Grange Farm (formally Green Farm) Great Linford

Grange Farm is located on Harper’s Lane, (previously known as Willen Lane) and like all the surviving farm buildings in the parish is now a private home, with its acres of former farmland subsumed beneath modern development and housing. However, it was not always known as Grange Farm, having previously operated as Green Farm. We know this as it is clearly labelled as such on a number of maps, such as the 1881 Ordnance Survey map. The book A Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes (1986, Paul Woodfield, Milton Keynes Development Corporation) provides the following description of the farm.

An extensive building along the south side of the road, of the 18th century and with a central wing to the south, probably 17th century. Colourwashed with a slate roof over older roof structure. The upper floor of the roadside wing is claimed to have been a wool store. Internally there is an inglenook fireplace with an oven projecting on the south side. The farm buildings stood a short way to the south and were demolished in 1976..

The Mead

Running throughout the history of the Grange Farm is the question, what part does the nearby house known as The Mead play in the story? The Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes describes The Mead as a farmhouse, but a close examination of available records finds no reference to a farm or dwelling of this name, though it may be a recent appellation. Complicating matters, there is every indication that The Mead and The Grange Farm were once part of a large, combined farming enterprise with a single occupier. The full description offered in The Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes is as follows.

Farmhouse, Circa 17th century. A substantial stone building of two storeys, three bays with a lobby plan. The windows have timber lintels. Two gable stacks, one having been added at a later date.

Two generation of Rawlins

We can speculate that the farm (rather unimaginatively) was named Green Farm simply due to its proximity to the village green. As to the farm's tenants, we can plausibly place several generations of the Rawlins family at the farm from as early as 1757 thanks to a Mortgage by Release (D-BAS/41/178) between Henry Uthwatt esquire of Great Linford Manor and his wife Frances, plus a John Maire esquire of Grey's Inn in Middlesex and a James Buchanan of Mark Lane, London, a merchant.

This document describes an unnamed messuage (an old term for house) in the occupation of a George Rawlins for a rent of £110. Crucially, the document also makes reference to five fields in his occupation: Herns House Close, First Long Ground, Second Long Ground, Third Long Ground and Nicholas Mead, measuring all together 134 acres, two roods and 34 perches, the latter two figures being old terms of measurement. Two of these fields, Herns House Close and Nicholas Mead, can be identified on an estate map drawn up in 1641, and significantly both fields are to be found in close proximity to the modern-day location of Grange Farm and The Mead.

George Rawlins was born at Great Linford in 1735, the son of John Rawlins and Jane Clerk; they had been married at St. Andrew’s church on January 7th, 1730, and the couple had at least six children, George amongst them. George passed away in 1784 at the age of 49, leaving a widow named Lydia. A person we can presume to be their eldest son John (born 1760) is named as a farmer of 199 acres on an indenture drawn up in 1808 by the Uthwatts of Great Linford Manor (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X_2228.) Again, we can draw some pertinent conclusions from field names, as a comparison between the indenture of 1808 and a tithe map of the area drawn up in 1840 (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255), gives us two matching fields, Tongwell Meadow and East Rushby Grounds.

As the tithe map clearly pinpoints the farmstead of Grange Farm in the landscape we can be reasonably confident in connecting the fields and perhaps the tenancy of Grange Farm to John Rawlins, arguably making him the second generation of the family to occupy the farm. John passed away on April 1st, 1817. aged 57 and was buried in St. Andrew’s churchyard. A collection of Rawlins gravestones can still be seen in the churchyard. In his will (proved on November 21st, 1821) John describes himself as a “farmer and dairyman."

As a matter of pure conjecture, the field name “Herns House Close” does offer the intriguing possibility that a person named Hern was previously associated with the property, and indeed there is a Hearne family sporadically recorded in the parish records during the late 1600s, so perhaps the Herns were the first occupants of the farmhouse.

This document describes an unnamed messuage (an old term for house) in the occupation of a George Rawlins for a rent of £110. Crucially, the document also makes reference to five fields in his occupation: Herns House Close, First Long Ground, Second Long Ground, Third Long Ground and Nicholas Mead, measuring all together 134 acres, two roods and 34 perches, the latter two figures being old terms of measurement. Two of these fields, Herns House Close and Nicholas Mead, can be identified on an estate map drawn up in 1641, and significantly both fields are to be found in close proximity to the modern-day location of Grange Farm and The Mead.

George Rawlins was born at Great Linford in 1735, the son of John Rawlins and Jane Clerk; they had been married at St. Andrew’s church on January 7th, 1730, and the couple had at least six children, George amongst them. George passed away in 1784 at the age of 49, leaving a widow named Lydia. A person we can presume to be their eldest son John (born 1760) is named as a farmer of 199 acres on an indenture drawn up in 1808 by the Uthwatts of Great Linford Manor (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X_2228.) Again, we can draw some pertinent conclusions from field names, as a comparison between the indenture of 1808 and a tithe map of the area drawn up in 1840 (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255), gives us two matching fields, Tongwell Meadow and East Rushby Grounds.

As the tithe map clearly pinpoints the farmstead of Grange Farm in the landscape we can be reasonably confident in connecting the fields and perhaps the tenancy of Grange Farm to John Rawlins, arguably making him the second generation of the family to occupy the farm. John passed away on April 1st, 1817. aged 57 and was buried in St. Andrew’s churchyard. A collection of Rawlins gravestones can still be seen in the churchyard. In his will (proved on November 21st, 1821) John describes himself as a “farmer and dairyman."

As a matter of pure conjecture, the field name “Herns House Close” does offer the intriguing possibility that a person named Hern was previously associated with the property, and indeed there is a Hearne family sporadically recorded in the parish records during the late 1600s, so perhaps the Herns were the first occupants of the farmhouse.

The Elkins; another family affair

Though we are hampered with a short gap in the records, we can next place two generations of the Elkins family at the farm, the first of whom was Joseph Elkins, born circa 1765. We do not know where Joseph was born, but he was married in Gayhurst, Buckinghamshire to a Mary Kilpin on December 1st, 1791. The couple raised a family there, numbering at least nine, and as evidenced by their children’s baptisms, the Elkins were non-conformists.

We have several sources that serve to pinpoint the family’s arrival in Great Linford between late 1824 and 1825. In 1822, the Northampton Mercury of February 16th, reported that Joseph Elkins was to leave his farm at Gayhurst, then on November 27th, 1824, the same newspaper reports that a Joseph Elkins was to leave the Potterspury Lodge Farm in Northamptonshire. Whilst we have no evidence to prove that this is the same person, the name Joseph Elkins is sufficiently rare that we might reasonably join the dots. Of more compelling evidential value, on December 28th, 1825, Joseph’s daughter Leah was married at Great Linford to a William Bailey Pratt, a draper of Newport Pagnell. This certainly seems to suggest a narrow one-year window for the arrival of the Elkins at Great Linford.

Joseph died on January 18th, 1830, at the age of 65. A brief announcement of his death in the Bucks Gazette of January 30th places him at Great Linford, though he was actually buried at Gayhurst. On the death of Joseph, the tenancy of Green Farm then passed to his eldest son Eli. Thanks to the non-conformist baptism records (that are generally more detailed than the Church of England records) we have Eli’s date of birth, July 27th, 1801.

Eli is mentioned in the Bucks Gazette of April 13th, 1833, in connection to a theft that took place at Great Linford. Eli was the victim, having had eight ox chains purloined by a man in his service called Thomas Mott. It seems it was a cast iron case, as the chains were discovered in the bedroom of the accused. Mott had previous form, having been convicted of damaging a wall in 1827, and in 1829 of stealing lead. A juror who knew the defendant attested that he had known him for some 20 years and had occasionally employed him. He had worked fairly, but “suffered much from want of employment.”

As a farmer, Eli would have been considered a man of good character, and as such we find him elected as a guardian for Great Linford in October 1835 and frequently again in the years following, with the last such appointment occurring in 1871. As a guardian, he would have had responsibility for ascertaining the needs of the poor and distributing funds and support for those judged wanting. Though we cannot attest to the fact of his election every intervening year, it none-the-less represents an extraordinarily long record of service.

Being a local official was not without its difficulties, as is illustrated by an account of a court case entitled “Uthwatt vs Elkins and 4 others”, that was carried in the Northampton Mercury of July 20th, 1844. The case hinged on an agreement that the Lord of the Manor, Henry Andrewes Uthwatt had made with Eli and four other unnamed men in 1833, all of them at the time serving variously as overseers, church wardens and surveyors for the parish. We do not know in which role Eli was then serving in connection to this case, nor the names of his fellow defendants, but the agreement was to lease from Henry Uthwatt a plot of garden land that could be parcelled up and sublet to the poor of the parish.

Eli and his compatriots in this worthy endeavour made the first payment, but thereafter the bill was presented to, and paid by, those men who year after year succeeded them in office. This arrangement endured without incident, until in 1842 the bill went unpaid, and Henry sought restitution from the original signatories to the agreement. This Eli and his co-defendants argued was patently unfair, as they had signed the agreement not as private individuals, but as officials, and therefore it was the parish that was liable for the ongoing servicing of the debt. The case ended inconclusively, and the final settlement of the matter has not yet come to light.

Another indication of Eli’s status is his appearance in the 1837 and 1828 poll book entries for the parish. Only a small fraction of the men in the parish qualified under the rules of the time to vote in elections, the criteria being based on their income, which had to be £10 or more annually. It is hardly surprising that Eli had qualified to vote, as in addition to the 221 acres ascribed to Grange Farm, the tithe map drawn up for the parish in 1840 (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) shows that he also occupied the adjacent farmhouse now known as The Mead, plus Wood End Farm, the farmstead of which was located at the north end of Linford Wood. This added another 136 acres to the tally, a grand total of 357 acres with a combined rateable value of £78 and 15 shillings. Yet, despite all his success as a farmer, it is important to note that Eli was still only a tenant. The landowner of all three farms is listed on the tithe map as Henry Andrewes Uthwatt.

On the extract from the 1840 tithe map reproduced below, we can see Grange Farm and The Mead on opposite sides of the Willen Lane (the roadway marked in yellow), however, the accompanying indexes to the map make no distinction between the two farms, and indeed no farms are explicitly named. Grange Farm, numbered as 51, is described in the map's documentation as a "house and homestead", while The Mead numbered as 77, is described as a "homestead and Rik Hades", the latter being the name of the field that partially surrounds the house. The other fields and assets ascribed to the occupation of Eli Elkins are numbered #50a (Home Close), #52 (Fulwell Ground), #53 (Wetherheads and Duckheads), #54 (West Square Ground), #55 (Lane), #56 (East Square Ground), #57 (West Culvert Glade), #68 (Dry Sides), #69 (Lane), #70 (East Culvert Glade), #71 (East Fullwell), #72 (Caldecot Meadow), #73 (Tongwell Meadow), #74 (East Rushby Grounds), #75 (Middle Rushby Ground) and #82 (Town Green.)

We have several sources that serve to pinpoint the family’s arrival in Great Linford between late 1824 and 1825. In 1822, the Northampton Mercury of February 16th, reported that Joseph Elkins was to leave his farm at Gayhurst, then on November 27th, 1824, the same newspaper reports that a Joseph Elkins was to leave the Potterspury Lodge Farm in Northamptonshire. Whilst we have no evidence to prove that this is the same person, the name Joseph Elkins is sufficiently rare that we might reasonably join the dots. Of more compelling evidential value, on December 28th, 1825, Joseph’s daughter Leah was married at Great Linford to a William Bailey Pratt, a draper of Newport Pagnell. This certainly seems to suggest a narrow one-year window for the arrival of the Elkins at Great Linford.

Joseph died on January 18th, 1830, at the age of 65. A brief announcement of his death in the Bucks Gazette of January 30th places him at Great Linford, though he was actually buried at Gayhurst. On the death of Joseph, the tenancy of Green Farm then passed to his eldest son Eli. Thanks to the non-conformist baptism records (that are generally more detailed than the Church of England records) we have Eli’s date of birth, July 27th, 1801.

Eli is mentioned in the Bucks Gazette of April 13th, 1833, in connection to a theft that took place at Great Linford. Eli was the victim, having had eight ox chains purloined by a man in his service called Thomas Mott. It seems it was a cast iron case, as the chains were discovered in the bedroom of the accused. Mott had previous form, having been convicted of damaging a wall in 1827, and in 1829 of stealing lead. A juror who knew the defendant attested that he had known him for some 20 years and had occasionally employed him. He had worked fairly, but “suffered much from want of employment.”

As a farmer, Eli would have been considered a man of good character, and as such we find him elected as a guardian for Great Linford in October 1835 and frequently again in the years following, with the last such appointment occurring in 1871. As a guardian, he would have had responsibility for ascertaining the needs of the poor and distributing funds and support for those judged wanting. Though we cannot attest to the fact of his election every intervening year, it none-the-less represents an extraordinarily long record of service.

Being a local official was not without its difficulties, as is illustrated by an account of a court case entitled “Uthwatt vs Elkins and 4 others”, that was carried in the Northampton Mercury of July 20th, 1844. The case hinged on an agreement that the Lord of the Manor, Henry Andrewes Uthwatt had made with Eli and four other unnamed men in 1833, all of them at the time serving variously as overseers, church wardens and surveyors for the parish. We do not know in which role Eli was then serving in connection to this case, nor the names of his fellow defendants, but the agreement was to lease from Henry Uthwatt a plot of garden land that could be parcelled up and sublet to the poor of the parish.

Eli and his compatriots in this worthy endeavour made the first payment, but thereafter the bill was presented to, and paid by, those men who year after year succeeded them in office. This arrangement endured without incident, until in 1842 the bill went unpaid, and Henry sought restitution from the original signatories to the agreement. This Eli and his co-defendants argued was patently unfair, as they had signed the agreement not as private individuals, but as officials, and therefore it was the parish that was liable for the ongoing servicing of the debt. The case ended inconclusively, and the final settlement of the matter has not yet come to light.

Another indication of Eli’s status is his appearance in the 1837 and 1828 poll book entries for the parish. Only a small fraction of the men in the parish qualified under the rules of the time to vote in elections, the criteria being based on their income, which had to be £10 or more annually. It is hardly surprising that Eli had qualified to vote, as in addition to the 221 acres ascribed to Grange Farm, the tithe map drawn up for the parish in 1840 (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) shows that he also occupied the adjacent farmhouse now known as The Mead, plus Wood End Farm, the farmstead of which was located at the north end of Linford Wood. This added another 136 acres to the tally, a grand total of 357 acres with a combined rateable value of £78 and 15 shillings. Yet, despite all his success as a farmer, it is important to note that Eli was still only a tenant. The landowner of all three farms is listed on the tithe map as Henry Andrewes Uthwatt.

On the extract from the 1840 tithe map reproduced below, we can see Grange Farm and The Mead on opposite sides of the Willen Lane (the roadway marked in yellow), however, the accompanying indexes to the map make no distinction between the two farms, and indeed no farms are explicitly named. Grange Farm, numbered as 51, is described in the map's documentation as a "house and homestead", while The Mead numbered as 77, is described as a "homestead and Rik Hades", the latter being the name of the field that partially surrounds the house. The other fields and assets ascribed to the occupation of Eli Elkins are numbered #50a (Home Close), #52 (Fulwell Ground), #53 (Wetherheads and Duckheads), #54 (West Square Ground), #55 (Lane), #56 (East Square Ground), #57 (West Culvert Glade), #68 (Dry Sides), #69 (Lane), #70 (East Culvert Glade), #71 (East Fullwell), #72 (Caldecot Meadow), #73 (Tongwell Meadow), #74 (East Rushby Grounds), #75 (Middle Rushby Ground) and #82 (Town Green.)

In addition to Eli’s impressive activities in Great Linford, a notice in the Bucks Herald of May 8th, 1841, informs us that a farm of 101 acres at Caldecotte was for sale, and leased to Eli Elkins until Lady Day, which would have fallen on March 25th, 1842. Eli was however resident at Great Linford at the time of the 1841 census, which was held on the evening of June 6th. Unhelpfully, this census provides no clear information on where a person was living other than in the parish, so exactly where Eli was found by the enumerator on the night of the census remains uncertain. Indeed, exactly which house he called his primary residence must for now remain in doubt.

The census does however provide some useful information. In the same household at Great Linford in 1841 is Eli’s younger brother Thomas, both siblings described as farmers. Also present is 33-year-old Martha Thorpe, born 1808 at Preston Bissett, and whom we find mentioned in connection to an award made in 1842 by the Newport Pagnell Agricultural Association. The Northampton Mercury of October 1st reports that she received 30 shillings in recognition that she had been in Eli’s employ for seven years. Eli never married, but Martha was a constant in his life, and we can perhaps infer a close connection between the two, as she remained his housekeeper until his death. She herself never married, and her gravestone in St. Andrew’s churchyard states she, “was for above forty years the valued and respected housekeeper of Mr Elkins.”

Several other members of the extended Elkins family are present on the 1841 census, including William Pratt, who had married Leah Elkins in 1825, though the marriage was to prove tragically short lived, Leah having passed away shortly afterward. But William must have had an eye for the Elkins girls, as he wasted no time in wooing Leah’s 18-year-old younger sister Eliza, the pair marrying at St. Andrew Holborn in London on December 28th, 1826. The venue seems odd; perhaps there were some local quibbles with the propriety of the marriage, though the record states that the union had the consent of Joseph Elkins. By the time of the 1841 census, the couple had at least one child, Catherine, with mother and daughter both at the Great Linford farmstead.

Another of Joseph’s married daughters, 28-year-old Amelia is also present. She had married John Heygate on May 7th, 1839, at St. Andrews, Great Linford, though the couple made their home in Elkington, Northamptonshire, where they raised a family; indeed, on the night of the 1841 census, John was at Elkington with their baby daughter Mary.

Alongside his duties as a guardian, and as someone with sufficient income to qualify, Eli could also expect to be called upon to serve as a juror, and this was the case regarding one particularly important coroner’s inquest held in June 1847. On the night of Saturday June 5th, at approximately 10.45pm, the regularly scheduled train from Euston Square to Liverpool was approaching Wolverton, but due to human error, rather than make its appointed stop at the station, the train was redirected by the pointman onto a siding, where despite the best efforts of the engine driver, it collided with a number of stationary coal wagons.

Seven persons on the passenger train were killed and several injured. As one of the 24 members of the “highly respectable jury” assembled to examine the evidence, Eli would have taken part in the deliberations that recommended a charge of manslaughter against the pointman who had placed the train upon its fateful trajectory.

Eli is named as a farmer in the 1847 Post Office trade directory, but his farm is not (as was the routine in directories) named. The 1851 census places Eli and his younger brother Thomas “near the green”; not the most helpful piece of information, though it must surely mean The Mead or Grange Farm. The census provides the information that Eli was farming 363 acres employing seven labourers; very close to the 357 acres associated to him on the 1840 tithe map. It does not however help us understand who was occupying The Mead and who was in the farmhouse. Perhaps Eli was occupying one and Thomas the other.

The Musson & Craven´s trade directory of 1853 simply records that Eli is a farmer in the parish, and the census records of 1861 and 1871 are no more illuminating, placing Eli at the “Green." Perhaps Eli was at The Mead, and The Grange Farm was occupied at this time by agricultural workers in the employ of Eli. As for Wood End Farm, it looks very much as if the farmstead, known more commonly at the time as Wood House, was occupied throughout the 1840s to 1870s by a succession of agricultural labourers.

Eli is included in the 1876 Harrod and co trade directory of the parish, but yet again, the farm is unnamed, and even the sales notices published after his death on April 8th, 1877, fail to mention his residence by name. So, in fact, at no point during the Elkin’s tenancy is the name “Green Farm” ever explicitly associated with the family, though quite clearly it was.

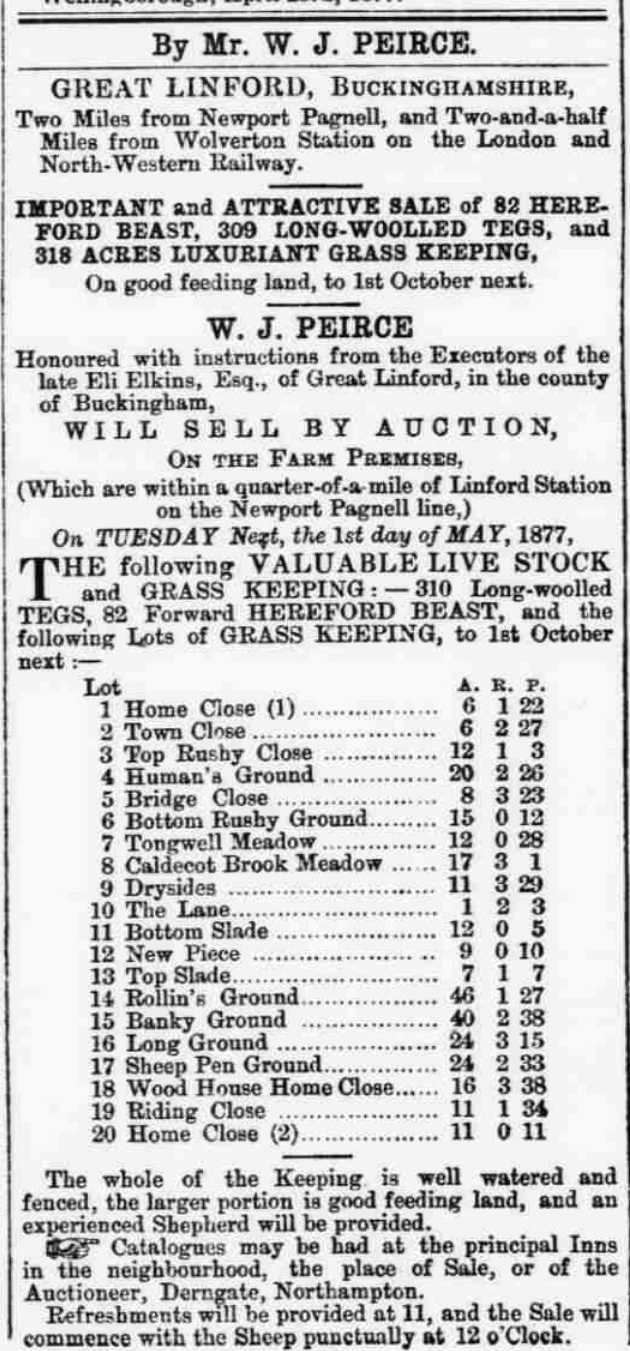

Eli died on April 6th, 1877, at the age of 76, prompting a flurry of sale notices in local newspapers that provide an intriguing insight into the nature of the farming he was carrying out and his lifestyle as a gentleman farmer. The Bucks Herald of April 28th, 1877, provides a wealth of information on the farm, including a list of livestock to be sold, the names of some of his fields, totalling 318 acres and the information that the farm is within a quarter of a mile of Great Linford Station. The later might be interpreted as the auctioneer’s exaggeration, as the farmstead is closer (as the crow flies) to a half mile from the station.

The census does however provide some useful information. In the same household at Great Linford in 1841 is Eli’s younger brother Thomas, both siblings described as farmers. Also present is 33-year-old Martha Thorpe, born 1808 at Preston Bissett, and whom we find mentioned in connection to an award made in 1842 by the Newport Pagnell Agricultural Association. The Northampton Mercury of October 1st reports that she received 30 shillings in recognition that she had been in Eli’s employ for seven years. Eli never married, but Martha was a constant in his life, and we can perhaps infer a close connection between the two, as she remained his housekeeper until his death. She herself never married, and her gravestone in St. Andrew’s churchyard states she, “was for above forty years the valued and respected housekeeper of Mr Elkins.”

Several other members of the extended Elkins family are present on the 1841 census, including William Pratt, who had married Leah Elkins in 1825, though the marriage was to prove tragically short lived, Leah having passed away shortly afterward. But William must have had an eye for the Elkins girls, as he wasted no time in wooing Leah’s 18-year-old younger sister Eliza, the pair marrying at St. Andrew Holborn in London on December 28th, 1826. The venue seems odd; perhaps there were some local quibbles with the propriety of the marriage, though the record states that the union had the consent of Joseph Elkins. By the time of the 1841 census, the couple had at least one child, Catherine, with mother and daughter both at the Great Linford farmstead.

Another of Joseph’s married daughters, 28-year-old Amelia is also present. She had married John Heygate on May 7th, 1839, at St. Andrews, Great Linford, though the couple made their home in Elkington, Northamptonshire, where they raised a family; indeed, on the night of the 1841 census, John was at Elkington with their baby daughter Mary.

Alongside his duties as a guardian, and as someone with sufficient income to qualify, Eli could also expect to be called upon to serve as a juror, and this was the case regarding one particularly important coroner’s inquest held in June 1847. On the night of Saturday June 5th, at approximately 10.45pm, the regularly scheduled train from Euston Square to Liverpool was approaching Wolverton, but due to human error, rather than make its appointed stop at the station, the train was redirected by the pointman onto a siding, where despite the best efforts of the engine driver, it collided with a number of stationary coal wagons.

Seven persons on the passenger train were killed and several injured. As one of the 24 members of the “highly respectable jury” assembled to examine the evidence, Eli would have taken part in the deliberations that recommended a charge of manslaughter against the pointman who had placed the train upon its fateful trajectory.

Eli is named as a farmer in the 1847 Post Office trade directory, but his farm is not (as was the routine in directories) named. The 1851 census places Eli and his younger brother Thomas “near the green”; not the most helpful piece of information, though it must surely mean The Mead or Grange Farm. The census provides the information that Eli was farming 363 acres employing seven labourers; very close to the 357 acres associated to him on the 1840 tithe map. It does not however help us understand who was occupying The Mead and who was in the farmhouse. Perhaps Eli was occupying one and Thomas the other.

The Musson & Craven´s trade directory of 1853 simply records that Eli is a farmer in the parish, and the census records of 1861 and 1871 are no more illuminating, placing Eli at the “Green." Perhaps Eli was at The Mead, and The Grange Farm was occupied at this time by agricultural workers in the employ of Eli. As for Wood End Farm, it looks very much as if the farmstead, known more commonly at the time as Wood House, was occupied throughout the 1840s to 1870s by a succession of agricultural labourers.

Eli is included in the 1876 Harrod and co trade directory of the parish, but yet again, the farm is unnamed, and even the sales notices published after his death on April 8th, 1877, fail to mention his residence by name. So, in fact, at no point during the Elkin’s tenancy is the name “Green Farm” ever explicitly associated with the family, though quite clearly it was.

Eli died on April 6th, 1877, at the age of 76, prompting a flurry of sale notices in local newspapers that provide an intriguing insight into the nature of the farming he was carrying out and his lifestyle as a gentleman farmer. The Bucks Herald of April 28th, 1877, provides a wealth of information on the farm, including a list of livestock to be sold, the names of some of his fields, totalling 318 acres and the information that the farm is within a quarter of a mile of Great Linford Station. The later might be interpreted as the auctioneer’s exaggeration, as the farmstead is closer (as the crow flies) to a half mile from the station.

The field names provided in the sale notice are particularly interesting; not all match those listed on the 1840 tithe map, but enough do that we can draw some conclusions. Notably, there are three fields named “Home Close”, implying that on his passing Eli had still counted a trio of distinct farmsteads within his purview. That one of these fields is named “Wood House Home Close” strongly points to one of these being Wood End Farm, a theory all but assured by the additional matching of two field names to the 1840 tithe map, Long Ground and Sheep Pen Ground. That Eli was also farming the land associated in 1840 with Grange Farm is also incontrovertible, as we can match a number of fields to the 1840 tithe map, Tongwell Meadow, Caldecot Brock Meadow and Drysides.

The same notice offered for sale 310 long wooled Tegs and 82 forward Hereford Beast. The former is a term for a young sheep between the January after its birth and its first two teeth, usually at 18 months. The “Beast” on offer are cattle, with the term “forward” likely meaning in this case that they are well grown and ready for the butcher.

It should be noted that the fields were not for sale, as a tenant farmer, they were not Eli’s to sell. Instead, he was offering the “grass keeping to 1st October next” to his fellow farmers for the gazing of their livestock. A sale of crops reported in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of August 4th, 1877, tells us that Eli had been growing wheat, barley and beans.

Another sale was advertised in the Northampton Mercury of September 22nd, this time focusing on Eli’s agricultural implements and machinery. Included in the extensive number of lots were an array of fascinating items, such as a scuffler, two boarded beast cribs, an oil-cake breaker and a tedding machine. More familiar sounding items included a combined mower and reaper, two iron pig troughs and a plough.

We also learn from a report carried in Croydon's Weekly Standard of October 13th, 1877, that Eli had been a prominent member of the local branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society, an organisation concerned with the dissemination of scripture to the poor of the country, and further afield in translation.

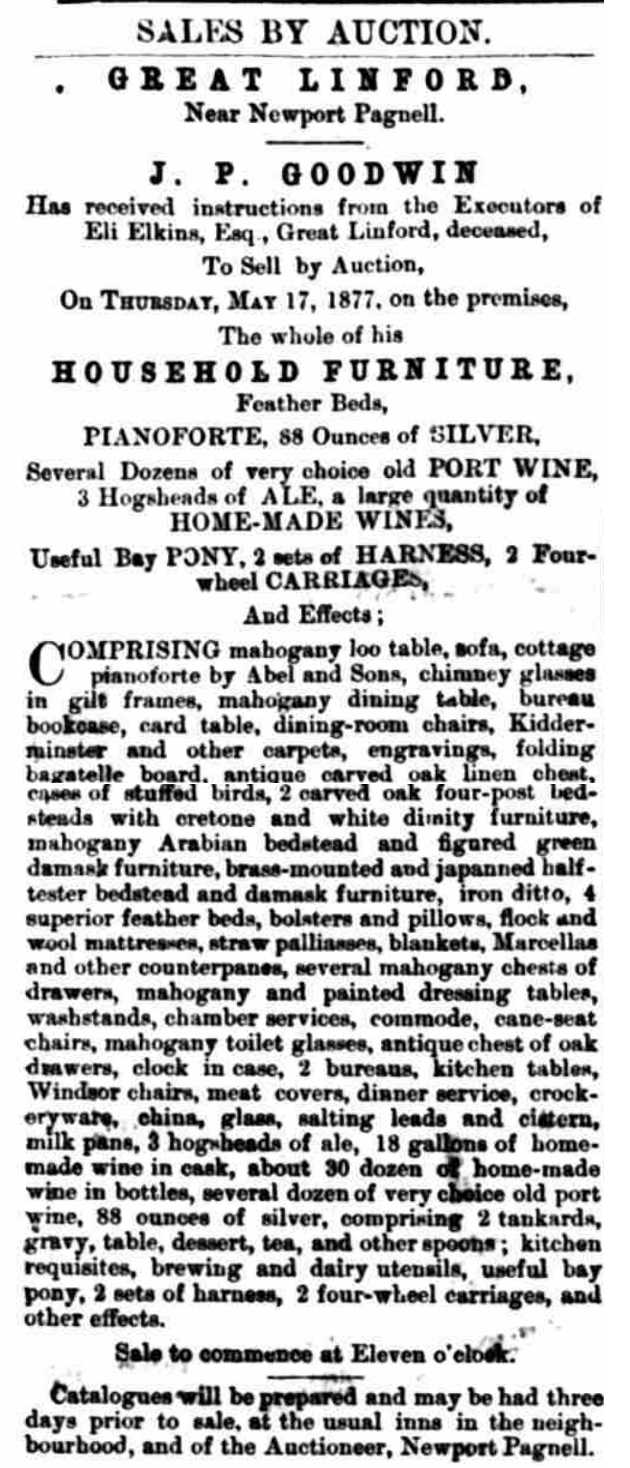

But it is an extensive inventory of his worldly goods offered for sale by auction (Croydon's Weekly Standard of May 12th, 1877) that provides the most illuminating insight into Eli’s life, painting a vivid picture of his relative wealth and living standards. Eli had amassed a significant collection of possessions, including 88 ouches of silver, comprising two tankards, plus gravy, table, dessert, tea and other spoons. The sale notice also reveals details such that he was home brewing both beer and wine, slept in an “Arabian” four poster bed and owned a Pianoforte (Piano) that had been purchased from the Northampton musical emporium, Abel and Sons.

The same notice offered for sale 310 long wooled Tegs and 82 forward Hereford Beast. The former is a term for a young sheep between the January after its birth and its first two teeth, usually at 18 months. The “Beast” on offer are cattle, with the term “forward” likely meaning in this case that they are well grown and ready for the butcher.

It should be noted that the fields were not for sale, as a tenant farmer, they were not Eli’s to sell. Instead, he was offering the “grass keeping to 1st October next” to his fellow farmers for the gazing of their livestock. A sale of crops reported in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of August 4th, 1877, tells us that Eli had been growing wheat, barley and beans.

Another sale was advertised in the Northampton Mercury of September 22nd, this time focusing on Eli’s agricultural implements and machinery. Included in the extensive number of lots were an array of fascinating items, such as a scuffler, two boarded beast cribs, an oil-cake breaker and a tedding machine. More familiar sounding items included a combined mower and reaper, two iron pig troughs and a plough.

We also learn from a report carried in Croydon's Weekly Standard of October 13th, 1877, that Eli had been a prominent member of the local branch of the British and Foreign Bible Society, an organisation concerned with the dissemination of scripture to the poor of the country, and further afield in translation.

But it is an extensive inventory of his worldly goods offered for sale by auction (Croydon's Weekly Standard of May 12th, 1877) that provides the most illuminating insight into Eli’s life, painting a vivid picture of his relative wealth and living standards. Eli had amassed a significant collection of possessions, including 88 ouches of silver, comprising two tankards, plus gravy, table, dessert, tea and other spoons. The sale notice also reveals details such that he was home brewing both beer and wine, slept in an “Arabian” four poster bed and owned a Pianoforte (Piano) that had been purchased from the Northampton musical emporium, Abel and Sons.

John Thomas Dover

The death of Eli spelt the end of the family’s time as farmers at Great Linford. Eli’s brother Thomas had died on September 20th, 1866, and as neither had married and lacking further children to carry on the business, the farm needed a new tenant. Whilst we cannot prove with certainty who was next to take over immediately afterward, a John Thomas Dover is a strong candidate.

Kelly's trade directories were issued in 1877 and 1883 but make no mention of a John Dover in the parish, however proving that these directories should not be relied upon as an infallible source of information, we can confirm John’s presence in the parish as he makes several appearances in newspapers during this period, though frustratingly the name of his farm goes unobserved.

John placed a help wanted ad in the Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette on April 2nd, 1878, seeking a cowman. The ad offers that the successful applicant will have a cottage to live in, with a good garden. Notably however, applicants are asked to apply to John at either Toddington in Bedfordshire, or Great Linford, perhaps implying that he was in the middle of moving or dividing his time between the two.

Children’s education generally ended when they were 10 at this time, and they were then expected to find gainful employment, though the rules were not always followed. The Bedfordshire Mercury of August 30th, 1879, under a headline of “A warning to farmers” reports that John was charged and fined 10 shillings plus costs in August that year for employing a 10-year-old boy (other accounts say 13-year-old) named Morgan Mapley in contravention of the Education Act, the boy not having obtained his certificate of proficiency, which is to say he had not obtained the mandatory educational standard expected at the time.

The 1881 census records that John Dover was resident at “The Green", consistent at least with the address given for previous tenants of the farm. Rather more usefully it states that he was a farmer of 384 acres employing four men and three boys. Finally, though, a document can be found that explicitly names and places "Green Farm" in the parish; the 1881 Ordnance Survey map. By contrast, the house now known as The Mead is unlabelled, and it remains unclear what connection, if any, there was between the two. Click here to view the 1881 Ordnance Survey map of Great Linford.

The census of 1881 tells us that John Dover was born circa 1856 in Toddington in Bedfordshire. We can discover from this that he belonged to an established farming family. 25-year-old John had not yet married, and nor had his 23-year-old sister Mary Louisa, who was also present in the household and described as a housekeeper. Another sister, Rosa, aged 20, was visiting, as was his six-year-old brother, Harry. Rounding out the household were two servants and a boarder.

Farming was a dangerous business, as the following story of a fatal accident (Bucks Herald, September 3rd, 1881) sadly demonstrates. Early on the morning of September 2nd, George Pallett, an employee of John Dover, was assisting in bringing three empty carts from Newport Pagnell to Great Linford. In his testimony to a coroner’s jury, Samuel Townsend, a horse keeper also in the employ of John Dover, described what happened. On the way to Great Linford, they met some carts coming the other way, and for reasons unknown, George’s horse was spooked. This caused George to lose his footing and fall beneath the wheel of a cart, which passed over him.

Poor George lingered for a few hours, but his lung had been punctured by a broken rib, and he died at home just after eleven o’clock the same evening as the accident. With little or no deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of accidental death. Despite wide publicity on the case in local newspapers, there are no reported remarks from the coroner on lessons to be learned, or recommended measures to prevent similar tragedies. 57-year-old George’s death is just a statistic, and it is only by consulting the census records that we know he left a wife and 14-year-old daughter.

There was little in the way of steady work for agricultural workers, and much would have been on an ad-hoc basis, such as the case of George Hillyer of Newport Pagnell, whom John contracted in 1885 to do thirteen chains (an old measure equating to around 20 metres) of hedge cutting and ditching at two shillings, two pence per chain. Unfortunately, John felt compelled to bring George before the petty sessions of June 24th, accusing him of, “absenting himself from his employ without giving proper notice.” In a report of the case published in the North Bucks Times and County Observer of July 2nd, John told the bench that he had no wish to press the case but was obliged to make the point to George that he could not break a contract as he pleased. We know nothing of the circumstances that caused George to absent himself, but he was ordered to complete the work, pay costs and was fined £1. As a footnote to this story, George was back in court the following year, having failed to obey the judgement, but we are left no clearer as to why the dispute had festered, though John offered to take 10 shillings to settle the matter.

John seems to have been a farmer of some talent, frequently reported as winning various animal husbandry awards. He took two second place prizes at the Christmas Fat Stock Market of December 1883, for his Tegs (two-year-old sheep) and continued year on year to win prizes at the Christmas show, though rearing livestock was also not without its risks. Illustrating the dangers posed by disease to farmer’s livelihoods, in 1883 foot and mouth was reported at John’s farm, with eight of his cattle afflicted.

John also had some clear expertise in equine matters, as his horse Happy Jack took first prize in a jumping competition at the Bedfordshire Agricultural Show in July 1887. Happy Jack was also on winning form at the Northwest Bucks Agricultural Show in September the same year, with the Buckingham Express of September 17th, reporting that the grey horse of sterling worth, “jumped in good style, taking everything in splendid form, clearing all the fences as though he liked the fun of it, being very cleverly handled by his jockey who was lustily cheered.” The horse was variously described as ridden by a J. T. Dover or Mr Dover Jnr, but the relationship to John Thomas Dover remains unclear; he cannot as expected be yet identified as his son. Another of John’s horses, named The Clown, and described as a “remarkably clever fencer”, took first prize in the jumping competition at the Gloucestershire Agricultural Show in July 1888.

In 1887, a barn was raised on what is now Harpers Lane by William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt, as evidenced by the date stone installed in the wall that bears his initials. This is on the opposite side of the lane to Grange Farm, and rather closer to the house known as The Mead.

Kelly's trade directories were issued in 1877 and 1883 but make no mention of a John Dover in the parish, however proving that these directories should not be relied upon as an infallible source of information, we can confirm John’s presence in the parish as he makes several appearances in newspapers during this period, though frustratingly the name of his farm goes unobserved.

John placed a help wanted ad in the Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette on April 2nd, 1878, seeking a cowman. The ad offers that the successful applicant will have a cottage to live in, with a good garden. Notably however, applicants are asked to apply to John at either Toddington in Bedfordshire, or Great Linford, perhaps implying that he was in the middle of moving or dividing his time between the two.

Children’s education generally ended when they were 10 at this time, and they were then expected to find gainful employment, though the rules were not always followed. The Bedfordshire Mercury of August 30th, 1879, under a headline of “A warning to farmers” reports that John was charged and fined 10 shillings plus costs in August that year for employing a 10-year-old boy (other accounts say 13-year-old) named Morgan Mapley in contravention of the Education Act, the boy not having obtained his certificate of proficiency, which is to say he had not obtained the mandatory educational standard expected at the time.

The 1881 census records that John Dover was resident at “The Green", consistent at least with the address given for previous tenants of the farm. Rather more usefully it states that he was a farmer of 384 acres employing four men and three boys. Finally, though, a document can be found that explicitly names and places "Green Farm" in the parish; the 1881 Ordnance Survey map. By contrast, the house now known as The Mead is unlabelled, and it remains unclear what connection, if any, there was between the two. Click here to view the 1881 Ordnance Survey map of Great Linford.

The census of 1881 tells us that John Dover was born circa 1856 in Toddington in Bedfordshire. We can discover from this that he belonged to an established farming family. 25-year-old John had not yet married, and nor had his 23-year-old sister Mary Louisa, who was also present in the household and described as a housekeeper. Another sister, Rosa, aged 20, was visiting, as was his six-year-old brother, Harry. Rounding out the household were two servants and a boarder.

Farming was a dangerous business, as the following story of a fatal accident (Bucks Herald, September 3rd, 1881) sadly demonstrates. Early on the morning of September 2nd, George Pallett, an employee of John Dover, was assisting in bringing three empty carts from Newport Pagnell to Great Linford. In his testimony to a coroner’s jury, Samuel Townsend, a horse keeper also in the employ of John Dover, described what happened. On the way to Great Linford, they met some carts coming the other way, and for reasons unknown, George’s horse was spooked. This caused George to lose his footing and fall beneath the wheel of a cart, which passed over him.

Poor George lingered for a few hours, but his lung had been punctured by a broken rib, and he died at home just after eleven o’clock the same evening as the accident. With little or no deliberation, the jury returned a verdict of accidental death. Despite wide publicity on the case in local newspapers, there are no reported remarks from the coroner on lessons to be learned, or recommended measures to prevent similar tragedies. 57-year-old George’s death is just a statistic, and it is only by consulting the census records that we know he left a wife and 14-year-old daughter.

There was little in the way of steady work for agricultural workers, and much would have been on an ad-hoc basis, such as the case of George Hillyer of Newport Pagnell, whom John contracted in 1885 to do thirteen chains (an old measure equating to around 20 metres) of hedge cutting and ditching at two shillings, two pence per chain. Unfortunately, John felt compelled to bring George before the petty sessions of June 24th, accusing him of, “absenting himself from his employ without giving proper notice.” In a report of the case published in the North Bucks Times and County Observer of July 2nd, John told the bench that he had no wish to press the case but was obliged to make the point to George that he could not break a contract as he pleased. We know nothing of the circumstances that caused George to absent himself, but he was ordered to complete the work, pay costs and was fined £1. As a footnote to this story, George was back in court the following year, having failed to obey the judgement, but we are left no clearer as to why the dispute had festered, though John offered to take 10 shillings to settle the matter.

John seems to have been a farmer of some talent, frequently reported as winning various animal husbandry awards. He took two second place prizes at the Christmas Fat Stock Market of December 1883, for his Tegs (two-year-old sheep) and continued year on year to win prizes at the Christmas show, though rearing livestock was also not without its risks. Illustrating the dangers posed by disease to farmer’s livelihoods, in 1883 foot and mouth was reported at John’s farm, with eight of his cattle afflicted.

John also had some clear expertise in equine matters, as his horse Happy Jack took first prize in a jumping competition at the Bedfordshire Agricultural Show in July 1887. Happy Jack was also on winning form at the Northwest Bucks Agricultural Show in September the same year, with the Buckingham Express of September 17th, reporting that the grey horse of sterling worth, “jumped in good style, taking everything in splendid form, clearing all the fences as though he liked the fun of it, being very cleverly handled by his jockey who was lustily cheered.” The horse was variously described as ridden by a J. T. Dover or Mr Dover Jnr, but the relationship to John Thomas Dover remains unclear; he cannot as expected be yet identified as his son. Another of John’s horses, named The Clown, and described as a “remarkably clever fencer”, took first prize in the jumping competition at the Gloucestershire Agricultural Show in July 1888.

In 1887, a barn was raised on what is now Harpers Lane by William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt, as evidenced by the date stone installed in the wall that bears his initials. This is on the opposite side of the lane to Grange Farm, and rather closer to the house known as The Mead.

The Kelly’s trade directory edition of 1887 finally names John Dover as a farmer in the parish, though omits (as we have come to expect) the name of the farm. John was a prominent member of the local Conservative Association, he is for instance mentioned in his capacity as a member attending a raucous meeting in the village on August 6th, 1885. Under the headline “The tables turned on the Conservatives at Great Linford” (Oxfordshire Telegraph, August 12th) we learn that Sir Samuel Wilson, the Conservative candidate for the Bucks Northern Division, was given a less than cordial welcome in the village.

Later that same year, John was also sworn in as a grand jury member at the Bucks Michaelmas Quarter Sessions, further illustrating that farmers occupied a higher position in society than most. As a final illustration of John’s status within the village, he took a prominent role in the Queen’s Jubilee celebrations of June 1887 and a passing reference to his participation (Croydon's Weekly Standard, June 25th, 1887) also alludes to the fact that he was a churchwarden.

As is usually the case in exploring the history of people and places at this time, the contributions of women are frequently relegated to footnotes, but we do have several references to a Mrs Dover in the village at this time, whom we can presume to be a relative. On the occasion of a Bazaar held in the Rectory grounds on August 13th, 1884, Mrs Dover (supported by an unnamed sister) was responsible for one of the stalls, rubbing shoulders with Mrs Uthwatt, who had the adjacent stall. Mrs Dover is mentioned again, this time in connection to a concert held in aid of the church choir in December 1886, but neither article provides any clue as to the relationship of these women to John Dover. All indications are that he did not marry until 1889, to an Elizabeth Fairy, so perhaps Mrs Dover was his mother, Elizabeth; we do not have any record that places her at Great Linford, but conceivably she and a sister were visiting or had come to live with him.

We know that John Dover left Green Farm in 1888 as a number of sale notices were published that year, disposing of livestock and crops. Included were 281 Oxfordshire Down Sheep, a breed usually reared for meat. Additionally, there were “84 fat wethers and theaves”, the former been castrated male sheep and the latter usually a ewe older than 12 months but younger than 24 months.

On his departure John moved to Milton Keynes village and the Uthwatts began the task of finding a new tenant, though it is interesting to note that affairs were being managed by the widowed Anna Maria Uthwatt. In an advertisement carried in a number of newspapers across the country, including the York Herald of March 2nd, 1888, the Green Farm is offered for rent at £600 per annum, with emphasis given to the daily delivery of milk to London by train, demonstrating the importance of this growing market to rural areas. It is also noteworthy that the Uthwatts were casting the net so widely in search of a new tenant.

Later that same year, John was also sworn in as a grand jury member at the Bucks Michaelmas Quarter Sessions, further illustrating that farmers occupied a higher position in society than most. As a final illustration of John’s status within the village, he took a prominent role in the Queen’s Jubilee celebrations of June 1887 and a passing reference to his participation (Croydon's Weekly Standard, June 25th, 1887) also alludes to the fact that he was a churchwarden.

As is usually the case in exploring the history of people and places at this time, the contributions of women are frequently relegated to footnotes, but we do have several references to a Mrs Dover in the village at this time, whom we can presume to be a relative. On the occasion of a Bazaar held in the Rectory grounds on August 13th, 1884, Mrs Dover (supported by an unnamed sister) was responsible for one of the stalls, rubbing shoulders with Mrs Uthwatt, who had the adjacent stall. Mrs Dover is mentioned again, this time in connection to a concert held in aid of the church choir in December 1886, but neither article provides any clue as to the relationship of these women to John Dover. All indications are that he did not marry until 1889, to an Elizabeth Fairy, so perhaps Mrs Dover was his mother, Elizabeth; we do not have any record that places her at Great Linford, but conceivably she and a sister were visiting or had come to live with him.

We know that John Dover left Green Farm in 1888 as a number of sale notices were published that year, disposing of livestock and crops. Included were 281 Oxfordshire Down Sheep, a breed usually reared for meat. Additionally, there were “84 fat wethers and theaves”, the former been castrated male sheep and the latter usually a ewe older than 12 months but younger than 24 months.

On his departure John moved to Milton Keynes village and the Uthwatts began the task of finding a new tenant, though it is interesting to note that affairs were being managed by the widowed Anna Maria Uthwatt. In an advertisement carried in a number of newspapers across the country, including the York Herald of March 2nd, 1888, the Green Farm is offered for rent at £600 per annum, with emphasis given to the daily delivery of milk to London by train, demonstrating the importance of this growing market to rural areas. It is also noteworthy that the Uthwatts were casting the net so widely in search of a new tenant.

John Taylor

We can be certain that the farm was next let to a John Taylor, as reference to the transfer can be found in the pages of a valuation book (Buckinghamshire County Archives (D-WIG/2/1/19) kept by George Wigley, the owner of a firm of chartered surveyors, auctioneers and estate agents, whose offices were in Winslow. George visited “Green Farm” on November 23rd, 1888, where he appraised the value of a number of items, including a 21-ton rick of hay, a chaff cutter and a grist mill, the valuation coming to a grand total of £196 and 15 shillings.

The 1891 Kelly’s trade directory records John Taylor in the parish, with his presence confirmed at “The Green Farm” in the 1891 census; the first time a census explicitly names the farm. Living alongside him is his sister Louisa and a servant, Amelia Nicholls. Unfortunately, either John was not forthcoming with his place of birth, or the enumerator was dilatory, as the census records only that he and his sister were born in Buckinghamshire. As the names are not particularly uncommon, it is not at present possible to narrow down who the Taylors were, or where they hailed from, or for that matter, where they went next.

Information about John is in fact rather thin on the ground with only passing references appearing in newspapers, such that he was present at a Conservative Association dinner at the school in early 1894, and notably was one of the five men elected to serve on the very first parish council for Great Linford in December the same year.

The Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette of Tuesday June 11th, 1895, indicates that his tenure at the farm was to be a short one, as the Green Farm was to be let at Michaelmas next, which would be September 29th. The notice does provide a useful description of the farm; that it comprised upwards of 260 acres, of which 216 were "first rate meadow and pasture", and the remainder arable. There were two good cottages, a comfortable house and ample outbuildings, principally of good modern construction.

The 1891 Kelly’s trade directory records John Taylor in the parish, with his presence confirmed at “The Green Farm” in the 1891 census; the first time a census explicitly names the farm. Living alongside him is his sister Louisa and a servant, Amelia Nicholls. Unfortunately, either John was not forthcoming with his place of birth, or the enumerator was dilatory, as the census records only that he and his sister were born in Buckinghamshire. As the names are not particularly uncommon, it is not at present possible to narrow down who the Taylors were, or where they hailed from, or for that matter, where they went next.

Information about John is in fact rather thin on the ground with only passing references appearing in newspapers, such that he was present at a Conservative Association dinner at the school in early 1894, and notably was one of the five men elected to serve on the very first parish council for Great Linford in December the same year.

The Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette of Tuesday June 11th, 1895, indicates that his tenure at the farm was to be a short one, as the Green Farm was to be let at Michaelmas next, which would be September 29th. The notice does provide a useful description of the farm; that it comprised upwards of 260 acres, of which 216 were "first rate meadow and pasture", and the remainder arable. There were two good cottages, a comfortable house and ample outbuildings, principally of good modern construction.

William Brice Shakeshaft

The next available trade directory, published by Kelly’s in 1899, confirms the absence of John Taylor, but includes a new farmer in the village, William Brice Shakeshaft. Once again, the directory omits the name of his farm, but the 1901 census is more forthcoming, and for the first time the name of Grange Farm is given, though as we will see, the name took a while to stick. Recorded on the census are William, his wife Emma, sons William and John, and daughter Marguerite. Also present is a servant, Alice Keech.

William Brice Shakeshaft was born in Ravenstone in Buckinghamshire on March 16th, 1857. His father Thomas was himself a farmer, and had worked land at Ravenstone, as had his father before him, and as subsequently would William. William had married Emma Tomason at Ridgemont, Bedfordshire on October 2nd, 1879, and the couple went on to have at least five children between 1880 and 1890, all at Ravenstone. William was active from at least the mid-1880s as a member of the board of the Newport Pagnell guardians as a surveyor, responsible for such things as the upkeep of roads, and circa 1891, the family had relocated to the quaint sounding Kickles Farm at Newport Pagnell. Around the mid-1890s, William appears to have made the move to Great Linford.

The 1900 O.S map for the parish continues to name the farmstead Green Farm, though William was otherwise engaged in this period, as he appears to have served in the second Boar war (1899-1902.) His name is included in a list of recipients for a war medal carried in the Buckingham Express dated August 3rd, 1901. He must have been back from service before March 31st that year, which was the day the census was conducted.

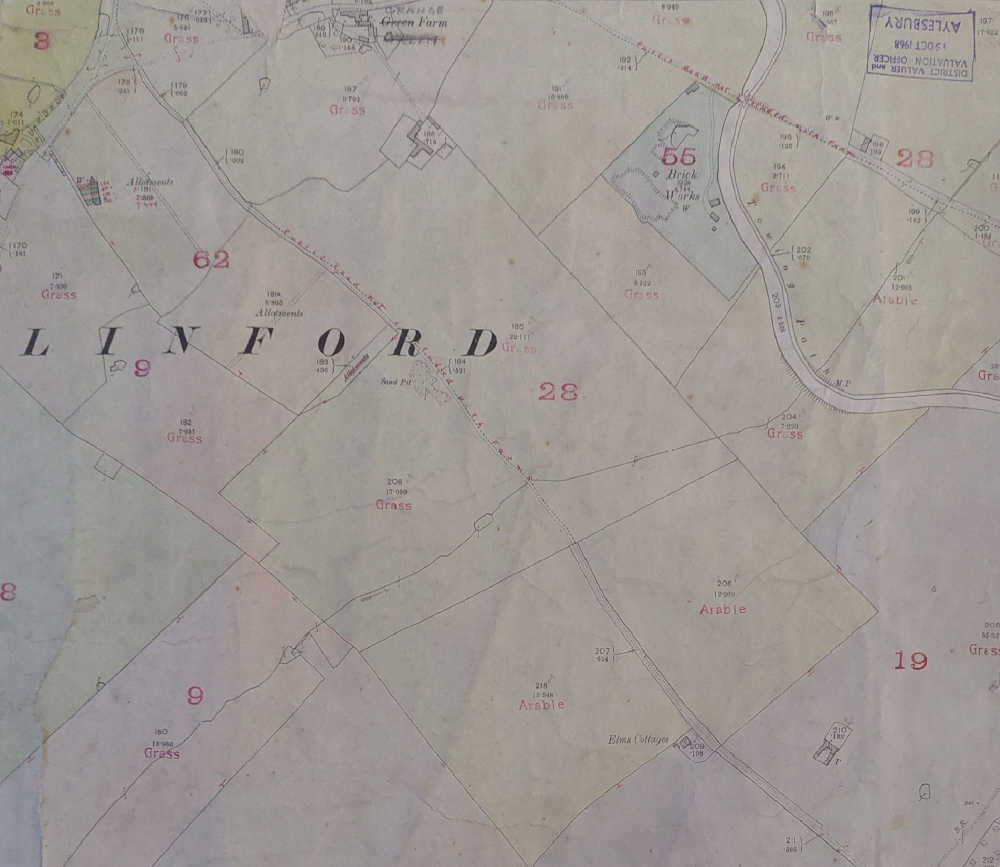

The 1910 valuation office survey map for the village (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5) lists William Brice Shakeshaft as the occupant of a dwelling named as "The Grange" along with a "Grange Farm" of 256 acres, plus buildings, the whole with a rateable value of £204 and 15 shillings. As the survey utilises an earlier O.S map, the valuer has crossed out Green Farm and handwritten in Grange Farm. The map employs a colour coding for each farm's land, a pale green for Grange Farm with the all the associated fields assigned the identifying number 28. The farm straddles two individual tithe maps, extracts of which are reproduced below. The join between the two maps is not a smooth one, but it is clear that The Mead is encompassed within the land assigned to Grange Farm.

William Brice Shakeshaft was born in Ravenstone in Buckinghamshire on March 16th, 1857. His father Thomas was himself a farmer, and had worked land at Ravenstone, as had his father before him, and as subsequently would William. William had married Emma Tomason at Ridgemont, Bedfordshire on October 2nd, 1879, and the couple went on to have at least five children between 1880 and 1890, all at Ravenstone. William was active from at least the mid-1880s as a member of the board of the Newport Pagnell guardians as a surveyor, responsible for such things as the upkeep of roads, and circa 1891, the family had relocated to the quaint sounding Kickles Farm at Newport Pagnell. Around the mid-1890s, William appears to have made the move to Great Linford.

The 1900 O.S map for the parish continues to name the farmstead Green Farm, though William was otherwise engaged in this period, as he appears to have served in the second Boar war (1899-1902.) His name is included in a list of recipients for a war medal carried in the Buckingham Express dated August 3rd, 1901. He must have been back from service before March 31st that year, which was the day the census was conducted.

The 1910 valuation office survey map for the village (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5) lists William Brice Shakeshaft as the occupant of a dwelling named as "The Grange" along with a "Grange Farm" of 256 acres, plus buildings, the whole with a rateable value of £204 and 15 shillings. As the survey utilises an earlier O.S map, the valuer has crossed out Green Farm and handwritten in Grange Farm. The map employs a colour coding for each farm's land, a pale green for Grange Farm with the all the associated fields assigned the identifying number 28. The farm straddles two individual tithe maps, extracts of which are reproduced below. The join between the two maps is not a smooth one, but it is clear that The Mead is encompassed within the land assigned to Grange Farm.

The 1911 census was the first filled out by the respondent rather than a visiting enumerator, and for reasons of his own William decided to stick with the name Green Farm. Why there was this apparent confusion as to name of the farm is unclear, and indeed we do not know why it was ever changed at all. Grange means a country house with farm buildings attached, or an outlying farm with tithe barns, belonging to a monastery or feudal lord, so on that basis, might this have been sufficient motivation for the Uthwatts to want to change the name to something grander? Perhaps William Shakeshaft was having none of it. Interestingly, on the 1911 census, William describes himself as a “farmer and valuer”, though what he was valuing remains unclear and he is described solely as a farmer on other documents.

The 1911 census was conducted on the night of Sunday April 2nd, but by the time the Kelly’s directory of that same year was published, William Shakeshaft had departed the farm. The Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette of October 31st, 1939, provides an interesting postscript to the story, noting that William and Emma had just celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary. William was then 82, and living and farming at Wavendon, but the article provides some additional details on his life and interests.

The 1911 census was conducted on the night of Sunday April 2nd, but by the time the Kelly’s directory of that same year was published, William Shakeshaft had departed the farm. The Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette of October 31st, 1939, provides an interesting postscript to the story, noting that William and Emma had just celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary. William was then 82, and living and farming at Wavendon, but the article provides some additional details on his life and interests.

Mr. Shakeshaft was a member of the Newport Pagnell Board of Guardians and the Rural District Council. He was the chief founder of the Newport Pagnell Shire Horse Society and for 31 years served the Society as Hon. Secretary. In 1925, in appreciation of all he had done for shire horse breeding, the Society presented him with a silver salver. He was also one of the pioneers of the National Farmers' Union in Buckinghamshire, and was Hon. Secretary of the Newport Pagnell Branch for a long time. In his younger days Mr. Shackeshaft often enjoyed a run with the Whaddon. Grafton and Oakley Hunts. He competed in many pigeon shooting matches in this and the neighbouring counties 40 years ago, and was always high up in the prize list.

The article mentions also that one son had died in WW1 at Cambrai in France, (we can identify this as John) and that another son had died in Rhodesia, now modern-day Zimbabwe. Further investigation reveals the rather morbid details of the latter death. The person in question was William Brice Shakeshaft Jnr, and he had died in the city of Bulawayo in October 1913 at the age of 29. He had been stricken by enteric fever and succumbed to shock after one of his legs was amputated.

William Powell

Green Farm now had a new resident, William Powell, who had been born at Heath and Reach, Bedfordshire, in 1879. The 1911 Kelly’s directory places him at Green Farm, as does the edition for 1915, but war was about to intrude. The Wolverton Express of March 5th, 1915, reported that William Powell had been accepted for service with the Army Veterinary Corps, and that in his absence the farm would be supervised by, “agricultural friends in the village.” At present we cannot identify his rank or where he might have served, but he did return (hopefully unscathed) to the farm by at least 1918.

We know this as we can begin to make use of the new electoral rolls that were ushered in with voting reforms. William and his wife Evelyn Mary Reynolds Powell, nee James (born Stoke Bruerne, Northamptonshire in 1879) are listed together from 1918 through to 1921; they are also present for the 1921 census, with their four-year-old son James Herbert Ault Powell, who was born at Great Linford in 1917. Two servants, Annie and Kathleen Harcourt, both born at Lathbury, are also in the household. Kathleen is described as a nurse servant.

Sadly, Evelyn passed away on July 13th, 1922, aged only 44; her gravestone can still be seen in St. Andrew’s churchyard. William continued to be listed on the electoral rolls, and from 1930 his son John also appears, having attained the minimum voting age of 21. An Agnes Elizabeth Powell also appears sporadically from 1924, but the family relationship has yet to be ascertained.

The electoral rolls cement the name of the farm as Grange Farm, and we also glean some other interesting information from these documents, as they provide the names of persons residing at Grange Farm Cottages, which would have been homes provided for agricultural labourers working on the farm. Over a dozen people can be identified in the period 1918 to 1931, such as Thomas William Pack and his wife Gertrude, though Thomas frequently went by the name Jack in the electoral rolls. Whilst others came and went, Jack and Gertrude (known as Gerti) were a fixture at the farm; they are also to be found on the 1911 census, Jack described as working as a cowman on the farm.

Another interesting aspect of the electoral rolls is that they highlighted a person’s eligibility for jury duty, a role that William Powell fulfilled between 1922 and 1930. In fact, for several years he was denoted as a Special Juror. Not that there was likely to be anything special about him in terms of his knowledge or experience of legal matters, it simply meant that as a householder, his rateable value had been accessed at £50 or more. Prior to 1927 he had been an ordinary juror, accessed at £20, so we might infer that his fortunes had been increasing.

It seems that William did have a sense of right and wrong, as illustrated by a story published in the Northampton Mercury of June 22nd, 1923. Herbert Frederick Thompkins was an agricultural labour employed by William and had witnessed a farmhand named Ernest Atkinson in the employ of Mr Uthwatt kick a sheep several times. Herbert had examined the sheep and found it in distress, and upon returning to the field the following day, found it dead. He had then removed the carcass to the yard of Grange Farm, where William called for a vet to examine the body. Damningly, William testified that Ernest Atkinson had approached him the day before, and offered him £5 for his silence in the matter, to which entreaty William flatly replied, no. The chairman of the bench, having listened to further testimony, including from the vet and the accused, concluded that Atkinson had committed an act of gross cruelty, and fined him £5.

Another interesting case that provides an insight into William’s character but also the difficulties and hardships of rural life is reported in the Northampton Chronicle and Echo of August 12th, 1926. As testified by William Powell to the Newport Pagnell Petty Sessions, he had been on the public road that passed through his farm (we might presume Willen Lane, now known as Harper’s Lane) when he spied William John Taplin carrying some wood over his shoulder, which were subsequently to be identified as fence rails purloined from the farm. Taplin attempted to talk his way out of trouble, saying that, “I hope you don’t mind my going round your fields for some wood”, which William most certainly did, ordering Taplin to leave the wood in his yard. Powell further testified that he had no objection to people helping themselves to water from a spring on his farm, but the following morning noticed damaged fencing, the broken areas corresponding to the wood he had confiscated from Taplin.

Questioned on the matter, Taplin pled guilty, but offered the defence that he had taken the wood due to, “the present crisis”, which would be a reference to the general strike. Though largely over in June of 1926, the miners persevered for several more months, which would explain why Taplin told the bench he was unable to obtain fuel. “He had to find some wood and fetch some water before he could have his tea. His wife was unable to carry water or wood. He thought the rails were no use as they were in the ditch.”

Perhaps moved by Tompkin’s circumstances, William Powell declined to press the case, though expressed annoyance to the bench that his fences had been interfered with at the risk of his cattle straying. The bench were not quite so forgiving, and fined Tompkins a total of 17 shillings and six pence.

William was less inclined to leniency in January of 1930, when he caught four boys damaging one of his hayricks. He had lain in wait in Willen Lane for the boys, having suffered similar damage the previous week, and though they fled when challenged, he was able to waylay one of the boys, who turned in his fellows. Fines were issued and a warning issued of incarceration in a reformatory if they were brought before the bench again.

William was not entirely without sin himself, pleading guilty to driving a cart without two front lights in February of 1930. He offered as mitigation his ignorance of the law and that he had been using one lamp for years, causing the clerk to observe to laughter in the court that he had been lucky. The judge fined him five shillings.

William was clearly a man interested in the development of farming science, as evidenced by his involvement with the James Patent Tractor Plough company. William appears to have been one of the shareholders, and in a prospectus carried in the Bedfordshire Times and Independent of May 30th, 1919, made the following declaration.

We know this as we can begin to make use of the new electoral rolls that were ushered in with voting reforms. William and his wife Evelyn Mary Reynolds Powell, nee James (born Stoke Bruerne, Northamptonshire in 1879) are listed together from 1918 through to 1921; they are also present for the 1921 census, with their four-year-old son James Herbert Ault Powell, who was born at Great Linford in 1917. Two servants, Annie and Kathleen Harcourt, both born at Lathbury, are also in the household. Kathleen is described as a nurse servant.

Sadly, Evelyn passed away on July 13th, 1922, aged only 44; her gravestone can still be seen in St. Andrew’s churchyard. William continued to be listed on the electoral rolls, and from 1930 his son John also appears, having attained the minimum voting age of 21. An Agnes Elizabeth Powell also appears sporadically from 1924, but the family relationship has yet to be ascertained.

The electoral rolls cement the name of the farm as Grange Farm, and we also glean some other interesting information from these documents, as they provide the names of persons residing at Grange Farm Cottages, which would have been homes provided for agricultural labourers working on the farm. Over a dozen people can be identified in the period 1918 to 1931, such as Thomas William Pack and his wife Gertrude, though Thomas frequently went by the name Jack in the electoral rolls. Whilst others came and went, Jack and Gertrude (known as Gerti) were a fixture at the farm; they are also to be found on the 1911 census, Jack described as working as a cowman on the farm.

Another interesting aspect of the electoral rolls is that they highlighted a person’s eligibility for jury duty, a role that William Powell fulfilled between 1922 and 1930. In fact, for several years he was denoted as a Special Juror. Not that there was likely to be anything special about him in terms of his knowledge or experience of legal matters, it simply meant that as a householder, his rateable value had been accessed at £50 or more. Prior to 1927 he had been an ordinary juror, accessed at £20, so we might infer that his fortunes had been increasing.

It seems that William did have a sense of right and wrong, as illustrated by a story published in the Northampton Mercury of June 22nd, 1923. Herbert Frederick Thompkins was an agricultural labour employed by William and had witnessed a farmhand named Ernest Atkinson in the employ of Mr Uthwatt kick a sheep several times. Herbert had examined the sheep and found it in distress, and upon returning to the field the following day, found it dead. He had then removed the carcass to the yard of Grange Farm, where William called for a vet to examine the body. Damningly, William testified that Ernest Atkinson had approached him the day before, and offered him £5 for his silence in the matter, to which entreaty William flatly replied, no. The chairman of the bench, having listened to further testimony, including from the vet and the accused, concluded that Atkinson had committed an act of gross cruelty, and fined him £5.

Another interesting case that provides an insight into William’s character but also the difficulties and hardships of rural life is reported in the Northampton Chronicle and Echo of August 12th, 1926. As testified by William Powell to the Newport Pagnell Petty Sessions, he had been on the public road that passed through his farm (we might presume Willen Lane, now known as Harper’s Lane) when he spied William John Taplin carrying some wood over his shoulder, which were subsequently to be identified as fence rails purloined from the farm. Taplin attempted to talk his way out of trouble, saying that, “I hope you don’t mind my going round your fields for some wood”, which William most certainly did, ordering Taplin to leave the wood in his yard. Powell further testified that he had no objection to people helping themselves to water from a spring on his farm, but the following morning noticed damaged fencing, the broken areas corresponding to the wood he had confiscated from Taplin.

Questioned on the matter, Taplin pled guilty, but offered the defence that he had taken the wood due to, “the present crisis”, which would be a reference to the general strike. Though largely over in June of 1926, the miners persevered for several more months, which would explain why Taplin told the bench he was unable to obtain fuel. “He had to find some wood and fetch some water before he could have his tea. His wife was unable to carry water or wood. He thought the rails were no use as they were in the ditch.”

Perhaps moved by Tompkin’s circumstances, William Powell declined to press the case, though expressed annoyance to the bench that his fences had been interfered with at the risk of his cattle straying. The bench were not quite so forgiving, and fined Tompkins a total of 17 shillings and six pence.

William was less inclined to leniency in January of 1930, when he caught four boys damaging one of his hayricks. He had lain in wait in Willen Lane for the boys, having suffered similar damage the previous week, and though they fled when challenged, he was able to waylay one of the boys, who turned in his fellows. Fines were issued and a warning issued of incarceration in a reformatory if they were brought before the bench again.

William was not entirely without sin himself, pleading guilty to driving a cart without two front lights in February of 1930. He offered as mitigation his ignorance of the law and that he had been using one lamp for years, causing the clerk to observe to laughter in the court that he had been lucky. The judge fined him five shillings.

William was clearly a man interested in the development of farming science, as evidenced by his involvement with the James Patent Tractor Plough company. William appears to have been one of the shareholders, and in a prospectus carried in the Bedfordshire Times and Independent of May 30th, 1919, made the following declaration.

I have great pleasure in informing you that the James Patent Tractor Plough attached to the Whiting-Bull Tractor has done most excellent work on my farm at Great Linford. A double furrow plough was used in a 12 acre field of heavy three-horse land (after Barley) partly to a depth of five inches and partly to a depth of 7 inches. At each depth a clear even furrow was drawn. The plough worked steadily without enforced stoppages, and the only labour required was the driver. The land was ploughed at the rate 1½ acres per hour. I have no hesitation in testifying to the efficiency of the work done and the expeditious manner in which it was effected.

Little else can be found about this company, other than that the concept was to place the plough at the front of the tractor rather than draw it behind, but perhaps the most telling aspect of William’s testimonial is that he made a virtue of the fact that he needed only a driver to plough his field; a reduction in his wage bill that likely did not go unremarked upon by the agricultural labourers in his employ.

A notice in the Wolverton Express of September 2nd, 1932, announced a sale of livestock, farm equipment and some household furniture, as William Powell was retiring from farming. He was 53 at the time, and perhaps in ill health, as it was reported in the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of June 23rd, 1934, that he had passed away. The brief obituary stated:

A notice in the Wolverton Express of September 2nd, 1932, announced a sale of livestock, farm equipment and some household furniture, as William Powell was retiring from farming. He was 53 at the time, and perhaps in ill health, as it was reported in the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of June 23rd, 1934, that he had passed away. The brief obituary stated: