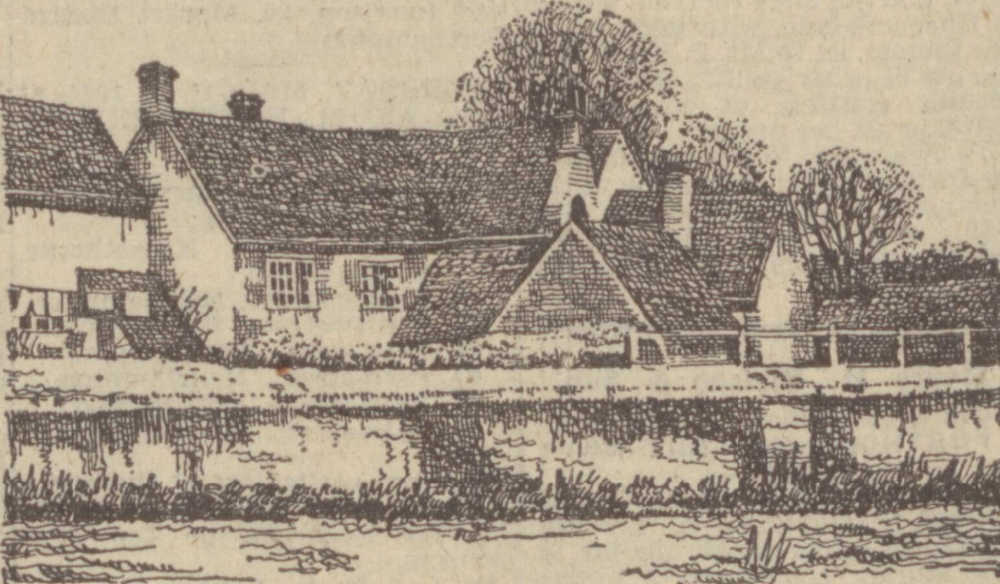

The Black Horse Inn (also known as The Bridge and The Proud Perch), Great Linford

Like the Wharf Inn, also located by the side of the Grand Junction Canal, publicans of The Black Horse Inn would have hoped to capitalise on passing trade from thirsty boatmen and women, however the building may well predate the arrival of the canal in 1800; certainly, there is anecdotal evidence in support of this. A short, illustrated piece in the Northampton Mercury of February 25th, 1944, states that, “a tablet in the gable records that the front part of the inn was built in 1667 and the sashed windows and pedimented doorway supply further evidence of the period.”

This date is considerably contradicted by the brief entry in the book, A Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes (1986, Paul Woodfield, Milton Keynes Development Corporation) which states it to be an "Early 19th century building considerably enlarged in the 20th century."

A bridge to the past and origins of the name

The earliest reference to the building being used as a public house can be found in the county licensing records (Buckinghamshire Archives Q/RLV/1-8) for the Newport Three Hundred, the administrative area in which Great Linford was located. The surprise is that it was not named The Black Horse, but in 1800 was known as The Bridge. The landlord was Thomas Kemp Snr, but we can be sure that the pub sign was changed the following year, as in 1801 The Bridge is gone and it is the same Thomas Kemp who is now listed as the licensee of the Black Horse Inn. There is a possibility that the inn traded under a different sign or signs prior to 1800, but the connections to be drawn with earlier known pub signs The White Horse and The Six Bells are tenuous, though certainly worth exploring. For more information on The White Horse and Six Bells click here.

The pubs brief year long dalliance with the name The Bridge seems simple enough to explain from its proximity to the bridge built to cross the canal, but why the name was changed to The Black Horse, and what this might signify is uncertain. One school of thought is that pubs are named The Black Horse in homage to Black Bess, the infamous steed of the notorious highwayman Dick Turpin, but another theory concerns a jumping black horse that graced the banner of Widukind, the last pagan king of the Old Saxons in Germany. The theory suggests that this symbol was subsequently brought to our shores by ancient invaders. But quite simply, the publican may not have been remotely aware of the sign's purported origins, and merely picked a name that sounded dramatic and appealed to him.

The pubs brief year long dalliance with the name The Bridge seems simple enough to explain from its proximity to the bridge built to cross the canal, but why the name was changed to The Black Horse, and what this might signify is uncertain. One school of thought is that pubs are named The Black Horse in homage to Black Bess, the infamous steed of the notorious highwayman Dick Turpin, but another theory concerns a jumping black horse that graced the banner of Widukind, the last pagan king of the Old Saxons in Germany. The theory suggests that this symbol was subsequently brought to our shores by ancient invaders. But quite simply, the publican may not have been remotely aware of the sign's purported origins, and merely picked a name that sounded dramatic and appealed to him.

A pub or farm, or both?

An important point to consider about the Black Horse Inn is that there is ample evidence that for many years it had a dual function as a working farm, though not to be confused with the Black Horse Farm, a separate farmstead of that name having been subsequently constructed about a mile to the east of the Inn, possibly in the 1870s or very early 1880s. Click here to read about The Black Horse Farm.

Various documents allow us to track the history of land associated with the Black Horse Inn, including two estate maps of 1641 and 1678. As best as can be determined, the inn would come to be built on a field called Morro Leas (also variously called Morral Lees and Morray Leys), in the ownership of the Napier family, who were Lords of the Manor for much of the 1600s. It should be noted that neither map shows a house on this land, but if the existence of the aforementioned tablet dated 1667 is to be believed, only the 1678 map would be expected to show anything, and it is the less detailed of the two. A mortgage document of 1757 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-BAS/41/178) puts the field in the ownership of the Uthwatts (the then Lords of the Manor) and in the occupation of a Philip Ward, whom we know to have been a dairyman and grazier by trade, but again no mention is made of a house or any other sort of dwelling. They were however a family on the up, and you can read more about the Ward family here.

A tithe map of the parish (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) drawn up in 1840 to assign a monetary value to the old and increasingly outdated taxes levied by the church on agricultural production does make explicit mention of an inn, and ascribes to it 161 acres of land across 16 surrounding fields, all of which are named. From this we are able to cross-reference the field names to an indenture (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X 2288) drawn up in 1808 by the Uthwatts. This indenture makes reference to a "messuage tenement or farmhouse with the appurtenances late in the tenure or occupation of Anthony Rowland and now of the said Henry Uthwatt Uthwatt or his tenant." The fields named in the indenture provide several good matches with the 1840 tithe map, so though it seems obvious from the wording of the indenture that Anthony had recently relinquished or had been removed from the tenancy, it does seem that he had been farming at least some of the land later to be associated with the inn, though as will become clear a little later in this history, Anthony was clearly not residing in the building known in future as The Black Horse Inn. The matching fields identified are marked * on the list below.

The indenture shows that Anthony was a significant farmer in the parish, with seven hundred and eighty acres in his tenure. Little else has come to light concerning him, though a will which was proved in 1813 places an Anthony Rowland at Bradwell Wharf, describing him as a victualler and coal dealer; a curious mix of occupations, but that he was a victualler (even though in a different parish) is intriguing. A bundle of documents from the Pelican Life Insurance Company dated 1812-1815 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/27) names Anthony as the former occupant of land and a property in Great Linford, serving as further corroboration of his passing in 1813.

Various documents allow us to track the history of land associated with the Black Horse Inn, including two estate maps of 1641 and 1678. As best as can be determined, the inn would come to be built on a field called Morro Leas (also variously called Morral Lees and Morray Leys), in the ownership of the Napier family, who were Lords of the Manor for much of the 1600s. It should be noted that neither map shows a house on this land, but if the existence of the aforementioned tablet dated 1667 is to be believed, only the 1678 map would be expected to show anything, and it is the less detailed of the two. A mortgage document of 1757 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-BAS/41/178) puts the field in the ownership of the Uthwatts (the then Lords of the Manor) and in the occupation of a Philip Ward, whom we know to have been a dairyman and grazier by trade, but again no mention is made of a house or any other sort of dwelling. They were however a family on the up, and you can read more about the Ward family here.

A tithe map of the parish (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) drawn up in 1840 to assign a monetary value to the old and increasingly outdated taxes levied by the church on agricultural production does make explicit mention of an inn, and ascribes to it 161 acres of land across 16 surrounding fields, all of which are named. From this we are able to cross-reference the field names to an indenture (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X 2288) drawn up in 1808 by the Uthwatts. This indenture makes reference to a "messuage tenement or farmhouse with the appurtenances late in the tenure or occupation of Anthony Rowland and now of the said Henry Uthwatt Uthwatt or his tenant." The fields named in the indenture provide several good matches with the 1840 tithe map, so though it seems obvious from the wording of the indenture that Anthony had recently relinquished or had been removed from the tenancy, it does seem that he had been farming at least some of the land later to be associated with the inn, though as will become clear a little later in this history, Anthony was clearly not residing in the building known in future as The Black Horse Inn. The matching fields identified are marked * on the list below.

The indenture shows that Anthony was a significant farmer in the parish, with seven hundred and eighty acres in his tenure. Little else has come to light concerning him, though a will which was proved in 1813 places an Anthony Rowland at Bradwell Wharf, describing him as a victualler and coal dealer; a curious mix of occupations, but that he was a victualler (even though in a different parish) is intriguing. A bundle of documents from the Pelican Life Insurance Company dated 1812-1815 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/27) names Anthony as the former occupant of land and a property in Great Linford, serving as further corroboration of his passing in 1813.

The Kemps

The same indenture of 1808 mentioned previously contains an entry for Thomas Kemp, naming him as the occupier of The Black Horse Inn, but significantly with no land included, so it does seem clear that the 161 acres associated with the pub in 1840 had not yet been bundled up with the pub in 1808. As to Thomas, we know little of his life in this period, though he appears in local newspapers several times in the early 1800s, such as a notification he placed in the Northampton Mercury of September 4th, 1802, informing readers that he had in his possession a lost “Bay horse”, which could be recovered if its marks could be described, and the cost of its keeping be defrayed. The foot was on the other foot for Thomas in November of 1812, when a “dark grey mare” and “an aged dark brown nag mare” belonging to him were both stolen from a close near the Black Horse. A reward of 15 guineas was offered for their recovery.

As to his other occupation as a farmer, evidence for this is provided by the 1840 tithe map and the 1841 census. The tithe map tells us that the inn now had land assigned to it, and Thomas was farming a mixture of arable and graze lands, plus he had the tenure of two areas of woodland. The tithe map also tells us that the owner of the Inn, homestead and land was the then Lord of the Manor, Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, and the taxable value was £44 and 15 shillings.

The land assigned to the Black Horse Inn runs in a predominantly narrow swath from the north-west corner of the parish where it borders the river Ouse, south to the turnpike road, before crossing the Grand Junction Canal and continuing further south. Running from North to South, the fields were:

#158 - Upper Furness Meadow

#156 - Salt Marsh ?og

#157 - Spinney

#155 - Woad Ground

#154 - Great Meadow

#153 - Little Meadow

#148 - Public House, Homestead and Paddocks

#149 - Northward Church Leys *

#150 - Plantation

#147 - Stone Pit Ashleys

#140 - Plantation - the very small copse of trees to the west of the church yard. *

#141 - Colts Close - which included the present day pond adjacent to the arts centre car-park. *

#146 - Ashleys *

#142 - Cherry Orchard *

#145 - Ashleys Close

#36 - Long Slade

#34 - Great Slade *

As to his other occupation as a farmer, evidence for this is provided by the 1840 tithe map and the 1841 census. The tithe map tells us that the inn now had land assigned to it, and Thomas was farming a mixture of arable and graze lands, plus he had the tenure of two areas of woodland. The tithe map also tells us that the owner of the Inn, homestead and land was the then Lord of the Manor, Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, and the taxable value was £44 and 15 shillings.

The land assigned to the Black Horse Inn runs in a predominantly narrow swath from the north-west corner of the parish where it borders the river Ouse, south to the turnpike road, before crossing the Grand Junction Canal and continuing further south. Running from North to South, the fields were:

#158 - Upper Furness Meadow

#156 - Salt Marsh ?og

#157 - Spinney

#155 - Woad Ground

#154 - Great Meadow

#153 - Little Meadow

#148 - Public House, Homestead and Paddocks

#149 - Northward Church Leys *

#150 - Plantation

#147 - Stone Pit Ashleys

#140 - Plantation - the very small copse of trees to the west of the church yard. *

#141 - Colts Close - which included the present day pond adjacent to the arts centre car-park. *

#146 - Ashleys *

#142 - Cherry Orchard *

#145 - Ashleys Close

#36 - Long Slade

#34 - Great Slade *

The map shows the Inn in red, with outbuildings in grey; the farmstead labelled #148. The matching entry in the accompanying ledger describes this as a “Public House, Homestead and Paddocks”, though the use of the term homestead alongside public house is intriguing. A homestead is generally taken to mean a farmhouse but there is clearly only one dwelling house illustrated. Perhaps it simply means that Inn and Farmhouse were considered one and the same.

We do not know where Thomas Kemp was born, but his year of birth was circa 1774. He married a Jane Hewitt at Great Linford on June 3rd, 1800, and the couple had at least eight children, all born at Great Linford between 1801 and 1821. Thomas was widowed in 1821 and remarried to an Elizabeth Irons in 1823 at Great Linford.

Thomas was described as a farmer rather than an innkeeper on the 1841 census, and also in a notice carried in The Bucks Herald of October 31st that same year, when he was one of a large number of tradespeople who put their name to a petition to change the market day in Newport Pagnell from Saturday to Wednesday.

Most farmers were tenants, as were the Kemps, but they were clearly a family of some means, as further evidenced by the inclusion of both Thomas and his son Thomas Jnr in the 1837 and 1838 poll book entries for the parish. Under an act of parliament passed in 1832, only owners or tenants of property worth £10 or more annually and who had occupied the property for at least a year prior to registering were eligible to vote.

As is also often the case with farmers, Thomas was called upon to undertake other important roles. He was the gamekeeper to the Uthwatts for at least a decade, with repeat notifications of his appointment appearing in newspapers between 1811-1819, and in 1821 he was also appointed as an overseer for the parish. This would have given him responsibility for poor relief, such as money, food and clothing for the destitute in the parish. A particularly illustrative story of his responsibilities appears in the Northampton Mercury of February 10th, 1821, notifying readers that a James Hooton had absconded and left his wife and family chargeable to the parish, and that a handsome reward was offered to anyone who could bring him to Thomas Kemp.

Muddying the waters somewhat, we find Thomas listed on the 1840 tithe map as also occupying the Rectory and its glebe, the latter being 27 acres of grazing and arable land put aside for the use of the parish’s rector, at this time the Reverend Francis Litchfield. This might seem odd, but the Reverend Litchfield was somewhat notoriously an absentee rector, choosing to base himself at his other rectory at Farthinghoe in Northamptonshire and renting the Great Linford rectory out to all and sundry, rather than adopting the traditional approach of providing it as a home for his nominated parish priest.

The tithe map does not provide any certainty as to where the Kemps were residing, but though the 1841 census is equally lacking in specifics, the fact that the enumerator chose to record Thomas Kemp and his family adjacent to The Nags Head is certainly highly suggestive that their primary residence at the time was the next-door Rectory. You can hardly blame Thomas, the Rectory was certainly a swankier address to hang your hat, but it does raise the question, who was living at the Black Horse Inn? But despite this uncertainty, the connection between the Kemps and the Inn appears to have been an enduring one; turning for instance to the Kelly’s trade directory of 1847, we find an entry for Thomas Kemp Senior, describing him as both the proprietor of the Black Horse and a farmer.

Thomas died on December 20th, 1850, and on the next census of 1851 his widow Elizabeth is to be found residing back at the inn, where she is described as a farmer of 155 acres employing seven labourers. With her is her 40-year-old daughter Martha and a servant named Samuel Watson. It seems reasonable to presume she was the pub landlady, a presumption made certain by her entry in the Musson and Craven’s trade directory of 1853. This describes her as a victualler at the Black Horse, and a farmer.

One can only imagine the pandemonium on the night of February 12th, 1859, when a fire was discovered at approximately 9pm. It was a major blaze, with the flames visible at Newport Pagnell and as reported by Croydon’s Weekly Standard of the 19th, ended up consuming seven out-buildings and considerable contents contained within. The full extraordinary account of the drama follows, and it should be noted, makes quite clear that foul play was suspected.

We do not know where Thomas Kemp was born, but his year of birth was circa 1774. He married a Jane Hewitt at Great Linford on June 3rd, 1800, and the couple had at least eight children, all born at Great Linford between 1801 and 1821. Thomas was widowed in 1821 and remarried to an Elizabeth Irons in 1823 at Great Linford.

Thomas was described as a farmer rather than an innkeeper on the 1841 census, and also in a notice carried in The Bucks Herald of October 31st that same year, when he was one of a large number of tradespeople who put their name to a petition to change the market day in Newport Pagnell from Saturday to Wednesday.

Most farmers were tenants, as were the Kemps, but they were clearly a family of some means, as further evidenced by the inclusion of both Thomas and his son Thomas Jnr in the 1837 and 1838 poll book entries for the parish. Under an act of parliament passed in 1832, only owners or tenants of property worth £10 or more annually and who had occupied the property for at least a year prior to registering were eligible to vote.

As is also often the case with farmers, Thomas was called upon to undertake other important roles. He was the gamekeeper to the Uthwatts for at least a decade, with repeat notifications of his appointment appearing in newspapers between 1811-1819, and in 1821 he was also appointed as an overseer for the parish. This would have given him responsibility for poor relief, such as money, food and clothing for the destitute in the parish. A particularly illustrative story of his responsibilities appears in the Northampton Mercury of February 10th, 1821, notifying readers that a James Hooton had absconded and left his wife and family chargeable to the parish, and that a handsome reward was offered to anyone who could bring him to Thomas Kemp.

Muddying the waters somewhat, we find Thomas listed on the 1840 tithe map as also occupying the Rectory and its glebe, the latter being 27 acres of grazing and arable land put aside for the use of the parish’s rector, at this time the Reverend Francis Litchfield. This might seem odd, but the Reverend Litchfield was somewhat notoriously an absentee rector, choosing to base himself at his other rectory at Farthinghoe in Northamptonshire and renting the Great Linford rectory out to all and sundry, rather than adopting the traditional approach of providing it as a home for his nominated parish priest.

The tithe map does not provide any certainty as to where the Kemps were residing, but though the 1841 census is equally lacking in specifics, the fact that the enumerator chose to record Thomas Kemp and his family adjacent to The Nags Head is certainly highly suggestive that their primary residence at the time was the next-door Rectory. You can hardly blame Thomas, the Rectory was certainly a swankier address to hang your hat, but it does raise the question, who was living at the Black Horse Inn? But despite this uncertainty, the connection between the Kemps and the Inn appears to have been an enduring one; turning for instance to the Kelly’s trade directory of 1847, we find an entry for Thomas Kemp Senior, describing him as both the proprietor of the Black Horse and a farmer.

Thomas died on December 20th, 1850, and on the next census of 1851 his widow Elizabeth is to be found residing back at the inn, where she is described as a farmer of 155 acres employing seven labourers. With her is her 40-year-old daughter Martha and a servant named Samuel Watson. It seems reasonable to presume she was the pub landlady, a presumption made certain by her entry in the Musson and Craven’s trade directory of 1853. This describes her as a victualler at the Black Horse, and a farmer.

One can only imagine the pandemonium on the night of February 12th, 1859, when a fire was discovered at approximately 9pm. It was a major blaze, with the flames visible at Newport Pagnell and as reported by Croydon’s Weekly Standard of the 19th, ended up consuming seven out-buildings and considerable contents contained within. The full extraordinary account of the drama follows, and it should be noted, makes quite clear that foul play was suspected.

GREAT LINFORD. Alarming Fire. - About nine o’clock Saturday evening last, a fire broke out the farm premises of Mrs. Kemp, of the Black Horse Inn, Great Linford, which raged with considerable fury until that portion of the premises on fire was nearly consumed. It was first discovered in the straw barn on the side adjoining the towing path of the Grand Junction Canal, but the flames soon spread over the whole of the buildings which were destroyed, being seven in number, containing about 17 1/2 quarters of wheat, barley and beans in sacks, two wagons, winnowing machine, cart, eight sets of harness and various other effects. Fortunately no lives were lost, which undoubted there would, had it not been for the great presence of mind and almost superhuman power of the servant girl (aged only 16 years), who rushed into the yard and was mainly instrumental in saving the lives of four horses, eight beasts, one cow and a donkey, when they were nearly surrounded by the flames. A messenger was dispatched to Newport Pagnell for the fire engine, but not until the fire had been burning some time, yet as the flames had been distinctly seen at Newport, the horses were ordered to be in readiness and the messengers waiting to call the men as soon as the order came, so that only 20 minutes elapsed before they were at the scene of the outbreak with their powerful No. 1 engine, and rendered effective service in extinguishing the burning mass and saving the rest of the premises from destruction. The property (both buildings and stock) was insured in the County Fire Office, There appears to but little doubt that it was the work of an incendiary, the labourers had left the place for three hours, and foot-prints were traced down the embankment of the towing path and back again, just at the spot where the firs broke out.

During the time the fire engine was in work, a man who gave his name William Emerton, of Broughton, wilfully attempted to stop the supply of water through the hose by placing his foot on same, although he had been twice cautioned by the policeman previous. It will be as well to remind those of a mischievous disposition that, such offence might attended with very serious consequences, and the fine inflicted would make it very serious matter either on the pocket or liberty of the offender.

If it was arson, no follow up story can be found as regards an investigation or apprehension of a suspect, though one has to wonder what William Emerton was up to, and if his attempts to impede the fire brigade should have made him the prime suspect. However, though we can identify William as a 21-year-old agricultural labourer in 1859, no motive presents itself, despite his rather suspicious behaviour. The identity of the culprit must therefore go unrecorded, as must also the name of the heroic servant girl who saved so many animals from a fiery end.

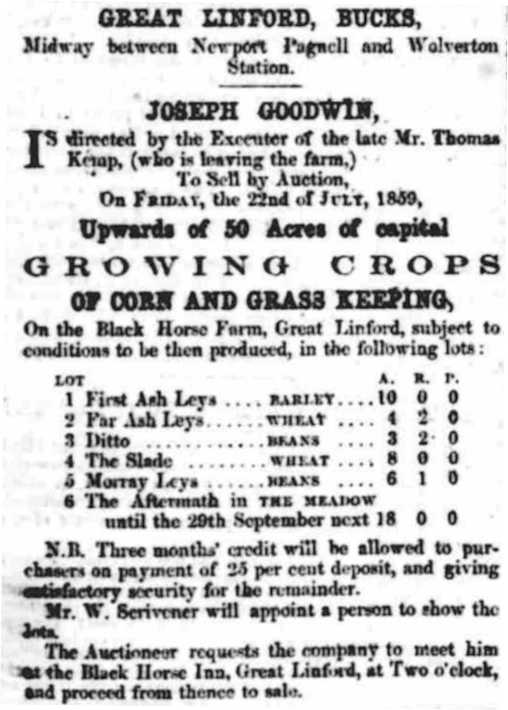

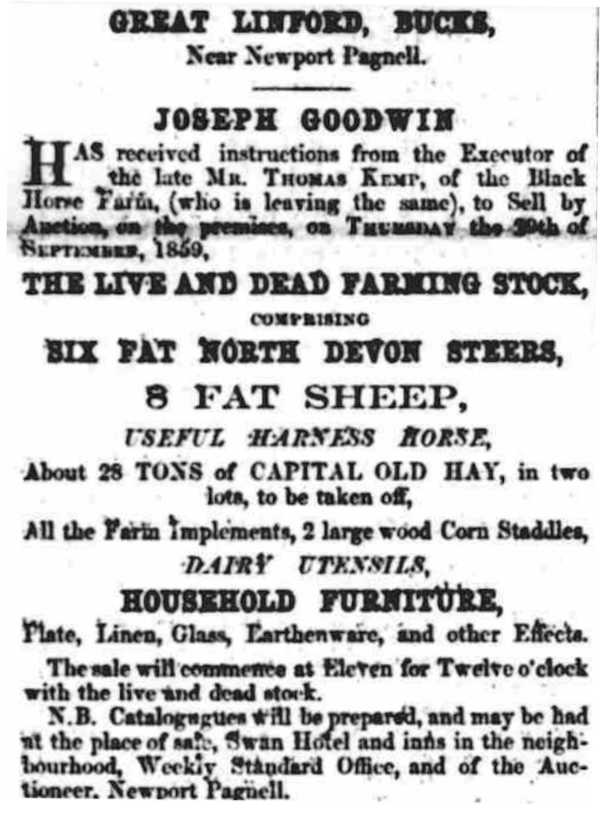

Perhaps the fire proved a fatal blow to Elizabeth, especially if foul play had been involved, as the July 16th, 1859, edition of Croydon's Weekly Standard announced an impending auction on behalf of the executor of the late Mr Thomas Kemp, who was leaving the “Black Horse Farm.” The reference to the Black Horse Farm may simply have been an error or embellishment by the auctioneer or newspaper, especially as interested parties were invited to meet at the inn, but the advertisement does offer the intriguing line, “Mr. W. Scrivener will appoint a person to show the lots." This is likely to be the same William Scrivener named in the 1853 Musson & Craven’s trade directory as a farmer of Great Linford, though the location of his farm has yet to be identified, it is possible that Elizabeth had already left, leaving William to look after her affairs. Of more than passing note, an advertisement carried in the same July 9th edition of the Northampton Mercury offered several fields of growing crops located "near Little Linford Bridge" in the ownership of W. Scrivener, surely the same person.

Perhaps the fire proved a fatal blow to Elizabeth, especially if foul play had been involved, as the July 16th, 1859, edition of Croydon's Weekly Standard announced an impending auction on behalf of the executor of the late Mr Thomas Kemp, who was leaving the “Black Horse Farm.” The reference to the Black Horse Farm may simply have been an error or embellishment by the auctioneer or newspaper, especially as interested parties were invited to meet at the inn, but the advertisement does offer the intriguing line, “Mr. W. Scrivener will appoint a person to show the lots." This is likely to be the same William Scrivener named in the 1853 Musson & Craven’s trade directory as a farmer of Great Linford, though the location of his farm has yet to be identified, it is possible that Elizabeth had already left, leaving William to look after her affairs. Of more than passing note, an advertisement carried in the same July 9th edition of the Northampton Mercury offered several fields of growing crops located "near Little Linford Bridge" in the ownership of W. Scrivener, surely the same person.

The advertisement lists the mix of crops being grown, as well as the field names in use at the time: The Slade, Far Ash Leys, First Ash Lays and Morray Leys. All but the last are close matches to the field names listed on the 1840 tithe map, but significantly, Morray Leys harks back to the 1641 and 1678 estate maps. The very curious sounding “Aftermath in the Meadow" likely refers to a now obsolete farming term for a second mowing; the grass which grows after the first crop of hay in the same season. A meadow was included in the lands occupied by Thomas Kemp in 1840. The disposal of assets continued later in the year, with a sale by auction notice appearing in Croydon's Weekly Standard of September 17th, 1859, which included amongst other lots, "8 fat sheep" and a collection of household furniture.

Again, the Black Horse Farm is referenced, made all the odder because we find not a single reference in 1859 to Elizabeth vacating the inn, which one might imagine to have triggered similar sales notices. Elizabeth passed away at the age of 82 on February 25th, 1860, and was buried in St. Andrew’s churchyard, alongside Thomas and his first wife. However, she had died at Quarry Hall farm, Newport Pagnell, a newspaper notice of her passing observing that she had moved away from The Black Horse Inn, though when is not elaborated upon. There is no sign of a will for Elizabeth, and neither her death nor the fate of the inn or its land appears to have made a splash in the newspapers.

William Warren

The licence of the Black Horse was taken on next by a William Warren. William was born at Great Linford circa 1819, the son of Daniel and Sarah Warren, nee Bird. Daniel was a tailor by trade, and William initially followed in his footsteps, as did another sibling, John. However, by the time of the 1851 census, John and William are at the Wharf Inn public house, with John as the landlord, though William continued for a time to work as a tailor. However, life behind the bar must have had its attractions, as the 1861 census finds William as the publican of the Black Horse Inn. By then he had married a Charlotte Meadows, with the ceremony having taken place at St. Andrews on March 2nd, 1853. The couple had three daughters and a son between 1854 and 1864, Jane, George and Fanny born in Newport Pagnell, and Kate in Great Linford.

One of the earliest references to the Warrens at the Black Horse Inn appears in the Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette of October 9th, 1866. This recounts a frightening encounter by William’s wife Charlotte and their 11-year-old son George, who on the night of Friday 5th were returning from the village to the Inn. But along the way they were set upon by two men, apparently tramps. Twice they pulled Charlotte’s shawl off, but “when she screamed out murder” they fled. The men were duly captured and incarcerated in the lock-up at Newport Pagnell, but in an apparent act of charity, Charlotte declined to prosecute.

On a lighter note, the Northampton Mercury of September 18th, 1867, carries the humorous story of a “monster cabbage”, described as a “very fine red pickling cabbage of the enormous weight of 38Ibs”, which had been grown in the garden of the Black Horse Inn.

We are used today to pubs offering enticing deals on food and drink, but William had grander ideas, advertising in the Bucks Chronicle and Bucks Gazette of December 21st, 1867, that he was offering a “large fat hog” as a prize to members of a pigeon shooting club. As we will see, such events appear to have become traditional at the Black Horse.

Pubs were also places of business for the community, hence in February 1868, we find in Croydon’s Weekly of the 22nd a notice of a forthcoming sale to be held at the pub of a freehold house. This was in the ownership and occupation of a Charles Reynolds, but intriguingly, the house, which was located at an undisclosed location in the village, is described as “well adapted for a public house.” Yet, there is no evidence that a Charles Reynolds ever ran a pub in the village.

As is a common thread with those who resided at the Black Horse Inn, it is sometimes hard to decide if they were farmers first and foremost with a side-line as a publican, or vice-versa. The 1861 census calls William solely an inn keeper, but the Kelly’s trade directories of 1864 and 1869 both state that he was also a grazier, a person who rears or fattens cattle or sheep for market. The 1871 census is at least clear-cut, describing him as a Publican and farmer of 148 acres, very close to the figure of 155 acres that Elizabeth Kemp was farming in 1851. The 1877 Kelly’s directory again places William Warren at the Inn and additionally describes him as a grazier, but by the time of the 1881 census, while still resident at the Inn, he is described only as a farmer.

But despite the rather haphazard way in which William’s tenure was described, it does seem entirely clear that he was always both landlord and farmer. In the latter regard, he was advertising in Croydon's Weekly Standard of February 14th, 1874, for “A good steady man as Milkman. Good wages, and a cottage provided.”

Being a landlord of a pub and farmer offered its fair share of trials and tribulations, such as having to deal with petty thefts. On March 17th, 1876, a James Monrow was apprehended at the Black Horse Inn pilfering a string of onions, value 6p. It reflects sadly on the then prevalent attitudes toward poverty and the harshness of justice, that a man hoping to obtain a few onions to eat was sentenced to 21 days hard labour. On another occasion, “a wretched looking outcast of Newport Pagnell” named Henry Lamley, alias Burk, was discovered in William’s barn. He was there, supposed the Buckingham Express of April 29th, 1871, for an “unlawful purpose”, and was duly sentenced to 21 days hard labour. It seems William was less inclined to offer mercy than had his wife been a decade earlier. There were some particularly gruesome episodes as well, such as a suicide near the Inn in July of 1868, with the body of the victim viewed by the coroner’s jury in one of the Black Horse barns.

On a happier note, on March 13th, 1877, William and Charlotte waved off their youngest daughter Jane to Sunderland with her new husband, John Mitchleson. They had married at St. Andrews, the wedding party having arrived in four carriages with postilions, meaning a person who guides a horse-drawn coach or post chaise while mounted on the horse or one of a pair of horses. After the ceremony the wedding party repaired to the Black Horse, where after a breakfast and toasts, the bride and groom departed for Wolverton Station to begin their journey to their new home.

William was host to an important annual event in late December 1879, when the farmers of the parish were summoned to attend the rent audit of Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt, the then Lord of the Manor. It seems to have been a not unpleasant evening, as aside from a “capital dinner” provided by William, a “return of 15 percent was given back to the tenants.”

The Warren family, William, Charlotte and daughters Frances and Kate are present at the Black Horse Inn on the 1881 census (plus two servants), but that same year William placed a notice in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 27th notifying the public of his intention to vacate, with a detailed list of items for sale. Notably, this was a sale of agricultural equipment and livestock, certain proof that he was running a farming enterprise from the Black Horse Inn. Another ad in the same newspaper of September 24th announced the disposal of household furniture from the Inn. The notice of the sale of farm equipment did place the sale at “The Blackhorse Farm”, but if this refers to the land around the Inn, or the newer Black Horse Farm that had been constructed by this time, we are never likely to be sure.

William passed away on June 20th, 1882, and is buried in St. Andrew’s churchyard. As a final incongruity to this part of the story, he is described in his probate record as a brewer. His widow Charlotte then moved to the parish of Stantonbury, where she herself earned a living as a brewer, though given that pubs often brewed their own beer, it is is not necessarily so odd to imagine that the couple had acquired the skill. By the 1901 census Charlotte was living at Stantonbury Wharf in the household of her married daughter Kate. She passed away at number 42, Stratford Road, Wolverton, on December 19th, 1905.

One of the earliest references to the Warrens at the Black Horse Inn appears in the Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette of October 9th, 1866. This recounts a frightening encounter by William’s wife Charlotte and their 11-year-old son George, who on the night of Friday 5th were returning from the village to the Inn. But along the way they were set upon by two men, apparently tramps. Twice they pulled Charlotte’s shawl off, but “when she screamed out murder” they fled. The men were duly captured and incarcerated in the lock-up at Newport Pagnell, but in an apparent act of charity, Charlotte declined to prosecute.

On a lighter note, the Northampton Mercury of September 18th, 1867, carries the humorous story of a “monster cabbage”, described as a “very fine red pickling cabbage of the enormous weight of 38Ibs”, which had been grown in the garden of the Black Horse Inn.

We are used today to pubs offering enticing deals on food and drink, but William had grander ideas, advertising in the Bucks Chronicle and Bucks Gazette of December 21st, 1867, that he was offering a “large fat hog” as a prize to members of a pigeon shooting club. As we will see, such events appear to have become traditional at the Black Horse.

Pubs were also places of business for the community, hence in February 1868, we find in Croydon’s Weekly of the 22nd a notice of a forthcoming sale to be held at the pub of a freehold house. This was in the ownership and occupation of a Charles Reynolds, but intriguingly, the house, which was located at an undisclosed location in the village, is described as “well adapted for a public house.” Yet, there is no evidence that a Charles Reynolds ever ran a pub in the village.

As is a common thread with those who resided at the Black Horse Inn, it is sometimes hard to decide if they were farmers first and foremost with a side-line as a publican, or vice-versa. The 1861 census calls William solely an inn keeper, but the Kelly’s trade directories of 1864 and 1869 both state that he was also a grazier, a person who rears or fattens cattle or sheep for market. The 1871 census is at least clear-cut, describing him as a Publican and farmer of 148 acres, very close to the figure of 155 acres that Elizabeth Kemp was farming in 1851. The 1877 Kelly’s directory again places William Warren at the Inn and additionally describes him as a grazier, but by the time of the 1881 census, while still resident at the Inn, he is described only as a farmer.

But despite the rather haphazard way in which William’s tenure was described, it does seem entirely clear that he was always both landlord and farmer. In the latter regard, he was advertising in Croydon's Weekly Standard of February 14th, 1874, for “A good steady man as Milkman. Good wages, and a cottage provided.”

Being a landlord of a pub and farmer offered its fair share of trials and tribulations, such as having to deal with petty thefts. On March 17th, 1876, a James Monrow was apprehended at the Black Horse Inn pilfering a string of onions, value 6p. It reflects sadly on the then prevalent attitudes toward poverty and the harshness of justice, that a man hoping to obtain a few onions to eat was sentenced to 21 days hard labour. On another occasion, “a wretched looking outcast of Newport Pagnell” named Henry Lamley, alias Burk, was discovered in William’s barn. He was there, supposed the Buckingham Express of April 29th, 1871, for an “unlawful purpose”, and was duly sentenced to 21 days hard labour. It seems William was less inclined to offer mercy than had his wife been a decade earlier. There were some particularly gruesome episodes as well, such as a suicide near the Inn in July of 1868, with the body of the victim viewed by the coroner’s jury in one of the Black Horse barns.

On a happier note, on March 13th, 1877, William and Charlotte waved off their youngest daughter Jane to Sunderland with her new husband, John Mitchleson. They had married at St. Andrews, the wedding party having arrived in four carriages with postilions, meaning a person who guides a horse-drawn coach or post chaise while mounted on the horse or one of a pair of horses. After the ceremony the wedding party repaired to the Black Horse, where after a breakfast and toasts, the bride and groom departed for Wolverton Station to begin their journey to their new home.

William was host to an important annual event in late December 1879, when the farmers of the parish were summoned to attend the rent audit of Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt, the then Lord of the Manor. It seems to have been a not unpleasant evening, as aside from a “capital dinner” provided by William, a “return of 15 percent was given back to the tenants.”

The Warren family, William, Charlotte and daughters Frances and Kate are present at the Black Horse Inn on the 1881 census (plus two servants), but that same year William placed a notice in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 27th notifying the public of his intention to vacate, with a detailed list of items for sale. Notably, this was a sale of agricultural equipment and livestock, certain proof that he was running a farming enterprise from the Black Horse Inn. Another ad in the same newspaper of September 24th announced the disposal of household furniture from the Inn. The notice of the sale of farm equipment did place the sale at “The Blackhorse Farm”, but if this refers to the land around the Inn, or the newer Black Horse Farm that had been constructed by this time, we are never likely to be sure.

William passed away on June 20th, 1882, and is buried in St. Andrew’s churchyard. As a final incongruity to this part of the story, he is described in his probate record as a brewer. His widow Charlotte then moved to the parish of Stantonbury, where she herself earned a living as a brewer, though given that pubs often brewed their own beer, it is is not necessarily so odd to imagine that the couple had acquired the skill. By the 1901 census Charlotte was living at Stantonbury Wharf in the household of her married daughter Kate. She passed away at number 42, Stratford Road, Wolverton, on December 19th, 1905.

William Gaskins

The next landlord we can identify is a William Gaskins, with the earliest reference to his tenancy appearing in the Kelly’s trade directory of 1883. William had been born in Haversham in 1844 and became a carpenter by trade. He married Sarah Ann Brain (born Drybrook in Gloucester) at Haversham on September 25th, 1865, and they had five children together between 1868 to 1877, all born at Haversham. William appears to have had no interest in farming, but he had plenty of other strings to his bow, appearing in the 1887 Kelly’s directory as a publican and a builder, but this was not the end of his talents, with butcher added to his repertoire of trades on the 1891 census. Anything then but a farmer. Meanwhile, two of his sons had become carpenters, another was a butcher, and his daughter Hannah was a dressmaker’s apprentice.

This does seem to point toward the cessation of farming at the Black Horse Inn, and indeed in this same period, we find references to the “Black Horse Farm” rising in prominence, which we can assume to be new farmstead built further along the Newport Road. However, as we will see later in this history, we do have several further references to farming at the Inn, so matters are not yet entirely certain.

Owning a pub inevitably brought the landlord into contact with those for whom drink loosened inhibitions, and there are several cases of violence breaking out. One such altercation broke out on the evening of November 10th, 1883, as reported upon by the Bucks Herald of November 17th. George Warwick was accused of striking William Croft with his fist, and then biting his victim! The brawl had broken out as Croft had reported Warwick over an undisclosed matter at Wolverton Railway Works, where both men were employed. This was their first encounter since the complaint, and passions had clearly boiled over. Warwick had brought a counter-claim against Croft in the same magistrate’s session, but as witnesses for both men gave conflicting accounts of the fight, both cases were dismissed.

Less lucky was Alfred Wein, who on June 3rd, 1884, was charged with willfully damaging property at the Black Horse Inn. Testimony was provided in court by Sarah Gaskins, who explained that the defendant had had one pint of beer, but then became very disorderly when she refused to serve him another. Wein then went on something of a rampage, breaking several pint jugs, two glasses and a cup and saucer. On being ejected from the pub, he threw three bricks through a rear window as well as damaging the door. For want of a second pint, he was fined £1, plus 15 shillings damages, or if unable to pay, one month in prison.

The tradition of a Christmas pigeon shoot at the pub seems to have been continued by William Gaskins, with the announcement in Croydon's Weekly Standard of December 19th, 1885, that he was arranging a Boxing Day shoot, with a “Fat Pig” as a prize. That this was a regular event is confirmed by another ad he placed in Croydon's Weekly Standard of December 14th, 1889, headlined “Annual pigeon shooting.” This time a pony valued at £20 was offered as the star prize, but with a runner’s up prize of a “Fat Pig, valued £4.” The unfortunate pigeons were to be supplied by a Mr C. Bull of Wolverton.

William sounds like someone who could see a good opportunity, as in May of 1888, he provided the refreshments to the spectators of “Pony and Galloway” races held at Newport Pagnell; the Galloway is a breed of horse now considered to be extinct. Up to 3000 persons attended the races, so we can presume William must have had a very successful day’s business.

Another coroner’s inquiry that took place at the Black Horse in 1889 concerned the death of a Jesse Gaskins, who died in horrific circumstances when he slipped from a cart and was dragged to his death by a runaway horse. The accident happened close to the Black Horse, and given his surname, it raises the intriguing question, was Jesse a relation of William Gaskins? No such intimation is made in the newspaper accounts of the inquiry and given that Jesse was not employed at the Black Horse, this may not be so surprising. However, that Jesse seems to have been born in Haversham, as was William, is highly suggestive of a family connection.

Thanks to an attentive canal barge boatman, a near calamity was luckily averted on the evening of Saturday January 25th, 1890, when a fire broke out at the Inn. It was reported by the Buckingham Express of February 1st that the boatman had raised the alarm in time, and with plentiful water on hand from the canal to quench the flames, matters were brought under control by the prompt actions of those in the pub. The source of the fire was traced to an over-heating flue, and though over £100 of damage was caused including the loss of one room and a quantity of hops, the Gaskins had had the foresight to arrange insurance. The presence of hops offers the first clue that the pub was brewing its own beer.

We can connect another grim story to the pub, as recounted in the Bicester Herald of November 6th, 1891. It concerns the suicide of an unemployed Bradwell man named Samuel Teagle. When last seen, he had begged the price of a pint from the last man to see him alive, and it seems from the evidence presented that he had supped his last beer at the Black Horse, before drowning himself in the river Ouse.

William Gaskins remained as publican until the middle of 1895, when a number of sale notices appeared in local newspapers to announce his departure. One advertisement in particular provides an answer to an important question, where was the Black Horse getting its beer? The answer is that for William at least, he was brewing his own. The ad, which appears in Croydon's Weekly Standard of May 25th, 1895, seems to imply a significant enterprise, describing the items for sale as, “The whole of the brewing plant, consisting of mash tub, coolers, fermenting vat, under vat, 120-gallon copper, copper pump and 9 two-and-a-half hogshead, and 2 ten-hogshead.”

A hogshead is a cask for storing alcohol, which came in a variety of sizes. Remembering that Willian was also a builder and his sons carpenters, we find additionally listed for sale a part finished timber carriage, a variety of carts, timber and sundry ladders, and most intriguingly, a railway coach. Additionally, he was disposing of a pregnant sow and a brawn, the latter being the meat from a pig’s or calf’s head that has been preserved in jelly, in a pot.

Arguably the Gaskins left the village under something of a pall, as on August 21st, 1895, Sidney Gaskins, William’s son, was charged in his absence with not one, but two assaults at Great Linford. Appearing in the witness box with a “lovely black eye”, James Fowler laid the blame on Sidney, with a William Fennimore following the first witness into the box, to also accuse Sidney of assault. No doubt hindered by his failure to appear in court, Sidney was fined 10 shillings plus costs in both cases.

This does seem to point toward the cessation of farming at the Black Horse Inn, and indeed in this same period, we find references to the “Black Horse Farm” rising in prominence, which we can assume to be new farmstead built further along the Newport Road. However, as we will see later in this history, we do have several further references to farming at the Inn, so matters are not yet entirely certain.

Owning a pub inevitably brought the landlord into contact with those for whom drink loosened inhibitions, and there are several cases of violence breaking out. One such altercation broke out on the evening of November 10th, 1883, as reported upon by the Bucks Herald of November 17th. George Warwick was accused of striking William Croft with his fist, and then biting his victim! The brawl had broken out as Croft had reported Warwick over an undisclosed matter at Wolverton Railway Works, where both men were employed. This was their first encounter since the complaint, and passions had clearly boiled over. Warwick had brought a counter-claim against Croft in the same magistrate’s session, but as witnesses for both men gave conflicting accounts of the fight, both cases were dismissed.

Less lucky was Alfred Wein, who on June 3rd, 1884, was charged with willfully damaging property at the Black Horse Inn. Testimony was provided in court by Sarah Gaskins, who explained that the defendant had had one pint of beer, but then became very disorderly when she refused to serve him another. Wein then went on something of a rampage, breaking several pint jugs, two glasses and a cup and saucer. On being ejected from the pub, he threw three bricks through a rear window as well as damaging the door. For want of a second pint, he was fined £1, plus 15 shillings damages, or if unable to pay, one month in prison.

The tradition of a Christmas pigeon shoot at the pub seems to have been continued by William Gaskins, with the announcement in Croydon's Weekly Standard of December 19th, 1885, that he was arranging a Boxing Day shoot, with a “Fat Pig” as a prize. That this was a regular event is confirmed by another ad he placed in Croydon's Weekly Standard of December 14th, 1889, headlined “Annual pigeon shooting.” This time a pony valued at £20 was offered as the star prize, but with a runner’s up prize of a “Fat Pig, valued £4.” The unfortunate pigeons were to be supplied by a Mr C. Bull of Wolverton.

William sounds like someone who could see a good opportunity, as in May of 1888, he provided the refreshments to the spectators of “Pony and Galloway” races held at Newport Pagnell; the Galloway is a breed of horse now considered to be extinct. Up to 3000 persons attended the races, so we can presume William must have had a very successful day’s business.

Another coroner’s inquiry that took place at the Black Horse in 1889 concerned the death of a Jesse Gaskins, who died in horrific circumstances when he slipped from a cart and was dragged to his death by a runaway horse. The accident happened close to the Black Horse, and given his surname, it raises the intriguing question, was Jesse a relation of William Gaskins? No such intimation is made in the newspaper accounts of the inquiry and given that Jesse was not employed at the Black Horse, this may not be so surprising. However, that Jesse seems to have been born in Haversham, as was William, is highly suggestive of a family connection.

Thanks to an attentive canal barge boatman, a near calamity was luckily averted on the evening of Saturday January 25th, 1890, when a fire broke out at the Inn. It was reported by the Buckingham Express of February 1st that the boatman had raised the alarm in time, and with plentiful water on hand from the canal to quench the flames, matters were brought under control by the prompt actions of those in the pub. The source of the fire was traced to an over-heating flue, and though over £100 of damage was caused including the loss of one room and a quantity of hops, the Gaskins had had the foresight to arrange insurance. The presence of hops offers the first clue that the pub was brewing its own beer.

We can connect another grim story to the pub, as recounted in the Bicester Herald of November 6th, 1891. It concerns the suicide of an unemployed Bradwell man named Samuel Teagle. When last seen, he had begged the price of a pint from the last man to see him alive, and it seems from the evidence presented that he had supped his last beer at the Black Horse, before drowning himself in the river Ouse.

William Gaskins remained as publican until the middle of 1895, when a number of sale notices appeared in local newspapers to announce his departure. One advertisement in particular provides an answer to an important question, where was the Black Horse getting its beer? The answer is that for William at least, he was brewing his own. The ad, which appears in Croydon's Weekly Standard of May 25th, 1895, seems to imply a significant enterprise, describing the items for sale as, “The whole of the brewing plant, consisting of mash tub, coolers, fermenting vat, under vat, 120-gallon copper, copper pump and 9 two-and-a-half hogshead, and 2 ten-hogshead.”

A hogshead is a cask for storing alcohol, which came in a variety of sizes. Remembering that Willian was also a builder and his sons carpenters, we find additionally listed for sale a part finished timber carriage, a variety of carts, timber and sundry ladders, and most intriguingly, a railway coach. Additionally, he was disposing of a pregnant sow and a brawn, the latter being the meat from a pig’s or calf’s head that has been preserved in jelly, in a pot.

Arguably the Gaskins left the village under something of a pall, as on August 21st, 1895, Sidney Gaskins, William’s son, was charged in his absence with not one, but two assaults at Great Linford. Appearing in the witness box with a “lovely black eye”, James Fowler laid the blame on Sidney, with a William Fennimore following the first witness into the box, to also accuse Sidney of assault. No doubt hindered by his failure to appear in court, Sidney was fined 10 shillings plus costs in both cases.

A high turnover of landlords

The license of the Black Horse was next transferred to a William Warwick. While we have no direct records of his tenure other than the newspaper notice of his taking up the license, it seems plausible to suppose that this was the William Warwick born at Great Linford in 1846, and whom we find as landlord of the Chequer’s Inn at Leckhampstead on the 1891 census.

There is a rapid turnover of landlords in this period. Samuel Gale gamely tried to rustle up some custom in August of 1896, placing a notice in Croydon's Weekly Standard of the 1st, that he would he hosting a Quoit Handicap on the 3rd, at which he hoped to see all his customers and friends. Prizes included ducks and geese, lunch at a nominal charge and “Higgins and Co.’s Ales and Stout in splendid condition.” He also added that games would be played on a new quoit ground. In September the same year, he applied to the magistrates for an extension to his opening hours on the occasion of a “harvest supper”, but it was deemed he was charging too much per head, and the request was denied.

Unfortunately, Samuel’s laudable efforts seem to have come to nothing, as Croydon's Weekly Standard of October 17th, 1896, reports that the license of the Black Horse had been transferred from him to a Frank Higgins, interestingly described as a brewer. The Black Horse was up for Let again in 1897 (Northampton Mercury, July 30th) for immediate possession, so presumably vacated in haste. The brief advertisement does give us a glimpse into the layout of the property, telling us that it came with 12 acres of superior grassland (confirming that the Inn had by now lost much of its land) and two large well stocked gardens. The Northampton Mercury of October 1st, 1897, reported that the license had been taken over by a John Bodle, but this was another fleeting tenancy, as in due course we find a Thomas Henry Jones as the new publican.

Thomas was involved in a complex case pertaining to poaching, which if nothing else, demonstrates the proprietary lengths to which the Uthwatts of Great Linford Manor were willing to go in order to demonstrate their control over their land and its resources. The account of the case, carried in great detail in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 20th, 1898, can be summed up as follows. Driving past the Black Horse on the evening of July 28th, William and Gerard Uthwatt spied a man later identified as Albert Umney leaning on a gate looking toward a spinney, a wooded area. Albert was carrying a loaded and cocked shotgun, and upon being challenged, admitted to have been waiting for a rabbit to appear. Asked upon what authority he was hunting, he replied that he had the verbal but not written permission of the landlord of the Black Horse Inn.

This was disputed by the Uthwatts, who stated in court that the spinney in question was not part of the tenancy of the Black Horse, and furthermore no tenant of the pub had ever enjoyed shooting rights in the spinney. Questioned on the matter by the bench, Thomas Jones testified that he had invited Umney to shoot as a friend and had left him momentarily to return to the Inn to write out a written note of permission.

A conviction hinged on whether Umeny had essentially been waiting innocently leaning against a gate looking toward the spinney or had been intending to shoot a rabbit within the Spinney. Arguments were made that for the purposes of the Game Act, the highway adjacent to the land in question was the property of the landowner, and after deliberation the magistrates agreed that a trespass had occurred, though of a minor nature. A fine of six pence was imposed, with 11 shillings costs.

Albert Umney was not however about to let the matter end there and had countersued Gerard Uthwatt for assault. Gerard had confiscated Umney’s shotgun, with the court informed that he had been appointed parish constable for Great Linford, and therefore had every right to do so, but Umney’s counsel argued that had a struggle ensued, the consequences could have been very serious to life and limb. It appears the magistrates were inclined to agree, and fined Gerard six pence with 11 shillings costs. That it was the exact same amount as imposed in the previous case seems more than coincidental.

Perhaps the case did not endear Thomas to the Uthwatts, as by the time of the 1899 Kelly’s trade directory, he had made way for a Joseph Davies, who was then swiftly replaced by a John Kelly, who in November of 1900, was renting out the “Black Horse Fields” for the purpose of grazing cattle or horses. Kelly was himself rapidly replaced by several more landlords in quick succession, who fared little better in terms of the lengths of their tenures but do provide some interesting stories.

There is a rapid turnover of landlords in this period. Samuel Gale gamely tried to rustle up some custom in August of 1896, placing a notice in Croydon's Weekly Standard of the 1st, that he would he hosting a Quoit Handicap on the 3rd, at which he hoped to see all his customers and friends. Prizes included ducks and geese, lunch at a nominal charge and “Higgins and Co.’s Ales and Stout in splendid condition.” He also added that games would be played on a new quoit ground. In September the same year, he applied to the magistrates for an extension to his opening hours on the occasion of a “harvest supper”, but it was deemed he was charging too much per head, and the request was denied.

Unfortunately, Samuel’s laudable efforts seem to have come to nothing, as Croydon's Weekly Standard of October 17th, 1896, reports that the license of the Black Horse had been transferred from him to a Frank Higgins, interestingly described as a brewer. The Black Horse was up for Let again in 1897 (Northampton Mercury, July 30th) for immediate possession, so presumably vacated in haste. The brief advertisement does give us a glimpse into the layout of the property, telling us that it came with 12 acres of superior grassland (confirming that the Inn had by now lost much of its land) and two large well stocked gardens. The Northampton Mercury of October 1st, 1897, reported that the license had been taken over by a John Bodle, but this was another fleeting tenancy, as in due course we find a Thomas Henry Jones as the new publican.

Thomas was involved in a complex case pertaining to poaching, which if nothing else, demonstrates the proprietary lengths to which the Uthwatts of Great Linford Manor were willing to go in order to demonstrate their control over their land and its resources. The account of the case, carried in great detail in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 20th, 1898, can be summed up as follows. Driving past the Black Horse on the evening of July 28th, William and Gerard Uthwatt spied a man later identified as Albert Umney leaning on a gate looking toward a spinney, a wooded area. Albert was carrying a loaded and cocked shotgun, and upon being challenged, admitted to have been waiting for a rabbit to appear. Asked upon what authority he was hunting, he replied that he had the verbal but not written permission of the landlord of the Black Horse Inn.

This was disputed by the Uthwatts, who stated in court that the spinney in question was not part of the tenancy of the Black Horse, and furthermore no tenant of the pub had ever enjoyed shooting rights in the spinney. Questioned on the matter by the bench, Thomas Jones testified that he had invited Umney to shoot as a friend and had left him momentarily to return to the Inn to write out a written note of permission.

A conviction hinged on whether Umeny had essentially been waiting innocently leaning against a gate looking toward the spinney or had been intending to shoot a rabbit within the Spinney. Arguments were made that for the purposes of the Game Act, the highway adjacent to the land in question was the property of the landowner, and after deliberation the magistrates agreed that a trespass had occurred, though of a minor nature. A fine of six pence was imposed, with 11 shillings costs.

Albert Umney was not however about to let the matter end there and had countersued Gerard Uthwatt for assault. Gerard had confiscated Umney’s shotgun, with the court informed that he had been appointed parish constable for Great Linford, and therefore had every right to do so, but Umney’s counsel argued that had a struggle ensued, the consequences could have been very serious to life and limb. It appears the magistrates were inclined to agree, and fined Gerard six pence with 11 shillings costs. That it was the exact same amount as imposed in the previous case seems more than coincidental.

Perhaps the case did not endear Thomas to the Uthwatts, as by the time of the 1899 Kelly’s trade directory, he had made way for a Joseph Davies, who was then swiftly replaced by a John Kelly, who in November of 1900, was renting out the “Black Horse Fields” for the purpose of grazing cattle or horses. Kelly was himself rapidly replaced by several more landlords in quick succession, who fared little better in terms of the lengths of their tenures but do provide some interesting stories.

Frederick Proctor Malacky

Frederick Proctor Malacky was a London born engineer by trade, and in March of 1901 he had taken over the licence from John Kelly. Frederick is to be found on the 1901 census at The Black Horse alongside his wife Anna Maria, nee Watts, their two sons, and a boarder named Osbourn Lock Vinson. One of Frederick’s sons, also named Frederick, is listed on the census as a cycle maker, and 15-year-old Osbourn is a cycle maker’s apprentice. The 1901 census was conducted March 31st, so either things were going well for the business necessitating more help, or Osbourn had left Frederick’s employ by April 27th the same year, as on that day Croydon's Weekly Standard carried a help wanted ad for, “A boy to learn Cycle and Engineering work.”

Frederick was indeed running a business from the pub engaged in the buying and selling of bicycles and other sundry items, as evidenced by the ads he placed in local newspapers such as one published in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 17th, 1901, which offered “a quantity of New and Second-hand bicycles for sale, cheap. Must be sold. Also mail carts, perambulators and bath chairs.” He was also renting out bikes by the day, week or hour.

A tale of bicycle theft appears in Croydon's Weekly Standard of September 21st, 1901, and though Frederick Malacky was not charged for any part in the attempted commission of this fraudulent transaction, the account of the trial is interesting. The case was that John Clare of no fixed abode had a few weeks earlier stolen an unattended bicycle from the Northamptonshire village of Harpole and was then observed by police inspector Anthony at the Black Horse on the evening of the 7th. Presumably not having recognised the inspector, who was in plain clothes, Frederick had said, “Here’s a good bicycle for sale”, and upon the inspector inquiring who had it for sale, Clare said I have, and requested £4, 10 shillings for the bike. To this, Frederick retorted, “Why, you offered me it for 30 shillings.”

The account of the trial makes no observation on the curious nature of this conversation, but a suspicious mind would perhaps presume some collusion between Frederick and the thief. After questioning by the inspector, and with no proof offered for Clare’s legal possession of the bike, he was taken into custody and confessed to the theft the next morning.

Frederick appears in another particularly intriguing story concerning his tenure at the Black Horse, which is worth relating here as it pertains to one of the more curious aspects of English licensing laws at the time, specifically as regards the strict conditions that then existed for Sunday trading, which placed limits on who could drink in pubs. There was however an exception for so called legitimate travellers, persons who were passing through and therefore could partake of a pint during the hours otherwise denied to locals. Clearly this was open to abuse, and that is exactly what we find in the account offered in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of August 3rd, 1901.

Unfortunately for the two men brought before the court, a Sergeant Gascoigne of Stony Stratford had been in the pub on the evening of July 14th, having business with the landlord. While there he had observed a Bert Lloyd and George Coleman enter the pub, where upon both claimed to be travellers. Frederick clearly knew the rules and was being scrupulous with a member of the constabulary in attendance, as he made sure to challenge the men, as did his daughter, but both were rumbled and revealed to be from Bradwell where they were employed at the sewage works. It was observed in court that to be served legally, they must have come at least three miles, and “must not go out for a walk just to get a drink.” Since they were labouring men, the court was inclined to be lenient, and fined both seven shillings, six pence each, plus nine shillings costs.

Frederick was not having a good year, as in October he was back in court, accused of failing to pay the poor rate, but perhaps he had other things on his mind. Sadly, Frederick and Anna’s marriage was on rocky ground, such that it was cited as an impediment to his application for the renewal of his publican’s license. Anna filed for a separation in July of 1901, but by September the objections were withdrawn on the rather misogynistic sounding note, that the landlord had, “had a lot of trouble with his wife.” It was however also noted that he was under notice to quit. As an odd little postscript to the story, Frederick and Anna must have patched things up, as in 1906 they were both charged (though acquitted) with receiving stolen goods in Northampton, which perhaps casts the previous story concerning the stolen bike in a fresh light.

Frederick was indeed running a business from the pub engaged in the buying and selling of bicycles and other sundry items, as evidenced by the ads he placed in local newspapers such as one published in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 17th, 1901, which offered “a quantity of New and Second-hand bicycles for sale, cheap. Must be sold. Also mail carts, perambulators and bath chairs.” He was also renting out bikes by the day, week or hour.

A tale of bicycle theft appears in Croydon's Weekly Standard of September 21st, 1901, and though Frederick Malacky was not charged for any part in the attempted commission of this fraudulent transaction, the account of the trial is interesting. The case was that John Clare of no fixed abode had a few weeks earlier stolen an unattended bicycle from the Northamptonshire village of Harpole and was then observed by police inspector Anthony at the Black Horse on the evening of the 7th. Presumably not having recognised the inspector, who was in plain clothes, Frederick had said, “Here’s a good bicycle for sale”, and upon the inspector inquiring who had it for sale, Clare said I have, and requested £4, 10 shillings for the bike. To this, Frederick retorted, “Why, you offered me it for 30 shillings.”

The account of the trial makes no observation on the curious nature of this conversation, but a suspicious mind would perhaps presume some collusion between Frederick and the thief. After questioning by the inspector, and with no proof offered for Clare’s legal possession of the bike, he was taken into custody and confessed to the theft the next morning.

Frederick appears in another particularly intriguing story concerning his tenure at the Black Horse, which is worth relating here as it pertains to one of the more curious aspects of English licensing laws at the time, specifically as regards the strict conditions that then existed for Sunday trading, which placed limits on who could drink in pubs. There was however an exception for so called legitimate travellers, persons who were passing through and therefore could partake of a pint during the hours otherwise denied to locals. Clearly this was open to abuse, and that is exactly what we find in the account offered in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of August 3rd, 1901.

Unfortunately for the two men brought before the court, a Sergeant Gascoigne of Stony Stratford had been in the pub on the evening of July 14th, having business with the landlord. While there he had observed a Bert Lloyd and George Coleman enter the pub, where upon both claimed to be travellers. Frederick clearly knew the rules and was being scrupulous with a member of the constabulary in attendance, as he made sure to challenge the men, as did his daughter, but both were rumbled and revealed to be from Bradwell where they were employed at the sewage works. It was observed in court that to be served legally, they must have come at least three miles, and “must not go out for a walk just to get a drink.” Since they were labouring men, the court was inclined to be lenient, and fined both seven shillings, six pence each, plus nine shillings costs.

Frederick was not having a good year, as in October he was back in court, accused of failing to pay the poor rate, but perhaps he had other things on his mind. Sadly, Frederick and Anna’s marriage was on rocky ground, such that it was cited as an impediment to his application for the renewal of his publican’s license. Anna filed for a separation in July of 1901, but by September the objections were withdrawn on the rather misogynistic sounding note, that the landlord had, “had a lot of trouble with his wife.” It was however also noted that he was under notice to quit. As an odd little postscript to the story, Frederick and Anna must have patched things up, as in 1906 they were both charged (though acquitted) with receiving stolen goods in Northampton, which perhaps casts the previous story concerning the stolen bike in a fresh light.

Harry Ware

Frederick was succeeded by an Alfred Paybody in January of 1902, swiftly followed in November the same year by one of the more colourful characters to be associated with the Black Horse. Harry Ware was a quite well-known boxer, who in 1902 had announced in the sporting press that he was retiring from the ring to concentrate on running the Black Horse Inn. He went on however to set up a training gym on the premises, which was lauded for its superb facilities, but tragedy was to strike when a neighbour’s child under the care of Harry’s wife accidentally drowned in the canal. For the full story of Harry Ware at the Black Horse, click here.

Philip Lang Middleweek

Harry Ware gave up the Black Horse sometime around 1904, and it is not entirely certain who immediately followed, but a Philip Middleweek is listed as the landlord in Kelly’s trade directory of 1907, which coincides with the earliest mention of the name in the local press, when he applied to the sanitary committee for permission to be a milk seller, the first time in many years that we have evidence of a landlord of the Black Horse Inn engaging in any kind of farming. He was certainly a dairy farmer as well as a publican, as we find him named as such on the 1911 census, but either he was renting land from someone else, or it was a very small operation, as a Valuation Office Survey map produced in 1910 (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5) confirms the earlier newspaper account of 1897 that the 161 acres of land associated with the inn in 1840 had shrunk to only 13 acres, but also provides the additional information that the rest of the land had been subsumed into the new Black Horse Farm.

This new state of affairs is illustrated on the extract below from the 1910 map, with the Black Horse Inn and its land coloured green and numbered 56, while the Black Horse Farm is coloured yellow and numbered 17. Making matters worse for Philip, the Newport Pagnell line branch of the LNWR railway line (established 1865) bisects his land, effectively cutting it in two. What we do not know, is when the redistribution of land between inn and farm occurred; it might for instance have been prompted by the arrival of the railway, but for now the date proves illusive.

This new state of affairs is illustrated on the extract below from the 1910 map, with the Black Horse Inn and its land coloured green and numbered 56, while the Black Horse Farm is coloured yellow and numbered 17. Making matters worse for Philip, the Newport Pagnell line branch of the LNWR railway line (established 1865) bisects his land, effectively cutting it in two. What we do not know, is when the redistribution of land between inn and farm occurred; it might for instance have been prompted by the arrival of the railway, but for now the date proves illusive.

The 1910 Valuation Office Survey map also provides the additional detail that the Black Horse Inn also included some additional buildings and a workshop, in keeping with the previously recounted stories of it been used as a gym and a bicycle repair shop. We also learn that the inn and all its land and ancillary building are in the ownership of the Lord of the Manor, William Uthwatt. From the 1911 census, we learn that Philip's full name was Philip Lang Middleweek, and that living at the Black Horse Inn are his two elderly parents, Frank and Ann, as well as a sibling Francis. Philip was born in Ugborough in Devon on March 26th, 1878, and though all his siblings had been born in Devon, his father Frank was a native of Belfast in Ireland.

Philip married in 1915 to an Emma Jane Tillyard from Yardley Gobion, and in the same year he is listed as the publican of the Black Horse in the Kelly’s trade directory. They had two children together, Beryl in 1919 and Phillip in 1921, though both were born at Sherrington. Philip was still registered on the 1931 electoral roll for Great Linford as an owner of land at the Black Horse, but as a resident of Sherrington. However, Philip’s brother Edwin and wife Edith are shown at the inn on the 1921-1923 electoral rolls, though on the 1921 census Edwin is described as a cow keeper. Frustratingly there are no specific addresses provided on this document, but we do seem to have further evidence that some kind of limited farming activity was continuing at the inn.

Interestingly, present in the household on the 1921 census is a servant recorded as working at The Black Horse, and Edwin was undoubtedly still closely involved, as in October 1923, he is the plaintiff in a case involving the Black Horse. As reported in the Northampton Chronicle and Echo of October 23rd, Edwin had successfully sued a Fred Power, a “business transfer agent” from Shepherds Bush for £28, 19 shillings, the balance of purchase money on the transfer of the Black Horse Inn.

Most significantly, Edwin had told the court that he has put the Black Horse up for sale (so we can infer that the Uthwatts had sold the inn at some point after 1910), but had received only £641 from the defendant, not the £670 expected. The legal problems aside, it is interesting to note that until at least 1931 (according to the electoral rolls), Philip Middleweek (though residing at Sherrington), continued to exercise voting rights in Great Linford through land whose address is given as the Black Horse.

Philip married in 1915 to an Emma Jane Tillyard from Yardley Gobion, and in the same year he is listed as the publican of the Black Horse in the Kelly’s trade directory. They had two children together, Beryl in 1919 and Phillip in 1921, though both were born at Sherrington. Philip was still registered on the 1931 electoral roll for Great Linford as an owner of land at the Black Horse, but as a resident of Sherrington. However, Philip’s brother Edwin and wife Edith are shown at the inn on the 1921-1923 electoral rolls, though on the 1921 census Edwin is described as a cow keeper. Frustratingly there are no specific addresses provided on this document, but we do seem to have further evidence that some kind of limited farming activity was continuing at the inn.