Great Linford Railway Station

That the folk of Great Linford were in need of a railway station was made crystal clear in a meeting held at Newport Pagnell on Monday November 2nd, 1863. As reported in Croydon’s Weekly Standard newspaper of the following Saturday, the well-attended gathering was convened at the Swan Hotel to provide a forum for citizens concerned at delays in building a longed for railway line between Wolverton and Newport Pagnell, and which was to pass through Great Linford. In reviewing the economic potential of the line, it was stated by a Mr W. B. Bull that upwards of 70 men routinely walked to and from Great Linford to their place of work at Wolverton Railway Works. This would have represented a journey of about an hour each way. Mr Bull further observed that these men would, “gladly pay 1 shilling per week to be conveyed by rail.”

That the folk of Great Linford were in need of a railway station was made crystal clear in a meeting held at Newport Pagnell on Monday November 2nd, 1863. As reported in Croydon’s Weekly Standard newspaper of the following Saturday, the well-attended gathering was convened at the Swan Hotel to provide a forum for citizens concerned at delays in building a longed for railway line between Wolverton and Newport Pagnell, and which was to pass through Great Linford. In reviewing the economic potential of the line, it was stated by a Mr W. B. Bull that upwards of 70 men routinely walked to and from Great Linford to their place of work at Wolverton Railway Works. This would have represented a journey of about an hour each way. Mr Bull further observed that these men would, “gladly pay 1 shilling per week to be conveyed by rail.”

Rival routes and false dawns

A railway station for Great Linford had certainly been a long time coming. Bill Simpson, in his book The Wolverton to Newport Branch reports that decades earlier in June of 1844, a meeting had been held at the very same Swan Hotel to inaugurate the “Wolverton, Newport Pagnell and Bedford Railway Company.” The presumption (though no proof has yet come to light) is that the line was intended to pass through Great Linford. The Bedfordshire Mercury of June 1st does carry news of a meeting held a little earlier in Newport Pagnell on May 24th, at which several routes for a railway line were discussed, but also reveals tensions between the advocates of two different schemes, one of which proposed connecting Bletchley to Bedford, and another from Bedford that would bypass Bletchley and instead go via Newport Pagnell and hence to Wolverton.

The chief cheerleader of the Bletchley to Bedford line was none other than the railway pioneer George Stephenson, but the rival route was endorsed at the meeting, with a man named as Shepherd tasked with surveying the route. Meanwhile the Bedford to Bletchley line went ahead, opening on November 17th, 1846. That would seem to have put paid to the plans of the Wolverton, Newport Pagnell and Bedford Railway company, however there was another interested party looking at connecting Wolverton with the Bedford line, and this we know for certain was to pass through Great Linford.

The Bucks Gazette of Saturday November 8th, 1845 carried a detailed announcement that an act of Parliament was to be sought by the London and Birmingham Railway Company (LB&R) authorising a line to begin at Wolverton, proceeding though to Bradwell, Stanton Bury (SIC), Great Linford, Newport Pagnell, Caldecot, Tickford, Moulsoe, Broughton, Wavendon, Cranfield, Salford, Hulcote, Aspley Guise, Husborne Crawley, Ridgemont and Lidlington. The plan required a new junction at Wolverton where the London to Birmingham railway passed, with another junction at Ridgemont where it would meet the Bedford to Bletchley line.

On January 6th, 1846, a formal approach was made to the clerk of the Newport Pagnell Canal Company (with its wharf at Great Linford) to purchase their waterway, which would be decommissioned and repurposed for the use of the railway. A price of £10,000 was speedily negotiated (the canal was not making the returns its backers had anticipated), but opposition mounted, notably from the Duke of Bedford, who was said to have called it, “that useless railway.”

Perhaps it was powerful vested interests that were responsible, but upon the somewhat vague sounding grounds that the purchasing powers for the Newport Pagnell Canal had not been sufficiently advertised, the act was rejected by parliament. However, on November 14h, 1846, the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) company formally announced in newspapers that they too were intent on obtaining an act of parliament that would bring a railway line through Great Linford. They would repeat the announcement across 3 consecutive weeks, a statutory legal requirement of any company wishing to build a railway. This line was to be much longer and more ambitious one than the earlier attempt, starting in Bletchley and terminating at Wellingborough. In this case an act of parliament was successfully passed in 1847, but for reasons that are not entirely clear, this venture also foundered and was left unrealised, though Bill Simpson speculates that the rival Great Northern Railway (GNR) had took the wind out of the LNWR by its realisation of a connection to Peterborough. If the impression is given that the railway companies were engaged in a bitterly contested rivalry, this would not be far short of the truth, but for now at least, Great Linford seems to have faded from minds, and it would be over 20 years more before the village finally gained a railway station.

The chief cheerleader of the Bletchley to Bedford line was none other than the railway pioneer George Stephenson, but the rival route was endorsed at the meeting, with a man named as Shepherd tasked with surveying the route. Meanwhile the Bedford to Bletchley line went ahead, opening on November 17th, 1846. That would seem to have put paid to the plans of the Wolverton, Newport Pagnell and Bedford Railway company, however there was another interested party looking at connecting Wolverton with the Bedford line, and this we know for certain was to pass through Great Linford.

The Bucks Gazette of Saturday November 8th, 1845 carried a detailed announcement that an act of Parliament was to be sought by the London and Birmingham Railway Company (LB&R) authorising a line to begin at Wolverton, proceeding though to Bradwell, Stanton Bury (SIC), Great Linford, Newport Pagnell, Caldecot, Tickford, Moulsoe, Broughton, Wavendon, Cranfield, Salford, Hulcote, Aspley Guise, Husborne Crawley, Ridgemont and Lidlington. The plan required a new junction at Wolverton where the London to Birmingham railway passed, with another junction at Ridgemont where it would meet the Bedford to Bletchley line.

On January 6th, 1846, a formal approach was made to the clerk of the Newport Pagnell Canal Company (with its wharf at Great Linford) to purchase their waterway, which would be decommissioned and repurposed for the use of the railway. A price of £10,000 was speedily negotiated (the canal was not making the returns its backers had anticipated), but opposition mounted, notably from the Duke of Bedford, who was said to have called it, “that useless railway.”

Perhaps it was powerful vested interests that were responsible, but upon the somewhat vague sounding grounds that the purchasing powers for the Newport Pagnell Canal had not been sufficiently advertised, the act was rejected by parliament. However, on November 14h, 1846, the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) company formally announced in newspapers that they too were intent on obtaining an act of parliament that would bring a railway line through Great Linford. They would repeat the announcement across 3 consecutive weeks, a statutory legal requirement of any company wishing to build a railway. This line was to be much longer and more ambitious one than the earlier attempt, starting in Bletchley and terminating at Wellingborough. In this case an act of parliament was successfully passed in 1847, but for reasons that are not entirely clear, this venture also foundered and was left unrealised, though Bill Simpson speculates that the rival Great Northern Railway (GNR) had took the wind out of the LNWR by its realisation of a connection to Peterborough. If the impression is given that the railway companies were engaged in a bitterly contested rivalry, this would not be far short of the truth, but for now at least, Great Linford seems to have faded from minds, and it would be over 20 years more before the village finally gained a railway station.

Formation of the Newport Pagnell Railway Company

The LNWR did dally briefly with a new scheme in 1859, which given it replicated some of the previously surveyed route for their proposed service to Wellingborough, would likely have passed through Great Linford. The project was however quickly abandoned, and it was not until November of 1862 that the newly formed Newport Pagnell Railway Company (NPR) set about advertising its intention to obtain an act of parliament to build a line that would pass though Great Linford. The announcement carried in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of November 15th spoke of a railway, “to pass thence through or into the following parishes and places, or some of them, that is to say, Wolverton, Bradwell, Stanton Bury, Great Linford and Newport Pagnell.” The notice also revived the idea of purchasing the Newport Pagnell Canal in order to, “stop up and divert the waters of the said canal, and to discontinue it as a canal, and to appropriate it, or so much or such parts thereof, as may be necessary for the purposes of the said intended railway.”

The act was not however unopposed. A parliamentary committee meeting held on June 16th, 1863 to consider the act was attended by a number of Newport Pagnell citizens who argued in favour of the railway, while it was also noted that, “the bill was strongly opposed by the Grand Junction Canal Company.” Clearly they stood to lose trade to a new railway, but despite their opposition the act was passed on June 29th, 1863. The act confirmed the powers necessary to purchase the canal and to raise the £45,000 cost of construction that had been estimated, but by the time of the aforementioned meeting at the Swan Inn of November 2nd, 1863, a deficit in the required funds had emerged.

It was decided at the meeting that a deputation would be sent to deliver a “memorial” to the London and North Western Railway for, “pecuniary assistance.” In effect then, a begging letter. In brief, the memorial appealed to the board of the LNWR that the Newport Pagnell Railway line would be a good investment, and that any capital they saw fit to provide would surely reap a handsome reward. It is not yet entirely clear if the LNWR stumped up the funds, but by May of the following year the plans to purchase the Newport Pagnell Canal were well advanced at a cost of £9,000, with a notice issued to announce the closure. Subsequently, Croydon’s Weekly Standard newspaper announced the death knell for the canal in its issue of Saturday May 28th, 1864, with the news that the Newport Pagnell Railway company was to stop up the waterway from August 28th that year.

The act was not however unopposed. A parliamentary committee meeting held on June 16th, 1863 to consider the act was attended by a number of Newport Pagnell citizens who argued in favour of the railway, while it was also noted that, “the bill was strongly opposed by the Grand Junction Canal Company.” Clearly they stood to lose trade to a new railway, but despite their opposition the act was passed on June 29th, 1863. The act confirmed the powers necessary to purchase the canal and to raise the £45,000 cost of construction that had been estimated, but by the time of the aforementioned meeting at the Swan Inn of November 2nd, 1863, a deficit in the required funds had emerged.

It was decided at the meeting that a deputation would be sent to deliver a “memorial” to the London and North Western Railway for, “pecuniary assistance.” In effect then, a begging letter. In brief, the memorial appealed to the board of the LNWR that the Newport Pagnell Railway line would be a good investment, and that any capital they saw fit to provide would surely reap a handsome reward. It is not yet entirely clear if the LNWR stumped up the funds, but by May of the following year the plans to purchase the Newport Pagnell Canal were well advanced at a cost of £9,000, with a notice issued to announce the closure. Subsequently, Croydon’s Weekly Standard newspaper announced the death knell for the canal in its issue of Saturday May 28th, 1864, with the news that the Newport Pagnell Railway company was to stop up the waterway from August 28th that year.

Objection from the Reverend Uthwatt

Just as the canal had previously cut a swathe through Great Linford Manor Park and angered the then lord of the manor for the loss and damage done, so to the compulsory purchase of land for the railway was to prove a vexing issue for the present incumbent, the Reverend William Uthwatt. Like his predecessor Henry Uthwatt, the Reverend was not about to take this insult lying down. On November 21st, 1864, a Sheriff’s Court jury of “12 highly respected men of the county” was convened at the County Arms Inn in Bradwell, and a pleasant sounding day’s diversion it sounds, beginning with a carriage ride to see the land in question, before returning to the Inn for lunch, after which the jury got down to work.

Several newspapers ran substantial accounts of the proceedings, including the Bucks Herald of November 26th, from which we learn that a Q.C named Huddleston represented the Reverend Uthwatt. This was perhaps John Walter Huddleston, who had established an eminent reputation in various causes célèbres. Huddleston’s case hinged on a number of points including the timber value of the trees cut down and that the railway bisected and thereby diminished the value of several fields. The jury were also asked to consider the question of “residential injury”, specifically that the railway embankment, “crossed through the very best part of Mr. Uthwatt’s property” and would be visible from the manor grounds and the summer house, which could surely be a reference to the Doric Seat?

Most contentiously however was the question of the value of the stone under the land. Great Linford has plentiful deposits of limestone; there is a disused quarry by the canal (then owned by the Uthwatt family), from which it is likely many houses in the village and vicinity have obtained building materials. Arguably, the Reverend Uthwatt’s Q.C seemed to have a rock solid case, as he had demonstrated during the jury’s visit to the land that the company had reduced their purchase of bricks and were instead obtaining stone freely to hand from their railway cutting. Such was the high character of this stone that they were even using it in the construction of the railway bridge over the canal, and had approached the Reverend Uthwatt with a request to purchase more, a request he had refused. But the railway company’s own legal counsel, a Mr Hawkins, was having none of it, arguing that no actual existing quarry had been intruded upon by the railway company and that the demands of the Reverend Uthwatt were, “most monstrous”. Expert witnesses were called to attest to the value of the land, with much evidence presented as regards sample cores taken to ascertain the depth of the stone deposits. The Reverend himself was cross-examined, stating that he had no desire to part with any part of his property, that there were windows in his house which commanded a view of the railway, and repeated the claim that he could see it from his summer house.

Huddleston proposed a figure in the region of £5000 in total for the land, stone and distress, but Hawkins countered that £1,040 would be a more reasonable figure. The jury then retired and taking just a few minutes to deliberate returned a verdict of £1,790 for the Reverend Uthwatt, significantly less than he had hoped for.

As an interesting digression, there has been at least one other person in Great Linford who saw fit to object to the notion of railways intruding on their land, though not in this case the Newport Pagnell railway. The Stamford Mercury newspaper of November 11th, 1836 carried a declaration from a list of objectors to the proposed compulsory purchase of land to accommodate the building of the South Midlands Counties Railway, among them William Smyth, described as a clerk of Great Linford. Smyth was actually the rector of Great Linford, and clearly had land elsewhere in the country that was falling foul of a compulsory purchase order from the railway, which was intended to connect Nottingham, Leicester and Derby with Rugby.

Several newspapers ran substantial accounts of the proceedings, including the Bucks Herald of November 26th, from which we learn that a Q.C named Huddleston represented the Reverend Uthwatt. This was perhaps John Walter Huddleston, who had established an eminent reputation in various causes célèbres. Huddleston’s case hinged on a number of points including the timber value of the trees cut down and that the railway bisected and thereby diminished the value of several fields. The jury were also asked to consider the question of “residential injury”, specifically that the railway embankment, “crossed through the very best part of Mr. Uthwatt’s property” and would be visible from the manor grounds and the summer house, which could surely be a reference to the Doric Seat?

Most contentiously however was the question of the value of the stone under the land. Great Linford has plentiful deposits of limestone; there is a disused quarry by the canal (then owned by the Uthwatt family), from which it is likely many houses in the village and vicinity have obtained building materials. Arguably, the Reverend Uthwatt’s Q.C seemed to have a rock solid case, as he had demonstrated during the jury’s visit to the land that the company had reduced their purchase of bricks and were instead obtaining stone freely to hand from their railway cutting. Such was the high character of this stone that they were even using it in the construction of the railway bridge over the canal, and had approached the Reverend Uthwatt with a request to purchase more, a request he had refused. But the railway company’s own legal counsel, a Mr Hawkins, was having none of it, arguing that no actual existing quarry had been intruded upon by the railway company and that the demands of the Reverend Uthwatt were, “most monstrous”. Expert witnesses were called to attest to the value of the land, with much evidence presented as regards sample cores taken to ascertain the depth of the stone deposits. The Reverend himself was cross-examined, stating that he had no desire to part with any part of his property, that there were windows in his house which commanded a view of the railway, and repeated the claim that he could see it from his summer house.

Huddleston proposed a figure in the region of £5000 in total for the land, stone and distress, but Hawkins countered that £1,040 would be a more reasonable figure. The jury then retired and taking just a few minutes to deliberate returned a verdict of £1,790 for the Reverend Uthwatt, significantly less than he had hoped for.

As an interesting digression, there has been at least one other person in Great Linford who saw fit to object to the notion of railways intruding on their land, though not in this case the Newport Pagnell railway. The Stamford Mercury newspaper of November 11th, 1836 carried a declaration from a list of objectors to the proposed compulsory purchase of land to accommodate the building of the South Midlands Counties Railway, among them William Smyth, described as a clerk of Great Linford. Smyth was actually the rector of Great Linford, and clearly had land elsewhere in the country that was falling foul of a compulsory purchase order from the railway, which was intended to connect Nottingham, Leicester and Derby with Rugby.

On track at last

A detailed account provided by the Bicester Herald of April 28th, 1865 provides fascinating details of the work undertaken around Great Linford, including an account of the challenges posed in the construction of the impressive bridge over the Grand Junction Canal, which still stands to this day.

The bridge over the Grand Junction has been the most difficult piece of the work on the line; it is composed partly of masonry and partly of iron and timber, the abutments are built of solid masonry, the foundations being on rock – for building these foundations below the level of the water in the canal, dams were made of planks on edge, with clay puddle a foot thick well rammed in between them, the two sides being secured by iron bars and stays driven into the bottom of the canal. These means succeeded so well that pumps were not required to be used after the water was once got out, and upon the completion of the masonry the dams were easily removed. The masonry above the foundations was built in the usual manner, and at the proper level large blocks of stone, four feet square and weighing about a ton each were inserted, on which the castings were bedded to receive the ends of the girders. The girders, which are on the lattice principle, were made of wrought iron, at the works of Kennard Brothers in Wales, and were sent in segments. The main girders, which give a clear span of 82 feet, were fitted and riveted together on the embarkment close to the canal, and were then rolled forward into their position on the abutments. Two canal boats were fastened together and timber framing erected upon them to carry the end of end of each girder across the span; cross girders are placed upon the bottom beams of the main girders about 5 feet apart, and upon these planking is bolted down, which will carry the ballast and rails. Over the small opening for the bridle way to Great Linford two small plate girders have been erected, and the whole presents a very strong and handsome appearance. The headway over the canal is ten feet, and the total weight of iron used in the construction of the bridge is about 48 tons.

The same article also provides the remarkable statistic that another 30,000 loads of earth were then still needed to complete the more than quarter mile embankment running from the bridge in the direction of Newport Pagnell. Also noted is that the bridge for the parish road to Great Linford was complete (on modern day Marsh Drive) as was the platform for Great Linford station, with the station building itself still under construction.

Oddly, despite the fact that more than one railway company had expressed a desire to purchase the Newport Pagnell Canal with the avowed intention to use the same route, this apparently did not come to pass; the Newport Pagnell Railway company while following alongside the general route of the canal, did not as might be expected actually fill in the canal and run track along it’s precise route. The work to achieve this would seem in hindsight seem to be extremely labour intensive, so perhaps the intention was always first and foremost to remove a competitor. However, equally oddly, and contradicting the prevailing wisdom on the route followed, the Bicester Herald article makes the following observation. “The railway from Linford passes through Linford cutting, which is completed, and thence emerges into what was once the Newport Pagnell Canal, the work along which has been rather wet, but the late dry weather has consolidated it very much, and the formation is now very hard and dry.”

The same article also provides the remarkable statistic that another 30,000 loads of earth were then still needed to complete the more than quarter mile embankment running from the bridge in the direction of Newport Pagnell. Also noted is that the bridge for the parish road to Great Linford was complete (on modern day Marsh Drive) as was the platform for Great Linford station, with the station building itself still under construction.

Oddly, despite the fact that more than one railway company had expressed a desire to purchase the Newport Pagnell Canal with the avowed intention to use the same route, this apparently did not come to pass; the Newport Pagnell Railway company while following alongside the general route of the canal, did not as might be expected actually fill in the canal and run track along it’s precise route. The work to achieve this would seem in hindsight seem to be extremely labour intensive, so perhaps the intention was always first and foremost to remove a competitor. However, equally oddly, and contradicting the prevailing wisdom on the route followed, the Bicester Herald article makes the following observation. “The railway from Linford passes through Linford cutting, which is completed, and thence emerges into what was once the Newport Pagnell Canal, the work along which has been rather wet, but the late dry weather has consolidated it very much, and the formation is now very hard and dry.”

Not yet up to full steam

The Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette of August 8th, 1865 reported on the half yearly shareholders meeting that had been held in the Westminster offices of the company, with an abundance of optimism expressed by the directors, who were able to state, “that the progress of the works had been so satisfactory since their commencement in the summer of 1864 that the line was expected to be ready for opening in the course of the ensuing Autumn.” It was further reported that, “with the exception of No. 1 cutting at the junction at Wolverton, and No. 5 embankment at Great Linford, the earthwork had been completed. About 15,000 cubic yards yet remained to be filled into this embarkment, which was been proceeded with as rapidly as possible, as the contractors had now a locomotive constantly at work on the line.” It was also stated that the company had successfully promoted a second parliamentary bill for an extension of the line to Olney. The company duly authorised a new issue of shares with the aim of raising a further £80,000 of financing.

On Saturday September 30th, 1865, the first train made the journey from Wolverton to Newport Pagnell with 17 ballast wagons filled with navvies, who doubtless proceeded to paint the town red, but while the line was clearly in working order, there was still much to be done. Unfortunately it appears that things then took a less rosy turn, with delays and setbacks frequently tasking the patience of the town and village folk the NPR was pledged to serve. A shareholders meeting held in early August of 1866 and reported in the Northampton Mercury of August 11th was certainly a less sanguine affair than the one a year previously, with several critical issues to be reported, notably that “prevalent commercial pressure” had caused a temporary suspension of work by the contractor (a company called Bray and Wilson), by which one would presume to mean they had not been paid. This had also caused the suspension of work on the Olney extension. Additionally, concerns had been voiced by a government inspector on the arrangements made with the LNWR at Wolverton for the required new junction, which had delayed the necessary approval of the board of trade for the commencement of public passenger services. However, the line had been opened for the carriage of coals and other goods at favourable rates, but perhaps suggestive of the company’s ambitions outstripping its abilities, it was further reported that a third act of parliament was in the process of receiving the royal assent, this time extending the line to Wellingborough. To date, the company had burnt through £122,086, far more than the £45,000 originally proposed.

By the 1866 shareholders meeting of March 27th, 1866, the opening of the line had still not occurred, with unspecified delays coming to an agreement with the LNWR at Wolverton offered as an explanation, though the directors continued to be optimistic, with the Olney portion of the line reported to be well under way.

The delays were not however going unremarked upon. The Newport Pagnell Gazetter of August 3rd, 1867 had harsh words for the directors of the company, criticising the delays and several failed promises of an opening date for passengers, which had only served to raise false hopes. In what might be seen as evidence of further troubles, Croydon’s Weekly Standard of August 17th carried accounts of several court cases that had been instigated to recover unpaid bills from the company.

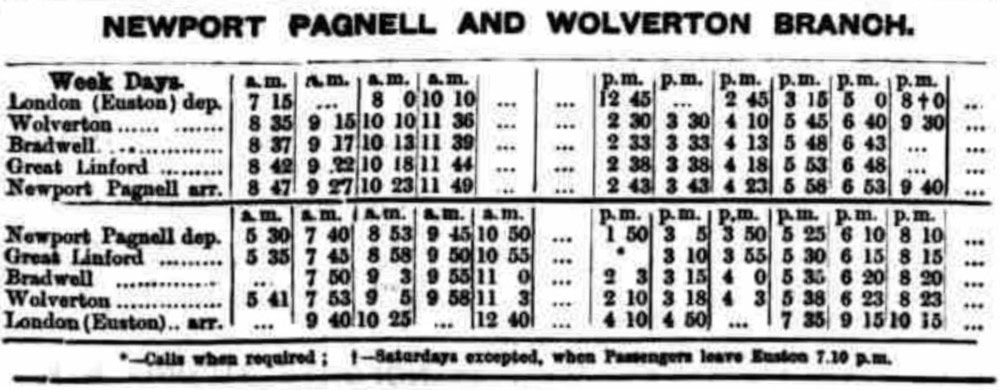

In what could be seen as a salve to the bruised feelings of the community, the company had in July begun providing free travel to livestock dealers, but finally on Monday September 2nd, 1867, the line was opened to passengers, prompting church bells to be rung in Newport Pagnell and much rejoicing. Initially there were 8 trains per day running, with the earliest weekday train departing Great Linford for Wolverton at 5.45am, and the last evening train arriving at 8.08pm. It is interesting to note that the “weekday” trains ran Monday to Saturday, with Sunday being the only recognised day off, with a much reduced service.

On Saturday September 30th, 1865, the first train made the journey from Wolverton to Newport Pagnell with 17 ballast wagons filled with navvies, who doubtless proceeded to paint the town red, but while the line was clearly in working order, there was still much to be done. Unfortunately it appears that things then took a less rosy turn, with delays and setbacks frequently tasking the patience of the town and village folk the NPR was pledged to serve. A shareholders meeting held in early August of 1866 and reported in the Northampton Mercury of August 11th was certainly a less sanguine affair than the one a year previously, with several critical issues to be reported, notably that “prevalent commercial pressure” had caused a temporary suspension of work by the contractor (a company called Bray and Wilson), by which one would presume to mean they had not been paid. This had also caused the suspension of work on the Olney extension. Additionally, concerns had been voiced by a government inspector on the arrangements made with the LNWR at Wolverton for the required new junction, which had delayed the necessary approval of the board of trade for the commencement of public passenger services. However, the line had been opened for the carriage of coals and other goods at favourable rates, but perhaps suggestive of the company’s ambitions outstripping its abilities, it was further reported that a third act of parliament was in the process of receiving the royal assent, this time extending the line to Wellingborough. To date, the company had burnt through £122,086, far more than the £45,000 originally proposed.

By the 1866 shareholders meeting of March 27th, 1866, the opening of the line had still not occurred, with unspecified delays coming to an agreement with the LNWR at Wolverton offered as an explanation, though the directors continued to be optimistic, with the Olney portion of the line reported to be well under way.

The delays were not however going unremarked upon. The Newport Pagnell Gazetter of August 3rd, 1867 had harsh words for the directors of the company, criticising the delays and several failed promises of an opening date for passengers, which had only served to raise false hopes. In what might be seen as evidence of further troubles, Croydon’s Weekly Standard of August 17th carried accounts of several court cases that had been instigated to recover unpaid bills from the company.

In what could be seen as a salve to the bruised feelings of the community, the company had in July begun providing free travel to livestock dealers, but finally on Monday September 2nd, 1867, the line was opened to passengers, prompting church bells to be rung in Newport Pagnell and much rejoicing. Initially there were 8 trains per day running, with the earliest weekday train departing Great Linford for Wolverton at 5.45am, and the last evening train arriving at 8.08pm. It is interesting to note that the “weekday” trains ran Monday to Saturday, with Sunday being the only recognised day off, with a much reduced service.

Surrender to the LNWR

The problems for the Newport Pagnell Railway Company were not however over. The relationship with the LNWR was never cordial, with disputes festering over payments due the LNWR for the use of their facilities and services at Wolverton junction. This quickly came to the boil in the early 1870s, which also coincided with the growing realisation that the NPR had overstretched itself and the future of the Olney extension was in serious peril. The LNWR had found the Olney extension a bitter pill to swallow, as its completion would take business away from them and give the Newport Pagnell Railway Company a much stronger hand in negotiations. This perhaps does much to explain the bad feeling between the two companies, and the high charges levied by the LNWR, which in amounting to £500 per year, caused one director of the NPR to remark that this was, “like a shopkeeper charging his customers to come into his shop.”

It was an unequal battle, and on July 3rd 1873 the NPR inevitably found itself forced to offer itself for sale to the LNWR. The LNWR was quick to accept, on the proviso that the detested Olney line was immediately abandoned. On June 29th. In 1875 the little line was swallowed by the LNWR.

Of interest, the LNWR made a pre-sale inventory of the facilities it was to purchase, and found the following at Great Linford railway station, here reproduced from Bill Simpson’s book. It seems that the NPR had not spent much money on upkeep.

Waiting room – 3 Chairs

Booking office – 6 Chairs, looking glass, firegrate, fender, fire irons (broken) clock (two faces), dating press, ticket box (75 tubes), ruler, counter with drawers.

Coal cellar – small notice board , 3 signal lamps for distant and home signals.

Platform – 2 Lamps, 1 Lime bill board, 1 byelaws in frame, 2 levers for distant signalling (not in use), 1 home signal, 2 cisterns for platform oil lamps, pump (no water) 2 hand lamps, 1 oil can, 1 oil feeder, 1 name board.

It was also noted that there was a WC, but that the walls were very damp due to leaky tanks, and the waiting room was in a very bad condition from water leakage, and that the names boards were in need of repainting.

It was an unequal battle, and on July 3rd 1873 the NPR inevitably found itself forced to offer itself for sale to the LNWR. The LNWR was quick to accept, on the proviso that the detested Olney line was immediately abandoned. On June 29th. In 1875 the little line was swallowed by the LNWR.

Of interest, the LNWR made a pre-sale inventory of the facilities it was to purchase, and found the following at Great Linford railway station, here reproduced from Bill Simpson’s book. It seems that the NPR had not spent much money on upkeep.

Waiting room – 3 Chairs

Booking office – 6 Chairs, looking glass, firegrate, fender, fire irons (broken) clock (two faces), dating press, ticket box (75 tubes), ruler, counter with drawers.

Coal cellar – small notice board , 3 signal lamps for distant and home signals.

Platform – 2 Lamps, 1 Lime bill board, 1 byelaws in frame, 2 levers for distant signalling (not in use), 1 home signal, 2 cisterns for platform oil lamps, pump (no water) 2 hand lamps, 1 oil can, 1 oil feeder, 1 name board.

It was also noted that there was a WC, but that the walls were very damp due to leaky tanks, and the waiting room was in a very bad condition from water leakage, and that the names boards were in need of repainting.

A century of service

The LNWR had made a potentially good investment. At the time of their acquisition the service was carrying some 600 men and boys each day to and from the Wolverton Railway Works, with 92 men and 8 boys recorded circa 1875 as travelling from Linford at a weekly cost of 1 shilling each. Normally there were two coaches in use, but for the morning rush hour to Wolverton there were six, though the conditions in the cramped compartments were poor, and it was said that the lighting was so dim that to read a newspaper a man had to light a candle. There was also money to be made from casual passengers and freight; for instance we know from a notice carried in the Buckingham Express of August 10th, 1895 that a farm was offered up for rent by the Uthwatts and that a selling point was that milk was sent from Great Linford station to London twice a day. An extra coach was provided on a Wednesday to bring people to and from Newport Pagnell market, and the same was done on Fridays for the market at Wolverton. At its peak period between 1900 and 1914, there were 15 trains up and 14 trains down, though writing in the May-June 1991 issue of Back Track magazine, Bill Simpson indicates that at an undisclosed period in the history of the line, the Wolverton workers were carried for free.

Bill Simpson also makes reference in his book to the building of station master’s house in 1878, but the location of this is presently unclear. The 1901 census records a James King, station master, at the address, but it seems the LNWR was no longer using it in 1911, as the census record for this year tells us that a William Charles, a groom by profession, was now occupying the property. The station master at the time, Frederick Thomas Hawkins, was then living at number 2, Station Terrace. Two rows of these houses, surely built primarily for the burgeoning number of workers commuting to Wolverton were constructed adjacent the station (on present day Marsh drive) sometime between 1901 and 1911, the latter when the address first appears on census records.

The service appears to have been a reliable and safe one, with little in the way of anecdotes to indicate it was much delayed or in trouble, though in November of 1954, it was involved in a shunting accident at New Bradwell, which resulted in it jumping the tracks. Industrial action could of course cause delays, such as the shutting of the line in the summer of 1955 during a national rail strike.

Bill Simpson also makes reference in his book to the building of station master’s house in 1878, but the location of this is presently unclear. The 1901 census records a James King, station master, at the address, but it seems the LNWR was no longer using it in 1911, as the census record for this year tells us that a William Charles, a groom by profession, was now occupying the property. The station master at the time, Frederick Thomas Hawkins, was then living at number 2, Station Terrace. Two rows of these houses, surely built primarily for the burgeoning number of workers commuting to Wolverton were constructed adjacent the station (on present day Marsh drive) sometime between 1901 and 1911, the latter when the address first appears on census records.

The service appears to have been a reliable and safe one, with little in the way of anecdotes to indicate it was much delayed or in trouble, though in November of 1954, it was involved in a shunting accident at New Bradwell, which resulted in it jumping the tracks. Industrial action could of course cause delays, such as the shutting of the line in the summer of 1955 during a national rail strike.

Nobby or Buster?

At some point in the history of the line the affectionate nickname Newport Nobby was adopted for the engines that plied back and forth between Wolverton and Newport Pagnell, with an early reference appearing in 1954, when it was reported that the Newport Nobby had briefly derailed. It is likely that more than one train bore the name; the Buckingham Advertiser of June 25th, 1955 makes reference to “the old Newport Nobby” having moved to Bletchley. The odd name appears to have arisen from the conical protrusion on the tank engines that served the line.

The nickname Buster also seems to have been used, though it is unclear why, or precisely when this particular sobriquet was in use. Jack Ivester Lloyd, writing in the Bucks Standard of December 24th, 1965, makes no mention of the name "Newport Nobby", even going so far as to entitle his article "The Buster", which is odd as his story was prompted by the closing of the line, and every other article at the time refers consistently to the train as "Nobby." Perhaps Jack was harking back to his schooldays in the early 1900s, when he rode the train to school. Jack's account of riding "the buster" can be read here.

The nickname Buster also seems to have been used, though it is unclear why, or precisely when this particular sobriquet was in use. Jack Ivester Lloyd, writing in the Bucks Standard of December 24th, 1965, makes no mention of the name "Newport Nobby", even going so far as to entitle his article "The Buster", which is odd as his story was prompted by the closing of the line, and every other article at the time refers consistently to the train as "Nobby." Perhaps Jack was harking back to his schooldays in the early 1900s, when he rode the train to school. Jack's account of riding "the buster" can be read here.

A line in peril

In March of 1917, rumours began to swirl that Great Linford station was to be closed, but given that Wolverton Works would have been considered vital to the war effort, it seems that at most, the plans were to limit services to mornings and evenings. However, these stories were published only months before the end of the war, so it may be that they were never enacted.

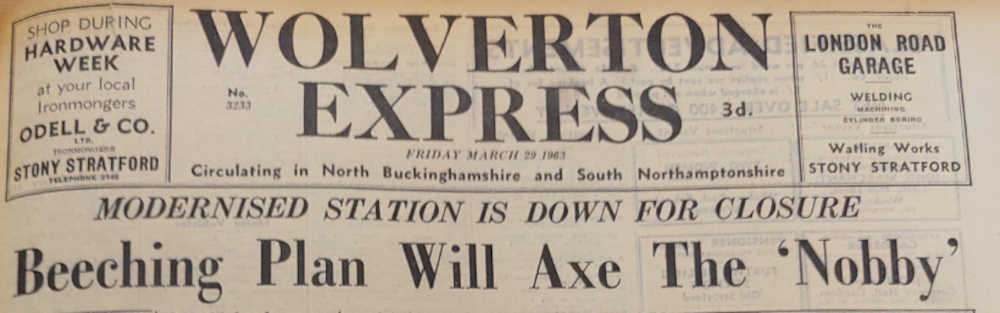

There seem to have been several more closure scares in 1953 when stories began to circulate that evening services were to be cut, or perhaps even that Great Linford station would be entirely closed. The Northampton Mercury of November 13th carried news that railway officials were considering their options on the grounds that the line had not made any money in years, and owed its survival only to the large number of railway staff who travelled on it. The threatened withdrawal of services did not then materialise, thanks it seems to public protest, though it would prove to be an omen of things to come. In march of 1963 a report was issued called The Reshaping of British Railways, but which became so synonymous with its author Richard Beeching that it is more commonly and derisively known as The Beeching Report. Not unexpectedly the closure plans made local headlines.

There seem to have been several more closure scares in 1953 when stories began to circulate that evening services were to be cut, or perhaps even that Great Linford station would be entirely closed. The Northampton Mercury of November 13th carried news that railway officials were considering their options on the grounds that the line had not made any money in years, and owed its survival only to the large number of railway staff who travelled on it. The threatened withdrawal of services did not then materialise, thanks it seems to public protest, though it would prove to be an omen of things to come. In march of 1963 a report was issued called The Reshaping of British Railways, but which became so synonymous with its author Richard Beeching that it is more commonly and derisively known as The Beeching Report. Not unexpectedly the closure plans made local headlines.

The report called for the closure of 2,363 stations and 5000 miles of track, including the Newport Pagnell line. After almost 100 years of service, the last Newport Nobby train chugged out of Great Linford station on September 5th, 1964. In a clear sign of the huge affection held for the service, Newport Nobby received a fine send off, with crowds of well-wishers (perhaps also better called mourners) waving off the train along its 4 mile route.

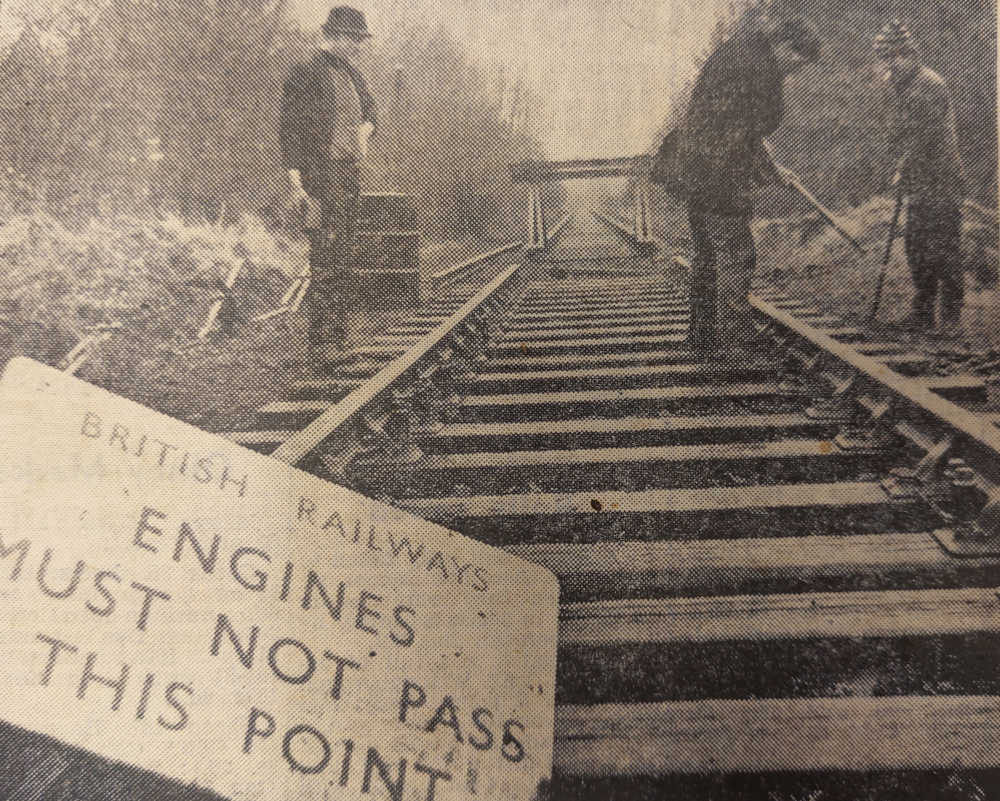

At Newport Pagnell, there was a symbolic soaking of a Mr Beeching from a cold bucket of water and the train received an enthusiastic last clean from mop wielding well-wishers. The line continued on briefly for freight only, but on February 9th, 1968 the Wolverton Express newspaper pictured the ripping up of the tracks beneath the grim headline, “Death of a railway.”

At Newport Pagnell, there was a symbolic soaking of a Mr Beeching from a cold bucket of water and the train received an enthusiastic last clean from mop wielding well-wishers. The line continued on briefly for freight only, but on February 9th, 1968 the Wolverton Express newspaper pictured the ripping up of the tracks beneath the grim headline, “Death of a railway.”

The railway at Great Linford is however not entirely lost. The route has now been converted into one of the Redways that criss-cross Milton Keynes, and though the station ticket office has long gone, the platform remains and can be easily reached from the bridge on Marsh Drive.