Kizby and Kezia Rainbow

|

Kizby (also spelt Kisby) Rainbow was born in the village of Sherington, Buckinghamshire toward the end of April 1864. His parents were William Rainbow and Rachel Boon. William was a Malster, someone who prepared grain for the use of a brewer of beer. By the time of the 1881 census the family have relocated from Sherington to Newport Pagnell, and Kizby is following in his father’s footsteps as a Malster. But by 1891 Kizby has changed profession, though not trade, having secured a job as a stationary engine driver at a brewery, which certainly sounds like a good upwards move to a skilled position. Kizby is now also a family man, having married Kezia Roberts in 1883. Kezia had been born in Newport Pagnell in 1866 and was named after her grandmother. Kizby and Kezia would go on to have 8 chilldren, though tragedy had struck in 1898 with the loss of their 8 year old son Charles Albert. But all seems relatively well by the 1901 census, with Kizby continuing to be employed in a brewery in Newport Pagnell, though he is now described as a labourer rather than an engine driver.

However by the time of the 1911 census their relative good fortune seems to have completely unravelled, with disturbing evidence that the family is in disarray. It is at this time that we find Kezia without her husband in Great Linford, cohabitating with her mother Elizabeth in a dwelling in Shop Yard. This would have been an area just off the High Street, likely to have been adjacent to the house now known as The Old Post Office. Elizabeth had only just recently remarried, having lost her husband John in 1909. Her new husband was William Haynes. Also in the household is Kezia’s second son William, aged 24, and her 1 year old son Percy. But where are the rest of her family? |

Newport Pagnell Workhouse

Unfortunately we find 3 of the children in the very worst of circumstances, inmates of the Newport Pagnell workhouse. Jim, aged 12, Fanny Elizabeth, aged 10 and Stanley Charles, aged 6 are all listed together on the 1911 census. But where was Kizby? Tragically, he was in the same place, listed on a separate sheet of the census. Unfortunately this separation on paper was an accurate reflection of the harsh regime of the workhouse, as physically removing children from their parents was considered a kindness, as in the eyes of the authorities, by the very act of entering the workhouse, the parents had proven themselves a poor role model for their children.

What exactly had happened to cause the family’s downfall we will likely never know, but one has to suspect that hard decisions had been made by Kizby and Kezia, and that by sending Kezia to live with her mother in Great Linford, it at least kept her and their babe in arms out of the workhouse.

What exactly had happened to cause the family’s downfall we will likely never know, but one has to suspect that hard decisions had been made by Kizby and Kezia, and that by sending Kezia to live with her mother in Great Linford, it at least kept her and their babe in arms out of the workhouse.

The family reunited

Thankfully within a few years, we begin to pick up signs that the family have been reunited in better circumstances. In 1913, Fanny Elizabeth receives an honourable mention in the Northampton Mercury newspaper of March 28th, for good attendance at Great Linford School. We also know that Kizby had escaped the workhouse and found employment, though the evidence for this is somewhat less admirable, as in late December of 1914, we find him brought before the Petty Sessions at Newport Pagnell for having left a horse and cart unattended and without control. He was fined 1 shilling for his transgression.

On December 12th, 1913, a George Rainbow of Great Linford, whom we must suspect to be Francis George Rainbow, 4th son of Kizby and Kezia, was brought before the Newport Pagnell County Court accused of not paying a medical bill of 6 shillings to a Doctor Miles. Despite his protestations that he was poor man on 17 shillings a week, he was ordered to make payment of 3 shillings per week.

On December 12th, 1913, a George Rainbow of Great Linford, whom we must suspect to be Francis George Rainbow, 4th son of Kizby and Kezia, was brought before the Newport Pagnell County Court accused of not paying a medical bill of 6 shillings to a Doctor Miles. Despite his protestations that he was poor man on 17 shillings a week, he was ordered to make payment of 3 shillings per week.

Trouble with the courts

It turns out that Kezia also had a number of run-ins with the authorities, with the inference being that she had something of a fiery personality. Kezia (spelt Keziah in the report) was summonsed on September 24th, 1913 to answer a charge of having assaulted a woman named Clara Jenkins. Clara alleged that her clothes line had been cut down and she believed Kezia was the culprit. In the ensuing confrontation tempers flared, words were exchanged and Jenkin’s claimed that Kezia had struck her, though a witness subsequently testified that Jenkins had thrown bricks at Kezia. The judge seemed to be used to dealing with these kind of intractable disputes, and with a great deal of patience on display, attempted to mollify the woman and encourage a rapprochement. Neither seemed particularly keen to bury the hatchet, and it took the threat of a fine for both before there was a grudging hand shake, and then with some “inaudible remarks” both women left the court.

In mitigation, if Kezia was still living in the area known as Shop Yard, it is likely to have been a cramped space with little room to move; in 1911, there were 5 households in the yard, containing a total of 19 persons! Plenty of opportunity then for frictions to arise, especially on wash day, which for women still lacking the appliances and conveniences we enjoy today, was a task requiring considerable time and energy. It is not hard to imagine that a dispute over precious drying space could have escalated out of hand.

At least one of the yards in Great Linford did seem to have a reputation as an unpleasant place to live, such that in 1905, the Rural District Council Sanitary Committee were embroiled in a disagreement with the Uthwatts over the poor condition of toilets and drainage in Chapel Yard, a little further up the High Street from Shop Yard.

Kezia was back in court in June of 1916, but as a witness to the prosecution in a long running case that had captured the public imagination. Emily Maud Tysoe, a widow, was accused of neglecting her 3 children; her husband having lost his life in the war the previous year, while at the same time, the family had faced eviction from their home in Haversham. The plight of the Tysoes had prompted questions in parliament, but had not stopped the eviction, and Emily had fetched up in Great Linford. Since Kezia is described in the proceedings as a neighbour, it seems likely that the alleged neglect occurred in Shop Yard. Kezia gave evidence as to the condition of the Tysoe children.

On Wednesday August 3rd, 1921, Kezia was back in the dock herself, this time accused by a Mrs Atkinson of the High Street of using “obscene and indecent language.” A written transcript was handed to the bench, whereupon the presiding judge described it, one imagines in a somewhat weary voice, as “the usual Buckinghamshire Police Court language.” An Annie Susan Jenkins (a surname familiar from the previous case and perhaps hinting at a continuing feud) gave evidence in support of the accuser, and this time Kezia found herself bound over to keep the peace and fined what must have been the seriously large sum of £5, plus 5 shillings, 6p in costs.

In mitigation, if Kezia was still living in the area known as Shop Yard, it is likely to have been a cramped space with little room to move; in 1911, there were 5 households in the yard, containing a total of 19 persons! Plenty of opportunity then for frictions to arise, especially on wash day, which for women still lacking the appliances and conveniences we enjoy today, was a task requiring considerable time and energy. It is not hard to imagine that a dispute over precious drying space could have escalated out of hand.

At least one of the yards in Great Linford did seem to have a reputation as an unpleasant place to live, such that in 1905, the Rural District Council Sanitary Committee were embroiled in a disagreement with the Uthwatts over the poor condition of toilets and drainage in Chapel Yard, a little further up the High Street from Shop Yard.

Kezia was back in court in June of 1916, but as a witness to the prosecution in a long running case that had captured the public imagination. Emily Maud Tysoe, a widow, was accused of neglecting her 3 children; her husband having lost his life in the war the previous year, while at the same time, the family had faced eviction from their home in Haversham. The plight of the Tysoes had prompted questions in parliament, but had not stopped the eviction, and Emily had fetched up in Great Linford. Since Kezia is described in the proceedings as a neighbour, it seems likely that the alleged neglect occurred in Shop Yard. Kezia gave evidence as to the condition of the Tysoe children.

On Wednesday August 3rd, 1921, Kezia was back in the dock herself, this time accused by a Mrs Atkinson of the High Street of using “obscene and indecent language.” A written transcript was handed to the bench, whereupon the presiding judge described it, one imagines in a somewhat weary voice, as “the usual Buckinghamshire Police Court language.” An Annie Susan Jenkins (a surname familiar from the previous case and perhaps hinting at a continuing feud) gave evidence in support of the accuser, and this time Kezia found herself bound over to keep the peace and fined what must have been the seriously large sum of £5, plus 5 shillings, 6p in costs.

Kezia finds a home in an Almshouse

Meanwhile, one by one the Rainbow children had drifted away from Great Linford to begin lives of their own, with some settling in the village of Bugbrooke in Northamptonshire, but the electoral registers provide some excellent insights into the continuing presence of the remaining Rainbow family in Great Linford. From 1918 through to 1926 we find both Kizby and Kezia listed as living on the western side of the High Street; Shop Yard would have been on the western side of the street, and though it is not named in any of the electoral rolls, various newspaper accounts suggest it was still a distinct place in the village until at least the early 1940s.

Their son Jim is listed separately from 1918 to 1921, also on the western side of the High Street, suggesting he was now living on his own. He married in Oxfordshire in 1921, which appeared to mark his departure from the village. Another son, William John, is also listed at a separate address known as Penny’s Yard between 1918 and 1919; he married in 1920 in West Dulwich, which marks the departure of the last of the Rainbow children from the village, leaving just Kizby and Kezia.

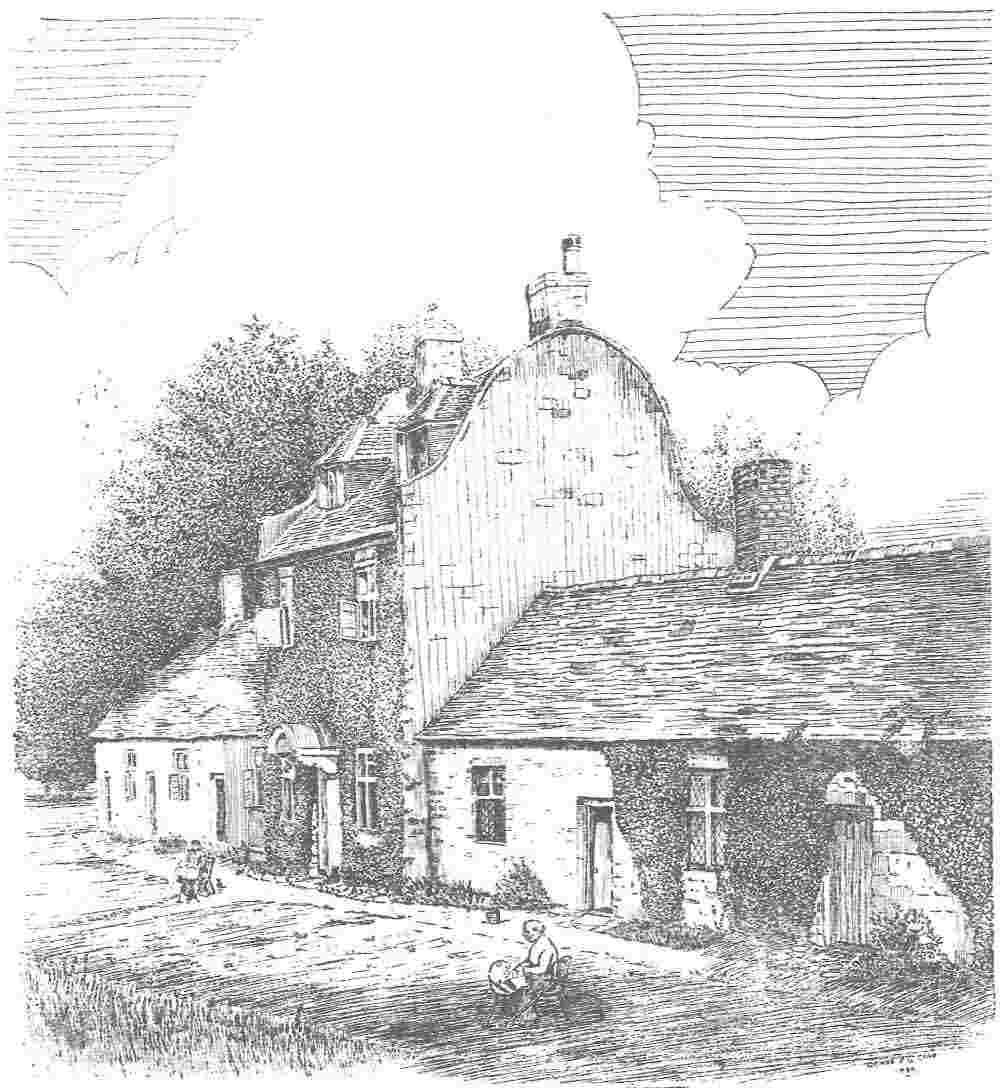

Kizby passed away in 1926 at the age of 62 and from the electoral registers we find that by the following year Kezia had found a new home at the village Almshouses, located in Great Linford Manor Park. The Almshouses had been built at the very beginning of the 1700s by the then lord of the manor, Sir William Prichard, to serve as homes for the poor. Kezia would stay here for most of the rest of her life – we find her recorded there for instance in the document known as the 1939 Register, a national survey conducted on the eve of the Second World War.

Their son Jim is listed separately from 1918 to 1921, also on the western side of the High Street, suggesting he was now living on his own. He married in Oxfordshire in 1921, which appeared to mark his departure from the village. Another son, William John, is also listed at a separate address known as Penny’s Yard between 1918 and 1919; he married in 1920 in West Dulwich, which marks the departure of the last of the Rainbow children from the village, leaving just Kizby and Kezia.

Kizby passed away in 1926 at the age of 62 and from the electoral registers we find that by the following year Kezia had found a new home at the village Almshouses, located in Great Linford Manor Park. The Almshouses had been built at the very beginning of the 1700s by the then lord of the manor, Sir William Prichard, to serve as homes for the poor. Kezia would stay here for most of the rest of her life – we find her recorded there for instance in the document known as the 1939 Register, a national survey conducted on the eve of the Second World War.

Life in the Almshouse

With the kind permission of the family, the following is a first-hand account of Kezia’s life in her Almshouse.

Kisby (Grandad Rainbow) died about 1926, leaving gran to spend most of her later years in Great Linford, in a small compact almshouse; being in a row of six homes for elderly people.

Her home consisted of a kitchen with no taps for water. One had to take a bucket to a well in the garden. No gas or electric just oil lamps, and a quick sprint up the garden path to the toilet. Into a very large room which was bedroom, sitting room and kitchen all rolled into one. The up to date term would be open plan living. One corner had a huge four-poster bed, a solid wooden top and the sides curtained off with heavy curtains. I wonder how many of we grandchildren played hide and seek in that secret place.

Then large windows and wooden shutters and window seats, and on the other side of the room was a big blackfire with ovens one each side and a chain hanging over the fire with a hook to put the kettle to boil.

Gran, who was quiet old fashioned and always wore long black skirts and jumpers and a long pinafore. She had long black coats and Edwardian type hats, while her hair was combed into a bun at the nave of her neck. To earn a little money she made exquisite pillow lace which was sent to London posh folks, for edging tablecloth's, baby clothes and dresses. Using a pillow! She had dozens of wooden or bone bobbins weaving silk thread to form patterns, and we would gaze in wonder at the speed of those nimble fingers.

So this was a special place and there was great excitement when my mother (daughter in law. Jim’s wife.!) and Aunt Fan went to see Gran. Did we go from Bugbrooke by road? Oh no, not when we could travel free on the train, being Railway children. So on the bus to Northampton Castle station, hop on a train to Wolverton and then on the Puffy Billy to Great Linford. Now, there was only one rail track, so, the engine pulled the coaches one way, and the pushed them all back again on the return journey.

Nearing Linford we could look across the fields to see Gran waving from her doorway.

Because of the unique location, it was always exciting. We had to pass through an iron gated road to reach this small row of houses, which stood on a gentle rise overlooking a beautiful lake. On a sunny day we children used to sit on that grassy bank and feed the hordes of ducks (magic).

The road continued between the slope and the lake to the church. So it was here we would go to put flowers on Pap's grave.

These visits went on until Gran could no longer care for herself. She then made her home with Aunt Fan at Bugbrooke who cared for her until she passed away.

Kezia passed away at the age of 76 in 1942.