Great Linford Manor Park

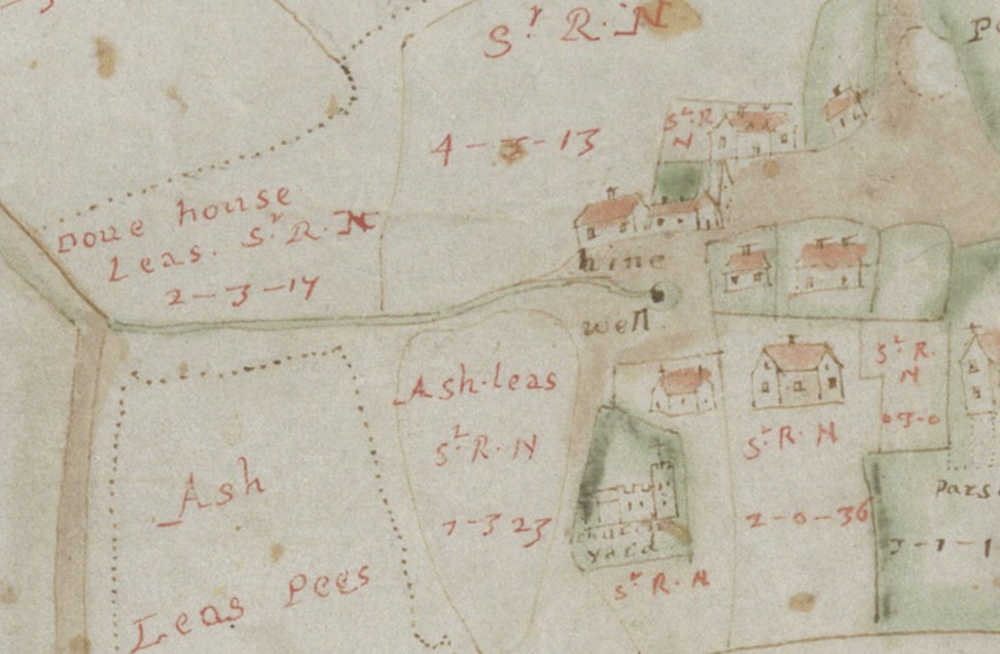

The extensive green spaces of Great Linford Manor Park are undoubtedly now much altered in appearance from the very first pleasure gardens commissioned by the lords of the manor. Prior to this, the vista presented to the observer would have been markedly less scenic. Referring back to estate maps drawn up in 1641 and 1678, it is evident that Great Linford High Street actually continued down into what is now the manor park grounds as far as the Hine Spring. This now serves as the water supply for the ornamental ponds, but was then a well. This provided water to the households who lived at this end of the street, and later to the residents of the Almshouses built circa 1700. Interestingly, Hine is an old English word for a peasant, servant or labourer, therefore we can think of it as the common person's spring.

The evolution of an English country pleasure garden

The history we have to hand does not tell us when the High Street dwellings were demolished and the first manor gardens were conceived and established, but perhaps the seed of change was planted with the purchase of the Great Linford Manor estate in 1678 by Sir William Prichard (also spelt Pritchard.) He began a considerable transformation of the land, by demolishing the old medieval mansion house and constructing in its stead the core of the building that now dominates the park.

As a rich London merchant looking to show off his newly acquired country seat, he would have most likely also wanted to compliment a prestigious manor house with an impressive garden. Equally however, he would not have wanted to look out his front windows at a street of common homes and hovels. It seems then that he would have been strongly motivated to remodel the estate grounds to suit the prevailing garden fashions of the time. Presumably his poor tenants were unceremoniously moved on.

Though we have no written evidence to prove that he commissioned any such work within what are now the public grounds before his death in 1704, to the rear of the manor house are the remnants of terraced garden. This is redolent of designs dated to the late 17th century. Prichard may very well then have commissioned a grand garden to go with his palatial country home. Though now largely lost to view, it is thought that the four terraces would have been fronted by retaining walls made of brick, with each section ascended by steps. Each terrace would have had distinct plantings and layouts to create a pleasant and impressive progression as guests promenaded through the grounds.

English gardens had been heavily influenced by the kind of formalised designs epitomised by Versailles in France, featuring impressive water features, statues and meticulously laid out geometric arrangements of flower beds and hedges. The principle aim was to astonish guests, with great houses vying enviously with one another to create the most impressive (and expensive) looking gardens.

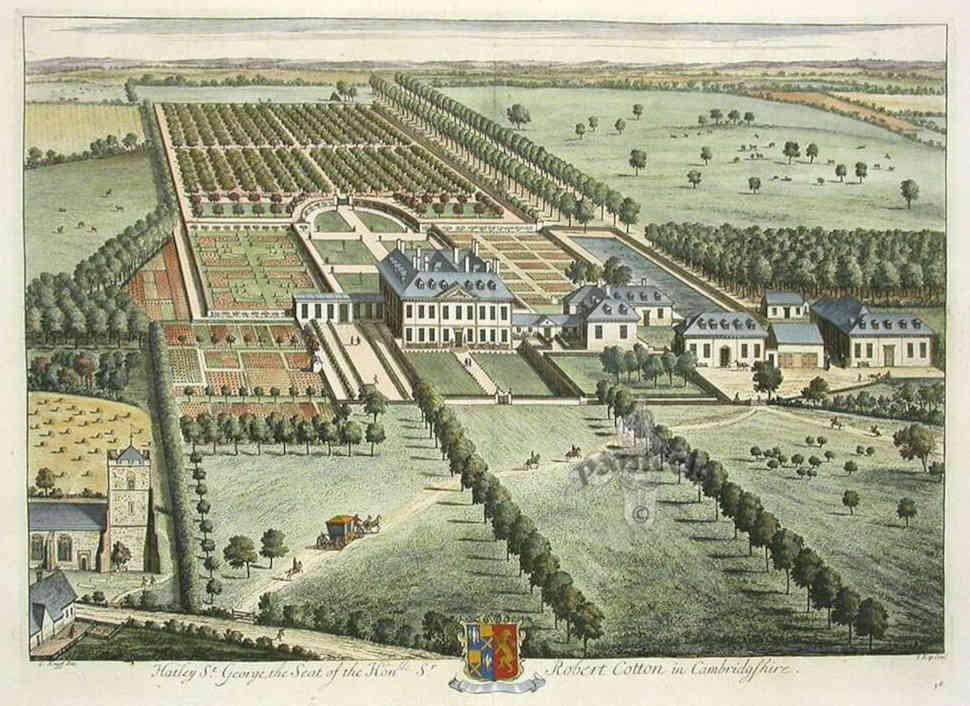

It has been suggested that the gardens of Hatley Park in Cambridgeshire would have had similar characteristics to those at Great Linford (see picture below.) However by the early 1700s the trend was moving toward a style that attempted to present an idealised view of the English countryside. Out went the precisely laid out gardens, in came pastoral landscapes of gently rolling lawns, dotted with trees, lakes and various architectural follies such as Greek style temples and gothic ruins. A particularly fine surviving example is Stowe Park in Buckinghamshire, whose head gardener was the famous designer Capability Brown.

As a rich London merchant looking to show off his newly acquired country seat, he would have most likely also wanted to compliment a prestigious manor house with an impressive garden. Equally however, he would not have wanted to look out his front windows at a street of common homes and hovels. It seems then that he would have been strongly motivated to remodel the estate grounds to suit the prevailing garden fashions of the time. Presumably his poor tenants were unceremoniously moved on.

Though we have no written evidence to prove that he commissioned any such work within what are now the public grounds before his death in 1704, to the rear of the manor house are the remnants of terraced garden. This is redolent of designs dated to the late 17th century. Prichard may very well then have commissioned a grand garden to go with his palatial country home. Though now largely lost to view, it is thought that the four terraces would have been fronted by retaining walls made of brick, with each section ascended by steps. Each terrace would have had distinct plantings and layouts to create a pleasant and impressive progression as guests promenaded through the grounds.

English gardens had been heavily influenced by the kind of formalised designs epitomised by Versailles in France, featuring impressive water features, statues and meticulously laid out geometric arrangements of flower beds and hedges. The principle aim was to astonish guests, with great houses vying enviously with one another to create the most impressive (and expensive) looking gardens.

It has been suggested that the gardens of Hatley Park in Cambridgeshire would have had similar characteristics to those at Great Linford (see picture below.) However by the early 1700s the trend was moving toward a style that attempted to present an idealised view of the English countryside. Out went the precisely laid out gardens, in came pastoral landscapes of gently rolling lawns, dotted with trees, lakes and various architectural follies such as Greek style temples and gothic ruins. A particularly fine surviving example is Stowe Park in Buckinghamshire, whose head gardener was the famous designer Capability Brown.

We do know that Henry Uthwatt (1728-1757) who inherited the Great Linford manor estate did business in the 1750s with a Brompton based garden nursery company owned by a Henry Hewitt. He paid just over £25 (about £3000 in today’s money) for his services. Henry Hewitt was a supplier of vegetable and flower seeds, bulbs bought from Holland, and seedlings of various ornamental trees, shrubs and fruit trees. This transaction would certainly seem to hint strongly that work was taking place to create or maintain a formal garden of some kind at Great Linford Manor at the time.

After Henry Uthwatt’s death at the untimely age of 29, the estate was occupied under the terms of his will by his widow Frances. Henry had appointed a gentleman named Sir Roger Newdigate as executor, so it was likely he who effectively held the purse strings to the family funds. Sir Roger owned the large Arbury estate in Nuneaton, Warwickshire and is credited with having overseen the transformation of the gardens there into the new informal landscape style. It is not unreasonable to suppose that he might have had a hand in works at Great Linford as well.

It is perhaps noteworthy that Frances Uthwatt had grown up at Chicheley Hall in Northamptonshire. These gardens just happened to have had some similar features to Great Linford’s manor gardens; a wilderness, a pavilion and a series of four descending rectangular ponds. Might Frances have wielded some influence over the design, perhaps to recreate some semblance of familiarity to her old home?

Garden designer Richard Woods

As no records exist, such as plans or payments made, the name of a garden designer at Great Linford can only be speculated upon, but a credible candidate would be Richard Woods (1715/16-1793). A contemporary of Capability Brown, Woods laid out plans for gardens at Little Linford in 1761. This had intriguing design similarities to Great Linford. Woods had a flair for getting the best out of small scale settings, combining gently undulating landscapes with so called Elysian walks. So while it is fair to say that the manor at Great Linford lacked space for a truly grand scale garden landscape, it does seem exactly the sort of commission that would suit his talents. Given that there was also a family connection between the manors of Great and Little Linford at the time, it seems entirely plausible to imagine that he worked at both properties.

Frances Uthwatt passed away in 1800 having survived her husband by 43 years. That there were gardens and ponds established at the time of her demise is certain. We know this because Henry Uthwatt Andrewes (1755-1812) who was next in line for the estate, became engaged in an ultimately fruitless battle to protect them from the ravages of the Grand Junction Canal company. They had obtained a compulsory land purchase order to drive their industrial waterway through the heart of the manor pleasure gardens. This prompted Henry to furiously remark, “Would any gentleman like to have such a nuisance near his garden or in view of it?”. For more on the story of the canal and its passage through the estate, visit the Grand Junction Canal page on this site.

Frances Uthwatt passed away in 1800 having survived her husband by 43 years. That there were gardens and ponds established at the time of her demise is certain. We know this because Henry Uthwatt Andrewes (1755-1812) who was next in line for the estate, became engaged in an ultimately fruitless battle to protect them from the ravages of the Grand Junction Canal company. They had obtained a compulsory land purchase order to drive their industrial waterway through the heart of the manor pleasure gardens. This prompted Henry to furiously remark, “Would any gentleman like to have such a nuisance near his garden or in view of it?”. For more on the story of the canal and its passage through the estate, visit the Grand Junction Canal page on this site.

The Hine Spring and cascading ponds

If it was Richard Woods who designed the gardens at Great Linford, he made good use of the available space, utilising the aforementioned Hine Spring to feed a series of cascading ponds in the manor grounds. The estate maps of the parish drawn up in 1641 and 1678 provide a rather conflicted view of the landscape as it then was, with the 1641 map showing the "Hine Well" as the source of a stream running down toward the Ouse valley, while the 1678 map shows a stream emanating from the grounds of the Parsonage, flowing into the Hine Spring and then onward toward the Ouse valley. While open to interpretation, both maps provide indications of a single pond in the vicinity of the Hine Spring. We do not know if this pond was natural or artificial, but if the latter, it may have been a so called stew pond, designed to hold a stock of fish for the table of the Lord of the Manor.

The first of the ponds we see today is perfectly round and clad in the local limestone. The next pond is more naturalist in style. It is speculated that a third pond was obliterated with the construction of the Grand Junction Canal, marooning a fourth still surviving pond below the far bank of the canal. Water would have originally cascaded from one to the other, doubtless creating a very pleasant effect for both eyes and ears.

The Wilderness

A garden feature once much desired by the discerning landowner was a Wilderness, though the name is somewhat misleading. It was not intended as might be imagined as a wild unkempt area. It was instead a carefully planned, planted and clearly marked out area of a wider garden landscape. The agricultural and religious essayist Timothy Nourse (c 1636-1699) described a Wilderness as follows. “Natural-Artificial; that is, let all things be dispos’d with that cunning, as to deceive us into a belief of a real Wilderness or Thicket, and yet to be furnished with all the Varieties of Nature.” The nature of a Wilderness has changed much over time, with the earliest designs emphasising blocks of vegetation with straight walks between them, but as time went on these walks were sometimes laid out in a more serpentine style.

Writing in his influential 1734 book The Gardner’s and Florist’s Dictionary, Philip Miller noted that Wildernesses, “if rightly situated, artfully contrived, and judiciously planted are the greatest ornaments to a fine garden.” However he was also rather scathing of the state of Wilderness design, adding the following caveat. “But it is rare to see these so well executed in Gardens, as to afford the Owner due Pleasure (especially if he is a Person of elegant Taste); for either they are so situated as to hinder a distant Prospect, or else are not judiciously planted.”

The roots of the Wilderness garden have been traced to Italian renaissance Bosco gardens of the late 15th century. In essence the word meant a natural grove or group of trees, though the origin of the word Wilderness in the context of a garden remains somewhat uncertain. It has been suggested that the name had a Biblical origin. Certainly words translated as “wilderness” are repeated in various contexts some 300 times in the Bible. Notably these are stories that deal with searching for truth and meaning in isolated spaces. Perhaps then the winding paths to be travelled and discoveries to be made in a garden Wilderness have an allegorical connection to the Bible. It has also been suggested that a Wilderness served as a statement of man’s control over nature.

Wildernesses were at the height of their popularity between 1690-1750, with a peak probably coming between 1735-40. If Richard Woods designed the gardens circa 1761 and the Wilderness formed part of that design, then you might reasonably argue that his approach was for the time rather old fashioned. Of course the revolution in garden design championed by the likes of Capability Brown that erased many Wildernesses from grand English gardens did not sweep the country overnight, so perhaps in Buckinghamshire at the time a Wilderness was still considered fashionable.

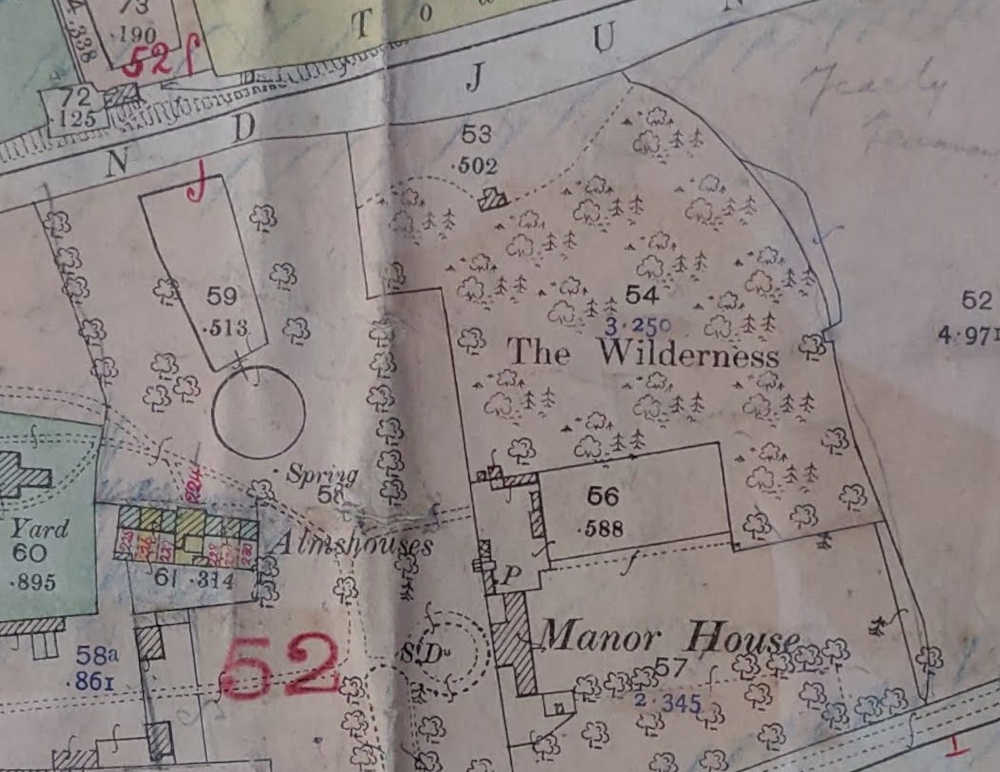

Specific mentions of the Wilderness at Great Linford seem to be few and far between. The 1840 tithe map for the village (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) is quite light on detail and does not specifically label the wilderness, though later maps do. Notably, Ordnance Survey maps provide that the Wilderness once extended as far as the manor house wall, so much larger than the small rump that now remains. Click here to view the 1881 O.S map. The 1910 Valuation Office Survey map (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5), itself based on an O.S map, also clearly shows the larger extent of the Wilderness.

Writing in his influential 1734 book The Gardner’s and Florist’s Dictionary, Philip Miller noted that Wildernesses, “if rightly situated, artfully contrived, and judiciously planted are the greatest ornaments to a fine garden.” However he was also rather scathing of the state of Wilderness design, adding the following caveat. “But it is rare to see these so well executed in Gardens, as to afford the Owner due Pleasure (especially if he is a Person of elegant Taste); for either they are so situated as to hinder a distant Prospect, or else are not judiciously planted.”

The roots of the Wilderness garden have been traced to Italian renaissance Bosco gardens of the late 15th century. In essence the word meant a natural grove or group of trees, though the origin of the word Wilderness in the context of a garden remains somewhat uncertain. It has been suggested that the name had a Biblical origin. Certainly words translated as “wilderness” are repeated in various contexts some 300 times in the Bible. Notably these are stories that deal with searching for truth and meaning in isolated spaces. Perhaps then the winding paths to be travelled and discoveries to be made in a garden Wilderness have an allegorical connection to the Bible. It has also been suggested that a Wilderness served as a statement of man’s control over nature.

Wildernesses were at the height of their popularity between 1690-1750, with a peak probably coming between 1735-40. If Richard Woods designed the gardens circa 1761 and the Wilderness formed part of that design, then you might reasonably argue that his approach was for the time rather old fashioned. Of course the revolution in garden design championed by the likes of Capability Brown that erased many Wildernesses from grand English gardens did not sweep the country overnight, so perhaps in Buckinghamshire at the time a Wilderness was still considered fashionable.

Specific mentions of the Wilderness at Great Linford seem to be few and far between. The 1840 tithe map for the village (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) is quite light on detail and does not specifically label the wilderness, though later maps do. Notably, Ordnance Survey maps provide that the Wilderness once extended as far as the manor house wall, so much larger than the small rump that now remains. Click here to view the 1881 O.S map. The 1910 Valuation Office Survey map (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5), itself based on an O.S map, also clearly shows the larger extent of the Wilderness.

The 1925 O.S map again shows the Wilderness extending to the manor walls, but with the addition of the access road to the side of the manor house. Click here to view the 1925 O.S map. Exactly when the Wilderness was pared back so brutally is uncertain, but the arrival in 1956 of the Chilstone garden ornament company in 1956 as the new tenants of the manor house may be significant, as subsequently a large area to the side of the manor was given over to a carpark for customers.

An interesting reference is made to the Wilderness in a criminal case of 1893, reported in Croydon's Weekly Standard newspaper of Saturday July 1st, 1893. Appearing before the Newport Pagnell Petty Sessions, Gerard Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt testified that he had apprehended a man for shooting a duck at about 4pm on the afternoon of June 18th. Uthwatt had been in his manor garden when he heard a gunshot, and hastening in the direction of the shot observed, “the defendant jump off a boat on the canal, and go into the wilderness which adjoins the canal.”

Making his presence known, Uthwatt recovered a mortally wounded Duck and apprehended the boatman. So from this account we can see that the Wilderness was still very much a recognised part of the manor gardens at this time. Turning to the later 1911 tax map, we find it very clearly depicted and unambiguously named as such. While the map is not sufficiently detailed to show any paths extant at the time, the aforementioned Doric Seat is plainly visible. Notably the Wilderness is much larger in extent than the part that remains today, extending as far as the walled manor garden, and with its eastern extent clearly marked out by the line of what must have been the Ha Ha.

A wilderness is mentioned In Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. Lady Catherine de Bourgh suggests to Elizabeth Bennet that, "there seemed to be a prettyish kind of a little wilderness at the side of your lawn. I should be glad to take a turn in it, if you will favour me with your company."

An interesting reference is made to the Wilderness in a criminal case of 1893, reported in Croydon's Weekly Standard newspaper of Saturday July 1st, 1893. Appearing before the Newport Pagnell Petty Sessions, Gerard Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt testified that he had apprehended a man for shooting a duck at about 4pm on the afternoon of June 18th. Uthwatt had been in his manor garden when he heard a gunshot, and hastening in the direction of the shot observed, “the defendant jump off a boat on the canal, and go into the wilderness which adjoins the canal.”

Making his presence known, Uthwatt recovered a mortally wounded Duck and apprehended the boatman. So from this account we can see that the Wilderness was still very much a recognised part of the manor gardens at this time. Turning to the later 1911 tax map, we find it very clearly depicted and unambiguously named as such. While the map is not sufficiently detailed to show any paths extant at the time, the aforementioned Doric Seat is plainly visible. Notably the Wilderness is much larger in extent than the part that remains today, extending as far as the walled manor garden, and with its eastern extent clearly marked out by the line of what must have been the Ha Ha.

A wilderness is mentioned In Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice. Lady Catherine de Bourgh suggests to Elizabeth Bennet that, "there seemed to be a prettyish kind of a little wilderness at the side of your lawn. I should be glad to take a turn in it, if you will favour me with your company."

The Doric Seat

The remains of Great Linford manor’s Doric Seat are to be found close by the canal bank and hidden away in the Wilderness. It would have once boasted an unhindered view over the Ouse valley, the obscuring tree line that now exists having grown up along the canal and railway lines that bisected the estate. Unfortunately the Doric Seat is now reduced to a shadow of its former self, having suffered a rather ignoble end as a cow shed (the concrete additions of feed troughs can still be seen.) It finally succumbed to vandalism and a fire in the 1980s. In its heyday it boasted ornate Greek style Doric columns and would have been a tranquil spot to escape the formalities of manor house life. One can imagine the lady of the manor and her guests strolling to the seat on a sunny afternoon, perhaps with cooling drinks and a picnic-spread carried by servants.

In another nod to the idea that Richard Woods had a hand in creating the gardens at Great Linford, his plans for Little Linford included a “light Doric." To this has become attached a lovely, but perhaps unlikely tale. As mentioned previously, there was once a family connection with the estates of Great and Little Linford. Catherine Uthwatt (1724-1794) of Great Linford was the daughter of Thomas and Catherine Uthwatt, nee Dalton. She married Matthew Knapp on June 19th, 1750 and departed to live with her new husband at his estate in Little Linford, apparently leaving her mother much bereft at the loss. The story goes that she would sit in the Doric Seat, gazing across the Ouse valley toward Little Linford, imagining that her daughter was sat on her twin Doric Seat. Thus they would silently and sadly commune across the space that separated them.

It is a charming story, but the chronology is troublesome. To begin with, we know Richard Woods laid out his plans for Little Linford in 1761, hence well after the marriage of Catherine Uthwatt and Matthew Knapp in 1750. So for the first decade of the separation of mother and daughter, there was no Doric Seat at Little Linford. But there is more to cast doubt on the tale. Thomas Uthwatt died in 1754, and if we accept that Woods was the designer of Great Linford’s gardens and hence the Doric Seat in which the anguished mother sat, it seems likely that the commission was made during Thomas’s lifetime. This would make it the earliest known work by Woods, which also seems unlikely. We also know that after Thomas died, his widow moved away, when it is not clear, but she passed away at her residence at Great George Street in London in 1769. All added up, the story seems then problematic, but there might easily be a grain of truth in the tale. Doric Seat or not, there is every possibility that a disconsolate mother may indeed have found a lonely vantage point in the manor grounds, there to seek some solace by looking toward her daughter’s home at Little Linford.

In another nod to the idea that Richard Woods had a hand in creating the gardens at Great Linford, his plans for Little Linford included a “light Doric." To this has become attached a lovely, but perhaps unlikely tale. As mentioned previously, there was once a family connection with the estates of Great and Little Linford. Catherine Uthwatt (1724-1794) of Great Linford was the daughter of Thomas and Catherine Uthwatt, nee Dalton. She married Matthew Knapp on June 19th, 1750 and departed to live with her new husband at his estate in Little Linford, apparently leaving her mother much bereft at the loss. The story goes that she would sit in the Doric Seat, gazing across the Ouse valley toward Little Linford, imagining that her daughter was sat on her twin Doric Seat. Thus they would silently and sadly commune across the space that separated them.

It is a charming story, but the chronology is troublesome. To begin with, we know Richard Woods laid out his plans for Little Linford in 1761, hence well after the marriage of Catherine Uthwatt and Matthew Knapp in 1750. So for the first decade of the separation of mother and daughter, there was no Doric Seat at Little Linford. But there is more to cast doubt on the tale. Thomas Uthwatt died in 1754, and if we accept that Woods was the designer of Great Linford’s gardens and hence the Doric Seat in which the anguished mother sat, it seems likely that the commission was made during Thomas’s lifetime. This would make it the earliest known work by Woods, which also seems unlikely. We also know that after Thomas died, his widow moved away, when it is not clear, but she passed away at her residence at Great George Street in London in 1769. All added up, the story seems then problematic, but there might easily be a grain of truth in the tale. Doric Seat or not, there is every possibility that a disconsolate mother may indeed have found a lonely vantage point in the manor grounds, there to seek some solace by looking toward her daughter’s home at Little Linford.

Excavations in 2019

Excavations were conducted in 2019 revealing several stone walls that pass beneath the remains of the Doric Seat, indicating that these are older. It seems likely that these walls were robbed out and the stone used as a rubble foundation layer for the Doric Seat. The 1911 tax map gives an outline for the Doric Seat, indicating it may have been a squat T shape rather than the oblong base that now remains. The map is very precise in terms of the outlines of buildings, so we can be confident this represents a truthful reflection of the original shape.

The Ha Ha

In order the preserve the illusion of a country garden unmarred by unsightly fencing or walls, it was common for garden designers to incorporate a Ha Ha into their landscapes. A Ha Ha was in essence a sunken wall, so to the observer there would appear to be an uninterrupted view of the countryside. This created the illusion of a much larger garden. From a practical standpoint, livestock could be grazed close to the gardens, but would be prevented from straying within.

The origin of the name Ha Ha is not entirely certain, but one theory suggests it was so named after the exclamation of surprise a visitor would make upon stumbling across the unexpected barrier. Another rather drier explanation had it that the name is derived from an abbreviation of half wall, half ditch.

The Ha Ha at Great Linford had until very recently practically vanished from living memory and view, with only portions of the filled in ditch evident. Thanks to the excavations carried out in 2019 by Cotswold Archaeology, a section was exposed and found to be in surprisingly good condition. In late 2020, further archaeological investigations were begun to trace the line of the Ha Ha, with the possibility of exposing and restoring even more of it to view.

The origin of the name Ha Ha is not entirely certain, but one theory suggests it was so named after the exclamation of surprise a visitor would make upon stumbling across the unexpected barrier. Another rather drier explanation had it that the name is derived from an abbreviation of half wall, half ditch.

The Ha Ha at Great Linford had until very recently practically vanished from living memory and view, with only portions of the filled in ditch evident. Thanks to the excavations carried out in 2019 by Cotswold Archaeology, a section was exposed and found to be in surprisingly good condition. In late 2020, further archaeological investigations were begun to trace the line of the Ha Ha, with the possibility of exposing and restoring even more of it to view.

The Lime Tree

Within the Wilderness you will find Great Linford’s ancient Lime tree, not it should be noted a tree that produces Lime fruit. This venerable old tree is thought to be between 300-500 years old, and probably one of the oldest trees in Milton Keynes. The somewhat odd shape is attributed to it having been pollarded, which is a method of pruning that removes the upper branches of a tree on a regular cycle, typically every eight to fifteen years. It has been estimated that this took place about 150 years ago. Pollarding was often done for the purpose of producing wood growth for construction such as long straight fence posts. Lime tree wood is typically used for wood turning, carving and furniture making, so perhaps a local artisan had marked the Lime tree down as a valuable source of materials. Another possibility is that damage occurred during the construction of the Grand Junction Canal, which necessitated Pollarding. The process is also said to extend the lifetime of a tree, so given that a Lime tree is typically thought to live about 200 years, this might well explain the longevity of this particular example.

Lime trees are also known as Linden trees, which has led to speculation that the name Great Linford is derived from a ford over a river (the Ouse?) near a Linden tree. However, there are some alternative theories. The old English word for a Maple tree is hlin or hyln, so this too may point to an origin for the name Linford. Equally, suggestions have been made that it may be derived from another old English word, lin, for flax, linen or cloth. Given that the manufacture of linen cloth requires a good supply of water, and we know Great Linford was well served by springs and a stream in the manor grounds, this theory may also be worth considering.

Lime trees are also known as Linden trees, which has led to speculation that the name Great Linford is derived from a ford over a river (the Ouse?) near a Linden tree. However, there are some alternative theories. The old English word for a Maple tree is hlin or hyln, so this too may point to an origin for the name Linford. Equally, suggestions have been made that it may be derived from another old English word, lin, for flax, linen or cloth. Given that the manufacture of linen cloth requires a good supply of water, and we know Great Linford was well served by springs and a stream in the manor grounds, this theory may also be worth considering.

Lost features

Though the Uthwatt’s fought tooth and nail to preserve their pleasure gardens from the encroachment of the Grand Junction Canal, it seems that in later years they made peace with the reality of the situation. Referring to the Ordnance Survey map of 1881 a notation is included for a boat house located just on the edge of The Wilderness. This would seem to indicate that the Uthwatts had taken up pleasure boating on the canal. No sign of this structure remains today.

In 1864, the Reverend William Andrewes Uthwatt became embroiled in a bitter argument with the Newport Pagnell Railway Company regarding a suitable level of compensation for land it had taken by compulsory purchase for their route. In the course of testimony at a court case brought by the Reverend Uthwatt, passing mention was made of a summer house in the manor grounds. Was this the Doric Seat by another name, or was there an additional structure in the grounds that has since vanished from view? For more on this court case and its impact on the gardens, see the page on this site about the Newport Pagnell Railway.

In 1864, the Reverend William Andrewes Uthwatt became embroiled in a bitter argument with the Newport Pagnell Railway Company regarding a suitable level of compensation for land it had taken by compulsory purchase for their route. In the course of testimony at a court case brought by the Reverend Uthwatt, passing mention was made of a summer house in the manor grounds. Was this the Doric Seat by another name, or was there an additional structure in the grounds that has since vanished from view? For more on this court case and its impact on the gardens, see the page on this site about the Newport Pagnell Railway.