The Brick Making Kilns at Great Linford

Before canals and railways began to criss-cross the country, making it easy and cost effective to transport heavy mass-produced items like house bricks to their customers, villages needed to find a way to obtain these necessities. The solution very often was to make their own locally, and considering that there are brick-built houses on the High Street that can be dated to at least the 1770s, it seems reasonable to conclude that the industry was well established in the parish by then. Indeed, Buckinghamshire was well suited to brick making, blessed as it was with an abundance of suitable clay, such that in the 19th century, there was hundreds of small independent brick kilns in operation throughout the county.

Before canals and railways began to criss-cross the country, making it easy and cost effective to transport heavy mass-produced items like house bricks to their customers, villages needed to find a way to obtain these necessities. The solution very often was to make their own locally, and considering that there are brick-built houses on the High Street that can be dated to at least the 1770s, it seems reasonable to conclude that the industry was well established in the parish by then. Indeed, Buckinghamshire was well suited to brick making, blessed as it was with an abundance of suitable clay, such that in the 19th century, there was hundreds of small independent brick kilns in operation throughout the county.

The earliest known brick kilns

The earliest written reference so far found for brick making at Great Linford can be found in Pigot's Trade Directory of 1830, which includes an entry for a brick making and lime burning business under the ownership of a Keeps (spelt consistently in other documents as Keep), Labrum and Taylor. The business address is listed as The Wharf at Great Linford, with the same trio also listed as wharfingers (an archaic word for a person who runs a Wharf) and in fact it appears that they also had an interest in Shipley Wharf at Newport Pagnell, so their enterprise was quite extensive. The question arises, did they own the wharf, or were they tenants, perhaps of the Newport Pagnell Canal Company? A record dating to 1811 held at Buckinghamshire Archives (D-U/1/26) is an Appointment upon trust for sale, and listed amongst many other properties and land in Great Linford is "Great Linford wharf and warehouses, formerly in the tenure of Henry Uthwatt Uthwatt and now of William Wilson and Ralph Wilson as his tenants." Also mentioned is the Wharf Inn, also in the occupation of William Wilson and Ralph Wilson. It seems then that for a time at least, the Uthwatts of Great Linford Manor held a financial interest in the Wharf, and perhaps also brick making in the village.

Further research is required on William and Ralph Wilson (perhaps brothers), but we know something about Keep, Labrum and Taylor. The partnership was dissolved in 1840, from which announcement we can infer that George Labrum was one of the trio, a corn dealer residing in Newport Pagnell, while John Keep, an ironmonger also of Newport Pagnell appears to have been another, though at the time of the dissolution of the partnership, there was no longer a Taylor participating in the business, his place having been succeeded by another Keep, a William, who presumably must have been a relative of John; the obvious inference is that they were father and son.

Intriguingly, a William Taylor was buried at Great Linford on August 2nd, 1833 and while no evidence has yet emerged to confirm he was one of the original partners in the brickyard and wharf, he does seem a plausible candidate. Presuming then that he was one of the original partners, a few years after his death it seems that a decision was taken to split the brickyard away from the business, with a prominent advert in The Northampton Mercury newspaper of August 1st, 1835 making the call, “To Brickmakers and others”, that a large dwelling house was to be auctioned later that month, with an adjoining brick-yard in full trade and land suitable for digging clay. The advert details some of the facilities on hand, including brick and lime kilns, sheds and “every other convenience for carrying on an extensive business.”

In common with property sales of this period, the advert also helpfully names the occupiers, a Mrs Taylor and a Mr Thomas Kemp; the former of particular interest as we already know the name Taylor was associated with the brickyard in 1830. While it is unlikely given the societal restrictions of the times that she was one of the original partners, the appearance of a Mrs Taylor in this story makes her a good fit to be the widow of William Taylor, and rather intriguingly it does seem that she would subsequently acquire a controlling interest in the brickyard. We know this because we can refer to the 1840 Tithe Map for Great Linford, which not only allows us to confirm the location of the brick yard and kilns as adjacent to the Wharf, but also tells us that a Mary Ann Taylor is both owner and occupier of a, “House, Garden, Brickyard and Close.” It seems entirely likely that the Mrs Taylor in the sale notice and the Mary Ann on the Tithe Map are one and the same person. All trace of this early brickyard in Great Linford have long since vanished under new developments, though elements of the Wharf still survive, as does the Wharf Inn (now a private house) where the 1835 auction had been scheduled to take place.

Further research is required on William and Ralph Wilson (perhaps brothers), but we know something about Keep, Labrum and Taylor. The partnership was dissolved in 1840, from which announcement we can infer that George Labrum was one of the trio, a corn dealer residing in Newport Pagnell, while John Keep, an ironmonger also of Newport Pagnell appears to have been another, though at the time of the dissolution of the partnership, there was no longer a Taylor participating in the business, his place having been succeeded by another Keep, a William, who presumably must have been a relative of John; the obvious inference is that they were father and son.

Intriguingly, a William Taylor was buried at Great Linford on August 2nd, 1833 and while no evidence has yet emerged to confirm he was one of the original partners in the brickyard and wharf, he does seem a plausible candidate. Presuming then that he was one of the original partners, a few years after his death it seems that a decision was taken to split the brickyard away from the business, with a prominent advert in The Northampton Mercury newspaper of August 1st, 1835 making the call, “To Brickmakers and others”, that a large dwelling house was to be auctioned later that month, with an adjoining brick-yard in full trade and land suitable for digging clay. The advert details some of the facilities on hand, including brick and lime kilns, sheds and “every other convenience for carrying on an extensive business.”

In common with property sales of this period, the advert also helpfully names the occupiers, a Mrs Taylor and a Mr Thomas Kemp; the former of particular interest as we already know the name Taylor was associated with the brickyard in 1830. While it is unlikely given the societal restrictions of the times that she was one of the original partners, the appearance of a Mrs Taylor in this story makes her a good fit to be the widow of William Taylor, and rather intriguingly it does seem that she would subsequently acquire a controlling interest in the brickyard. We know this because we can refer to the 1840 Tithe Map for Great Linford, which not only allows us to confirm the location of the brick yard and kilns as adjacent to the Wharf, but also tells us that a Mary Ann Taylor is both owner and occupier of a, “House, Garden, Brickyard and Close.” It seems entirely likely that the Mrs Taylor in the sale notice and the Mary Ann on the Tithe Map are one and the same person. All trace of this early brickyard in Great Linford have long since vanished under new developments, though elements of the Wharf still survive, as does the Wharf Inn (now a private house) where the 1835 auction had been scheduled to take place.

A Thomas Kemp Junior, whom we must presume to be the other person named in the sale advertisement can also be found on the Tithe Map, located on the opposite side of the road to the brickyard in a house owned by Henry Andrewes Uthwatt. This may be the house standing today on the site called Canal Cottage. Thomas is identified on the 1841 census as a 35-year-old dealer in hay.

But If Mary is the owner and occupier in 1840 then what of the sale of 1835? It seems to have been common practice to announce in the newspapers when a business changed hands, but no such notice is evident in this case. Was the sale cancelled; had it perhaps failed to reach the reserve price, or could there be another explanation? Mary was clearly occupying the property in 1835, but she wasn’t the owner. If her husband had died in 1833 then did his business partners allow her to stay as a gesture to their late partner or did she gain some rights and financial resources by inheritance; could it be that she was in a position in 1835 to purchase the brickyard? Certainly, in some manner, either by purchase or inheritance, she did assume ownership.

However, by 1841 it does seem she had sold up, quite likely to a Richard Sheppard, who is listed in the 1842 edition of Pigot's Trade Directory for Great Linford under the heading of Brick Makers and Lime Burners. As for Mary, a person of that name appears on the 1841 census for Great Linford, but now living in the same household as a young clergyman named William Law. Her name comes first on the household schedule, which suggests she was the titular head of the house. Law was briefly the priest of Great Linford from 1838 to 1842, so it seems that Mary had now departed the brick-yard and was perhaps renting a room to Willian Law, very possibly at Canal Cottage.

In an interesting aside, William Law should have been living in the Rectory, but we know that in this period, the Rector of the parish, Francis Litchfield, flying in the face of convention, was renting out the Rectory rather than allowing his elected parish priest stay there.

Lacking though it is in detail, we can find a few additional titbits of information about Mary from the 1841 census. Her age is given as 44, which places her year of birth as 1797 and she is living on independent means and was born outside the county of Buckinghamshire. Alas Mary seems to disappear after 1841, with no further records to be found such as a burial at Great Linford. If by some chance she was related to the reverend William Law or had some other tie to him, then perhaps she went with him when he departed Great Linford in 1842 to take up a new post at Marston Trussell in Northamptonshire, but again there appears to be no record to support this. This is a shame, as it seems she was an interesting woman for her time, possibly taking on a substantial business in a male dominated world. It would be nice to know more about her.

But If Mary is the owner and occupier in 1840 then what of the sale of 1835? It seems to have been common practice to announce in the newspapers when a business changed hands, but no such notice is evident in this case. Was the sale cancelled; had it perhaps failed to reach the reserve price, or could there be another explanation? Mary was clearly occupying the property in 1835, but she wasn’t the owner. If her husband had died in 1833 then did his business partners allow her to stay as a gesture to their late partner or did she gain some rights and financial resources by inheritance; could it be that she was in a position in 1835 to purchase the brickyard? Certainly, in some manner, either by purchase or inheritance, she did assume ownership.

However, by 1841 it does seem she had sold up, quite likely to a Richard Sheppard, who is listed in the 1842 edition of Pigot's Trade Directory for Great Linford under the heading of Brick Makers and Lime Burners. As for Mary, a person of that name appears on the 1841 census for Great Linford, but now living in the same household as a young clergyman named William Law. Her name comes first on the household schedule, which suggests she was the titular head of the house. Law was briefly the priest of Great Linford from 1838 to 1842, so it seems that Mary had now departed the brick-yard and was perhaps renting a room to Willian Law, very possibly at Canal Cottage.

In an interesting aside, William Law should have been living in the Rectory, but we know that in this period, the Rector of the parish, Francis Litchfield, flying in the face of convention, was renting out the Rectory rather than allowing his elected parish priest stay there.

Lacking though it is in detail, we can find a few additional titbits of information about Mary from the 1841 census. Her age is given as 44, which places her year of birth as 1797 and she is living on independent means and was born outside the county of Buckinghamshire. Alas Mary seems to disappear after 1841, with no further records to be found such as a burial at Great Linford. If by some chance she was related to the reverend William Law or had some other tie to him, then perhaps she went with him when he departed Great Linford in 1842 to take up a new post at Marston Trussell in Northamptonshire, but again there appears to be no record to support this. This is a shame, as it seems she was an interesting woman for her time, possibly taking on a substantial business in a male dominated world. It would be nice to know more about her.

The early brick makers

The aforementioned Richard Sheppard who appears to have succeeded Mary as owner of the brick-yard does not appear on the 1841 census for Great Linford, nor indeed is there any clear sighting of him elsewhere, but we can see that three men in the village were then employed as brickmakers, presumably by him or his successors.

John Nichols was aged 50 and was born in 1791 in Great Linford. His wife was Kitty Daniell of Bletchley and at the time of the census they had a daughter and two sons. John worked at the brick kilns with his eldest son Thomas, then aged 25, Thomas was born in Bletchley in 1814 and in 1841 was living in Great Linford with his wife Ann and two sons.

William Jones, aged 35, was born in 1806 in nearby Newport Pagnell. At the time of the 1841 census he was living in Great Linford with his wife Ann and a son and daughter.

By 1851, John and Thomas Nichols had left the trade, John to become an agricultural labour and Thomas a Rail labourer. William Jones has returned to Newport Pagnell where he was working as a tile maker, but there were still two resident Brickmakers in Great Linford. William Reynolds and Benjamin Elliot were both 27-year-old natives of the village, married with children and resident on the High Street. Intriguingly, Benjamin was described as a “Brick and Tile Maker”, suggesting another trade was then established in the village.

There does exist one intriguing clue to a brick maker in the village, though what it might mean or even a date is presently entirely unknown. The picture following is of several in-situ bricks on the High Street. These appear to bear makers marks. Two bricks have an identical, presumably stamped logo, with the letters L and S. One brick additionally contains the initials W.H. Conceivably then we have a previously unknown brick making company with the initials L and S, and an individual brick maker with the initials W and H. Neither set of initials match any of the brick-making names presently known to be associated with the village, but given these are hand made bricks, it seems entirely plausible that they were made locally.

John Nichols was aged 50 and was born in 1791 in Great Linford. His wife was Kitty Daniell of Bletchley and at the time of the census they had a daughter and two sons. John worked at the brick kilns with his eldest son Thomas, then aged 25, Thomas was born in Bletchley in 1814 and in 1841 was living in Great Linford with his wife Ann and two sons.

William Jones, aged 35, was born in 1806 in nearby Newport Pagnell. At the time of the 1841 census he was living in Great Linford with his wife Ann and a son and daughter.

By 1851, John and Thomas Nichols had left the trade, John to become an agricultural labour and Thomas a Rail labourer. William Jones has returned to Newport Pagnell where he was working as a tile maker, but there were still two resident Brickmakers in Great Linford. William Reynolds and Benjamin Elliot were both 27-year-old natives of the village, married with children and resident on the High Street. Intriguingly, Benjamin was described as a “Brick and Tile Maker”, suggesting another trade was then established in the village.

There does exist one intriguing clue to a brick maker in the village, though what it might mean or even a date is presently entirely unknown. The picture following is of several in-situ bricks on the High Street. These appear to bear makers marks. Two bricks have an identical, presumably stamped logo, with the letters L and S. One brick additionally contains the initials W.H. Conceivably then we have a previously unknown brick making company with the initials L and S, and an individual brick maker with the initials W and H. Neither set of initials match any of the brick-making names presently known to be associated with the village, but given these are hand made bricks, it seems entirely plausible that they were made locally.

The decline of brick making

Perhaps rather tellingly if the smaller brickyards were succumbing to commercial pressures, by the time of the 1861 census there were no brick makers (or indeed tile makers) to be found in the village, though there were now four brick layers. The vagaries of the census records may mean they might have simply been recorded as “labourers”, but it seems more likely that the brick kilns at the Wharf had closed, either out-competed by both canal and railway commerce or perhaps the adjacent clay reserves had become played out? With 4 brick layers on hand, there was clearly a ready source of bricks and a demand for their use, but these raw materials were likely coming from elsewhere in the county.

Moving on to the 1871 census, we find one bricklayer and one bricklayers assistant. In 1881 there are three bricklayers, one of whom is retired, and though we again find a few bricklayers in 1891, there is no sign that anyone is making bricks locally.

Moving on to the 1871 census, we find one bricklayer and one bricklayers assistant. In 1881 there are three bricklayers, one of whom is retired, and though we again find a few bricklayers in 1891, there is no sign that anyone is making bricks locally.

New brick kilns at Great Linford

Building the brick kilns at Great Linford

Building the brick kilns at Great Linford

In 1895 the brickmaking industry was restored to Great Linford, the legacy of which is preserved by the two surviving kilns still to be found today in the parish. The kilns and the clay pits that supplied them were built, owned and operated by a George Osborn Price, a corn merchant who seems to have branched out into any number of trades. The 1899 Kelly’s Trade Directory describes him as a corn, cake, coal & lime merchant & brick maker, as well as an agent for Webb’s seeds and Proctor & Ryland’s manures. He lived at The Green in Newport Pagnell and died on July 29th 1905 (he was sufficiently prominent in the community to have a memorial inside St. Peter’s & St. Pauls church in Newport Pagnell), whereupon his son John continued the business.

Exactly when and for how long the kilns operated is not readily apparent, but the 1901 census lists a John Thornton Read as foreman of the brickyards, and he is still there in the Brickyard Cottage in 1911. John was born in Fringford, Oxfordshire into a brickmaking family. His father, also a John Thornton Read, was a foreman in a number of brick works in several counties and his son followed in his footsteps, arriving in Great Linford sometime around 1895. We know this because his daughter Ruth was born in Great Linford around the 3rd quarter of that year, so presuming he was employed to bring the new brick yard into operation, it must have been established sometime between 1891 and 1895.

Exactly when and for how long the kilns operated is not readily apparent, but the 1901 census lists a John Thornton Read as foreman of the brickyards, and he is still there in the Brickyard Cottage in 1911. John was born in Fringford, Oxfordshire into a brickmaking family. His father, also a John Thornton Read, was a foreman in a number of brick works in several counties and his son followed in his footsteps, arriving in Great Linford sometime around 1895. We know this because his daughter Ruth was born in Great Linford around the 3rd quarter of that year, so presuming he was employed to bring the new brick yard into operation, it must have been established sometime between 1891 and 1895.

Back-breaking work

An article carried in the Bucks Standard of June 22nd, 1957 provides a detailed account of life as a brick-worker, part of which is here reproduced, along with a picture of the men taken in the late 1880s.

It was hard, gruelling work, where clothes soon became saturated with sweat, and respites were few. Sabotaging machines for a few minutes to ease aching backs was not unknown.

The work was done by a small gang of men. There was those in the clay pit, digging and hauling the raw material to the “plug,” a machine that beat and stirred the clay and fed it in one continuous strip through a die.

A man fed the “plug” and the next job was “cutting off.” This was the hardest task of all. Bent almost double a man had to oil a small “table” to prevent the clay sticking, cut off the required length and then pull down a wire to cut six bricks. These wet bricks weighed anything up to half a hundredweight and still bent double, the “cutter-off” had to lift them onto a barrow (there is one in the picture) ready for the “runner-away” to wheel them at top speed to a series of duckboards where they were arranged by the "setter-down”" to dry.

For all that work the six man gang got 3 shillings a 1,000 bricks for making, another 3 shillings for wheeling away and setting down in the kilns, and 10d a 1,000 for fetching them out when baked. Six a.m. to 6.30p.m were regular hours and the men were very lucky to go home at the end of the day with 22 shillings.

Most of the clay pit work was done in the winger months and the bricks were made in warmer weather. The rate for clay digging was 3½d an hour, and there was the hazard of wheeling great barrow-loads of heavy clay up icy nine-inch planks out of the pits to the “plug.”

When the kiln was filled with between 25,000 and 30,000 bricks, earth was placed over the top and fires lit in the five fire-holes round the sides. It was then the job of the man who lived at the brickyard cottage, Jack Read, to see that these fires were kept in and not allowed to go out until the bricks were ready.

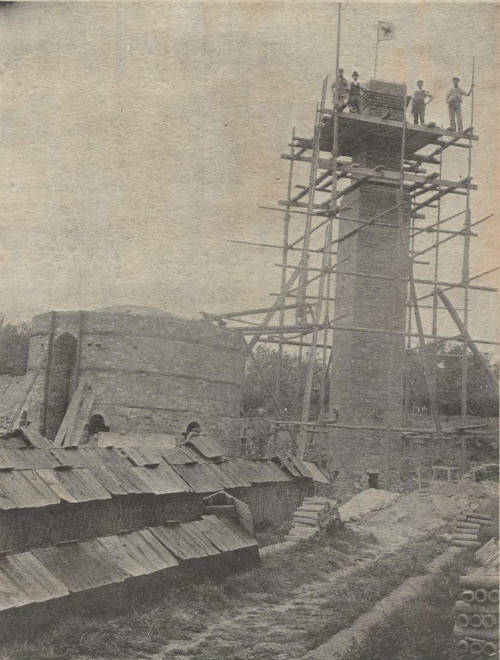

Alongside the Bucks Standard, the Milton Keynes Gazette Newspaper of January 14th 1977 also carried an extensive article on brick making in the area alongside a photograph of the kilns (sadly undated) under construction. From both articles, we can name quite a few of the men who worked at the pits. We learn that the aforementioned Jack Read was christened John, and that far more colourful nicknames were all the vogue for these men. Hence we have, “Dabber” Riley, “Boxer” Riley, “Joey” Jenkins, “Captain” Guidewell, “Toddler” Mills and “Hookey” Keech. Other names associated with the kilns at Great Linford were Arthur Moseley, Tomey Lacey, who also kept the Wharf Inn, Jack Haley, Bill Reynolds, Bill Burnell, George Burnell, Jim Burnell (surely all related), Sammy Yarrington, Jack Carvill and Albert Stonton.

Many of these men lived elsewhere than Great Linford, and only “Hookey” Keech can be reasonably identified as a village resident, most likely being Thomas Keech, 22 years of age on the 1901 census for Great Linford, but born at Newport Pagnell. One other name we can identity is that of Joe Malshar, identified on the old information board erected at the kilns as the “Engine Driver”, a fact corroborated by a census record for 1911 for Newport Pagnell which lists a Joseph Malshar, aged 55, as a “Gas engine attendant.” This gives an interesting insight into the power source at the kilns. The Great Linford kilns were said to be one of the most modern in the country at the time, and the use of a gas engine to power the machinery to grind and mix the clay would certainly have put it into this category; the Battleground Brick Works in Gloucestershire claimed in 1893 to have the first gas engine used for brick making in the country, so Great Linford was clearly one of the very early adopters of this technology. The steam engine at Great Linford can be glimpsed in the photograph reproduced above.

Unfortunately modern or not, the kilns are thought to have closed shortly after 1911, likely because the advent of much more economical continuous firing kilns and traction engine transport made it cheaper to bring in bulk shipments of bricks from Newton Longville, where “Jack” Read had worked prior to his employment at Great Linford, but nonetheless, at the height of its operations, upwards of 20,000 bricks at a time were transported from the kilns at Great Linford to Wolverton, Castlethorpe and Cosgrove. The Milton Keynes Gazette article names a Bill Lightfoot as one the bargemen, though he would have just one among many who plied a trade along the canal.

Many of these men lived elsewhere than Great Linford, and only “Hookey” Keech can be reasonably identified as a village resident, most likely being Thomas Keech, 22 years of age on the 1901 census for Great Linford, but born at Newport Pagnell. One other name we can identity is that of Joe Malshar, identified on the old information board erected at the kilns as the “Engine Driver”, a fact corroborated by a census record for 1911 for Newport Pagnell which lists a Joseph Malshar, aged 55, as a “Gas engine attendant.” This gives an interesting insight into the power source at the kilns. The Great Linford kilns were said to be one of the most modern in the country at the time, and the use of a gas engine to power the machinery to grind and mix the clay would certainly have put it into this category; the Battleground Brick Works in Gloucestershire claimed in 1893 to have the first gas engine used for brick making in the country, so Great Linford was clearly one of the very early adopters of this technology. The steam engine at Great Linford can be glimpsed in the photograph reproduced above.

Unfortunately modern or not, the kilns are thought to have closed shortly after 1911, likely because the advent of much more economical continuous firing kilns and traction engine transport made it cheaper to bring in bulk shipments of bricks from Newton Longville, where “Jack” Read had worked prior to his employment at Great Linford, but nonetheless, at the height of its operations, upwards of 20,000 bricks at a time were transported from the kilns at Great Linford to Wolverton, Castlethorpe and Cosgrove. The Milton Keynes Gazette article names a Bill Lightfoot as one the bargemen, though he would have just one among many who plied a trade along the canal.