Here we find information that Edward and Katherine had a daughter Elizabeth, who had married a Thomas Marsh. The biography elaborates:

Edward had married a half-sister of Richard Napier named Katherine, so perhaps we can speculate that Edward had purchased the Advowson as a gift or favour to his wife. However, neither the lineage of Katherine or definitive proof of her subsequent marriage can be confirmed for certain. Only a few tantalising pieces of evidence can be found, principally in a biographical treatise published in 1900 that compiles information on a family name Marsh. Here we find information that Edward and Katherine had a daughter Elizabeth, who had married a Thomas Marsh. The biography elaborates:

He married in 1589, Elizabeth, daughter and heir of Edward Kimpton, of London, Merchant Taylor, by Katherine, sister of the half-blood to Sir Robert Napier, Bart. (so cr. 1611), da of Alexander Napier, of Exeter and London, Merchant.

So here we have the evidence that Katherine had a different mother to Robert and Richard Napier. This then may be why she is so hard to locate and does not seem to figure in any histories of the family. The abbreviated reference above to “Bart. (so cr. 1611)” can be explained as follows: Bart is an abbreviation for Baronet and the date cited would be a reference to when he was elevated to the position. This is a fair match to Sir Robert Napier of Great Linford Manor, though it does appear to be a year out, as other sources give us a precise date for the appointment of November 25th 1612, though this may simply be an error in the former. Also, he was knighted in 1611, so here also we have potential for a muddling of dates. Adding further to our tally of evidence, both Elizabeth and Thomas Marsh were referenced at the proving of Edward’s will.

In a final interesting piece of additional circumstantial evidence, the will of an Edward Kimpton who died in 1608 does mention that he owned a “Free House” (unfortunately unnamed) in Newport Pagnell, so if this is our man, it certainly puts him doing business in the right vicinity. We are however missing a vital piece of evidence, any corroborating evidence for the parentage of Katherine; was she the result for instance of a second marriage by Alexander after the death of his first wife Ann Birchley. Unfortunately we lack even a date for Ann’s death, so this must remain speculation.

In a final interesting piece of additional circumstantial evidence, the will of an Edward Kimpton who died in 1608 does mention that he owned a “Free House” (unfortunately unnamed) in Newport Pagnell, so if this is our man, it certainly puts him doing business in the right vicinity. We are however missing a vital piece of evidence, any corroborating evidence for the parentage of Katherine; was she the result for instance of a second marriage by Alexander after the death of his first wife Ann Birchley. Unfortunately we lack even a date for Ann’s death, so this must remain speculation.

Diagnosis and cure

It was probably around 1597 that Napier began practicing as an astrological doctor, as this is the year that his first surviving case-book is dated. These represent an extraordinary record of his dealings with patients not just from Great Linford, but from far and wide, and representing all classes of society.

Luckily, Richard Napier’s case books (and those of Simon Forman which were bequeathed to him) were acquired by the famous collector Elias Ashmole, and can now be viewed online as part of the Bodleian Library’s Ashmole collection. Napier’s books are an extraordinary record that show in great detail his methodology in diagnosing and offering up remedies to his patients, covering both mental and physical maladies, and even matters such as loss and theft. His approach was heavily focused on astrology, but this was not the fortune telling most commonly offered today, but rather a branch known as horary astrology. This meant recording very precisely the date and time the patient asked a question, so unlike the more well-known form of astrology typically found in a modern newspaper, which takes as its starting point the date of birth, Napier was basing his calculations on the time of his consultation. He didn’t always stick to this rule; arguably a chart based on the outset of an illness would be more accurate, but in a world in which precise time keeping was a rarity and determining when you became ill was a matter of conjecture, the hoary method was by far the simpler option. Napier was not then predicting his patient’s future wellbeing, but trying to learn what heavenly bodies might be casting their malign influence at the time the patient presented him the symptoms.

Napier was though clearly using the same methods that had landed Forman in prison, and evidently the tone of his friend’s inditement was one of disdain by the medical authorities at his use of astrology. But Napier very obviously placed great store in the method; his case books are festooned with carefully drawn astrological charts for each consultation. However astrology was not his only tool for diagnosis, he also spoke to angels, most commonly Raphael. Napier would often retire into another room to invoke an angel, commonly asking for guidance on medicines or the likely outcome of a treatment, which were not always positive. For instance a young man named Michael Horwood from Newport Pagnell sought help in 1620 after passing blood for 5 weeks, but Raphael offered the bleak prognosis that, “he is likely to die with out recovery.” Napier’s reliance on celestial help was substantial and extended beyond medical queries to matters of prophesy, such as will a husband outlive a wife or a relative inherit lands?

Another diagnostic tool at Napier’s disposal was to look at the bodily excretions of his patients, typically their urine, a flask of which might be examined for colour, odour and any unnatural discharge. It was apparently routine for urine to be sent to Napier, so one can imagine a rider or coach clattering down the High Street with a flask, having sometimes come a considerable distance. For instance Napier records the arrival of a sample on October 7th 1606 from Wing, 13 miles from Great Linford. In this case he writes that the sample came from the First Baron Dormer, but makes the odd observation that it had been brought by the Baron’s wife without his consent. One must suppose that a poor servant would have been delegated to decant it in secret from a chamber pot.

Luckily, Richard Napier’s case books (and those of Simon Forman which were bequeathed to him) were acquired by the famous collector Elias Ashmole, and can now be viewed online as part of the Bodleian Library’s Ashmole collection. Napier’s books are an extraordinary record that show in great detail his methodology in diagnosing and offering up remedies to his patients, covering both mental and physical maladies, and even matters such as loss and theft. His approach was heavily focused on astrology, but this was not the fortune telling most commonly offered today, but rather a branch known as horary astrology. This meant recording very precisely the date and time the patient asked a question, so unlike the more well-known form of astrology typically found in a modern newspaper, which takes as its starting point the date of birth, Napier was basing his calculations on the time of his consultation. He didn’t always stick to this rule; arguably a chart based on the outset of an illness would be more accurate, but in a world in which precise time keeping was a rarity and determining when you became ill was a matter of conjecture, the hoary method was by far the simpler option. Napier was not then predicting his patient’s future wellbeing, but trying to learn what heavenly bodies might be casting their malign influence at the time the patient presented him the symptoms.

Napier was though clearly using the same methods that had landed Forman in prison, and evidently the tone of his friend’s inditement was one of disdain by the medical authorities at his use of astrology. But Napier very obviously placed great store in the method; his case books are festooned with carefully drawn astrological charts for each consultation. However astrology was not his only tool for diagnosis, he also spoke to angels, most commonly Raphael. Napier would often retire into another room to invoke an angel, commonly asking for guidance on medicines or the likely outcome of a treatment, which were not always positive. For instance a young man named Michael Horwood from Newport Pagnell sought help in 1620 after passing blood for 5 weeks, but Raphael offered the bleak prognosis that, “he is likely to die with out recovery.” Napier’s reliance on celestial help was substantial and extended beyond medical queries to matters of prophesy, such as will a husband outlive a wife or a relative inherit lands?

Another diagnostic tool at Napier’s disposal was to look at the bodily excretions of his patients, typically their urine, a flask of which might be examined for colour, odour and any unnatural discharge. It was apparently routine for urine to be sent to Napier, so one can imagine a rider or coach clattering down the High Street with a flask, having sometimes come a considerable distance. For instance Napier records the arrival of a sample on October 7th 1606 from Wing, 13 miles from Great Linford. In this case he writes that the sample came from the First Baron Dormer, but makes the odd observation that it had been brought by the Baron’s wife without his consent. One must suppose that a poor servant would have been delegated to decant it in secret from a chamber pot.

The four humours

Having discussed with the patient their symptoms, drawn their chart and sometimes examined bodily fluids and sought advice from an angel, Napier was now ready to pinpoint the problem and prescribe a cure. To do this, he looked to the writers of ancient Greece, principally Hippocrates and Galen, who had popularised the idea that the body contained what were called the four humours. In essence the theory as applied to medicine was that these humours needed to be in balance and harmony with each other, hence if one was deficient or had grown to excess, then illness was the likely outcome. On the other hand, a healthy and happy patient was said to be in “good humour.” Napier’s goal would have been to restore equilibrium to his patient’s humours.

The four humours were ascribed characteristics of mood, season and an element, such as air or water.

Armed with all this information, Napier was now ready to propose a course of action.

The four humours were ascribed characteristics of mood, season and an element, such as air or water.

- Black bile (melancholy) – Autumn – cold and dry – too much earth

- Yellow bile (aggression) – Summer – hot and dry – too much fire.

- Blood (believed produced by the liver – positive attributes) - Spring – hot and moist – too much air

- Phlegm (Apathy) – Winter – cold and moist – too much water. Where we get the word Phlegmatic, unemotional and calm.

Armed with all this information, Napier was now ready to propose a course of action.

Potions and Sigils

Napier had a number of options at his disposal for treatment. Most commonly he would prescribe a herbal treatment, which were often intended as purgatives to induce vomiting or bowel movements as this was seen as the best way to remove excess humours. One such prescription contained hiera logadil, lapis lazuli, hellebore, cloves, liquorice powder, diambre and pulvis sabcti, all to be infused in a solution of white wine and borage. The violent purge this triggered was said to be a cure for all melancholy and mopish people, so in this case it seems Napier had diagnosed an issue with the patients black bile. It is an interesting list of ingredients, which speaks to the exotic nature of Napier’s prescriptions, not least the liquorice, which is native to southern Europe and Asia and the lapis lazuli, which could well have come from Afghanistan.

The other principal cure offered by Napier were sigils. These were made of metal (often of tin or brass but sometimes silver or gold) and designed to be hung about the neck by a ribbon of taffeta or silk, or they could be worn on a ring or carried in a bag. The sigil would be inscribed with an astronomical symbol and had to be made at the right time and day to imbue them with the maximum potency of the astronomical object they depicted. Equally, the wearer had to use the sigil at the most opportune time as devised by Napier, again so as to maximise the heavenly power of the celestial object. Napier made great use of sigils, usually favouring the symbol for Jupiter, and by the mid-1620s he was proscribing a sigil in 1 out of 10 cases. However, the sigil was seldom proscribed in isolation, but in combination with a purge or other medicine. Sometimes the sigil was even immersed in the prescribed medicine so as to impart its power to the potion. Sigils were something that Napier had to be careful with, as the application of images in this way smacked of idolatry for the protestant church, and in fact he went so far as to issue a long defence of their use.

One particular story illustrates the problems he faced with the use of sigils. Napier had proscribed a sigil to a young girl who suffered from fits. The sigil was made as a ring, but a puritan minister convinced the parents to cast it away into a well, where upon the fits returned. The parents found and restored the ring, and the fits stopped, only for the puritan to again convince them to be done with it. This happened repeatedly, until they could not find the ring, and Napier refused to make another as the parents were not willing to trust his medicine.

Alongside sigils and potions, Napier also made use of bloodletting and a selection of strange cures, none more so than a prescription of Pigeon Feet, which quite literally required the patient to cut a pigeon in half and press the bloody halves to the soles of their feet, the theory being that as a pigeon seen landing on a chimney was considered a harbinger of death, so killing and cutting up the bird would harness its power and draw out any bad vapours in the patient’s body. Pigeon poo on the feet was also proscribed, as was making a cake with your own pee to ward off a curse; this was after all still an age when witches and witchcraft was a very real threat to most people. If bitten by a mad dog, the cure was to eat the dog’s liver. It is hard to tell how effective Napier’s prescriptions were, one suspects there may have been something of a placebo effect at play, whereby a strong enough belief in the efficacy of the cure might have had some beneficial effect, especially if dealing with a psychiatric condition or a case of witchcraft, but it is also entirely likely that some of the herbs Napier prescribed were genuinely effective, their benefits having been handed down by successive generations of healers.

The other principal cure offered by Napier were sigils. These were made of metal (often of tin or brass but sometimes silver or gold) and designed to be hung about the neck by a ribbon of taffeta or silk, or they could be worn on a ring or carried in a bag. The sigil would be inscribed with an astronomical symbol and had to be made at the right time and day to imbue them with the maximum potency of the astronomical object they depicted. Equally, the wearer had to use the sigil at the most opportune time as devised by Napier, again so as to maximise the heavenly power of the celestial object. Napier made great use of sigils, usually favouring the symbol for Jupiter, and by the mid-1620s he was proscribing a sigil in 1 out of 10 cases. However, the sigil was seldom proscribed in isolation, but in combination with a purge or other medicine. Sometimes the sigil was even immersed in the prescribed medicine so as to impart its power to the potion. Sigils were something that Napier had to be careful with, as the application of images in this way smacked of idolatry for the protestant church, and in fact he went so far as to issue a long defence of their use.

One particular story illustrates the problems he faced with the use of sigils. Napier had proscribed a sigil to a young girl who suffered from fits. The sigil was made as a ring, but a puritan minister convinced the parents to cast it away into a well, where upon the fits returned. The parents found and restored the ring, and the fits stopped, only for the puritan to again convince them to be done with it. This happened repeatedly, until they could not find the ring, and Napier refused to make another as the parents were not willing to trust his medicine.

Alongside sigils and potions, Napier also made use of bloodletting and a selection of strange cures, none more so than a prescription of Pigeon Feet, which quite literally required the patient to cut a pigeon in half and press the bloody halves to the soles of their feet, the theory being that as a pigeon seen landing on a chimney was considered a harbinger of death, so killing and cutting up the bird would harness its power and draw out any bad vapours in the patient’s body. Pigeon poo on the feet was also proscribed, as was making a cake with your own pee to ward off a curse; this was after all still an age when witches and witchcraft was a very real threat to most people. If bitten by a mad dog, the cure was to eat the dog’s liver. It is hard to tell how effective Napier’s prescriptions were, one suspects there may have been something of a placebo effect at play, whereby a strong enough belief in the efficacy of the cure might have had some beneficial effect, especially if dealing with a psychiatric condition or a case of witchcraft, but it is also entirely likely that some of the herbs Napier prescribed were genuinely effective, their benefits having been handed down by successive generations of healers.

Reputation and legacy

Despite the dangers he faced, by and large Napier’s practice thrived and he was able to avoid the attention and censure of the London medical establishment and the ire of the church, though he must have worried about the snobbery of the medical elite who dismissed country “doctors” as quacks, and vital to the preservation of life and limb had to tread carefully as his methods were bordering on witchcraft. Luckily the patronage of many wealthy patients from the upper echelons of society afforded him some protection, particularly an influential backer named Lord Thomas Wentworth, though in heavily puritan North Buckinghamshire it was easy to make enemies and Napier found himself several times on the wrong side of attacks from the pulpit, notably from the Reverend William Twisse of Newton Longville. Only once was it reported that he was criticised by a parishioner, when in 1616 Napier wrote that, “Goody Kent met me and Master Wallys in the street and called us conjurors.” Robert Wallys was one of the curates that Napier employed to deputise for him and “Goody” was a polite form of address for women, so it is not clear who Goody Kent was or why she had chosen to accost him so, though interestingly Napier was treating a number of “Goody Kents” throughout the early 1600s. Perhaps an unwelcome diagnosis or failure to alleviate an illness had caused some festering resentment to boil over.

Napier’s methods may seem odd and even irrational by today’s standards, but it is reasonable to argue that in his world, he was actually acting in an entirely rational and methodical way, assigning cause and effect and doing his best to catalogue and perfect his knowledge to help his patients. Napier was in common with modern doctors a good listener; he asked his patients careful questions, observed their behaviour, tested in the limited ways available to him their bodily functions, and arrived at a diagnosis and a course of treatment. That he saw upwards of 15 patients per day from all levels of society would indicate that he was generally held in high esteem; he would certainly have been well liked by the poor as it is said he charged little or nothing to minister to them. Unlike Forman, he appears to have been far more scholarly in character, amassing a considerable library of books and becoming well known in intellectual circles. He also achieved what Forman could not, gaining a license to practice medicine in 1604 from Erasamus Webb, archdeacon of Buckingham. He may have been a mage and mystic, but he was also a devout Anglican and might rightly be judged as a bridge between the old world of superstition and the coming age of enlightenment.

Napier died, (allegedly on the very day and hour he had predicted) on April 1st, 1634. He was reputedly on his knees in pray at the time of his death, a position he spent so much time in that his knees were said to have grown horny. The entry in the parish register, likely made by one his curates said, “he dyed praying upon his knees being of great age.” He was 74. Napier passed his estate on to his nephew Sir Richard Napier (son of his brother Robert), who had become his pupil and inherited all his books and papers, though he would have lived at the old medieval manor house located in the grounds of Great Linford Manor Park.

Napier’s methods may seem odd and even irrational by today’s standards, but it is reasonable to argue that in his world, he was actually acting in an entirely rational and methodical way, assigning cause and effect and doing his best to catalogue and perfect his knowledge to help his patients. Napier was in common with modern doctors a good listener; he asked his patients careful questions, observed their behaviour, tested in the limited ways available to him their bodily functions, and arrived at a diagnosis and a course of treatment. That he saw upwards of 15 patients per day from all levels of society would indicate that he was generally held in high esteem; he would certainly have been well liked by the poor as it is said he charged little or nothing to minister to them. Unlike Forman, he appears to have been far more scholarly in character, amassing a considerable library of books and becoming well known in intellectual circles. He also achieved what Forman could not, gaining a license to practice medicine in 1604 from Erasamus Webb, archdeacon of Buckingham. He may have been a mage and mystic, but he was also a devout Anglican and might rightly be judged as a bridge between the old world of superstition and the coming age of enlightenment.

Napier died, (allegedly on the very day and hour he had predicted) on April 1st, 1634. He was reputedly on his knees in pray at the time of his death, a position he spent so much time in that his knees were said to have grown horny. The entry in the parish register, likely made by one his curates said, “he dyed praying upon his knees being of great age.” He was 74. Napier passed his estate on to his nephew Sir Richard Napier (son of his brother Robert), who had become his pupil and inherited all his books and papers, though he would have lived at the old medieval manor house located in the grounds of Great Linford Manor Park.