Prichard's Charity School

Built circa 1700 by Lord of the Manor Sir William Prichard (also spelt Pritchard) and endowed with a £10 a year charitable legacy to employ “an honest person to teach reading”, Great Linford’s original school house remains to this day a striking central feature of the Almshouse complex in the grounds of the present day Great Linford Manor Park; Sir Frank Markham in his History of Milton Keynes described it as, “a fine schoolroom and schoolmaster’s house with attractive paneling.” Alongside the £10 a year provided to employ a schoolmaster, Markham also states that parents later paid 1d a week for the provision of firewood.

£10 seems to have been the basic lower end rate for a teacher; Michael Reed in his A History of Buckinghamshire alludes to a range of salary between £10 and £26 for schools founded in the county during the 16th and 17th centuries, room and board included. Markham notes that a charity school in Wavendon was paying its teacher £40 a year in 1713, so this must have been a particular plumb appointment. It was also not uncommon for teachers to be allowed to take in paying borders to supplement their income, but though the Prichard fund was paying out at the low end of the scale, there is no evidence to suggest this occurred at Great Linford. An early indication of the number of pupils can be found in a book published in 1717 called, Methods used for erecting charity schools, which contains a list of schools throughout the country and the information that twenty boys were taught at Great Linford. Volume 21 of the Schools Inquiry Commission published in 1869 indicates the income of Prichard’s School was still then £10 and that 20 boys were enrolled, with the parents paying between 1d and 2d a week. Interestingly, the parents are described as, “labourers and railway workmen.”

Subjects taught

Though Prichard’s endowment had specified, “an honest person to teach reading”, it appears that from the earliest days of the school, the curriculum was somewhat broader. We know this thanks to a set of illuminating records from the early 1700s known as the Visitation Returns of Bishop William Wake. This was a survey the Bishop sent out to his clergy, asking a series of questions about conditions in their parishes. In the 1709 return, John Coles, the incumbent at the time, provides a surprising amount of detail, notably that the school, “teaches the poor children to read, write and cast account. They are taught the church catechism, and an abridgement of Bishopp (sic) William.”

To “cast account” or casting accounts, does not have an entirely clear definition, but to describe it as an attainment of basic numeracy would not be far off the mark; essentially then, the school was teaching what would come to be described as the three Rs. The word catechism is from ancient Greek and means to teach orally; in this context it is a summary or exposition of the Sacraments designed to be taught to children. Exactly what Bishop William had abridged is unclear, but one must assume it be a simplified religious tract suitable for children.

Jumping ahead to 1841, a Commissioners report into Charities, which summarised information gathered in 1833 labels Prichard’s school’s as “not classical”, and its goal to educate, “as many poor children as trustees should nominate, to be taught reading English.”

To “cast account” or casting accounts, does not have an entirely clear definition, but to describe it as an attainment of basic numeracy would not be far off the mark; essentially then, the school was teaching what would come to be described as the three Rs. The word catechism is from ancient Greek and means to teach orally; in this context it is a summary or exposition of the Sacraments designed to be taught to children. Exactly what Bishop William had abridged is unclear, but one must assume it be a simplified religious tract suitable for children.

Jumping ahead to 1841, a Commissioners report into Charities, which summarised information gathered in 1833 labels Prichard’s school’s as “not classical”, and its goal to educate, “as many poor children as trustees should nominate, to be taught reading English.”

The earliest schoolmasters

The Account Book of William Prichard's charity from December 1704-1761 (Buckinghamshire Archives PR_131/25/1), provides a wealth of information, including the names of the earliest teachers. On July 4th, 1707, John Marriot, schoolmaster, was paid £5 12 shillings in wages to Midsummer last. This will be a reference to the four quarters of the year (March 25th, Lady Day, June 24th, Midsummer Day, September 29th, Michaelmas Day and December 25th, Christmas Day), that were typically the time in the calendar appointed for the settling of accounts. Marriot was paid a further £5 on January 15th, 1708.

Marriot then may well have been the very first teacher employed by Prichard's school. The name appears in several other records including Bishop Webb’s Visitation of 1709; the charity account book records he was paid a further £5 in July of that same year. A man of this name from Great Linford also appears in a church subscription book of 1709, which records the names of ordained clergymen who had subscribed to the 39 Articles of Faith, the defining statements of the doctrines and practices of the Church of England, which had been codified after Henry VIII's Reformation. This is somewhat odd, as there is no clergyman of the name Marriot recorded at Great Linford and a John Marriot (surely our schoolmaster) who died at Great Linford circa 1713, left behind a will describing himself as a yeoman rather than a clergyman. However, it was certainly the case that teachers were required to be licensed by a Bishop, with the threat of a fine or imprisonment if caught teaching without one. Conceivably this might explain John's inclusion in the subscription book.

Marriot received a full year's salary of £10 on June 24th, 1710, but then his name disappears from the charity account book; it records only that a teacher was paid between the years 1710 and 1715, but does not specifically name him. Presumably, as noted above, Marriot had died in 1713, as that same year there is evidence for the appointment of a new master. At the Easter Quarter Session (courts) of April 16th, we find that a Thomas Hinton of Newton Longville, yeoman and “Inspector of the poor” was asked to show cause why he refused to grant a certificate to Thomas Barton, schoolmaster of Great Linford.

Thomas seems then to have been John’s successor, though what the certificate was and why it was refused requires further research. Clearly though the problem was resolved, as the charity account book entry for June 1717 names Thomas Burton as the master and records his payment of £10. The disparity between the Easter Quarter Session record which names the teacher as Barton and the charity account book, which names him as Burton, looks to be either a transcription error, or an original error by the recording clerk at the sessions; the charity account book names him Burton with consistency throughout his tenure.

There was a Thomas Burton married to an Elizabeth Spencer on November 18th 1716 at Great Linford, who may conceivably be the same person. Thomas continues to be recorded as the schoolmaster until 1741, thereafter the record becomes less specific, with no teacher named. The account book runs to 1761. There appears to be no record of a death for anyone of the name Thomas Burton (or variations of the name) in Great Linford, so until further account books can be examined, we are presented with a gap in the record.

Marriot then may well have been the very first teacher employed by Prichard's school. The name appears in several other records including Bishop Webb’s Visitation of 1709; the charity account book records he was paid a further £5 in July of that same year. A man of this name from Great Linford also appears in a church subscription book of 1709, which records the names of ordained clergymen who had subscribed to the 39 Articles of Faith, the defining statements of the doctrines and practices of the Church of England, which had been codified after Henry VIII's Reformation. This is somewhat odd, as there is no clergyman of the name Marriot recorded at Great Linford and a John Marriot (surely our schoolmaster) who died at Great Linford circa 1713, left behind a will describing himself as a yeoman rather than a clergyman. However, it was certainly the case that teachers were required to be licensed by a Bishop, with the threat of a fine or imprisonment if caught teaching without one. Conceivably this might explain John's inclusion in the subscription book.

Marriot received a full year's salary of £10 on June 24th, 1710, but then his name disappears from the charity account book; it records only that a teacher was paid between the years 1710 and 1715, but does not specifically name him. Presumably, as noted above, Marriot had died in 1713, as that same year there is evidence for the appointment of a new master. At the Easter Quarter Session (courts) of April 16th, we find that a Thomas Hinton of Newton Longville, yeoman and “Inspector of the poor” was asked to show cause why he refused to grant a certificate to Thomas Barton, schoolmaster of Great Linford.

Thomas seems then to have been John’s successor, though what the certificate was and why it was refused requires further research. Clearly though the problem was resolved, as the charity account book entry for June 1717 names Thomas Burton as the master and records his payment of £10. The disparity between the Easter Quarter Session record which names the teacher as Barton and the charity account book, which names him as Burton, looks to be either a transcription error, or an original error by the recording clerk at the sessions; the charity account book names him Burton with consistency throughout his tenure.

There was a Thomas Burton married to an Elizabeth Spencer on November 18th 1716 at Great Linford, who may conceivably be the same person. Thomas continues to be recorded as the schoolmaster until 1741, thereafter the record becomes less specific, with no teacher named. The account book runs to 1761. There appears to be no record of a death for anyone of the name Thomas Burton (or variations of the name) in Great Linford, so until further account books can be examined, we are presented with a gap in the record.

Benjamin Pavyer

The next schoolmaster we can trace with some confidence is a local man named Benjamin Pavyer (a surname subject to endless vagaries of spelling such as Pavior, Pavyor and Paviour), who was christened March 31st 1773 at Great Linford, the son of a Thomas and Ann. Benjamin married a Mary Blunt at Ashton in Northamptonshire on December 10th 1801 (the marriage records Benjamin as a resident of Great Linford) and they had at least three children together, Mary Ann in 1803, Thomas in 1805 and William in 1807.

Though some caution is warranted in making the connection, we know that a Benjamin Pavyer was for a time the resident farmer of Church Farm on the High Street, an indenture document of 1808 (Buckinghamshire Archives DX-2228) providing clear evidence to this effect. Unfortunately, Benjamin appears to have been widowed, probably that same year, as a Mary Paviour is recorded in the burial records of St. Andrews, her interment taking place on January 18th. However, Benjamin wasted no time in finding himself a new wife, as on October 8th that year, we find him remarrying at Great Linford to an Elizabeth Knight. Baptism and burial records point toward the marriage resulting in several more children, Edward in 1813, Sarah in 1815 and John in 1816, though sadly Sarah and John died within days of each other in April of 1817. Presuming we are correctly equating these deaths to Benjamin's family, it was to be a terrible year for him, as the parish burial records record that on June 22nd, a Elizabeth Pavyer, aged 26, was laid to rest in St. Andrew's churchyard; this we can take to be his wife.

More bad luck followed. In 1829, Benjamin's farming career appears to have been curtailed, as he was forced to surrender the farm under a so-called distress for rent, which allowed the landlord to effectively seize his property and farm stock to recover unpaid rent. But he seems to have bounced back, as when next we encounter the name Benjamin Pavyer, it is on the 1841 census, where he is described as a schoolmaster. Alongside him is 35-year-old Mary Pavyer, likely his daughter by his first marriage noted previously, born circa 1803. Though there is a slight discrepancy to be noted in her presumed age, this can be explained by the practice of rounding up or down adult ages in increments of five for this census.

We know that Benjamin was still the schoolmaster in 1847 as he is listed as such in the Pigot’s Trade Directory for that year, but unfortunately little else can presently be found about him, though we get a hint at his standing in the community from a lease dated 1818. In this document, he is named along with a Luke Alibone as, “yeoman, churchwardens and overseers”, pertaining to a, “small piece of land in Great Linford on which 4 cottages have been erected by the churchwardens and overseers of Great Linford adjoining the common street on the west." (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/117.)

Benjamin may not have been the sole teacher in this period, as the 1841 census for the village also mentions a Sabina Harris as a "schoolmistress". Unfortunately the 1841 census is extremely light on personal information, so other than her name, age (approximately 65) and profession, we know very little more of her. But we do know from the 1851 census that by this time she was no longer working as a teacher, and is instead listed as a pauper lacemaker, living at Canal Cottage adjacent to the Wharf. We also learn that she had been born in Deanshanger, Northamptonshire. It seems highly unlikely she had been commuting to work elsewhere as a teacher, so perhaps she did work alongside Benjamin, or perhaps as Benjamin entered his old age, he had hired Sabina as a substitute to undertake the day to day running of the school.

A Benjamin Paviour passed away at Great Linford toward the end of 1847 and though he does not appear in the parish burial records, it appears that he died in service, as we have a good anecdotal piece of evidence in the form of a letter written May 15th, 1848 by Great Linford resident Ann Capes (resident at Glebe House on the High Street.) In passing mention of Benjamin's replacement, she observes that, "They live in the house where Paryer (sic) lived and died." The letter is held by Northampton Record Office (L(MT)/57/1-2.) For more on Benjamin's career as a farmer, visit the page about Church Farm.

Though some caution is warranted in making the connection, we know that a Benjamin Pavyer was for a time the resident farmer of Church Farm on the High Street, an indenture document of 1808 (Buckinghamshire Archives DX-2228) providing clear evidence to this effect. Unfortunately, Benjamin appears to have been widowed, probably that same year, as a Mary Paviour is recorded in the burial records of St. Andrews, her interment taking place on January 18th. However, Benjamin wasted no time in finding himself a new wife, as on October 8th that year, we find him remarrying at Great Linford to an Elizabeth Knight. Baptism and burial records point toward the marriage resulting in several more children, Edward in 1813, Sarah in 1815 and John in 1816, though sadly Sarah and John died within days of each other in April of 1817. Presuming we are correctly equating these deaths to Benjamin's family, it was to be a terrible year for him, as the parish burial records record that on June 22nd, a Elizabeth Pavyer, aged 26, was laid to rest in St. Andrew's churchyard; this we can take to be his wife.

More bad luck followed. In 1829, Benjamin's farming career appears to have been curtailed, as he was forced to surrender the farm under a so-called distress for rent, which allowed the landlord to effectively seize his property and farm stock to recover unpaid rent. But he seems to have bounced back, as when next we encounter the name Benjamin Pavyer, it is on the 1841 census, where he is described as a schoolmaster. Alongside him is 35-year-old Mary Pavyer, likely his daughter by his first marriage noted previously, born circa 1803. Though there is a slight discrepancy to be noted in her presumed age, this can be explained by the practice of rounding up or down adult ages in increments of five for this census.

We know that Benjamin was still the schoolmaster in 1847 as he is listed as such in the Pigot’s Trade Directory for that year, but unfortunately little else can presently be found about him, though we get a hint at his standing in the community from a lease dated 1818. In this document, he is named along with a Luke Alibone as, “yeoman, churchwardens and overseers”, pertaining to a, “small piece of land in Great Linford on which 4 cottages have been erected by the churchwardens and overseers of Great Linford adjoining the common street on the west." (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/117.)

Benjamin may not have been the sole teacher in this period, as the 1841 census for the village also mentions a Sabina Harris as a "schoolmistress". Unfortunately the 1841 census is extremely light on personal information, so other than her name, age (approximately 65) and profession, we know very little more of her. But we do know from the 1851 census that by this time she was no longer working as a teacher, and is instead listed as a pauper lacemaker, living at Canal Cottage adjacent to the Wharf. We also learn that she had been born in Deanshanger, Northamptonshire. It seems highly unlikely she had been commuting to work elsewhere as a teacher, so perhaps she did work alongside Benjamin, or perhaps as Benjamin entered his old age, he had hired Sabina as a substitute to undertake the day to day running of the school.

A Benjamin Paviour passed away at Great Linford toward the end of 1847 and though he does not appear in the parish burial records, it appears that he died in service, as we have a good anecdotal piece of evidence in the form of a letter written May 15th, 1848 by Great Linford resident Ann Capes (resident at Glebe House on the High Street.) In passing mention of Benjamin's replacement, she observes that, "They live in the house where Paryer (sic) lived and died." The letter is held by Northampton Record Office (L(MT)/57/1-2.) For more on Benjamin's career as a farmer, visit the page about Church Farm.

William Burn

As noted, Ann Cape's letter also gives us the name of the new headmaster, Mr Burn, with the additional detail that he had brought his family with him to the newly repaired schoolhouse, the letter further revealing, "The Burns were in want of a home. They had been unsuccessful in their former school at Newport and their goods were sold off."

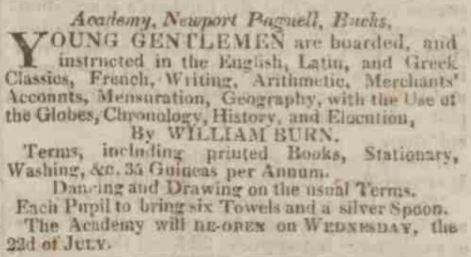

William Burn was born 1789 in the parish of Kingston, Hampshire. The earliest reference that can be found for him is a newspaper announcement in the Northampton Mercury of Saturday 11 July 1818, which reveals that he was the headmaster of The Newport Pagnell Academy. This would be a private fee-paying school, probably run from his home. The advert is intriguing, and while it is fairly certain that nothing like the same curriculum was followed at Great Linford, which one suspects must have been something of a step backward for William, it is worth reproducing here.

William Burn was born 1789 in the parish of Kingston, Hampshire. The earliest reference that can be found for him is a newspaper announcement in the Northampton Mercury of Saturday 11 July 1818, which reveals that he was the headmaster of The Newport Pagnell Academy. This would be a private fee-paying school, probably run from his home. The advert is intriguing, and while it is fairly certain that nothing like the same curriculum was followed at Great Linford, which one suspects must have been something of a step backward for William, it is worth reproducing here.

Bringing some towels seems a reasonable request, but why it would be a requirement to also bring a silver spoon is something of a mystery, though it was by no means an uncommon request, as other schools of the time set the same stipulation. The saying, “born with a silver spoon in their mouth” has no firmly acknowledged origin, so could this be where the phrase originated?

In 1822 William was charging students 35 guineas per year, though perhaps he had set his aspirations a little high, as just a year later he had dropped his fees to 25 guineas, still though a reasonable amount of money for the time. William continued to advertise sporadically until at least 1843, though his subsequent announcements appear to have been limited to term opening dates. But then in January of 1847 we find William in hot water, for here are published several ominous newspaper notices from an accountant at the Newport Pagnell Savings Bank, asking that creditors and debtors to William Burn, Schoolmaster, make themselves known. So, just as Ann Cape had written, William had gone bankrupt and indeed no further references to him in Newport Pagnell, nor his Academy, are evident. This then is how he came to be the schoolmaster of a small rural village in likely much reduced circumstances; remember the charity Prichard had established paid out only £10 per year for the employment of a teacher.

However, there is a hint that the original Prichard charity was no longer the sole source of income to the schoolmaster. In 1854, William’s daughter Elizabeth married a George Goff of the Newport Pagnell canal wharf, and in the newspaper announcement, William is described as the headmaster of a “National School”. This meant the Church of England was now involved in the running of the Almshouse School House.

The 1854 Trade Directory published by Musson & Craven provides an additional detail, stating that the school accommodates about 40 boys. William was still the school master at Great Linford by the time of the 1861 census, and joining him and his wife Ann was a lodger William G. Wilson and 13 year old George Wilson. George would subsequently publish a short memoir, which confirms that William Burn was his grandfather. George was a student from the age of seven, leaving Great Linford when he was between 15 and 16. His memoir provides a fascinating detail of the education offered, though it is not a flattering one. "I may say at once that the only thing I was conscious of learning while I was there was to say the whole of the Latin grammar by heart like a parrot, without the least idea of what it meant."

An additional account written by another student, and a close friend of George Wilson, provides further evidence that the schooling on offer at this time was of limited benefit, though in this case the blame is firmly attached to the students. Writing in his memoirs, Newman Thomas Cole recounts, "Like all boys we did not agree with being taught and, as there was no compulsion in attending, I am afraid we played truant very frequently." Newman also gives some additional insight into the state of the school, revealing that there were only about six pupils in attendance at the time, far short of the 40 suggested by the 1854 Musson & Craven trade directory. Additionally we learn that the headmaster was in the receipt of £20 a year for his services, and was allowed to retain the 2p a week the students paid. You can read Newman Thomas Cole's memoirs in full here.

William was still listed in the 1869 Kelly’s Trade Directory as the Schoolmaster, but was to depart at some point before 1871, as the census that year has him retired to the London household of his son William Wilson Burn, a manager of Praed’s Bank on Fleet Street. By this time, his grandson George Wilson whom we found at Great Linford in 1861 has become a student of medicine, and by 1901 had established himself as a surgeon in Brixton, so it seems that despite the manifest deficiency of his Latin lessons, his grandfather had instilled in him an instinct for learning; George’s obituary states he was also fluent in the artificial language Esperanto.

William Burn died at the Fleet Street home of his son on February 10th, 1872, aged 84. The notice of his death in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News of Saturday February 24th, 1872 makes reference to his residency at Great Linford and Newport Pagnell, but unfortunately offers no biography on his life. He was however quite likely one of the last persons to have undertaken teaching within the walls of the Almshouse school.

There were two “school mistresses” in the village in 1871, recorded on the census as Mezilla Wilson and Annie Mapley. Born in Banbury, Oxforshire, 24-year-old Mezilla was living at the “school house”, which must surely have been the Almshouse building, alongside a younger sister and brother, both of whom were listed as scholars. Annie was born in Great Linford and was 26 years old at the time of the census, the husband of an agricultural labourer named Charles. They lived on the High Street. Occupying the school house would seem to make Mezilla the senior of the two, presuming both were working together in Great Linford.

In 1822 William was charging students 35 guineas per year, though perhaps he had set his aspirations a little high, as just a year later he had dropped his fees to 25 guineas, still though a reasonable amount of money for the time. William continued to advertise sporadically until at least 1843, though his subsequent announcements appear to have been limited to term opening dates. But then in January of 1847 we find William in hot water, for here are published several ominous newspaper notices from an accountant at the Newport Pagnell Savings Bank, asking that creditors and debtors to William Burn, Schoolmaster, make themselves known. So, just as Ann Cape had written, William had gone bankrupt and indeed no further references to him in Newport Pagnell, nor his Academy, are evident. This then is how he came to be the schoolmaster of a small rural village in likely much reduced circumstances; remember the charity Prichard had established paid out only £10 per year for the employment of a teacher.

However, there is a hint that the original Prichard charity was no longer the sole source of income to the schoolmaster. In 1854, William’s daughter Elizabeth married a George Goff of the Newport Pagnell canal wharf, and in the newspaper announcement, William is described as the headmaster of a “National School”. This meant the Church of England was now involved in the running of the Almshouse School House.

The 1854 Trade Directory published by Musson & Craven provides an additional detail, stating that the school accommodates about 40 boys. William was still the school master at Great Linford by the time of the 1861 census, and joining him and his wife Ann was a lodger William G. Wilson and 13 year old George Wilson. George would subsequently publish a short memoir, which confirms that William Burn was his grandfather. George was a student from the age of seven, leaving Great Linford when he was between 15 and 16. His memoir provides a fascinating detail of the education offered, though it is not a flattering one. "I may say at once that the only thing I was conscious of learning while I was there was to say the whole of the Latin grammar by heart like a parrot, without the least idea of what it meant."

An additional account written by another student, and a close friend of George Wilson, provides further evidence that the schooling on offer at this time was of limited benefit, though in this case the blame is firmly attached to the students. Writing in his memoirs, Newman Thomas Cole recounts, "Like all boys we did not agree with being taught and, as there was no compulsion in attending, I am afraid we played truant very frequently." Newman also gives some additional insight into the state of the school, revealing that there were only about six pupils in attendance at the time, far short of the 40 suggested by the 1854 Musson & Craven trade directory. Additionally we learn that the headmaster was in the receipt of £20 a year for his services, and was allowed to retain the 2p a week the students paid. You can read Newman Thomas Cole's memoirs in full here.

William was still listed in the 1869 Kelly’s Trade Directory as the Schoolmaster, but was to depart at some point before 1871, as the census that year has him retired to the London household of his son William Wilson Burn, a manager of Praed’s Bank on Fleet Street. By this time, his grandson George Wilson whom we found at Great Linford in 1861 has become a student of medicine, and by 1901 had established himself as a surgeon in Brixton, so it seems that despite the manifest deficiency of his Latin lessons, his grandfather had instilled in him an instinct for learning; George’s obituary states he was also fluent in the artificial language Esperanto.

William Burn died at the Fleet Street home of his son on February 10th, 1872, aged 84. The notice of his death in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News of Saturday February 24th, 1872 makes reference to his residency at Great Linford and Newport Pagnell, but unfortunately offers no biography on his life. He was however quite likely one of the last persons to have undertaken teaching within the walls of the Almshouse school.

There were two “school mistresses” in the village in 1871, recorded on the census as Mezilla Wilson and Annie Mapley. Born in Banbury, Oxforshire, 24-year-old Mezilla was living at the “school house”, which must surely have been the Almshouse building, alongside a younger sister and brother, both of whom were listed as scholars. Annie was born in Great Linford and was 26 years old at the time of the census, the husband of an agricultural labourer named Charles. They lived on the High Street. Occupying the school house would seem to make Mezilla the senior of the two, presuming both were working together in Great Linford.

Final years and legacy

One would presume that the schoolhouse located at the Almshouses became effectively redundant as a place of learning with the opening in 1875 of the Church of England St Andrew’s school on the High Street, though the old school house continued to serve as a home for village headmasters for some time afterwards.

There are references in Trade Journals for 1877, 1883 and 1887 to indicate that Prichard’s charitable legacy of £10 per year was still being paid out for the purposes of reading and education, while a newspaper report in 1907 indicates the income was £20, providing for, “the letting of the teacher’s dwelling house, for the maintenance and improvement of the Great Linford Church School Buildings, and for the disposal of any residue of income in exhibitions, bursaries and prizes.”

This would seem to indicate that Prichard’s charity was now paying toward the upkeep of staff and facilities at St Andrew’s School, but for an intriguing advertisement placed by the Church Wardens of Great Linford in the Northampton Mercury of Friday September 15th, 1911. This calls for applications to the vacancy of School Master of the Church of England, to take care of the Charity School at a salary of £10 per annum, with a good and convenient house, rent free, with seven pounds allowed for the Sunday School. But St Andrew’s already had a school master of good standing, who did not leave his post until the 1920s, so does this advert imply that a “charity school” was still operating in parallel at Great Linford as late as 1911, and if so, where? This is a mystery yet to be solved.

The old school house had a number of other occupants unconnected to teaching; in 1960, Harry "Doggie" Robinson died while living there. He had for many years been a huntsman with the Bucks Otter Hunt. We know that by 1966 it was occupied by William Harold Massey and his wife Evelyn Kate. In 1939, William had been living in Little Linford, and was described on the census known as the England and Wales Register as a Cow-man and shepherd. This seems to suggest that the old school-house became general housing stock for the village in the 1960s.

This was not quite the end of the story, as the Almshouses received a new lease of life in the 1980s, serving for a time as artist's studios. Most recently they have largely lain empty, but in January of 2022, the Parks Trust entered into negotiations with Milton Keynes council to take over the buildings on a 999 year lease. Future plans include converting the old school house into a home which can be rented out, and for the Almshouses to be converted to a variety of uses, including an interpretation centre.

There are references in Trade Journals for 1877, 1883 and 1887 to indicate that Prichard’s charitable legacy of £10 per year was still being paid out for the purposes of reading and education, while a newspaper report in 1907 indicates the income was £20, providing for, “the letting of the teacher’s dwelling house, for the maintenance and improvement of the Great Linford Church School Buildings, and for the disposal of any residue of income in exhibitions, bursaries and prizes.”

This would seem to indicate that Prichard’s charity was now paying toward the upkeep of staff and facilities at St Andrew’s School, but for an intriguing advertisement placed by the Church Wardens of Great Linford in the Northampton Mercury of Friday September 15th, 1911. This calls for applications to the vacancy of School Master of the Church of England, to take care of the Charity School at a salary of £10 per annum, with a good and convenient house, rent free, with seven pounds allowed for the Sunday School. But St Andrew’s already had a school master of good standing, who did not leave his post until the 1920s, so does this advert imply that a “charity school” was still operating in parallel at Great Linford as late as 1911, and if so, where? This is a mystery yet to be solved.

The old school house had a number of other occupants unconnected to teaching; in 1960, Harry "Doggie" Robinson died while living there. He had for many years been a huntsman with the Bucks Otter Hunt. We know that by 1966 it was occupied by William Harold Massey and his wife Evelyn Kate. In 1939, William had been living in Little Linford, and was described on the census known as the England and Wales Register as a Cow-man and shepherd. This seems to suggest that the old school-house became general housing stock for the village in the 1960s.

This was not quite the end of the story, as the Almshouses received a new lease of life in the 1980s, serving for a time as artist's studios. Most recently they have largely lain empty, but in January of 2022, the Parks Trust entered into negotiations with Milton Keynes council to take over the buildings on a 999 year lease. Future plans include converting the old school house into a home which can be rented out, and for the Almshouses to be converted to a variety of uses, including an interpretation centre.