The Wharf Inn, Great Linford

The first reference to The Wharf Inn can be found in the records of licensed innkeepers for the Newport Three Hundred (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X-423/9), the administrative region that included Great Linford. Oddly, the pub is never referred to as “The Wharf Inn” in these documents, but instead is consistently referred to as “The Linford Inn.” However, it is undoubtedly the same public house, as we can match the names of publicans with other contemporaneous records that do clearly refer to it as The Wharf Inn. Why there should be such a marked discrepancy between the licensing records and the name commonly offered in other sources is yet to be adequately explained, though during its history we also find it periodically named as the "Linford Wharf Inn" and "Great Linford Wharf Inn."

As an integral part of the wharf facilites for the Grand Junction Canal, which was cut through the parish in 1800, a reasonable presumption would be that the inn was built and financed by the canal company. This may indeed be the case, but as will become evident from available records, from at least 1808, the entirety of the wharf, including the inn, appears to have been owned by Henry Uthwatt, the Lord of Great Linford manor. There is a certain irony to this, as Henry had raged against the canal company for smashing through his pleasure gardens. But it seems that when push came to shove, the old adage, if you can't beat them, join them, (especially if there was money to be made) had caused a change of heart.

A brief description of The Wharf Inn is offered in the book A Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes (1986, Paul Woodfield, Milton Keynes Development Corporation.)

As an integral part of the wharf facilites for the Grand Junction Canal, which was cut through the parish in 1800, a reasonable presumption would be that the inn was built and financed by the canal company. This may indeed be the case, but as will become evident from available records, from at least 1808, the entirety of the wharf, including the inn, appears to have been owned by Henry Uthwatt, the Lord of Great Linford manor. There is a certain irony to this, as Henry had raged against the canal company for smashing through his pleasure gardens. But it seems that when push came to shove, the old adage, if you can't beat them, join them, (especially if there was money to be made) had caused a change of heart.

A brief description of The Wharf Inn is offered in the book A Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes (1986, Paul Woodfield, Milton Keynes Development Corporation.)

An inn, of the last years of the 18th century built to serve canal traffic. Colourwashed stone and a tiled roof. Three stories but two facing the canal. Three bays with central door to hallway and 16 pane sashes. Lean-to against the west gable.

The lean-to has since been demolished, and the colourwash removed to expose the natural brick surface of the walls. The building is now a private residence.

Josiah Denny Roote

Though the above description dates the building to the “last years of the 18th century”, The Wharf Inn appears to have opened for business circa 1802, with its first landlord identified in the licensing records as Josiah Denny Roote; certainly a rare name, though not quite as easy to trace as might be hoped. However, available evidence points toward a date of birth of November 15th, 1761, at Drayton, Oxfordshire. His mother was Elizabeth Denny and his father Thomas was a weaver. Josiah’s formative years are not recorded, but a Josiah Roote can be found living in London in the late 1780s. Frustratingly, Josiah seemed loathe to provide his middle name to officials, but we can be reasonably confident that the Josiah Roote who married an Elizabeth Pardoe at St. Mary, Whitechapel on November 30th, 1790, is almost certainly the Josiah Denny Roote who arrived at Great Linford circa 1802. Interestingly, he is noted in the marriage record as a widower, but the identity of his first wife is uncertain.

Josiah and Elizabeth had at least three children, two sons, Ambrose (1791) and William (1793) in London, and a daughter Elizabeth in Bloxham, Oxfordshire in 1803. We can imagine that the curate who wrote the baptism record for Elizabeth must have been a stickler for detail, as he managed to extract Josiah’s middle name, and added the additional observation that the mother, Elizabeth, was from London.

Exactly why Josiah and a pregnant Elizabeth should have been in Bloxham in 1803 when it is quite clear they were connected to The Wharf Inn is unknown, though this does roughly coincide with a period of turmoil for the couple, as in 1799 the London Gazette of March 26th was reporting bankruptcy proceedings against a Josiah Roote. This notice identifes him as a Linen-Draper, Dealer and Chapman; the latter is a somewhat opaque term that can mean an itinerant dealer or hawker.

Unsurprisingly for a pub so closely associated with the comings and goings on the canal, we find evidence of The Wharf Inn serving as the venue for commercial activities. The Northampton Mercury of April 2nd, 1803, provides an early example, with the notification that, “two substantial well built boats” were in the basin at Great Linford and would be auctioned at the inn on April 13th at twelve o’clock.

In 1808, an indenture (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X_2228) was drawn up by Henry Uthwatt, which itemises in great detail his land and property holdings and the names of his tenants. including Josiah Denny Roote, who is noted as occupying The Wharf Inn. As observed previously, the licensing records, including the entry for 1808, names Josiah as the landlord of the Linford Inn, but here we have a very convincing piece of evidence proving that the two named establishments are indeed one and the same. This document also clearly establishes that the Uthwatts held a pecuniary interest in the Wharf Inn (and the Wharf), which is hardly surprising given the level of control they exerted over the entire parish.

Josiah meanwhile remained as publican of The Wharf Inn until circa 1809/10, before he moved on to Husborn Crawley in Bedfordshire, becoming the landlord there of The White Horse. Josiah was still at this pub when he died at the age of 75 in late 1835.

Josiah and Elizabeth had at least three children, two sons, Ambrose (1791) and William (1793) in London, and a daughter Elizabeth in Bloxham, Oxfordshire in 1803. We can imagine that the curate who wrote the baptism record for Elizabeth must have been a stickler for detail, as he managed to extract Josiah’s middle name, and added the additional observation that the mother, Elizabeth, was from London.

Exactly why Josiah and a pregnant Elizabeth should have been in Bloxham in 1803 when it is quite clear they were connected to The Wharf Inn is unknown, though this does roughly coincide with a period of turmoil for the couple, as in 1799 the London Gazette of March 26th was reporting bankruptcy proceedings against a Josiah Roote. This notice identifes him as a Linen-Draper, Dealer and Chapman; the latter is a somewhat opaque term that can mean an itinerant dealer or hawker.

Unsurprisingly for a pub so closely associated with the comings and goings on the canal, we find evidence of The Wharf Inn serving as the venue for commercial activities. The Northampton Mercury of April 2nd, 1803, provides an early example, with the notification that, “two substantial well built boats” were in the basin at Great Linford and would be auctioned at the inn on April 13th at twelve o’clock.

In 1808, an indenture (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X_2228) was drawn up by Henry Uthwatt, which itemises in great detail his land and property holdings and the names of his tenants. including Josiah Denny Roote, who is noted as occupying The Wharf Inn. As observed previously, the licensing records, including the entry for 1808, names Josiah as the landlord of the Linford Inn, but here we have a very convincing piece of evidence proving that the two named establishments are indeed one and the same. This document also clearly establishes that the Uthwatts held a pecuniary interest in the Wharf Inn (and the Wharf), which is hardly surprising given the level of control they exerted over the entire parish.

Josiah meanwhile remained as publican of The Wharf Inn until circa 1809/10, before he moved on to Husborn Crawley in Bedfordshire, becoming the landlord there of The White Horse. Josiah was still at this pub when he died at the age of 75 in late 1835.

William and Susanne Goodman

By 1810, the licensing records show the new publican to be William Goodman. There are sporadic instances of the name Goodman in Great Linford parish records dating back to 1627, so it may be that William was part of a family with deep roots in the parish, but no baptism in the village is apparent for him specifically, and there are several persons of the same name born in other Buckinghamshire villages who could easily be him, as well as evidence of Goodmans living in the nearby town of Newport Pagnell. Suffice to say, it is a relatively common name in the locality.

We can calculate from the parish record of his burial on October 20th, 1813 aged 33 that he was born around 1780 and we can also pinpoint a marriage, to a Susanne Sharman (or Sherman) on April 24th, 1898, in Newport Pagnell. He and Susanne appear to have had three children, Mary born 1805 in Newport Pagnell and Samuel (1811) and James (1813) who were almost certainly born at The Wharf Inn. Their baptism records reveal that William and his wife were nonconformists, worshipping outside the mainstream Church of England, which is not surprising as Newport Pagnell was a hotbed of religious dissent, and even Great Linford would in due course gain an independent chapel.

A document entitled an Appointment upon trust for sale (Buckinghamshire Archives D/U/1/26), dated 1811, continues to place the inn (and the wharf and its warehouses) in the ownership of Henry Uthwatt, but with the entirety tenanted by a William and Ralph Wilson. The origin of these two persons and their precise place in the history of the inn and wharf is at present unknown, but we might presume that William Goodman was a sub-tenant of the latter two men. However, change was afoot. Continuing to follow the paper trail, a document held at Buckinghamshire Archives (D/U/1/64) reveals that in 1815 the Uthwatts had sold The Wharf Inn along with 80 acres of land to the Newport Pagnell Canal Company.

William’s Goodman's death on October 16th, 1813, at a such a young age as 33 must have been a considerable blow to his wife; tragically he had passed away just months after the birth of their son James, but landlord’s wives are made of redoubtable stuff, and Susanne promptly stepped into William’s shoes to take over the license, a fact borne out by her inclusion in the licensing records until 1815. She was likely able to do this by application of a legal conveyance device called copyhold, which bestowed the right for a lease to pass over to an heir. However, on May 7th, 1816, Susanne was remarried, to a Thomas Albright, and one can only wonder if she was stoically accepting of the fact that her new husband was then listed as the licensee in her stead.

It appears the couple had at least one daughter together, Eliza, baptised November 24th, 1816, at Great Linford, which given the date of their marriage, may have raised some eyebrows in the village. There was also a considerable difference in ages, with Thomas some 20 years her junior. Of course it may well have been a love match, but equally, it is hard to shake the suspicion that marrying Susanne was a smart move for Thomas. This is of course pure supposition. Thomas was removed or gave up the license in circa 1818, with the family relocated to Newport Pagnell by the time of the 1841 census. Thomas was then described as a cotton dealer.

We can calculate from the parish record of his burial on October 20th, 1813 aged 33 that he was born around 1780 and we can also pinpoint a marriage, to a Susanne Sharman (or Sherman) on April 24th, 1898, in Newport Pagnell. He and Susanne appear to have had three children, Mary born 1805 in Newport Pagnell and Samuel (1811) and James (1813) who were almost certainly born at The Wharf Inn. Their baptism records reveal that William and his wife were nonconformists, worshipping outside the mainstream Church of England, which is not surprising as Newport Pagnell was a hotbed of religious dissent, and even Great Linford would in due course gain an independent chapel.

A document entitled an Appointment upon trust for sale (Buckinghamshire Archives D/U/1/26), dated 1811, continues to place the inn (and the wharf and its warehouses) in the ownership of Henry Uthwatt, but with the entirety tenanted by a William and Ralph Wilson. The origin of these two persons and their precise place in the history of the inn and wharf is at present unknown, but we might presume that William Goodman was a sub-tenant of the latter two men. However, change was afoot. Continuing to follow the paper trail, a document held at Buckinghamshire Archives (D/U/1/64) reveals that in 1815 the Uthwatts had sold The Wharf Inn along with 80 acres of land to the Newport Pagnell Canal Company.

William’s Goodman's death on October 16th, 1813, at a such a young age as 33 must have been a considerable blow to his wife; tragically he had passed away just months after the birth of their son James, but landlord’s wives are made of redoubtable stuff, and Susanne promptly stepped into William’s shoes to take over the license, a fact borne out by her inclusion in the licensing records until 1815. She was likely able to do this by application of a legal conveyance device called copyhold, which bestowed the right for a lease to pass over to an heir. However, on May 7th, 1816, Susanne was remarried, to a Thomas Albright, and one can only wonder if she was stoically accepting of the fact that her new husband was then listed as the licensee in her stead.

It appears the couple had at least one daughter together, Eliza, baptised November 24th, 1816, at Great Linford, which given the date of their marriage, may have raised some eyebrows in the village. There was also a considerable difference in ages, with Thomas some 20 years her junior. Of course it may well have been a love match, but equally, it is hard to shake the suspicion that marrying Susanne was a smart move for Thomas. This is of course pure supposition. Thomas was removed or gave up the license in circa 1818, with the family relocated to Newport Pagnell by the time of the 1841 census. Thomas was then described as a cotton dealer.

James Hawley

Turning back to the licensing records, we find that in 1818 we have a new publican in place called James Hawley, the younger. This useful qualification to his name strongly suggests that he was the James born in Great Linford to James and Elizabeth Hawley in 1784. The Hawley family were prominent residents of the village; James Hawley senior was a farmer, making his home at the house on the High Street now known as The Cottage.

James the younger may have had a previous career as a baker in Cambridgeshire, but there is a cloud over his return to Great Linford, as in December 1813, a James Hawley, “formerly of Huntingdon, but late of Great Linford", is to be found languishing in debtor’s prison in Aylesbury. A little less than a year previously, the Cambridge Chronicle and Journal of February 26th, 1813, had announced that a house and bakehouse at Huntingdon and then in the occupation of James Hawley was to be offered for sale by auction. Perhaps he returned to Great Linford with creditors hot on his heels.

In December 1819 we find the “Great Linford Wharf Inn” up for sale by auction, described in the occupation of Mr James Hawley, the same year he is listed in the licensing records as the landlord of the “Linford Inn.” The advert carried in the Northampton Mercury of the 11th, describes the inn as coming with “an excellent yard, garden, stables, outbuildings and appurtenances, containing together, by estimation, one acre (more of less.)”

Annoyingly the advertisement does not tell us who the seller is, but we can presume it to have been the canal company. Intriguingly, it is stipulated that the inn is not intended to be sold or continued as a public house. The suspicion is that the pub failed to sell and the provision was dropped, as we continue to find James listed as the publican of The Wharf Inn in the license records until 1823, when these records cease.

The next reference to the Wharf Inn does not come until 1835 (Northampton Mercury, August 8th) and relates only to a sale held at the inn of an adjacent house and land, likely to be the dwelling now known as Canal Cottage. A newspaper advert addressed to "brewers, maltsters and others" carried in the Northampton Mercury of February 20th, 1836, tells us that The Wharf Inn was available to be let “for a term of years and entered upon on the 6th day of April next." We can speculate that James Hawley was the landlord departing, but in a now familiar pattern, it does not impart to us the identity of the owner.

By the time of the 1841 census, James Hawley and his wife Catherine, likely to be a Catherine Capon (possibly of Tingewick) have relocated to Bedford, where James had become a coal dealer. He was widowed in 1853, though he did subsequently return to Great Linford toward the end of his life, lodging with his sister Sophia on the High Street until his passing on November 11th, 1862.

In 1840, a tithe map (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) was produced for the parish, part of a country-wide imitative to simplify taxes levied by the church. The map and its index unfortunately do not make any distinction between the various buildings and facilities of the wharf, describing it as a "Public House, Gardens, Wharf and Basin", and numbering them all as 133. The owners are named as the Newport Pagnell Canal Company, seeming to confirm that the sale of 1819 had indeed fallen through, with the entirety of the facilities listed in the occupation of a John Rogers, Jesee Parsons, Edward Miller Mundy and “others.”

None of these men lived in Great Linford, but John Rogers and Jesse Parsons were co-owners of a brewery in Newport Pagnell, hence having an interest in The Wharf Inn seems entirely sensible. John Rogers was a doctor and Jesse Parsons was the son of a brewer from St. Albans and had married John’s sister. We might reasonably discount Edward Miller Mundy as the publican of The Wharf Inn, as available records describe him variously as a wheelwright and cooper, however it should be noted that it is not necessarily unusual to find publicans with second or even third jobs.

James the younger may have had a previous career as a baker in Cambridgeshire, but there is a cloud over his return to Great Linford, as in December 1813, a James Hawley, “formerly of Huntingdon, but late of Great Linford", is to be found languishing in debtor’s prison in Aylesbury. A little less than a year previously, the Cambridge Chronicle and Journal of February 26th, 1813, had announced that a house and bakehouse at Huntingdon and then in the occupation of James Hawley was to be offered for sale by auction. Perhaps he returned to Great Linford with creditors hot on his heels.

In December 1819 we find the “Great Linford Wharf Inn” up for sale by auction, described in the occupation of Mr James Hawley, the same year he is listed in the licensing records as the landlord of the “Linford Inn.” The advert carried in the Northampton Mercury of the 11th, describes the inn as coming with “an excellent yard, garden, stables, outbuildings and appurtenances, containing together, by estimation, one acre (more of less.)”

Annoyingly the advertisement does not tell us who the seller is, but we can presume it to have been the canal company. Intriguingly, it is stipulated that the inn is not intended to be sold or continued as a public house. The suspicion is that the pub failed to sell and the provision was dropped, as we continue to find James listed as the publican of The Wharf Inn in the license records until 1823, when these records cease.

The next reference to the Wharf Inn does not come until 1835 (Northampton Mercury, August 8th) and relates only to a sale held at the inn of an adjacent house and land, likely to be the dwelling now known as Canal Cottage. A newspaper advert addressed to "brewers, maltsters and others" carried in the Northampton Mercury of February 20th, 1836, tells us that The Wharf Inn was available to be let “for a term of years and entered upon on the 6th day of April next." We can speculate that James Hawley was the landlord departing, but in a now familiar pattern, it does not impart to us the identity of the owner.

By the time of the 1841 census, James Hawley and his wife Catherine, likely to be a Catherine Capon (possibly of Tingewick) have relocated to Bedford, where James had become a coal dealer. He was widowed in 1853, though he did subsequently return to Great Linford toward the end of his life, lodging with his sister Sophia on the High Street until his passing on November 11th, 1862.

In 1840, a tithe map (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) was produced for the parish, part of a country-wide imitative to simplify taxes levied by the church. The map and its index unfortunately do not make any distinction between the various buildings and facilities of the wharf, describing it as a "Public House, Gardens, Wharf and Basin", and numbering them all as 133. The owners are named as the Newport Pagnell Canal Company, seeming to confirm that the sale of 1819 had indeed fallen through, with the entirety of the facilities listed in the occupation of a John Rogers, Jesee Parsons, Edward Miller Mundy and “others.”

None of these men lived in Great Linford, but John Rogers and Jesse Parsons were co-owners of a brewery in Newport Pagnell, hence having an interest in The Wharf Inn seems entirely sensible. John Rogers was a doctor and Jesse Parsons was the son of a brewer from St. Albans and had married John’s sister. We might reasonably discount Edward Miller Mundy as the publican of The Wharf Inn, as available records describe him variously as a wheelwright and cooper, however it should be noted that it is not necessarily unusual to find publicans with second or even third jobs.

Conveniently concurrent with the publication of the tithe map, the country’s first national census was conducted in 1841, but this is a quite basic document, and in this case even when cross-referenced with the tithe map offers no help in identifying the incumbent landlord. The same year does offer up news that the entire wharf, including the inn was to be offered to let by auction, with the advertisement carried in the Northampton Mercury of February 6th. Lot 2, The Wharf Inn, is described as in full trade in the occupation of Messrs Parsons and Rogers, “or their under-tenant, under a lease, which will expire on the 6th of April next.”

It is fairly common for announcements of this sort to name the present occupier, but not so in this case, so the unnamed "under-tenant" remains elusive. It is striking that the pub is also described as a “free-house”, meaning it was not tied to a brewery and hence obliged to buy its beverages from a specific brewery. That we have already established that Parsons and Rogers were brewers does raise the interesting conundrum, who if not them was supplying The Wharf Inn with beer?

Amongst a bundle of deeds held at Buckinghamshire Archives (D-U/1/64) are references to the Taylor family and The Wharf Inn, including a deed of covenant dated 1845 from a William Faldo to a Mary Ann Taylor. A deed of covenant generally infers upon someone a duty to pay a regular amount of money. William Faldo was a builder with properties on the green at Newport Pagnell (and elsewhere) whilst Mary Ann Taylor appears on the 1840 Great Linford tithe map in the occupation of a house, garden, brickyard and close (number 132 on the above map), which can be pinpointed to the rear of the inn. To say that affairs concerning The Wharf Inn were complicated is something of an understatement.

It is fairly common for announcements of this sort to name the present occupier, but not so in this case, so the unnamed "under-tenant" remains elusive. It is striking that the pub is also described as a “free-house”, meaning it was not tied to a brewery and hence obliged to buy its beverages from a specific brewery. That we have already established that Parsons and Rogers were brewers does raise the interesting conundrum, who if not them was supplying The Wharf Inn with beer?

Amongst a bundle of deeds held at Buckinghamshire Archives (D-U/1/64) are references to the Taylor family and The Wharf Inn, including a deed of covenant dated 1845 from a William Faldo to a Mary Ann Taylor. A deed of covenant generally infers upon someone a duty to pay a regular amount of money. William Faldo was a builder with properties on the green at Newport Pagnell (and elsewhere) whilst Mary Ann Taylor appears on the 1840 Great Linford tithe map in the occupation of a house, garden, brickyard and close (number 132 on the above map), which can be pinpointed to the rear of the inn. To say that affairs concerning The Wharf Inn were complicated is something of an understatement.

John Warren

It is not until the 1851 census that we can positively identify another publican of The Wharf Inn, 32-year-old John Warren; it is likely he is misnamed as John Warner in an August 1851 news report pertaining to the approval of licenses. His father Daniel had come from nearby Little Woolstone and had married a Sarah Bird at Great Linford in 1811; the Birds were a significant family in the village.

By the time of the 1841 census, Daniel had established himself in the village as a tailor, with sons William and John following in his footsteps, but when the 1851 census was conducted, we find both brothers and a sister Elizabeth at The Wharf Inn, though William is recorded as continuing to work full time as a tailor. John had not quite abandoned the business either, as the Kelly’s trade directory of 1854 lists him as “Wharf Inn and tailor”, and in fact it seems tailoring was his true calling, as the 1861 census shows him still in the village, but once again working purely as a tailor. By contrast his brother William has become a full-time publican, though not at The Wharf Inn, but at the nearby Black Horse Inn. The Warrens are well represented in St. Andrew’s churchyard, with a number of gravestones surviving.

By the time of the 1841 census, Daniel had established himself in the village as a tailor, with sons William and John following in his footsteps, but when the 1851 census was conducted, we find both brothers and a sister Elizabeth at The Wharf Inn, though William is recorded as continuing to work full time as a tailor. John had not quite abandoned the business either, as the Kelly’s trade directory of 1854 lists him as “Wharf Inn and tailor”, and in fact it seems tailoring was his true calling, as the 1861 census shows him still in the village, but once again working purely as a tailor. By contrast his brother William has become a full-time publican, though not at The Wharf Inn, but at the nearby Black Horse Inn. The Warrens are well represented in St. Andrew’s churchyard, with a number of gravestones surviving.

Unjust measures

An advertisement carried in the Bedfordshire Mercury of February 3rd, 1855, announces that The Wharf Inn is available for let, which likely coincides with the departure of the Warrens, and indeed an Edwin Hackett was caught with unjust measures in December of 1856 (Bucks Herald, December 20th). Though his pub is not named, we know the names of the landlords at this time for The Nags Head and Black Horse, so Edwin looks very likely to have succeeded the Warrens at The Wharf Inn. Similarly, John Bradley, victualler of Great Linford was fined 16 shillings and six pence for serving unjust measures in 1859, (Bucks Herald, February 12th.) Again his pub is not named, but by logical elimination, we can say with some confidence that his pub was The Wharf Inn, a rather bad run of dodgy dealings.

George Atkins

The 1861 census gives us the name of a new publican at The Wharf Inn, 39-year-old George Atkins, originally from Leicester. His wife May, nee Hazlewood, was from the nearby village of Simpson. They married in 1855 and lived for a time in Stony Stratford, as two sons, George and Frederic and a daughter Flora, were all born there. Also listed in the census are a servant Sarah Housen and two boarders, Joseph Allen, an agricultural labourer, and Hilber Underwood, an engine fitter.

The census of 1861 was conducted on April 7th, so the Atkins must have arrived in Great Linford very shortly after the birth of two-month-old Flora in Stony Stratford, though when George proudly announced his tenancy of The Wharf Inn in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of March 2nd, he makes reference to a previous abode of Wolverton Station. This was the old name for the area around the railway works.

Unfortunately, the hopes expressed in his announcement of a successful business appear not to have materialised, as on November 30th the same year The Wharf Inn is again being advertised to let, with immediate possession, implying a precipitous departure. The notice carried in Croydon’s Weekly Standard goes on to describe the pub as, “incoming very moderate; rent low, one acre of land attached.” It also adds that, “the present tenant going to another business.” It is not readily apparent where George and his family went, though in 1865, the license of the Rising Sun pub in Stony Stratford was reported transferred to the widow of a George Atkins. This seems plausible, as his wife remarried in 1867.

The census of 1861 was conducted on April 7th, so the Atkins must have arrived in Great Linford very shortly after the birth of two-month-old Flora in Stony Stratford, though when George proudly announced his tenancy of The Wharf Inn in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of March 2nd, he makes reference to a previous abode of Wolverton Station. This was the old name for the area around the railway works.

Unfortunately, the hopes expressed in his announcement of a successful business appear not to have materialised, as on November 30th the same year The Wharf Inn is again being advertised to let, with immediate possession, implying a precipitous departure. The notice carried in Croydon’s Weekly Standard goes on to describe the pub as, “incoming very moderate; rent low, one acre of land attached.” It also adds that, “the present tenant going to another business.” It is not readily apparent where George and his family went, though in 1865, the license of the Rising Sun pub in Stony Stratford was reported transferred to the widow of a George Atkins. This seems plausible, as his wife remarried in 1867.

More comings and goings

In the February 22nd, 1862, edition of Croydon’s Weekly Standard, it was announced that the license of The Wharf Inn had been transferred from George Atkins to a George Grace. There seems to have been a constant churn of landlords during this period, as the Post Office directory of 1864 names John Clamp as the incumbent landlord, followed by the news in Kelly’s directory of 1869 that a Thomas Sutton had taken over.

Also in this same period, the Newport Pagnell Railway Company (who had purchased and closed the canal in 1867) put the entire Wharf, including the pub, up for sale by auction. An advertisement carried in the Bicester Herald of August 23rd, 1867, describes lot number three as, “All that Freehold Public House called “Linford Wharf Inn” with the stabling, buildings, large garden, and appurtenances, in the occupation of Messrs, Rogers & Co.”

It remains unclear if the sale was successful, but Rogers and Co were advertising the inn for let in Croydon's Weekly Standard of February 19th, 1870, with applicants invited to apply to the brewery in Newport Pagnell.

Also in this same period, the Newport Pagnell Railway Company (who had purchased and closed the canal in 1867) put the entire Wharf, including the pub, up for sale by auction. An advertisement carried in the Bicester Herald of August 23rd, 1867, describes lot number three as, “All that Freehold Public House called “Linford Wharf Inn” with the stabling, buildings, large garden, and appurtenances, in the occupation of Messrs, Rogers & Co.”

It remains unclear if the sale was successful, but Rogers and Co were advertising the inn for let in Croydon's Weekly Standard of February 19th, 1870, with applicants invited to apply to the brewery in Newport Pagnell.

Samuel Elliott

The next decade did not get off to a great start, with Samuel Elliott of The Wharf Inn brought before the petty sessions to answer to a charge of, “allowing gaming in his house.” As reported in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News of December 31st, 1870, the game in question was called ninepins, and a plain clothes policeman named Henry Andrews had witnessed the landlord encouraging the participation of his customers. Elliott argued that he was unaware that it was a crime to allow games of chance in a pub (highly unlikely) and that besides they had been playing for beer, not money. This cut no ice with the magistrates, and he was fined £2, with 11 shillings, six pence costs.

Samuel can be found on the 1871 census, where we also learn that he is also plying a trade as a wheelwright; not the first landlord of a Great Linford pub to have a side-line. We also learn that he was 32 years of age and born in Milton in Northamptonshire. His wife Mary (nee Hobbs), also 32, was a native of Blisworth, and together they then had a family of five, the youngest Samuel, at five weeks old on the 1871 census (conducted on the evening of April 2nd) born at Great Linford.

Several reports carried in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News in August and September the same year seem to indicate that the previous year’s gambling conviction had come back to haunt Samuel, as the application to renew his license was running into opposition, and foolishly he had not presented himself in person to argue his case.

Though a clarifying newspaper account had yet to be discovered that would explain how he got out of this mess, the Elliotts undoubtedly held on to the license. The couple had another child at Great Linford, a daughter Mary in the third quarter of 1872, and a Return of Public and Beer Houses dated 29th September 1872 for the Northern and North Western Divisions of Buckinghamshire names Samuel as the publican. Their next child John was born at Stantonbury in the first quarter of 1875, so we can presume they left the village somewhere between the end of 1872 and early 1875.

Samuel can be found on the 1871 census, where we also learn that he is also plying a trade as a wheelwright; not the first landlord of a Great Linford pub to have a side-line. We also learn that he was 32 years of age and born in Milton in Northamptonshire. His wife Mary (nee Hobbs), also 32, was a native of Blisworth, and together they then had a family of five, the youngest Samuel, at five weeks old on the 1871 census (conducted on the evening of April 2nd) born at Great Linford.

Several reports carried in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News in August and September the same year seem to indicate that the previous year’s gambling conviction had come back to haunt Samuel, as the application to renew his license was running into opposition, and foolishly he had not presented himself in person to argue his case.

Though a clarifying newspaper account had yet to be discovered that would explain how he got out of this mess, the Elliotts undoubtedly held on to the license. The couple had another child at Great Linford, a daughter Mary in the third quarter of 1872, and a Return of Public and Beer Houses dated 29th September 1872 for the Northern and North Western Divisions of Buckinghamshire names Samuel as the publican. Their next child John was born at Stantonbury in the first quarter of 1875, so we can presume they left the village somewhere between the end of 1872 and early 1875.

Jane Bartholomew and a family business

The Bucks Herald of December 11th, 1875, reports the license has passed from an Issac Arnold to a Jane Bartholomew. This is the only record we have of Issac at The Wharf Inn, but the 1872 return of public and beer houses places a man of the same name at the parish of Bradwell (New) with Stantonbury, running what we can presume to be a humble beerhouse, as it had no sign.

After a period of rapid turnover of publicans, Jane Bartholomew at least holds onto The Wharf Inn for a few years, as she is listed in the Kelly’s trade directory of 1877. Jane’s maiden name was Kemp and she had been born in Great Linford in 1829; her great grandfather Thomas had been the landlord of The Black Horse Inn, but she had lived much of her life in Newport Pagnell with her blacksmith husband Henry Andrew Bartholomew.

Their son Harry Bartholomew would establish a photography business from Great Linford High Street in later years, but upon being widowed in 1871 Jane subsequently remarried in 1879, to a Great Linford resident named David Walters. As was always the case in these circumstances, marriage meant that the license transferred to the husband’s name, and it was from David that the license was subsequently transferred on December 1st, 1880, to a Christopher Kemp, Jane’s younger brother.

Though it clearly places Christopher at The Wharf Inn, the 1881 census (carried out on the evening of April 3rd) describes Christopher solely as a painter rather than a publican, and indeed this had been his previous trade, as is confirmed by the following account carried in Croydon's Weekly Standard of July 30th, 1881.

After a period of rapid turnover of publicans, Jane Bartholomew at least holds onto The Wharf Inn for a few years, as she is listed in the Kelly’s trade directory of 1877. Jane’s maiden name was Kemp and she had been born in Great Linford in 1829; her great grandfather Thomas had been the landlord of The Black Horse Inn, but she had lived much of her life in Newport Pagnell with her blacksmith husband Henry Andrew Bartholomew.

Their son Harry Bartholomew would establish a photography business from Great Linford High Street in later years, but upon being widowed in 1871 Jane subsequently remarried in 1879, to a Great Linford resident named David Walters. As was always the case in these circumstances, marriage meant that the license transferred to the husband’s name, and it was from David that the license was subsequently transferred on December 1st, 1880, to a Christopher Kemp, Jane’s younger brother.

Though it clearly places Christopher at The Wharf Inn, the 1881 census (carried out on the evening of April 3rd) describes Christopher solely as a painter rather than a publican, and indeed this had been his previous trade, as is confirmed by the following account carried in Croydon's Weekly Standard of July 30th, 1881.

Bean Feast – On Saturday last the painters working on the east side of the carriage works of the London and North-Western Railway held their annual outing when they took a very pleasant drive through Newport Pagnell, Broughton, and Fenny Stratford and returned to Linford, where they partook of a first-rate dinner, provided by host Kemp (late a fellow workman), of The Wharf Inn. A most pleasant evening was spent, and all returned home well pleased with their excursion.

This then not only confirms that Christopher was a painter at Wolverton Railway Works but had indeed become the landlord of The Wharf Inn, though on December 24th, 1881, he was advertising in Croydon’s Weekly Standard that the pub (with large garden attached) was available to let. However, it seems he had no takers. At a coroner’s inquest held on October 29th, 1882, at The Wharf Inn, Christopher is a witness concerning a suicide who had been recovered from the canal, and he identifies himself in his testimony as the landlord.

But he was certainly a jack of all trades, as Kelly's trade directory of 1893 describes his occupations as no less than, “Wharf Inn, wharfinger, canal carrier’s agent and painter.” Wharfinger is an archaic term for a person who runs a wharf, so Christopher appears to have been managing a business encompassing the entire Wharf at Great Linford; perhaps it was the burden of all these jobs that had led him to seek someone else to take over at the pub. Conceivably he was still feeling the pressure in 1883, as the pub was again being advertised to let (Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette, October 9th), but this time with applications invited to be sent to a firm called Allfrey and Lovell in Newport Pagnell.

We can identify Francis Allfrey on the 1881 census for Newport Pagnell as a “brewer employing 19 men”, and his presumed partner as William Lovell. It is clear from newspaper advertisements in this period that the Newport Pagnell Brewery (as it was often styled) managed a fairly large estate of public houses, so it seems that the Wharf Inn must have been one of those.

Though he is not mentioned in connection with the case, in October 1882, Christopher would have likely been witness to one of the periodic visits to his pub of the coroner, who frequently chose pubs as the location for inquests. Not it should be observed because of the salubrious surroundings and ready supply of beer, but because a pub was one of the largest public spaces available. It was also generally the case that the pub closest to a fatality was chosen. In this case, the inquest concerned a 32-year-old woman called Martha Paul Ratlidge, a resident of Great Linford, whom it was sadly concluded, had cast herself into the canal whilst in a state of "temporary insanity."

Christopher was still the landlord in June of 1883 as he is mentioned in connection with the arrangements for a fishing competition in the canal, but by 1887 the year’s Kelly’s trade directory lists him only as a Wharfinger and canal carriers agent. The meaning of canal carriers agent is uncertain, but one can presume he was acting as a go-between, arranging for the transit of goods on the canal. We know from a newspaper story reproduced later in this history that by 1890, he was styling himself the caretaker of the wharf.

There is an odd additional post-script to the story of the Kemps and their association with the Wharf and the selling of intoxicating drinks. The 1871 census lists Thomas and Sidney Kemp, the parents of Christopher Kemp, as running a “Beer House” at “Wharf Bridge.” It seems surprising that they would have been in such close proximity to The Wharf Inn, though as a Beer House they would have only been licensed to dispense beer; The Wharf Inn almost certainly was able to sell a wider range of alcoholic beverages. Thomas died in 1872, and we do not know if his widow continued in the trade, though she was lodging with her son by the time of the 1881 census.

But he was certainly a jack of all trades, as Kelly's trade directory of 1893 describes his occupations as no less than, “Wharf Inn, wharfinger, canal carrier’s agent and painter.” Wharfinger is an archaic term for a person who runs a wharf, so Christopher appears to have been managing a business encompassing the entire Wharf at Great Linford; perhaps it was the burden of all these jobs that had led him to seek someone else to take over at the pub. Conceivably he was still feeling the pressure in 1883, as the pub was again being advertised to let (Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette, October 9th), but this time with applications invited to be sent to a firm called Allfrey and Lovell in Newport Pagnell.

We can identify Francis Allfrey on the 1881 census for Newport Pagnell as a “brewer employing 19 men”, and his presumed partner as William Lovell. It is clear from newspaper advertisements in this period that the Newport Pagnell Brewery (as it was often styled) managed a fairly large estate of public houses, so it seems that the Wharf Inn must have been one of those.

Though he is not mentioned in connection with the case, in October 1882, Christopher would have likely been witness to one of the periodic visits to his pub of the coroner, who frequently chose pubs as the location for inquests. Not it should be observed because of the salubrious surroundings and ready supply of beer, but because a pub was one of the largest public spaces available. It was also generally the case that the pub closest to a fatality was chosen. In this case, the inquest concerned a 32-year-old woman called Martha Paul Ratlidge, a resident of Great Linford, whom it was sadly concluded, had cast herself into the canal whilst in a state of "temporary insanity."

Christopher was still the landlord in June of 1883 as he is mentioned in connection with the arrangements for a fishing competition in the canal, but by 1887 the year’s Kelly’s trade directory lists him only as a Wharfinger and canal carriers agent. The meaning of canal carriers agent is uncertain, but one can presume he was acting as a go-between, arranging for the transit of goods on the canal. We know from a newspaper story reproduced later in this history that by 1890, he was styling himself the caretaker of the wharf.

There is an odd additional post-script to the story of the Kemps and their association with the Wharf and the selling of intoxicating drinks. The 1871 census lists Thomas and Sidney Kemp, the parents of Christopher Kemp, as running a “Beer House” at “Wharf Bridge.” It seems surprising that they would have been in such close proximity to The Wharf Inn, though as a Beer House they would have only been licensed to dispense beer; The Wharf Inn almost certainly was able to sell a wider range of alcoholic beverages. Thomas died in 1872, and we do not know if his widow continued in the trade, though she was lodging with her son by the time of the 1881 census.

Charles Agutters Draper

The next person we know to have been publican of The Wharf Inn is Charles Agutters Draper, born 1856 in Poddington, Bedford. He had married Ellen Goddard at Elstow on October 12th, 1876, and they had at least eight children, four of whom were born at Great Linford between 1885 and 1890, most likely at The Wharf Inn.

We can place Charles and his family at The Wharf Inn in 1885 for all the wrong reasons, as it was reported in the Bucks Herald of May 16th, that he had been up before the petty sessions for “having a quart measure in possession nearly a quarter of a pint against the purchaser.” He was fined 10 shillings, plus a further nine shillings, six pence in costs, with seven days to be served in jail if he could not pay. Not an auspicious start, and it seems not an isolated incident of breaking the rules, as the North Bucks Times and County Observer of June 16th, 1887, reported that Charles had been caught by a policeman serving beer to two boatmen after hours. He was again fined, though as the story observes, it was a lenient amount of two shillings, six pence.

Lenient or not, the bench was minded to remember the case, and a few months later, when he was back before the bench requesting the renewal of his license, the matter was cast into doubt by the specter of his previous conviction. Luckily the bench was again lenient, and after some debate the licence was approved. He was however warned that should be come before the justices again, he would likely forfeit his license.

An alarming story was recounted in Croydon's Weekly Standard of September 13th,1890, concerning the near drowning of an unnamed son of the Draper’s, illustrating the dangers of life on the banks of the canal. Ellen Draper’s actions are however nothing short of heroic, as the story below attests.

We can place Charles and his family at The Wharf Inn in 1885 for all the wrong reasons, as it was reported in the Bucks Herald of May 16th, that he had been up before the petty sessions for “having a quart measure in possession nearly a quarter of a pint against the purchaser.” He was fined 10 shillings, plus a further nine shillings, six pence in costs, with seven days to be served in jail if he could not pay. Not an auspicious start, and it seems not an isolated incident of breaking the rules, as the North Bucks Times and County Observer of June 16th, 1887, reported that Charles had been caught by a policeman serving beer to two boatmen after hours. He was again fined, though as the story observes, it was a lenient amount of two shillings, six pence.

Lenient or not, the bench was minded to remember the case, and a few months later, when he was back before the bench requesting the renewal of his license, the matter was cast into doubt by the specter of his previous conviction. Luckily the bench was again lenient, and after some debate the licence was approved. He was however warned that should be come before the justices again, he would likely forfeit his license.

An alarming story was recounted in Croydon's Weekly Standard of September 13th,1890, concerning the near drowning of an unnamed son of the Draper’s, illustrating the dangers of life on the banks of the canal. Ellen Draper’s actions are however nothing short of heroic, as the story below attests.

GREAT LINFORD NARROW ESCAPE PROM DROWNING. On Thursday afternoon, September 4, a narrow escape front drowning occurred in this village, to Mrs. Draper, wife of the landlord of the Wharf Inn. The Inn stands facing the Grand Junction Canal, and some of Mrs. Draper's children were playing on the canal bank, when one of them fell into the water at a deep spot. The child's screams attracted the attention of its mother, who at once came out of the house fully dressed and plunged in the water after her child. She succeeded in landing the child, but was unable, owing to the weight of her clothes, to extricate herself, and falling back into the water was in imminent danger of losing her life. Mr. Christopher Kemp, who is caretaker at the wharf, hearing the commotion made the best of his way to the scene and with assistance the unfortunate woman was eventually got to the bank in safety, not, however, before she had lost consciousness. She was at once taken into the home and the usual restoratives were applied, and after some time she returned to consciousness, and is now progressing favourably towards recovery from the severe shock to the system. The child was soon restored, and is none the worse for its misadventure.

The Drapers were back in the papers in December of 1892, though for far from gallant reasons, Charles having been charged with an assault upon a John Wallis of Great Linford (he was bound over to keep the peace and fined £5.) Then in 1896 he was summonsed over a failure to pay the poor rate. These brushes with the law, neither of which involved breaches of the licensing rules, did not seem to impact his ability to run the pub, and it was not until November 1898 that it was reported in Croyden’s Weekly Standard that he was (voluntarily we presume) surrendering the license. Though he also worked as a carpenter, the 1901 census places the family in Elstow in Bedfordshire, (his wife’s home parish) where they were then occupying the Swan Inn.

Thomas and Sarah Lacey

In November 1898 the license was transferred from Charles Draper to William Boswell, proving another short tenure, as in April 1899 William relinquished the license to Thomas Lacey. In a break from the norm, the Lacey’s prove to be one of the longest serving families to live and work at The Wharf Inn. They are at The Wharf Inn on both the 1901 and 1911 census records, from which we can extract some details.

Thomas was born in Oldbury, Worcestershire in 1857. He had married a Sarah Stevens at Dudley on February 26th, 1875, and was a bargeman, plying a trade on the canals, so perhaps on his travels he came across an opportunity to put down some roots on dry land. By the time he and Sarah settled at The Wharf Inn, they had already had ten children together. On the day of the 1901 census, there were five of their children residing at The Wharf Inn, including one month old John.

There are few references to be found in the newspaper to the Lacey family, though an odd account concerning Sarah Lacey appears in the Wolverton Express of October 9th, 1908, pertaining to charges she had lodged against a travelling salesmen, whom she claimed had fraudulently obtained a photograph of her mother. The story as told to the court is a curious and indeed rather confusing one. The salesman in question, named Max Wolff, had visited the Wharf Inn, and offered to make an enlargement of the photograph, to which Sarah had agreed, on the apparent understanding that she might then purchase a frame. It appears that the enlargement was not forthcoming, and understandably, Sarah was keen to recover her mother’s photograph, which must have been precious to her. Questioned in court, Max Wolff, who it was observed, “spoke with a foreign accent”, agreed to the return of the photograph, but the court could not conclude if there had been any wrongdoing, though the magistrate observed that the defendant was “sailing very close to the wind” as he appeared to be misrepresenting himself.

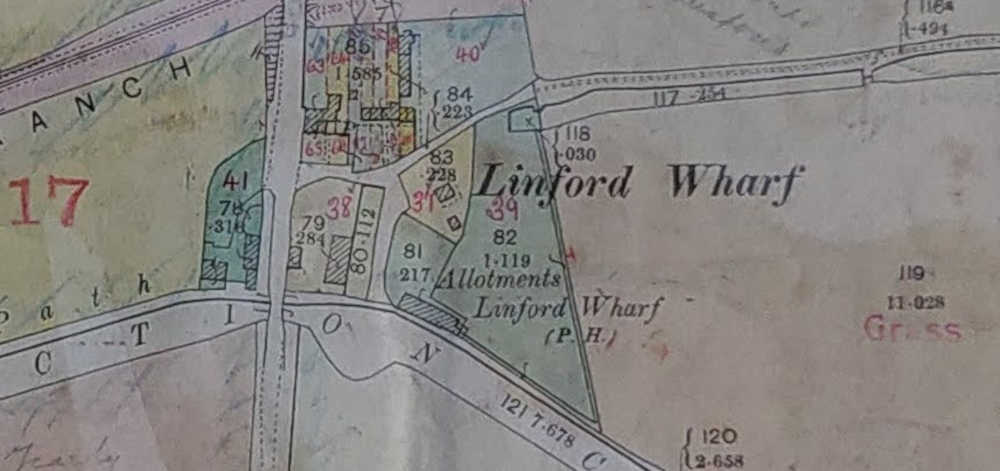

In 1910 a Valuation Office Survey map (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5.) was compiled of the parish, which like the 1840 tithe map, provides a detailed view of the buildings and land, with owners and occupiers named. From this we learn that The Wharf Inn with its garden (numbered 39 on the map) is as expected occupied by Thomas Lacey, but that the ownership has reverted to the Uthwatts. The land is estimated at one acre, with a gross annual value of £19 and a ratable value of £15 and ten shillings.

Thomas was born in Oldbury, Worcestershire in 1857. He had married a Sarah Stevens at Dudley on February 26th, 1875, and was a bargeman, plying a trade on the canals, so perhaps on his travels he came across an opportunity to put down some roots on dry land. By the time he and Sarah settled at The Wharf Inn, they had already had ten children together. On the day of the 1901 census, there were five of their children residing at The Wharf Inn, including one month old John.

There are few references to be found in the newspaper to the Lacey family, though an odd account concerning Sarah Lacey appears in the Wolverton Express of October 9th, 1908, pertaining to charges she had lodged against a travelling salesmen, whom she claimed had fraudulently obtained a photograph of her mother. The story as told to the court is a curious and indeed rather confusing one. The salesman in question, named Max Wolff, had visited the Wharf Inn, and offered to make an enlargement of the photograph, to which Sarah had agreed, on the apparent understanding that she might then purchase a frame. It appears that the enlargement was not forthcoming, and understandably, Sarah was keen to recover her mother’s photograph, which must have been precious to her. Questioned in court, Max Wolff, who it was observed, “spoke with a foreign accent”, agreed to the return of the photograph, but the court could not conclude if there had been any wrongdoing, though the magistrate observed that the defendant was “sailing very close to the wind” as he appeared to be misrepresenting himself.

In 1910 a Valuation Office Survey map (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5.) was compiled of the parish, which like the 1840 tithe map, provides a detailed view of the buildings and land, with owners and occupiers named. From this we learn that The Wharf Inn with its garden (numbered 39 on the map) is as expected occupied by Thomas Lacey, but that the ownership has reverted to the Uthwatts. The land is estimated at one acre, with a gross annual value of £19 and a ratable value of £15 and ten shillings.

Thomas requested extensions to drinking hours on occasion, once successfully in October 1910 for a fishing association dinner, then unsuccessfully for a football dinner in February 1911; the footballers may have been deemed a more riotous crowd. A rather curious note is to be found in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of April 22nd, 1911, to the effect that the sanatory committee had judged that a coat of whitewash applied to the walls might prevent or check disease (how this might help is uncertain), and that the owner would be so ordered.

Thomas passed away in 1913 in what can only be described as grim circumstances. On February 10th, 1913, he was admitted to Northampton Hospital suffering from fractured ribs on both sides of the chest, with injuries also to the lungs. In addition, the bones of his left forearm were fractured. The coroner’s inquiry held at Northampton on February 20th (his death in hospital seemingly dictating the venue for the inquest) heard from witnesses that Thomas had been observed leaving the sandpits near Great Linford with a horse and cart, but upon adjusting the reins and meaning to climb aboard, he was knocked down by a wheel, which then passed over his back and arm. He was attended by a doctor on the scene, but after his admission at Northampton hospital he had passed away from his injuries on the 19th.

A few other interesting details emerge from the newspaper report in the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of February 22nd. Though Thomas is described as a licensed victualler, it is clear that he is carting as a side-line, though in his testimony, his son indicated that he did not know Thomas was doing this. As it happens, this was not his only side-line, as it appears he was also finding work at the nearby brick kilns. Additionally, the horse and cart were owned by Philip Middleweek, landlord of the Black Horse Inn, but Thomas was engaged in work for the council, sub-contracted to an Edwin Sapwell. The article goes on to say that Thomas was not insured. The lack of responsibility for his death and the absence of health and safety concerns should not go unremarked upon.

Thomas left a legacy of £76 to his widow, who is listed as the landlady in the 1915 Kelly’s trade directory, meaning of course that she also had to take responsibility for any infractions of the rules, which in the period of the first world war included keeping lights from showing to prying eyes in the sky. So it was that she found herself summoned to the Newport Pagnell Divisional Petty Sessions on Wednesday, December 27th, 1916, accused of having shown a light on the evening of the 12th. She had been caught in the act by a Police constable Nicholls, wo said that he had seen a bright light shining from the window of the inn, and on entering the premises he found a double burner lamp alight on the table. Sarah wrote a letter of confession to the court, admitting that the lamp had been forgotten. A fine of five shillings was imposed.

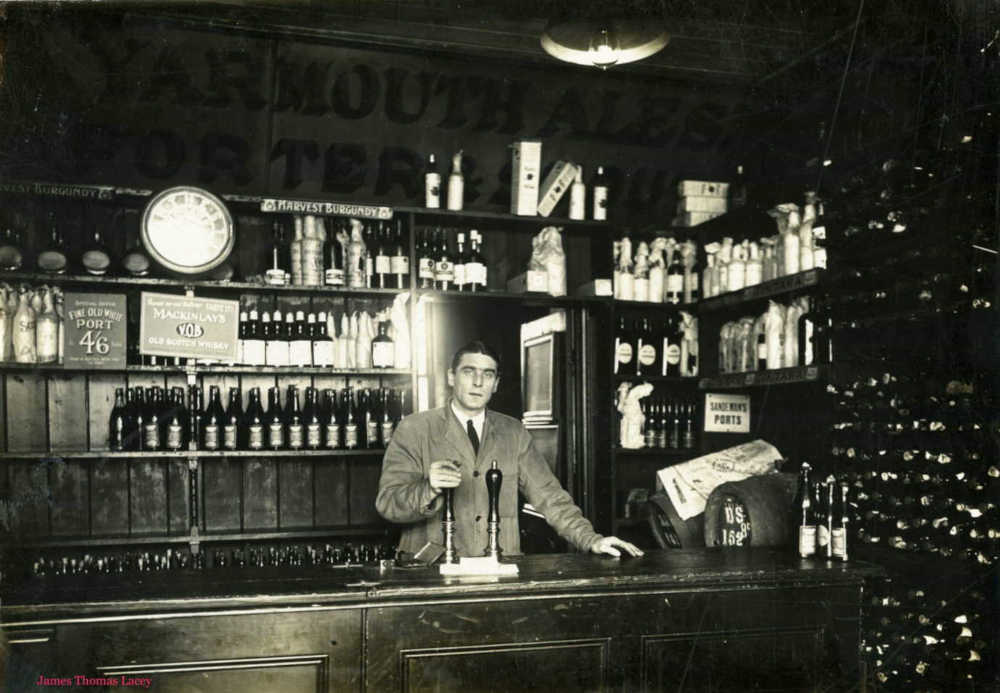

The electoral roll for 1918 lists Sarah as the only registered voter at The Wharf Inn, so presumably she was the landlady, but in 1919 the electoral roll names her son James Thomas Lacey (born 1892 in Fenny Stratford) as the occupant. James is categorically named the publican by the time of the 1921 census. With him in 1921 was his wife Florence Maud, nee Knight and three children, Russell, Cora and Mabel. Also present in the household on the day of the census was his brother John.

Thomas passed away in 1913 in what can only be described as grim circumstances. On February 10th, 1913, he was admitted to Northampton Hospital suffering from fractured ribs on both sides of the chest, with injuries also to the lungs. In addition, the bones of his left forearm were fractured. The coroner’s inquiry held at Northampton on February 20th (his death in hospital seemingly dictating the venue for the inquest) heard from witnesses that Thomas had been observed leaving the sandpits near Great Linford with a horse and cart, but upon adjusting the reins and meaning to climb aboard, he was knocked down by a wheel, which then passed over his back and arm. He was attended by a doctor on the scene, but after his admission at Northampton hospital he had passed away from his injuries on the 19th.

A few other interesting details emerge from the newspaper report in the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of February 22nd. Though Thomas is described as a licensed victualler, it is clear that he is carting as a side-line, though in his testimony, his son indicated that he did not know Thomas was doing this. As it happens, this was not his only side-line, as it appears he was also finding work at the nearby brick kilns. Additionally, the horse and cart were owned by Philip Middleweek, landlord of the Black Horse Inn, but Thomas was engaged in work for the council, sub-contracted to an Edwin Sapwell. The article goes on to say that Thomas was not insured. The lack of responsibility for his death and the absence of health and safety concerns should not go unremarked upon.

Thomas left a legacy of £76 to his widow, who is listed as the landlady in the 1915 Kelly’s trade directory, meaning of course that she also had to take responsibility for any infractions of the rules, which in the period of the first world war included keeping lights from showing to prying eyes in the sky. So it was that she found herself summoned to the Newport Pagnell Divisional Petty Sessions on Wednesday, December 27th, 1916, accused of having shown a light on the evening of the 12th. She had been caught in the act by a Police constable Nicholls, wo said that he had seen a bright light shining from the window of the inn, and on entering the premises he found a double burner lamp alight on the table. Sarah wrote a letter of confession to the court, admitting that the lamp had been forgotten. A fine of five shillings was imposed.

The electoral roll for 1918 lists Sarah as the only registered voter at The Wharf Inn, so presumably she was the landlady, but in 1919 the electoral roll names her son James Thomas Lacey (born 1892 in Fenny Stratford) as the occupant. James is categorically named the publican by the time of the 1921 census. With him in 1921 was his wife Florence Maud, nee Knight and three children, Russell, Cora and Mabel. Also present in the household on the day of the census was his brother John.

A muddle of landlords

Sarah Lacey was living at 16 Station Terrace with her son John when the 1923 electoral roll was compiled, the same year James gave up the license, but the departure of the Lacey family had wound up an impressive tenure at The Wharf Inn between them that lasted some 20 years. We now find on the 1923 electoral roll a Malcolm William Christie at The Wharf Inn, which presents something of a mystery, as the Wolverton Express of February 9th names the new landlord as an Alfred A. Christie, while the Kelly’s trade directory of 1924 names the landlord as Malcolm Alban Christie. Is this one and same person, with transcription errors to blame for the confusion, or is it an indication that there was more than one member of the Christie family involved in the running of the pub?

At present we cannot be sure, but the Wolverton Express of December 5th, 1924, noted that the license had been transferred to a Richard Ledger, on the grounds that Mr Christie was leaving due to ill-health. Further name confusion abounds, as the 1925 electoral roll names the registered voter at The Wharf Inn as a John Richard Ledger, alongside a Lily May Ledger, whom (presently lacking any corroborating evidence) we might presume to be his wife.

The Wolverton Express of September 24th, 1926, reported on the transfer of the licence from John Richard Ledger to a Cyril Leslie Pearce, but this was to be an even briefer tenure, as the Northampton Mercury of March 25th, 1927, had news that Cyril was relinquishing the license to a Lewis Oliver. Lewis at least puts down sufficient roots to register to vote, duly appearing on the 1927 electoral roll along with his wife Jessie. Lewis is also named as the landlord in the Kelly’s trade directory of 1928.

Unsurprisingly given the pace of turnover, we find an advert in the Wolverton Express of July 18th, 1930, that P. C. Gambell (an auctioneer) has been instructed by Mr L. Oliver to sell on Monday July 28th, “the household furniture and outside effects”, of The Wharf Inn. Further details are promised, and this is duly provided in an advertisement carried in the Wolverton Express of the 25th, which includes a long list of furniture and a considerable amount of equipment for the rearing of chickens. It seems that everything must go, even a pile of manure.

This was definitely the writing on the wall for Lewis, as the Wolverton Express of August 8th, 1930, announces that he has transferred the license to a John Joseph Foster; he is listed on the 1931 electoral roll with a Maud Foster, presumably his wife. But it is difficult to escape the feeling that The Wharf Inn is a poisoned chalice, as who do we find running an advert in the Wolverton Express scarcely a year later, but the aforementioned P. C. Gambell, whose services have now been secured by John Joseph Foster for the purposes of disposing of the contents of The Wharf Inn. The auction took place on August 31st, and included such items as a satin walnut bedstead, Windsor chairs, a gramophone and records and a B.S.A. motor cycle. Meanwhile, on the 21st of the month, the Wolverton Express had reported on the temporary transfer of the license to an Arthur Thomas Green.

At present we cannot be sure, but the Wolverton Express of December 5th, 1924, noted that the license had been transferred to a Richard Ledger, on the grounds that Mr Christie was leaving due to ill-health. Further name confusion abounds, as the 1925 electoral roll names the registered voter at The Wharf Inn as a John Richard Ledger, alongside a Lily May Ledger, whom (presently lacking any corroborating evidence) we might presume to be his wife.

The Wolverton Express of September 24th, 1926, reported on the transfer of the licence from John Richard Ledger to a Cyril Leslie Pearce, but this was to be an even briefer tenure, as the Northampton Mercury of March 25th, 1927, had news that Cyril was relinquishing the license to a Lewis Oliver. Lewis at least puts down sufficient roots to register to vote, duly appearing on the 1927 electoral roll along with his wife Jessie. Lewis is also named as the landlord in the Kelly’s trade directory of 1928.

Unsurprisingly given the pace of turnover, we find an advert in the Wolverton Express of July 18th, 1930, that P. C. Gambell (an auctioneer) has been instructed by Mr L. Oliver to sell on Monday July 28th, “the household furniture and outside effects”, of The Wharf Inn. Further details are promised, and this is duly provided in an advertisement carried in the Wolverton Express of the 25th, which includes a long list of furniture and a considerable amount of equipment for the rearing of chickens. It seems that everything must go, even a pile of manure.

This was definitely the writing on the wall for Lewis, as the Wolverton Express of August 8th, 1930, announces that he has transferred the license to a John Joseph Foster; he is listed on the 1931 electoral roll with a Maud Foster, presumably his wife. But it is difficult to escape the feeling that The Wharf Inn is a poisoned chalice, as who do we find running an advert in the Wolverton Express scarcely a year later, but the aforementioned P. C. Gambell, whose services have now been secured by John Joseph Foster for the purposes of disposing of the contents of The Wharf Inn. The auction took place on August 31st, and included such items as a satin walnut bedstead, Windsor chairs, a gramophone and records and a B.S.A. motor cycle. Meanwhile, on the 21st of the month, the Wolverton Express had reported on the temporary transfer of the license to an Arthur Thomas Green.

William Luck

Here we have something of a gap in the records, as little is to be found relating to The Wharf Inn in the 1930s, other than various petty crimes such as the theft of a bike from outside the inn in 1935, and several reports of coroner’s juries deliberating on more suicides in the canal, such as an inquest held in August 1936 into the death by drowning of a man named Theodore Lynham. However, at some as yet undetermined point in the 1930s, the pub had come into the hands of a William Luck, with reference made to him in the Wolverton Express of August 12th, 1938, pertaining to a fishing competition. William was putting up a ten-shilling prize for the heaviest fish, and judging for the competition was to take place in the pub.

Thanks to the 1939 Register, essentially an emergency census carried out on the eve of the Second World War, we can discover something about William Luck, that he was born on August 26th, 1896, and that his wife Ethel had been born on March 9th, 1900. There are two closed records due to privacy laws that may be children.

William is also listed as the landlord in the Kelly’s trade directory of 1939, but by November of 1940, the Wolverton Express named The Wharf Inn as one of seven pubs that had come up for transfer. Frustratingly, no names are offered, but we can presume that it was William Luck who was moving on, having found a new business at the Wine Vaults, in Newport Pagnell.

Thanks to the 1939 Register, essentially an emergency census carried out on the eve of the Second World War, we can discover something about William Luck, that he was born on August 26th, 1896, and that his wife Ethel had been born on March 9th, 1900. There are two closed records due to privacy laws that may be children.

William is also listed as the landlord in the Kelly’s trade directory of 1939, but by November of 1940, the Wolverton Express named The Wharf Inn as one of seven pubs that had come up for transfer. Frustratingly, no names are offered, but we can presume that it was William Luck who was moving on, having found a new business at the Wine Vaults, in Newport Pagnell.

Harold Hood, band leader

Information pertaining to the 1940s is frustratingly vague, but it appears that an A.V. Loe was installed as landlord on the application of the Aylesbury brewing company in the early 1940s, and it seems he was still there in early 1950, as he is named as the landlord in connection to the formation of a darts league for the North Bucks Licensed Victuallers Association.

The Wolverton Express of January 12th, 1951, carried the interesting news that the former publican, a Mr Robinson, had made way for a Mr Harold Hood, who is described as the leader of an “old time dance band.” It can come as no surprise then that musical entertainment would be on offer now at The Wharf Inn, with a “musical evening” advertised at the pub on January 21st, 1951, and another in February, but the curse of The Wharf Inn seems to have struck again, as by September Harold Hood is reported to have vacated the pub to make way for a Mr. Willis. Harold meanwhile took up the licence of the Forrester’s Arms in New Bradwell.

The Wolverton Express of January 12th, 1951, carried the interesting news that the former publican, a Mr Robinson, had made way for a Mr Harold Hood, who is described as the leader of an “old time dance band.” It can come as no surprise then that musical entertainment would be on offer now at The Wharf Inn, with a “musical evening” advertised at the pub on January 21st, 1951, and another in February, but the curse of The Wharf Inn seems to have struck again, as by September Harold Hood is reported to have vacated the pub to make way for a Mr. Willis. Harold meanwhile took up the licence of the Forrester’s Arms in New Bradwell.

The final years of The Wharf Inn

The Wolverton Express of October 1st, 1954, reported that a protection order had been approved by magistrates in favour of William McElroy. A protection order was a temporary transfer of the license before the usual petty sessions meeting could be held, and the holder of the license formally approved.

Toward the mid-1950s, the pub begins to be described on occasion as “The Old Wharf Inn”, which seems fair enough as it was getting on in years, and it was around this time that Ernest Johnson, formally of the Garibaldi Hotel in Northampton became the license. However, he passed away in 1957 aged 52. At this point, it seems likely that the last landlord of The Wharf Inn took up his position, a W. J. Brockwell, but we can name some other persons who lived at The Wharf Inn during this period, perhaps as live-in staff or lodgers.

An old Morris van in sound condition was up for sale from The Wharf Inn in August of 1956, with enquiries to be made to a person named Eldridge at the pub. A story carried in the Wolverton Express of December 20th, 1957, concerns ten-year-old Susan Mathis of The Wharf Inn, who had recently appeared at the Scale Theatre in London and the Hippodrome, Derby, performing a solo acrobatic dance routine. We also can be sure that in late 1958 a couple named Rundle were resident at the pub, as the Wolverton Express of January 2nd, 1959, reports upon the Christmas day delivery of a baby to Mrs Kathleen Rundle, to be named Tina.

The annual dinner of the Great Linford Hornets football team was held at The Wharf Inn on May 30th, 1958, with thanks conveyed to Mr Brockwell for providing changing rooms on the premises. He was certainly doing his best to keep the pub busy and profitable, but was not always successful. Under the headline “A dry do for caravanners”, the Wolverton Express of August 25th, 1961, reported that an application by the aforementioned W. J. Brockwell to serve drinks during a two-day caravan rally in the village had been denied by magistrates. He had better luck the following year, hosting the annual general meeting of the Great Linford Angling Association on April 18th, 1962, but in September of 1963 came the sad news of the impending end of The Wharf Inn.

The Wolverton Express carried a photograph of the pub, beneath the headline “Linford Wharf may close.” The accompanying article describes it as a, “picturesque public house and a favourite meeting place for canal folk, local people and Sunday evening strollers from nearby towns for very many years.” The landlord’s wife told the reporter that they were likely to leave within two weeks, and that her husband had already taken on the license for the Red Lion at Fenny Stratford. The sad news of the pubs demise was confirmed a week later, with a short follow-up story adding the fact that auctioneers had been appointed, and that no-one would be taking on the license. Happily at least, The Wharf Inn still survives today as a private residence.

Toward the mid-1950s, the pub begins to be described on occasion as “The Old Wharf Inn”, which seems fair enough as it was getting on in years, and it was around this time that Ernest Johnson, formally of the Garibaldi Hotel in Northampton became the license. However, he passed away in 1957 aged 52. At this point, it seems likely that the last landlord of The Wharf Inn took up his position, a W. J. Brockwell, but we can name some other persons who lived at The Wharf Inn during this period, perhaps as live-in staff or lodgers.

An old Morris van in sound condition was up for sale from The Wharf Inn in August of 1956, with enquiries to be made to a person named Eldridge at the pub. A story carried in the Wolverton Express of December 20th, 1957, concerns ten-year-old Susan Mathis of The Wharf Inn, who had recently appeared at the Scale Theatre in London and the Hippodrome, Derby, performing a solo acrobatic dance routine. We also can be sure that in late 1958 a couple named Rundle were resident at the pub, as the Wolverton Express of January 2nd, 1959, reports upon the Christmas day delivery of a baby to Mrs Kathleen Rundle, to be named Tina.

The annual dinner of the Great Linford Hornets football team was held at The Wharf Inn on May 30th, 1958, with thanks conveyed to Mr Brockwell for providing changing rooms on the premises. He was certainly doing his best to keep the pub busy and profitable, but was not always successful. Under the headline “A dry do for caravanners”, the Wolverton Express of August 25th, 1961, reported that an application by the aforementioned W. J. Brockwell to serve drinks during a two-day caravan rally in the village had been denied by magistrates. He had better luck the following year, hosting the annual general meeting of the Great Linford Angling Association on April 18th, 1962, but in September of 1963 came the sad news of the impending end of The Wharf Inn.

The Wolverton Express carried a photograph of the pub, beneath the headline “Linford Wharf may close.” The accompanying article describes it as a, “picturesque public house and a favourite meeting place for canal folk, local people and Sunday evening strollers from nearby towns for very many years.” The landlord’s wife told the reporter that they were likely to leave within two weeks, and that her husband had already taken on the license for the Red Lion at Fenny Stratford. The sad news of the pubs demise was confirmed a week later, with a short follow-up story adding the fact that auctioneers had been appointed, and that no-one would be taking on the license. Happily at least, The Wharf Inn still survives today as a private residence.