The Bucks Otter Hunt at Great Linford

That otter hunting was a barbaric activity best consigned to the history books seems hard to argue against, but equally, it was clearly considered by many at the time as a perfectly harmless country escapade, and so utterly above reproach. That the hapless otter was at least afforded the chance to escape the baying hounds seems to have afforded those indulging in hunting a veneer of respectability; the otter had after all a “sporting chance” of escape, even if that meant a terrifying chase of many hours. Should the exhausted animal succeed in eluding its pursuers, then the appreciative hunters doffed their caps to the pluck and fortitude of their prey.

Equally, it is also of course easy to criticise from the comfort of a more enlightened time. No doubt the success and fame of the Bucks Otter Hunt would have been a matter of some local pride in the village, and the suggestion that it was cruel and unnecessary likely met with ridicule and even incomprehension.

Sadly, as long as people and animals continue to compete for the same food sources, so there will be conflict, and inevitably it is the animal that will fare the worst. One such flashpoint would have been so called stew ponds, used to house fish stocks for monasteries and communities, and presumably a magnet for roving otters. Perhaps it was the depredations of otters that prompted King Henry II to appoint in 1157 a Roger Follo as the “King’s Otterer.” Later, in 1422, Henry VI appointed William Melbourne as “Valet of his Otter-Hounds”, who in turn paid a huntsman tuppence a day to hunt with eight hounds. There is no direct evidence that Great Linford had a stew pond, though we might speculate that the round ornamental pond in the present-day manor park grounds was converted from an earlier pond that served this purpose.

For an idea of what an otter hunt may have looked like in those days, we can turn to The Master of the Game, written circa 1410 by Edward, second Duke of York, it is purported to be oldest known book on English hunting, and contains the image below of men and hounds pursuing and impaling an otter on cruel 3-pronged spears. These continued to be used for centuries afterward, and only fell out of favour in the late 1800s.

The founding of the Bucks Otter Hunt

Otter hunting as an organised "sport" was a relatively new innovation, with the Culmstock Otter Hunt founded in 1790 claiming to be first such organisation of its kind. Though the founding of the Buckinghamshire Otter Hunt is commonly associated with the name Uthwatt (and the pack was certainly kennelled within the grounds of the Uthwatt family estate at Great Linford) there is sufficient evidence to confirm that two other names should be included in the earliest history of the hunt. These are Herbert Nathanial Clode and Henry Hoare, the former of Great Linford and the latter of Wavendon House. Exactly how this partnership was formed is uncertain, as the story is rather vague and sporadically recorded, but the earliest evidence uncovered to date is a brief note carried in the North Bucks Times and County Observer of January 31st, 1891, that attributes the creation of the otter hunt solely to a Mr H. N. Clode of Great Linford.

The Clodes were a well-to-do farming family in Great Linford and given that blood sports were predominantly a pastime of the upper classes, forming an otter Hunt might well have been seen by the Clodes as a way to advance or further cement their standing in the social pecking order. Herbert Nathanial Clode was the then 29-year-old son of John Clode, whose father had arrived in the parish toward the end of the 1830s. The family had a wine and spirits import business in Windsor, and there is some suggestion they enjoyed royal patronage. Herbert was described as a Grazier in the 1891 census; his father is listed as the head of the household and a retired gentleman. The family were then living at Great Linford House, a substantial farmhouse since sadly lost to the village that was located on land now occupied by Church Farm Crescent.

A more substantive newspaper article carried in the Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette of June 16th, 1891, adds the name Henry Hoare to the story as a co-founder of the hunt along with Bertie Clode (clearly the aforementioned Herbert) and a Mr Uthwatt, the squire of Great Linford. This would have been William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921.)

Henry Hoare’s family had long been associated with Wavendon House, whose gardens incidentally had been designed by Richard Woods; speculatively considered a potential designer of the pleasure gardens of Great Linford Manor Park. Henry Hugh Arthur Hoare was born at Wavendon in 1866 and was resident at the Wavendon estate in 1891. He is described in the census of that year as a landowner, so very much an equal to his otter hunting partner William Uthwatt.

A number of accounts, including one found in The Victoria history of the county of Bedford (1904) provides the additional interesting detail that the pack had first been the property of Henry Hoare, who had already hunted with them for several seasons, but he appears to have had the dogs transferred to Great Linford, presumably from his Wavendon estate. It is unclear if money changed hands, but certainly in September of 1889, Henry was advertising the pack for sale in the Field Magazine.

This leaves a gap between 1889 and January 1891 when Herbert Clode first enters the picture, so perhaps attempts to sell were unsuccessful, which led to the eventual move of the pack to Great Linford. As to exactly how Herbert Clode fitted into the partnership, he was certainly moving in the right circles, as in 1891 we find Clodes and Uthwatts rubbing shoulders at an annual Conservative Association dinner in the village. Intriguingly, there is also some strong corroboration that Herbert was indeed the principal figure in the early days of the hunt, as none other than the Sporting Life (May 7th, 1891) names him as the hunt “master.” This is further confirmed by a hunt report in the Bucks Herald of May 30th that same year, when again “Mr Clode” is referred to as the “master” of the hunt.

This all seems fairly conclusive, though by April of 1892, “The Field” magazine is describing the hunt as “Mr Uthwatt’s pack”, and creating some confusion for the reader, there are two persons present at the hunt named “Mr Clode”, one a “Huntsman” and the other a “Whip”; our aforementioned Herbert presumably and a brother perhaps? Also present was Gerard Uthwatt (employed on the day as a “whip”) and Mr and Mrs Hoare.

Herbert was no longer residing in Great Linford by the time of the 1901 census, having relocated to Fenny Stratford. Here he is described as a Job Master, an old term for the keeper of a livery stable, this being essentially a premises where horses can be stabled for a fee. He did however continue to attend hunts, though it seems not in an official participating capacity, but rather as a follower, hence he is listed as merely attending a hunt in 1906 in Warkwickshire, with “Mr Uthwatt” as the “master.”

The Clodes were a well-to-do farming family in Great Linford and given that blood sports were predominantly a pastime of the upper classes, forming an otter Hunt might well have been seen by the Clodes as a way to advance or further cement their standing in the social pecking order. Herbert Nathanial Clode was the then 29-year-old son of John Clode, whose father had arrived in the parish toward the end of the 1830s. The family had a wine and spirits import business in Windsor, and there is some suggestion they enjoyed royal patronage. Herbert was described as a Grazier in the 1891 census; his father is listed as the head of the household and a retired gentleman. The family were then living at Great Linford House, a substantial farmhouse since sadly lost to the village that was located on land now occupied by Church Farm Crescent.

A more substantive newspaper article carried in the Leighton Buzzard Observer and Linslade Gazette of June 16th, 1891, adds the name Henry Hoare to the story as a co-founder of the hunt along with Bertie Clode (clearly the aforementioned Herbert) and a Mr Uthwatt, the squire of Great Linford. This would have been William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921.)

Henry Hoare’s family had long been associated with Wavendon House, whose gardens incidentally had been designed by Richard Woods; speculatively considered a potential designer of the pleasure gardens of Great Linford Manor Park. Henry Hugh Arthur Hoare was born at Wavendon in 1866 and was resident at the Wavendon estate in 1891. He is described in the census of that year as a landowner, so very much an equal to his otter hunting partner William Uthwatt.

A number of accounts, including one found in The Victoria history of the county of Bedford (1904) provides the additional interesting detail that the pack had first been the property of Henry Hoare, who had already hunted with them for several seasons, but he appears to have had the dogs transferred to Great Linford, presumably from his Wavendon estate. It is unclear if money changed hands, but certainly in September of 1889, Henry was advertising the pack for sale in the Field Magazine.

This leaves a gap between 1889 and January 1891 when Herbert Clode first enters the picture, so perhaps attempts to sell were unsuccessful, which led to the eventual move of the pack to Great Linford. As to exactly how Herbert Clode fitted into the partnership, he was certainly moving in the right circles, as in 1891 we find Clodes and Uthwatts rubbing shoulders at an annual Conservative Association dinner in the village. Intriguingly, there is also some strong corroboration that Herbert was indeed the principal figure in the early days of the hunt, as none other than the Sporting Life (May 7th, 1891) names him as the hunt “master.” This is further confirmed by a hunt report in the Bucks Herald of May 30th that same year, when again “Mr Clode” is referred to as the “master” of the hunt.

This all seems fairly conclusive, though by April of 1892, “The Field” magazine is describing the hunt as “Mr Uthwatt’s pack”, and creating some confusion for the reader, there are two persons present at the hunt named “Mr Clode”, one a “Huntsman” and the other a “Whip”; our aforementioned Herbert presumably and a brother perhaps? Also present was Gerard Uthwatt (employed on the day as a “whip”) and Mr and Mrs Hoare.

Herbert was no longer residing in Great Linford by the time of the 1901 census, having relocated to Fenny Stratford. Here he is described as a Job Master, an old term for the keeper of a livery stable, this being essentially a premises where horses can be stabled for a fee. He did however continue to attend hunts, though it seems not in an official participating capacity, but rather as a follower, hence he is listed as merely attending a hunt in 1906 in Warkwickshire, with “Mr Uthwatt” as the “master.”

Organisation and staff

The Bucks Otter Hunt required a considerable amount of administration and planning, with the master supported by a committee and paid staff. Amongst the known members of the committee was Sydney Biss of Tempsford, who served from circa 1936, retiring as Honorary Secretary in 1951.

The hunt was not just a weekend jaunt for a few dedicated individuals; in 1904 it was hunting on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, a situation broadly unchanged by 1936, when the annual report stated that the hounds had hunted on 63 days and would continue in the following season to hunt 3 days a week. Clearly this would have required a great deal of coordination to ensure that hunters and hounds had lodgings prearranged, and that hunt followers in the different counties visited were aware in good time that the otterhounds were abroad in their vicinity. To this latter end, regular advertisements were placed in newspapers giving notice of hunts and their start locations.

Followers paid an annual subscription to defray costs (£5 5 shillings in 1904), of which feeding the pack would have been one significant expense. Of incidental interest, it was reported in the Wolverton Express of January 22nd, 1960 that a Rowland “Roly” Richardson of number 3 Great Linford High Street had been a supplier of horse meat to the otter hunt for over 30 years. An anecdote from a former village resident also tells us that the huntsmen would collect dead animals to feed to the hounds.

It seems the costs of the running the hounds were not insignificant, even for a family with the resources of the Uthwatts, such that in the Stamford Mercury of March 1st, 1895, the committee makes it known that it wished, “to relieve the Master of some portion of the expenses, which are necessarily very heavy, being much increased with a pack of hounds travelling so wide a range of the country, and consequently compelled to be kennelled so frequently aware from home.” The article does not however articulate how this was to be achieved.

The Bucks Otter Hunt had their own distinct livery, recorded as follows in Otters and Otter Hunting by L. C. R. Cameron (1908): Red cap, blue coat, white waistcoat, blue breeches and stockings, red tie, gilt buttons engraved B.O.H. A copy of the year-end report for the Bucks Otter Hunt for 1953 includes a rule that only members authorised by the hunt master are allowed to wear the uniform. The same report indicates that those who pay a 5 shilling membership fee shall be entitled to wear the B.O.H button. A local resident recalls seeing the huntsman in his blue coat in the village. We also have the following account from the Birmingham Daily Post of September 24th, 1957, that adds the detail that both men and women wore the uniform. “The Buckinghamshire huntsmen and women. in their picturesque uniforms of blue coats, trousers or skirts, shoes and stockings, with red ties and caps. were led by the Master, Miss Stella Uthwatt.” Arthur Buck, a tailor living on Tickford Street in Newport Pagnell made the uniforms for many years until his retirement in 1955. You can read more about the staff of the Bucks Otter Hunt by clicking here.

The hunt was not just a weekend jaunt for a few dedicated individuals; in 1904 it was hunting on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, a situation broadly unchanged by 1936, when the annual report stated that the hounds had hunted on 63 days and would continue in the following season to hunt 3 days a week. Clearly this would have required a great deal of coordination to ensure that hunters and hounds had lodgings prearranged, and that hunt followers in the different counties visited were aware in good time that the otterhounds were abroad in their vicinity. To this latter end, regular advertisements were placed in newspapers giving notice of hunts and their start locations.

Followers paid an annual subscription to defray costs (£5 5 shillings in 1904), of which feeding the pack would have been one significant expense. Of incidental interest, it was reported in the Wolverton Express of January 22nd, 1960 that a Rowland “Roly” Richardson of number 3 Great Linford High Street had been a supplier of horse meat to the otter hunt for over 30 years. An anecdote from a former village resident also tells us that the huntsmen would collect dead animals to feed to the hounds.

It seems the costs of the running the hounds were not insignificant, even for a family with the resources of the Uthwatts, such that in the Stamford Mercury of March 1st, 1895, the committee makes it known that it wished, “to relieve the Master of some portion of the expenses, which are necessarily very heavy, being much increased with a pack of hounds travelling so wide a range of the country, and consequently compelled to be kennelled so frequently aware from home.” The article does not however articulate how this was to be achieved.

The Bucks Otter Hunt had their own distinct livery, recorded as follows in Otters and Otter Hunting by L. C. R. Cameron (1908): Red cap, blue coat, white waistcoat, blue breeches and stockings, red tie, gilt buttons engraved B.O.H. A copy of the year-end report for the Bucks Otter Hunt for 1953 includes a rule that only members authorised by the hunt master are allowed to wear the uniform. The same report indicates that those who pay a 5 shilling membership fee shall be entitled to wear the B.O.H button. A local resident recalls seeing the huntsman in his blue coat in the village. We also have the following account from the Birmingham Daily Post of September 24th, 1957, that adds the detail that both men and women wore the uniform. “The Buckinghamshire huntsmen and women. in their picturesque uniforms of blue coats, trousers or skirts, shoes and stockings, with red ties and caps. were led by the Master, Miss Stella Uthwatt.” Arthur Buck, a tailor living on Tickford Street in Newport Pagnell made the uniforms for many years until his retirement in 1955. You can read more about the staff of the Bucks Otter Hunt by clicking here.

The masters of the hunt

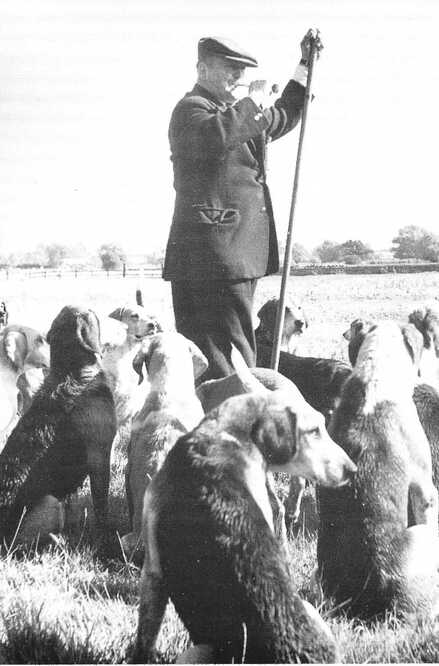

William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt with the Bucks otterhounds. Photo credit Ken Purkiss, reproduced from Vive la Chase.

William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt with the Bucks otterhounds. Photo credit Ken Purkiss, reproduced from Vive la Chase.

As previously established, it seems that the earliest master of the Bucks Otter Hunt was Bertram Clode, but he was swiftly replaced by a succession of masters drawn from the ranks of the Uthwatt family of Great Linford Manor. The first of these was William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt, born in 1870, though interestingly we find that in 1904, the post of honorary master was filled by John Powys, 5th Baron Lilford. By April of the same year, we find the hunt under the joint mastership of “Mr W and G Uthwatt”, presumably William and his brother Gerard, though at a hunt at Cropredy in Oxfordshire, it is Gerard who is named sole master. It seems then that the brothers were happily sharing joint responsibility for the hunt.

However, upon the death of William in 1921 there was a blip in the succession, with the plum role of master of the pack going temporarily to a James Arthur Jones. But why not an Uthwatt? To begin with, William’s two sons were otherwise occupied; William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt was serving with the Black Watch and Amyas Gerard John Andrewes Uthwatt was in India. As to his brother Gerard, logically he was the natural choice as he was already a prominent member of the hunt (and indeed as noted previously, was not unknown to act as master), but the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of October 29th reported (for reasons left unexplained) that he was unable to carry on the mastership. Perhaps he had gout, he was certainly reported suffering it in 1902.

The solution was to bring in James Arthur Jones, though it hardly strikes one as an ideal arrangement, as he was a resident not of Great Linford, but of Ombersley in Worcester. On the plus side, Jones had also led the Worchester Fox Hounds and the Northern Counties Otter Hunt, so undoubtedly he was eminently qualified. Equally he appears to have had plenty of time on his hands, since on the 1911 census he had recorded his profession as master of both fox and otter hounds. It is said he had the rather grim habit of adorning his car with a fox or otter “mask”, literally the head of an animal, according to the hunting season.

The arrangement that was made with Jones is not entirely clear, on the one hand the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of March 12th, 1922 stated that he had been “lent” the otterhounds, but later in the year the same newspaper (July 8th, 1922), described it implicitly as a “sale”. Notwithstanding any questions of ownership, Jones did lead the Bucks Otter Hunt that year, though there is a most curious statement in the August 4th, 1922, edition of the Hampshire Telegraph, to the effect that, “the Bucks Otter Hounds no longer exist.” However, reports of the hunt’s demise appear greatly exaggerated, as we continue to find reports in 1923 of the pack on the road under the continuing mastership of James Arthur Jones.

All told then, a rather turbulent year, but also an important one in the history of the Bucks Otter Hunt, as in March a memorial tablet was installed in St. Andrew’s church to the memory of William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt, adorned with the figure of an otter. The bishop of Buckingham dedicated the memorial in the presence of many notable sportsmen from the surrounding regions.

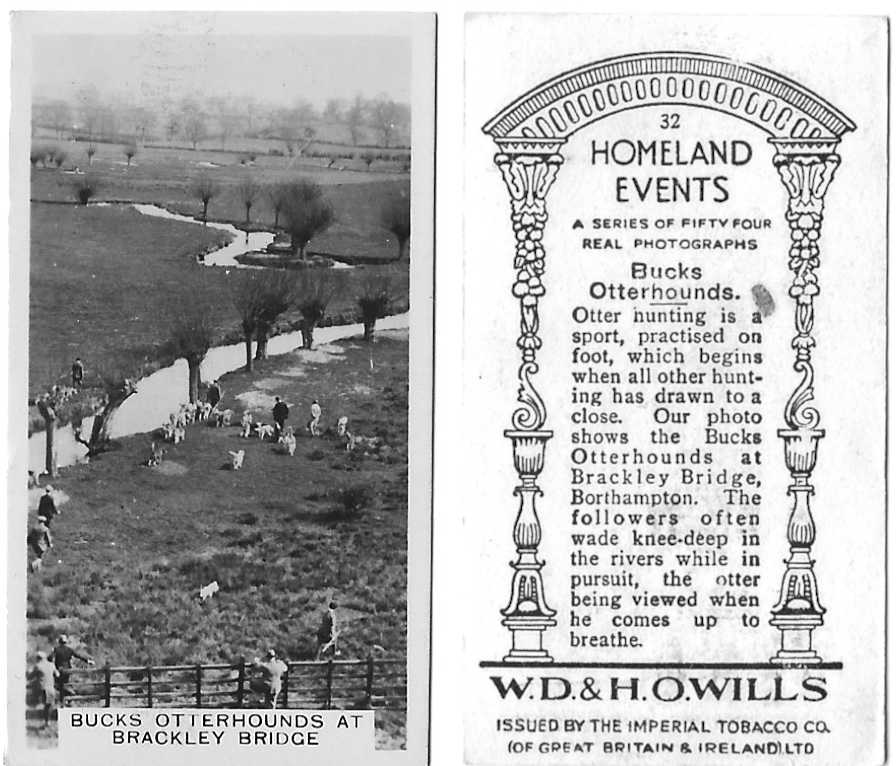

James Arthur Jones hunted with the Bucks Otter Hunt for only 2 seasons, as in 1924 William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt completed his army service with the Black Watch and returned to Great Linford. The hunt was so well known during his tenure that they even featured on a cigarette card issued in 1932.

However, upon the death of William in 1921 there was a blip in the succession, with the plum role of master of the pack going temporarily to a James Arthur Jones. But why not an Uthwatt? To begin with, William’s two sons were otherwise occupied; William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt was serving with the Black Watch and Amyas Gerard John Andrewes Uthwatt was in India. As to his brother Gerard, logically he was the natural choice as he was already a prominent member of the hunt (and indeed as noted previously, was not unknown to act as master), but the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of October 29th reported (for reasons left unexplained) that he was unable to carry on the mastership. Perhaps he had gout, he was certainly reported suffering it in 1902.

The solution was to bring in James Arthur Jones, though it hardly strikes one as an ideal arrangement, as he was a resident not of Great Linford, but of Ombersley in Worcester. On the plus side, Jones had also led the Worchester Fox Hounds and the Northern Counties Otter Hunt, so undoubtedly he was eminently qualified. Equally he appears to have had plenty of time on his hands, since on the 1911 census he had recorded his profession as master of both fox and otter hounds. It is said he had the rather grim habit of adorning his car with a fox or otter “mask”, literally the head of an animal, according to the hunting season.

The arrangement that was made with Jones is not entirely clear, on the one hand the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of March 12th, 1922 stated that he had been “lent” the otterhounds, but later in the year the same newspaper (July 8th, 1922), described it implicitly as a “sale”. Notwithstanding any questions of ownership, Jones did lead the Bucks Otter Hunt that year, though there is a most curious statement in the August 4th, 1922, edition of the Hampshire Telegraph, to the effect that, “the Bucks Otter Hounds no longer exist.” However, reports of the hunt’s demise appear greatly exaggerated, as we continue to find reports in 1923 of the pack on the road under the continuing mastership of James Arthur Jones.

All told then, a rather turbulent year, but also an important one in the history of the Bucks Otter Hunt, as in March a memorial tablet was installed in St. Andrew’s church to the memory of William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt, adorned with the figure of an otter. The bishop of Buckingham dedicated the memorial in the presence of many notable sportsmen from the surrounding regions.

James Arthur Jones hunted with the Bucks Otter Hunt for only 2 seasons, as in 1924 William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt completed his army service with the Black Watch and returned to Great Linford. The hunt was so well known during his tenure that they even featured on a cigarette card issued in 1932.

The importance to the family of the otter hunting is probably no better illustrated than in the photograph published on October 4th, 1934, on the front page of the Daily Mirror, of the marriage of William Uthwatt and Molly Adams. The bride and groom are pictured surrounded by the hounds and with an honour guard of hunt supporters and staff, holding aloft their otter-poles.

The Second World War seems to have impacted on otter hunting as it did most "sports", though writing in Hounds of Britain, (published 1973), Jack Ivester Lloyd offers that during the war years a "Peter How" (spelt Howe in other accounts), “was keeping going the nuclei of the North Bucks Beagles and the Bucks Otterhounds.” Howe appears to have been a local vet.

William Uthwatt passed away on December 14th, 1954, having continued as master for some 30 years. His will left the otterhounds to the hunt committee, “if they are willing to accept the bequest with a view to continuing to hunt the country which I and my family have hunted for half a century.”

Hunting appears to have gone entirely uninterrupted by the death of William as reporting of meets continues into 1955, and while we cannot precisely say how and when the decision was made, it is clear that Stella Uthwatt, the daughter of Gerard Uthwatt, had swiftly assumed mastership of the pack. She was mentioned in this capacity in The Times newspaper of July 4th, 1959, but after this it becomes less certain as to who was the master; newspaper reporting of hunts, which formally had been fulsome and detailed, dry up, and we have only the notifications presumably sent in by the hunt of meet dates and places. That she was still master in February 1960 is made clear, as she is described as such in accounts of the funeral for her kennelman Harry “Doggie” Robinson.

However, a story carried in the Stanford Mercury of the July 12th, 1963, suggests she may have stepped down by then. The story recounts the sad case of a hound which had become trapped in some willows and drowned, this despite the attempts of a Mr Uthwatt to effect a rescue, who having also got himself into difficulties had to be in turn rescued by another member of the hunt. The “Mr Uthwatt” in question was described as the master of the hunt, so we might presume this to be William Rupert Anthony Andrewes Uthwatt, who had inherited the manor in 1954.

Does this mean Stella had stepped aside and her position had been temporary? William was only 15 when he inherited, so perhaps he took over the Bucks Otter Hunt when he came of age? We do however find that by 1965, the Retford, Gainsborough & Worksop Times of August 6th was naming the joint master of the hunt as a Mrs P. C. E. Haswell of Ravensthorpe, Northamptonshire. Her inferred opposite number, an R. N. Saunders of Olney is named in the Birmingham Daily Post of August 10th, 1974, as joint master of the hunt, but at present no further useful information can be found on either person.

Stella Uthwatt moved away from Great Linford toward the end of her life, passing away at Crief in 1996. As a final postscript to her mastership of the Bucks Otter Hunt, Waddy Wadsworth (an authority on hunting) writing in Vive la Chase, devotes a page to lady masters of various hunts around the country. Oddly, though he is fulsome in his praise of a number of these lady masters, Stella is notable by her absence, an odd omission given Wadsworth’s own close connections to the Bucks Otter Hunt.

William Uthwatt passed away on December 14th, 1954, having continued as master for some 30 years. His will left the otterhounds to the hunt committee, “if they are willing to accept the bequest with a view to continuing to hunt the country which I and my family have hunted for half a century.”

Hunting appears to have gone entirely uninterrupted by the death of William as reporting of meets continues into 1955, and while we cannot precisely say how and when the decision was made, it is clear that Stella Uthwatt, the daughter of Gerard Uthwatt, had swiftly assumed mastership of the pack. She was mentioned in this capacity in The Times newspaper of July 4th, 1959, but after this it becomes less certain as to who was the master; newspaper reporting of hunts, which formally had been fulsome and detailed, dry up, and we have only the notifications presumably sent in by the hunt of meet dates and places. That she was still master in February 1960 is made clear, as she is described as such in accounts of the funeral for her kennelman Harry “Doggie” Robinson.

However, a story carried in the Stanford Mercury of the July 12th, 1963, suggests she may have stepped down by then. The story recounts the sad case of a hound which had become trapped in some willows and drowned, this despite the attempts of a Mr Uthwatt to effect a rescue, who having also got himself into difficulties had to be in turn rescued by another member of the hunt. The “Mr Uthwatt” in question was described as the master of the hunt, so we might presume this to be William Rupert Anthony Andrewes Uthwatt, who had inherited the manor in 1954.

Does this mean Stella had stepped aside and her position had been temporary? William was only 15 when he inherited, so perhaps he took over the Bucks Otter Hunt when he came of age? We do however find that by 1965, the Retford, Gainsborough & Worksop Times of August 6th was naming the joint master of the hunt as a Mrs P. C. E. Haswell of Ravensthorpe, Northamptonshire. Her inferred opposite number, an R. N. Saunders of Olney is named in the Birmingham Daily Post of August 10th, 1974, as joint master of the hunt, but at present no further useful information can be found on either person.

Stella Uthwatt moved away from Great Linford toward the end of her life, passing away at Crief in 1996. As a final postscript to her mastership of the Bucks Otter Hunt, Waddy Wadsworth (an authority on hunting) writing in Vive la Chase, devotes a page to lady masters of various hunts around the country. Oddly, though he is fulsome in his praise of a number of these lady masters, Stella is notable by her absence, an odd omission given Wadsworth’s own close connections to the Bucks Otter Hunt.

Followers of the hunt

In August of 1904, a stretch of river between Tempell Balsall and Knowle Hall in Solihull was hunted, accompanied by upwards of 50 ladies and gentlemen, including, “several well-known local sportsman.” Suffice to say, otter hunting was clearly a major social occasion, where those at the upper end of society could meet, mingle and make merry, with a visit to the pub later in the day.

The reports of meets are often something of a who’s who, with lords and ladies frequently amongst the followers. In 1897 we find the following amongst the attendees to a hunt at Maids Morton: Lord Addington and party, Lady Dashwood and the Hon. E. Douglas Pennant, M.P. (Master of the Grafton Hounds.) It feels very much like the modern concept of networking. The numbers were certainly often impressive, with upwards of 300 person reported at a hunt in Warwickshire in 1906.

Amongst the prominent local followers (and a committee member) of the hunt was the American born Major Charles Walter Mead, who had rented Great Linford Manor house circa 1911 to 1934 and had very much inserted himself into the life of a country squire. Another prominent local follower was Joseph Bailey, who was known as “Stunning Joe Bailey” for his immaculate turn-out at hunts. Born in 1816, he was described in his obituary (carried in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of January 30th, 1909) as one of the original members of the Bucks Otter Hunt. An old Etonian, he had also served as an officer in the Bucks Yeomanry.

One of the more morbid aspects of otter hunting was the practice of dividing up parts of the carcass of an otter, often to be given to followers. Hence we find a report in the Biggleswade Chronicle of September 17th, 1954, that the 4 pads (feet) of an otter were divided up between a Miss Carolyn Wilson, a Mr Michael Banks, a Stanley Gell and Mr. Albert Horner. The mask (head) and brush (tail) went to Sandye Place school. In June of 1961, as reported in the Louth Standard of the 16th, the mask was given to a Mr. Hyland.

Joseph Collinson, who had published in 1911 the first dedicated publication arguing against otter hunting, had this to say about the inclusivity of otter hunting and the dividing of the spoils, noting a, ‘deplorable feature of this sport is that its followers include all sorts and conditions of people: ministers of religion with their wives, young men and young women, sometimes even boys and girls’. Moreover, the intimacy of otter hunting meant that, ‘not only are they present at these infamous scenes, but, like the huntsmen, are worked up to the wildest pitch of excitement’ and moreover ‘join in the final worry and the performance of the obsequies, when the spoils of the chase are distributed’

The reports of meets are often something of a who’s who, with lords and ladies frequently amongst the followers. In 1897 we find the following amongst the attendees to a hunt at Maids Morton: Lord Addington and party, Lady Dashwood and the Hon. E. Douglas Pennant, M.P. (Master of the Grafton Hounds.) It feels very much like the modern concept of networking. The numbers were certainly often impressive, with upwards of 300 person reported at a hunt in Warwickshire in 1906.

Amongst the prominent local followers (and a committee member) of the hunt was the American born Major Charles Walter Mead, who had rented Great Linford Manor house circa 1911 to 1934 and had very much inserted himself into the life of a country squire. Another prominent local follower was Joseph Bailey, who was known as “Stunning Joe Bailey” for his immaculate turn-out at hunts. Born in 1816, he was described in his obituary (carried in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of January 30th, 1909) as one of the original members of the Bucks Otter Hunt. An old Etonian, he had also served as an officer in the Bucks Yeomanry.

One of the more morbid aspects of otter hunting was the practice of dividing up parts of the carcass of an otter, often to be given to followers. Hence we find a report in the Biggleswade Chronicle of September 17th, 1954, that the 4 pads (feet) of an otter were divided up between a Miss Carolyn Wilson, a Mr Michael Banks, a Stanley Gell and Mr. Albert Horner. The mask (head) and brush (tail) went to Sandye Place school. In June of 1961, as reported in the Louth Standard of the 16th, the mask was given to a Mr. Hyland.

Joseph Collinson, who had published in 1911 the first dedicated publication arguing against otter hunting, had this to say about the inclusivity of otter hunting and the dividing of the spoils, noting a, ‘deplorable feature of this sport is that its followers include all sorts and conditions of people: ministers of religion with their wives, young men and young women, sometimes even boys and girls’. Moreover, the intimacy of otter hunting meant that, ‘not only are they present at these infamous scenes, but, like the huntsmen, are worked up to the wildest pitch of excitement’ and moreover ‘join in the final worry and the performance of the obsequies, when the spoils of the chase are distributed’

A good day out

Accounts of Blood sports of all kinds were enthusiastically carried by the local papers and give a strong sense that the inherent barbarity of the “sport” is glossed over, romanticised or indeed entirely overlooked by the reporters, and one presumes much of the readership. The report of a hunt in Warkwickshire provides a good example of the tone of reporting and is reproduced in full below from the Rugby Advertiser of August 18th, 1906.

OTTER HOUNDS IN WARWICKSHIRE

A GOOD DAY ON THE LEAM.

A GOOD DAY ON THE LEAM.

In commencing their usual August visit to Warwickshire waters, the Bucks Otter Hounds spent an exciting afternoon on Tuesday on the Leam above Marton. Hounds were taken by train from Great Linford to Braunston, and there put into the river. The stream was narrow for several miles, and there was little water. and no drag was come upon until after the luncheon rest, for which a halt was made at the bridge at Kytes Hardwick. The state of the river improved towards Birdingbury, but it was not till they were within a mile of Marton village that hounds got on a good drag. There an otter was put down at a stretch of water with plenty of holts about it. An exciting half-hour followed, and there were evidently a couple of otters about, for while hounds had a good dreg upstream a hunter standing on midstream island tailed the quarry and had to hold it for a minute or more before the pack could be brought up. The otter was then handed to a huntsman, who took it on to the bank, but before hounds could lay hold the varmint escaped again into the water. So the hunt had to he resumed, and it was another half-hour before he was secured lower down stream. He was killed in midfield, and proved to be about 20Ibs in weight The drag higher up remained, and hounds were again put in, to work for another hour and a half, and to get more than one lead drag. The otter was ultimately secured in midstream, at a point overhung with trees, and while a crowd of hunters were in the water. Fine sport had now been going for nearly four hours, and hounds were whipped off. It was six o'clock before they were vanned. The day was one of the best of the season, or that has ever been had on Warwickshire rivers. Amongst those out were Mr Uthwatt (master), Mr and Mrs Gerard Uthwatt, Dr Frank Smith, Mr H Ratliff (Coventry). Mr J Foster (Solihull). Mr. Mrs, and Miss Dormer (Hill Wootton), the Misses Reynolds, Mr Willis (Leamington), Mr and Mrs Petch (Milverton), Colonel, Mrs, and Miss Burton, Mr and Miss Hewitt (Daventry), Mr. Simpson, Mrs F Giffard (Braunston). Mr Clode (Bletchley), Mr F W Nelson (Warwick). Mr W Riddell (Long Itchington), Mr and Mrs Storer, Mr F Fulwell, &c.

It is difficult to read an account like this, with its enthusiastic references to “fine sport” and the casual way in which a captured otter is offered up to the pack. This was one hunt on one day killing two otters, but the true scale of the cull by the Bucks Otter Hunt is apparent from a report published at the conclusion of the 1905 season, which provides a tally of 27 Otters killed, 7 in the Warwickshire district.

It should be noted that the Bucks Otter Hunt was also an organisation that could be called upon to eradicate otters that were judged to be competing with, or otherwise inconveniencing land-owners. A common complaint that brought the otter hunters out was damage to watercress beds. In cases like this, the object was generally not to hunt, but to simply eradicate an otter doing damage to the cress, which was caused not because otters ate the cress, but because they were partial to the small grubs that lived in the roots. These they would dig up with gusto.

Otters were considered by many as vermin that depleted valuable fish stocks, though on one occasion (reported in the Northants Evening Telegraph of May 14th, 1957) the Bucks Otter Hunt visited Cransley Hall after otters were accused of killing birds. After two hours hunting they failed however to even sight an otter, which perhaps brings into disrepute the original charges.

It should be noted that the Bucks Otter Hunt was also an organisation that could be called upon to eradicate otters that were judged to be competing with, or otherwise inconveniencing land-owners. A common complaint that brought the otter hunters out was damage to watercress beds. In cases like this, the object was generally not to hunt, but to simply eradicate an otter doing damage to the cress, which was caused not because otters ate the cress, but because they were partial to the small grubs that lived in the roots. These they would dig up with gusto.

Otters were considered by many as vermin that depleted valuable fish stocks, though on one occasion (reported in the Northants Evening Telegraph of May 14th, 1957) the Bucks Otter Hunt visited Cransley Hall after otters were accused of killing birds. After two hours hunting they failed however to even sight an otter, which perhaps brings into disrepute the original charges.

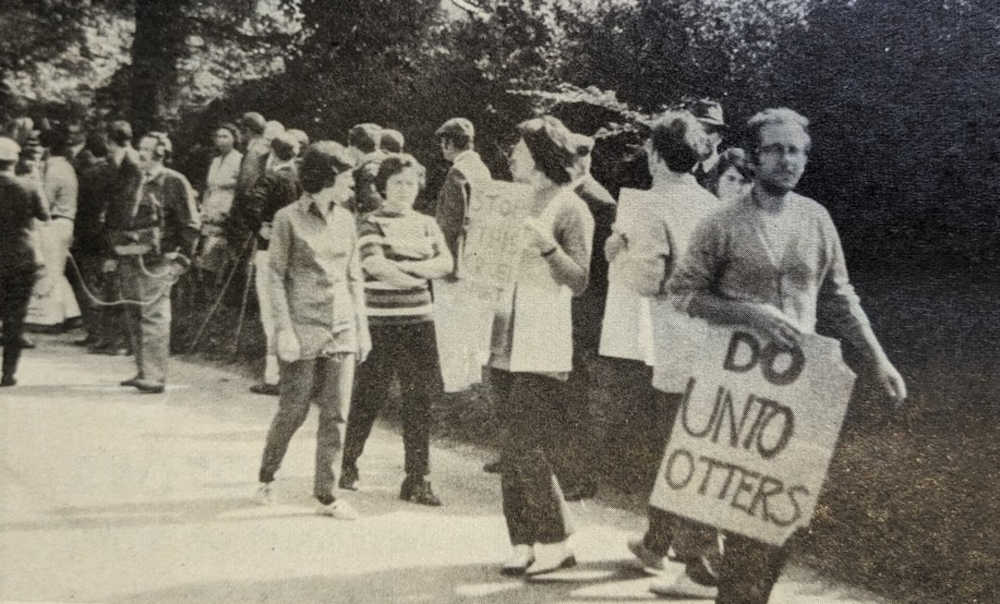

A dearth of otters and a growth in opposition

There has never been a shortage of people willing to protest against otter hunting and other blood-sports, but by the 1960s, what had started as a vocal minority was rapidly becoming a major thorn in the sides of the hunters. The battle lines had been drawn, and meets were regularly disrupted by hunt saboteurs. The Bucks Otter Hunt had been confronted as early as 1931, and while no evidence has yet been unearthed to show that they were regularly targeted in the years immediately afterward, it is clear that attitudes were hardening against the hunters, as least amongst town and city dwellers.

Perhaps the otter hunts could have kept going despite the growing clamour against them, but in the early 1960s it also became frighteningly evident that the otter population was suffering a dramatic decline. The hunters (backed up by post-mortems on dead otters) placed the blame primarily on organochlorine pesticides, but also on habitat loss and the invasive growth in the mink population; anything then but hunting. Though the otter hunters decided to suspend the killing of otters in the early 1960s, the pressure for a formal legal ban on the sport would however become overwhelming. For more on the history of opposition to the Bucks Otter Hunt, click here.

Perhaps the otter hunts could have kept going despite the growing clamour against them, but in the early 1960s it also became frighteningly evident that the otter population was suffering a dramatic decline. The hunters (backed up by post-mortems on dead otters) placed the blame primarily on organochlorine pesticides, but also on habitat loss and the invasive growth in the mink population; anything then but hunting. Though the otter hunters decided to suspend the killing of otters in the early 1960s, the pressure for a formal legal ban on the sport would however become overwhelming. For more on the history of opposition to the Bucks Otter Hunt, click here.

The end of the Bucks Otter Hunt

Exactly when the Bucks Otter Hunt were disbanded is uncertain. In what we might consider a sign of waning popularity or lack of funds, in 1966 it was announced that they were to merge with the Courtenay Tracy, a rather odd coming together of two geographically distant hunting organisations, as the Courtenay Tracy primarily hunted in Hampshire and Wiltshire. However, the merger seemed to be successful, at least in the short term, as in July of 1969, we find the newly named Bucks and Courtenay Tracy otterhounds hunting together at Stetton-on-Fosse in Warwickshire.

However, by 1970, the two seemed to have parted company, as the few newspaper accounts of hunts show the Bucks Otter Hunt and Courtenay Tracy operating independently again. Protesters were also continuing to make their voices heard, with a big turn out reported upon when the hunt were abroad at Castlethorpe on Saturday August 15th, 1970. Police were out in force, but things remained peaceable as the protesters trailed the hunt alongside the river, using smoke bombs, pepper, aerosol sprays and hunting horns to distract the hounds. Banners carried by the protesters contained slogans such as "Sadists in fancy dress" and "The otters haven't a dog's chance." The master of the hunt was identified as Richard Saunders of Lavendon, previously alluded to as a co-master of the hunt. He was dismissive of the protesters, though it was remarked upon by one observer that they were wasting their time anyway, as "the last otter caught near here was over ten years ago."

However, by 1970, the two seemed to have parted company, as the few newspaper accounts of hunts show the Bucks Otter Hunt and Courtenay Tracy operating independently again. Protesters were also continuing to make their voices heard, with a big turn out reported upon when the hunt were abroad at Castlethorpe on Saturday August 15th, 1970. Police were out in force, but things remained peaceable as the protesters trailed the hunt alongside the river, using smoke bombs, pepper, aerosol sprays and hunting horns to distract the hounds. Banners carried by the protesters contained slogans such as "Sadists in fancy dress" and "The otters haven't a dog's chance." The master of the hunt was identified as Richard Saunders of Lavendon, previously alluded to as a co-master of the hunt. He was dismissive of the protesters, though it was remarked upon by one observer that they were wasting their time anyway, as "the last otter caught near here was over ten years ago."

We know anecdotally that the otterhounds were expelled from their kennels at the Black Horse in 1972, but they must have found a new home, as the Birmingham Daily Post of August 10th, 1974, makes mention of them in connection to a report by the Mammal Society on the declining number of otters.

Thereafter however, the scent goes cold, except for a rather odd little postscript to the story from April of 1987, where two mourners, a Mr and Mrs Dick Sanders were listed at the funeral of a Mr Charles Frederick Burbidge of Collyweston in Northamptonshire; both representing the Bucks Otter Hunt. Waddy Wadsworth identifies a Dick Saunders from Snelson as a master of the Bucks otterhounds, but does not provide a date, only that he had succeeded William Uthwatt. That we have a reference to the otterhounds in 1987 is odd. Legally they could no longer hunt, so what this meant in practical terms is presently unknown.

Even though the sport was by then outlawed, there were some rumps of the otter hound tradition still then in existence. Indeed, the Courtney Tracy are still operating even today, having rebranded as a mink hunt, though even this avenue was cut off when mink hunting was itself made illegal in 2005. The Courtney Tracy now operates as a drag hunt under the watchful eye of hunt saboteurs. There is no evidence that the Bucks Otter Hunt ever shifted their attention to mink or drag hunting, so one can only conclude that the overwhelming pressure of declining otter numbers, legislation and public opinion saw the organisation fade away in the mid to late 1970s.

Thereafter however, the scent goes cold, except for a rather odd little postscript to the story from April of 1987, where two mourners, a Mr and Mrs Dick Sanders were listed at the funeral of a Mr Charles Frederick Burbidge of Collyweston in Northamptonshire; both representing the Bucks Otter Hunt. Waddy Wadsworth identifies a Dick Saunders from Snelson as a master of the Bucks otterhounds, but does not provide a date, only that he had succeeded William Uthwatt. That we have a reference to the otterhounds in 1987 is odd. Legally they could no longer hunt, so what this meant in practical terms is presently unknown.

Even though the sport was by then outlawed, there were some rumps of the otter hound tradition still then in existence. Indeed, the Courtney Tracy are still operating even today, having rebranded as a mink hunt, though even this avenue was cut off when mink hunting was itself made illegal in 2005. The Courtney Tracy now operates as a drag hunt under the watchful eye of hunt saboteurs. There is no evidence that the Bucks Otter Hunt ever shifted their attention to mink or drag hunting, so one can only conclude that the overwhelming pressure of declining otter numbers, legislation and public opinion saw the organisation fade away in the mid to late 1970s.