Linford Lodge (previously known as Ivy House and Elmhurst)

Located on Wood Lane close to The Green, we cannot be entirely certain what purpose Ivy House served when first constructed, but it was almost certainly a farmstead for some of its history and for a time at least had a small parcel of farmland associated with it. However, only a few of its independently wealthy occupants are known to have engaged in any kind of farming, and in later years it transitioned into a comfortable country home. It has also undergone a number of name changes in its history, from Ivy House to Elmhurst and finally Linford Lodge, when for a time it operated as a restaurant.

A brief entry in the book A Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes (1986, Paul Woodfield, Milton Keynes Development Corporation) describes the house as it was at the time, but it should be noted that a fire in 1919 caused significant damage, which is not acknowledged in the description, reproduced below.

Restaurant, formally a farmhouse, circa 18th century with some earlier work in the west wing. Limestone. Tiled roof. "L" plan with 3 bay elevation to road having a central door and slender Doric porch. Sash windows.

The fire of 1919 also affords us an additional detail about the house from a newspaper report, that it then had 14-16 rooms.

Thomas Bolding

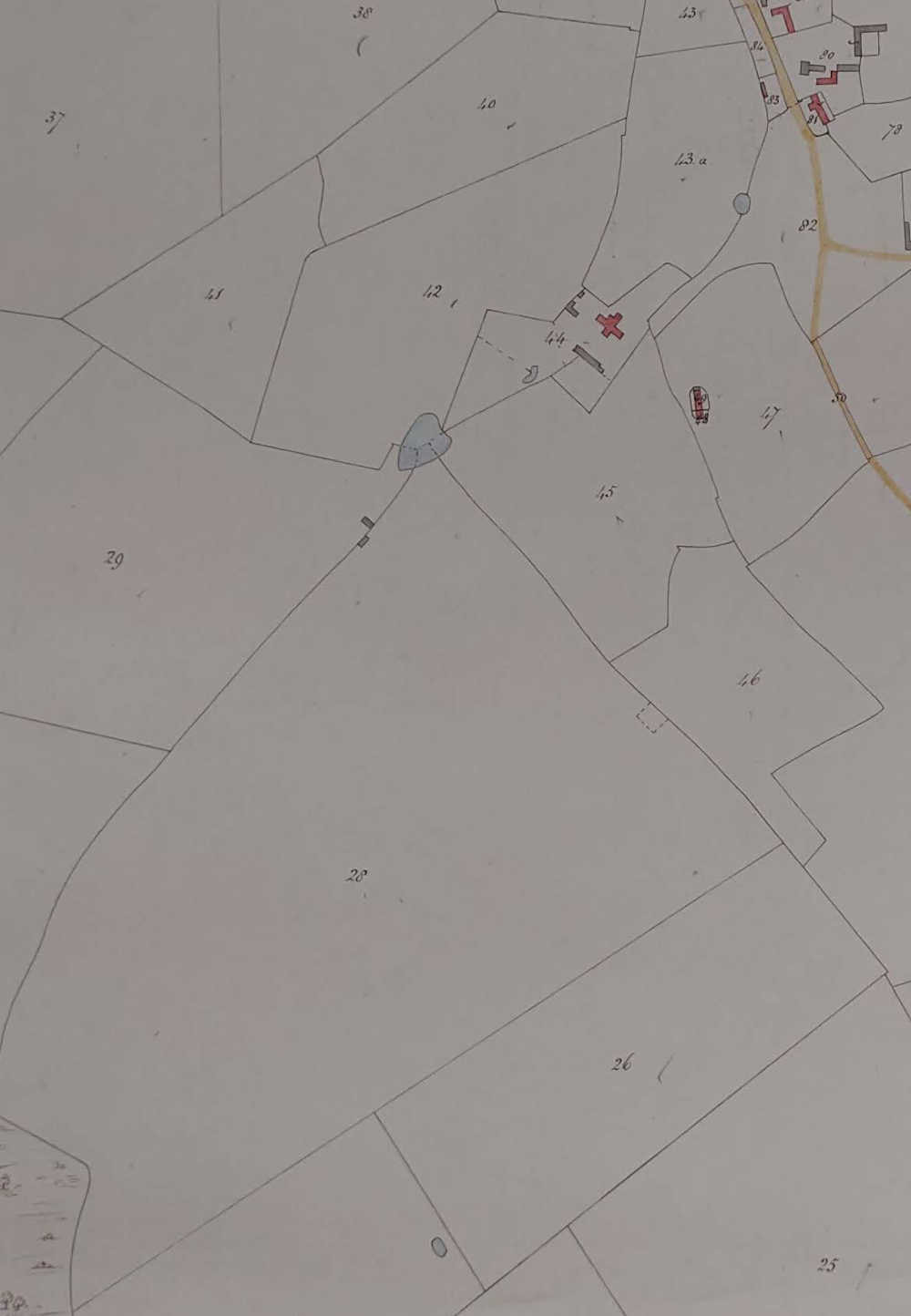

We can be sure of the occupant of Ivy House in 1840 (and for some years previously) as this was the year that a tithe map (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) was produced for the parish, which usefully includes depictions of houses along with a list of their owners and occupiers. With few exceptions, house names are not provided, but none-the-less, Ivy House is clearly identifiable, in the ownership of Henry Andrews Uthwatt esquire of Great Linford Manor and occupied by a Thomas Bolding. The house came with 57 acres of farmland, given over to grazing, and with a rateable value of £15. In addition to the "house and homestead", numbered 44 on the map (with the house coloured red and outbuildings in grey), we can also identify the five fields associated with the property: #26 (England Glade), #41 (Back Close), #43a (Turkey Lands), #45 (House Green) and #46 (Pignutts.)

We know that Thomas was present in the village at least as early as 1833, as the Buckinghamshire Archives hold a receipt dated April 7th (D-BAS/39/326/27) naming him as a resident of Great Linford and concerning £10 on account of the church at Great Woolstone. He was also granted a game certificate in 1836 and 1837 for Great Linford. He and his family are present on the 1841 census, but as this document is very thrifty with information it tells us only a few additional details, such that he was living on independent means; not surprising as he styled himself as an esquire, a rather flexible title implying that the bearer was a person of means and substance.

The origins of Thomas are rather obscure. He was born circa 1799, possibly to a John and Elizabeth Bolding. His wife was named Maria (or perhaps Anne Maria), but we are left struggling to identify her origins or a date and place for their marriage, and we can add only that the couple had three children, two of whom were baptised at nearby Haversham, an Anna Maria in 1825 and an Elizabeth in 1826. All are recorded at Great Linford on the 1841 census, except for a third daughter named Eleanor who may have been born in Broughton, Buckinghamshire in 1829. She is found living in London at the time with her uncles.

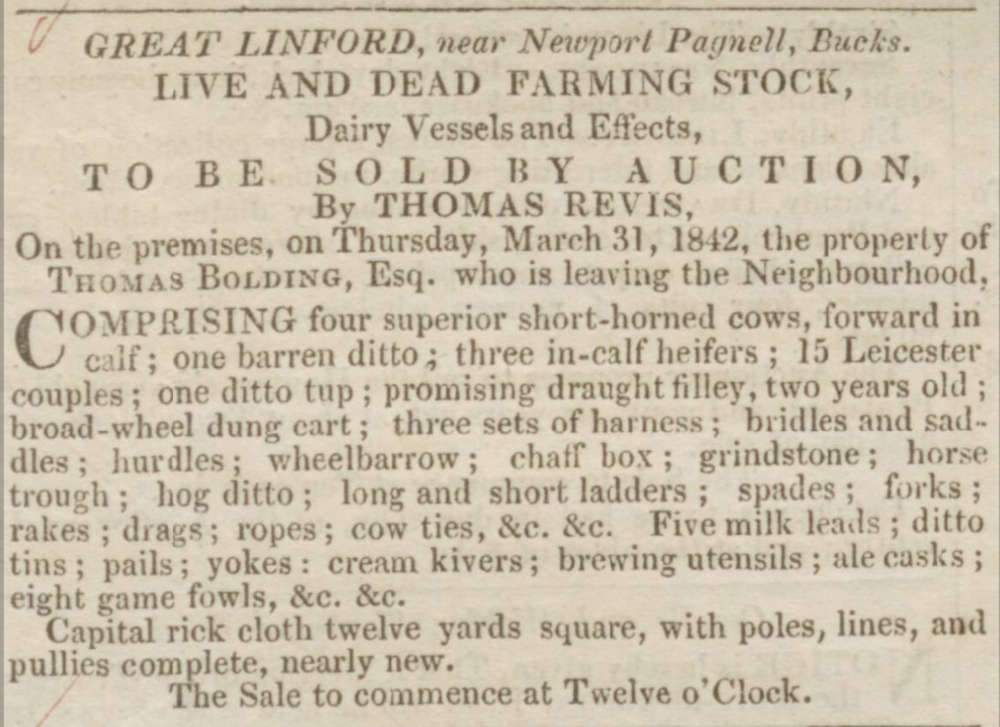

Thomas may have been what we could describe as a Gentleman Farmer, someone with sufficient money put aside or obtained from investments or inheritance to maintain a comfortable lifestyle and dabble in animal husbandry. He certainly maintained a herd of cattle, as in a notice published in the Northampton Mercury of March 26th, 1842, we learn that Thomas Bolding, Esquire, was leaving the neighbourhood, and selling his livestock and a substantial list of farming paraphernalia.

The origins of Thomas are rather obscure. He was born circa 1799, possibly to a John and Elizabeth Bolding. His wife was named Maria (or perhaps Anne Maria), but we are left struggling to identify her origins or a date and place for their marriage, and we can add only that the couple had three children, two of whom were baptised at nearby Haversham, an Anna Maria in 1825 and an Elizabeth in 1826. All are recorded at Great Linford on the 1841 census, except for a third daughter named Eleanor who may have been born in Broughton, Buckinghamshire in 1829. She is found living in London at the time with her uncles.

Thomas may have been what we could describe as a Gentleman Farmer, someone with sufficient money put aside or obtained from investments or inheritance to maintain a comfortable lifestyle and dabble in animal husbandry. He certainly maintained a herd of cattle, as in a notice published in the Northampton Mercury of March 26th, 1842, we learn that Thomas Bolding, Esquire, was leaving the neighbourhood, and selling his livestock and a substantial list of farming paraphernalia.

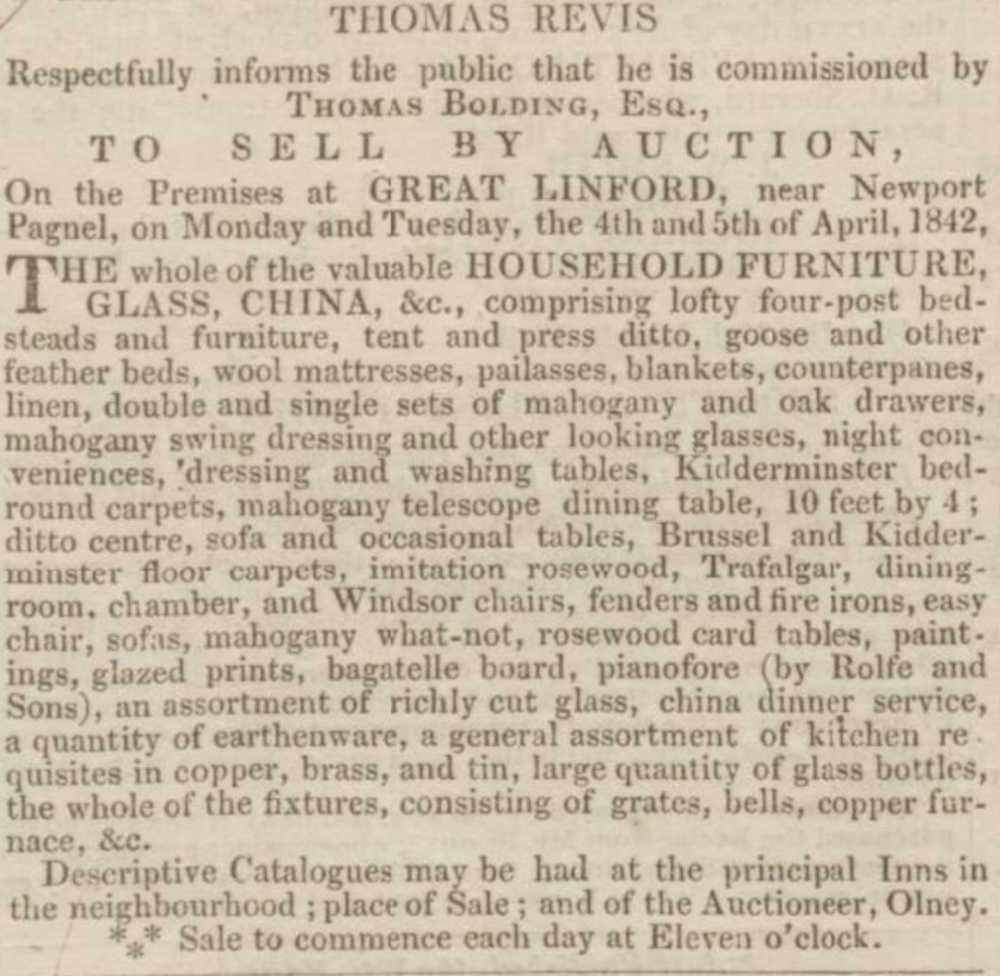

The same edition of the Northampton Mercury also carried a separate advertisement for the family's household goods, which certainly presents every appearance of very genteel living. It should be noted that sales of this nature were extremely common, and though it might seem to imply the family were short on funds, the likelihood is that relocating bulky household possessions over any distance would have been extremely costly and challenging, and so it was easier to sell up and buy anew.

As is typical of this period, these advertisements give not the slightest clue as to his address other than the property is in Great Linford, but this is hardly surprising when postal addresses (especially outside cities) seldom went much beyond a person’s name and their village or town. In close-knit communities where everyone knew everyone else, one imagines that a perspective buyer simply arrived in the village and enquired where they might find Mr Bolding’s property, to be told, “it be over yonder.”

As observed in several newspapers, Thomas passed away on July 12th, 1844, in Brighton. He was interred at St Nicholas Gardens, the graveyard of Brighton St. Nicholas church. His estate he left to his three daughters, to be equally divided between them, but though the will observes that he was “formally of Great Linford”, it does not specifically name any assets within the parish. That it also fails to mention his wife seems to imply that she had predeceased him. Thomas appointed his two brothers John and Henry as his executors, the latter a solicitor and the former a stockbroker, both working out of an office in a well-to-do area of St. John’s Wood in London. Why Thomas should have relocated to Brighton is unknown, perhaps he was in ill-health, and subscribed to the popular belief that sea-air would be restorative and invigorating.

As observed in several newspapers, Thomas passed away on July 12th, 1844, in Brighton. He was interred at St Nicholas Gardens, the graveyard of Brighton St. Nicholas church. His estate he left to his three daughters, to be equally divided between them, but though the will observes that he was “formally of Great Linford”, it does not specifically name any assets within the parish. That it also fails to mention his wife seems to imply that she had predeceased him. Thomas appointed his two brothers John and Henry as his executors, the latter a solicitor and the former a stockbroker, both working out of an office in a well-to-do area of St. John’s Wood in London. Why Thomas should have relocated to Brighton is unknown, perhaps he was in ill-health, and subscribed to the popular belief that sea-air would be restorative and invigorating.

Frederick Garratt

We cannot be sure who immediately succeeded Thomas Bolding, but the 1847 Kelly’s trade directory names a Frederick Garratt as a farmer in the parish, the same name then appearing in the 1851 census as residing at Ivy House, where he is described as a grazier, someone who reared cattle. Frederick, then 53 years of age, had been born in Bedford circa 1798; his mother was Ann, his father the splendid sounding Dingley Garratt, a name that could have come direct from the pages of a Dickens novel. Dingley’s profession was that of a whitesmith, which broadly speaking means he was probably a metalworker who did finishing work, such as lathing, burnishing or polishing. Equally, a whitesmith might also be someone who worked with “white” or light-coloured metals, or alternatively may have been a tinsmith.

We do not know if Thomas had ambition to follow in his father’s footsteps, certainly at least one sibling did, but information on his early life is very thin on the ground. It seems that he was resident in Bristol and Aldergate in London for a time, as on December 24th, 1824, he was married in Bristol, but declared his place of residence as Aldergate. His bride was Elizabeth Jarman and continuing the pattern of moving around, a daughter Eliza (seemingly their only child) was born at Bath in 1826.

The period between then and the family’s arrival in Great Linford circa 1847 is unfortunately a blank, but like Thomas Bolding before him, Frederick seems to have been living off personal wealth, though we can surmise he also what we might describe as a gentleman farmer. In the 1861 census question asking for his “Rank, profession or occupation” the answer is given as “fundholder”, with no mention of farming, but he had been described as a farmer in the 1853 Musson & Craven’s trade directory, and as a grazier in the Kelly’s directory of 1854.

Present in the Garratt household in 1861 are Frederick’s wife Elizabeth, their daughter Eliza, as well as Elizabeth’s sister Ann Jarman and a servant named Emma Haynes. The 1871 census is somewhat more expansive in regard to Frederick’s situation, and we are able to decipher that he had stock holdings but was also a farmer of 55 acres employing one labourer; 55 acres is as near as makes no difference to the 57 acres ascribed to the property in 1840. Frederick’s wife is not listed on the 1871 census as she had passed away on April 23rd, 1869, at the age of 70. She is buried in St. Andrew’s churchyard, as in due course would be her husband; their memorial can still be seen there.

Frustratingly, the enumerator’s entry for Frederick’s occupation on the 1881 census has been crossed out (perhaps by another official) and is illegible. Frederick was 83 at the time, and still living with his daughter, herself getting on in years at 50; we can imagine that she was perhaps acting as his carer and companion, though also in the household is 26-year-old Jane Smart, a housemaid from Lidlington in Bedfordshire.

1881 was the first year that the Ordnance Survey issued a 25 inch to mile map of the parish, on which we can clearly see Ivy House depicted, along with various outbuildings. Click here to view the 1881 O.S. map.

It does seem surprising that for all his long tenure at Ivy House, we find nothing at all in local newspapers concerning Frederick’s farming activities. Farmers are habitually busy people, and all manner of things can crop up that is deemed newsworthy: outbreaks of disease, the sale of crops, the winning of prizes and disputes of all kinds to name but a few, but Frederick seems to have lived a quiet unassuming life. He died on April 11th, 1887, and in keeping with his low profile, his death went largely unremarked upon by the press, though the occasion of his passing finally affords us a window into his life as a farmer.

On September 17th, 1887, an auctioneer placed a notice in Croydon's Weekly Standard newspaper announcing a sale to be held on the instructions of “Miss Garratt”, who was “relinquishing the occupation.” This reveals that the farm had 14 milch cows (meaning cows kept for milk) and heifers, as well as 69 Oxfordshire sheep and lambs. A rather small enterprise then, but to be expected given the limited extent of the land available for grazing.

We often find womenfolk continuing to run a farm’s affairs after the death of a husband or relative, but this was not to be for Frederick’s loyal daughter Eliza, despite her having steadfastly remained by his side for most of her life. Eliza is later to be found at Woburn Sands on the 1901 census, “living on her own means” and with a servant, so presumably at least not reduced to penury. She passed away at Woburn in 1905, aged 78.

We do not know if Thomas had ambition to follow in his father’s footsteps, certainly at least one sibling did, but information on his early life is very thin on the ground. It seems that he was resident in Bristol and Aldergate in London for a time, as on December 24th, 1824, he was married in Bristol, but declared his place of residence as Aldergate. His bride was Elizabeth Jarman and continuing the pattern of moving around, a daughter Eliza (seemingly their only child) was born at Bath in 1826.

The period between then and the family’s arrival in Great Linford circa 1847 is unfortunately a blank, but like Thomas Bolding before him, Frederick seems to have been living off personal wealth, though we can surmise he also what we might describe as a gentleman farmer. In the 1861 census question asking for his “Rank, profession or occupation” the answer is given as “fundholder”, with no mention of farming, but he had been described as a farmer in the 1853 Musson & Craven’s trade directory, and as a grazier in the Kelly’s directory of 1854.

Present in the Garratt household in 1861 are Frederick’s wife Elizabeth, their daughter Eliza, as well as Elizabeth’s sister Ann Jarman and a servant named Emma Haynes. The 1871 census is somewhat more expansive in regard to Frederick’s situation, and we are able to decipher that he had stock holdings but was also a farmer of 55 acres employing one labourer; 55 acres is as near as makes no difference to the 57 acres ascribed to the property in 1840. Frederick’s wife is not listed on the 1871 census as she had passed away on April 23rd, 1869, at the age of 70. She is buried in St. Andrew’s churchyard, as in due course would be her husband; their memorial can still be seen there.

Frustratingly, the enumerator’s entry for Frederick’s occupation on the 1881 census has been crossed out (perhaps by another official) and is illegible. Frederick was 83 at the time, and still living with his daughter, herself getting on in years at 50; we can imagine that she was perhaps acting as his carer and companion, though also in the household is 26-year-old Jane Smart, a housemaid from Lidlington in Bedfordshire.

1881 was the first year that the Ordnance Survey issued a 25 inch to mile map of the parish, on which we can clearly see Ivy House depicted, along with various outbuildings. Click here to view the 1881 O.S. map.

It does seem surprising that for all his long tenure at Ivy House, we find nothing at all in local newspapers concerning Frederick’s farming activities. Farmers are habitually busy people, and all manner of things can crop up that is deemed newsworthy: outbreaks of disease, the sale of crops, the winning of prizes and disputes of all kinds to name but a few, but Frederick seems to have lived a quiet unassuming life. He died on April 11th, 1887, and in keeping with his low profile, his death went largely unremarked upon by the press, though the occasion of his passing finally affords us a window into his life as a farmer.

On September 17th, 1887, an auctioneer placed a notice in Croydon's Weekly Standard newspaper announcing a sale to be held on the instructions of “Miss Garratt”, who was “relinquishing the occupation.” This reveals that the farm had 14 milch cows (meaning cows kept for milk) and heifers, as well as 69 Oxfordshire sheep and lambs. A rather small enterprise then, but to be expected given the limited extent of the land available for grazing.

We often find womenfolk continuing to run a farm’s affairs after the death of a husband or relative, but this was not to be for Frederick’s loyal daughter Eliza, despite her having steadfastly remained by his side for most of her life. Eliza is later to be found at Woburn Sands on the 1901 census, “living on her own means” and with a servant, so presumably at least not reduced to penury. She passed away at Woburn in 1905, aged 78.

William John Samuel

The next person we can identify at Ivy House is William John Samuel, who is found there on the 1891 census with his wife Alice and their four-year-old daughter Gwladys. William was born in Aberdare, Wales in 1857, but he and his family had arrived in Buckinghamshire by at least 1886, as Gwladys was born in Newport Pagnell that year. It seems highly likely then that Eliza Garratt made way for the Samuels, and perhaps William’s profession offers a clue as to why he was granted the tenure. William is described as a Land Agent and Surveyor, generally taken to mean that he was employed to look after the day to day running of an estate on behalf of the owner, including the collecting of rents. It does not seem then a great leap to imagine that his occupation of Ivy House came about because he was employed in this capacity by the Uthwatts.

Significantly, William is also listed at Ivy House in the 1891 Kelly’s trade directory, but not under the “commercial” heading, he is instead listed alongside the independently wealthy of the village, including the Lord of the Manor and the Rector; not then a mere tradesman. But the Uthwatts were still first among equals, and it is hard not to shake the suspicion that they had something to do with William’s subsequent relocation to “The Cottage”, located near to The Green on the High Street. William and his wife are to be found there on the 1901 census, though not necessarily an enormous sacrifice, as The Cottage could hardly be considered poor lodgings. William is also described as a land agent, and he and his wife remained there until at least 1907, when William’s name is last mentioned residing at Great Linford in a Kelly’s trade directory.

Significantly, William is also listed at Ivy House in the 1891 Kelly’s trade directory, but not under the “commercial” heading, he is instead listed alongside the independently wealthy of the village, including the Lord of the Manor and the Rector; not then a mere tradesman. But the Uthwatts were still first among equals, and it is hard not to shake the suspicion that they had something to do with William’s subsequent relocation to “The Cottage”, located near to The Green on the High Street. William and his wife are to be found there on the 1901 census, though not necessarily an enormous sacrifice, as The Cottage could hardly be considered poor lodgings. William is also described as a land agent, and he and his wife remained there until at least 1907, when William’s name is last mentioned residing at Great Linford in a Kelly’s trade directory.

Anna Maria Uthwatt and Gerard Uthwatt

As to Ivy House, the 1899 Kelly’s trade directory reveals that the new occupant is a Mrs Uthwatt, who we can identify as Anna Maria Uthwatt, nee Glascott, the widowed mother of the then Lord of the Manor, William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt. The 1901 census adds her younger son Gerard to the household, along with three servants, including their Italian born butler, Carlo Ambrosini.

The earliest reference to the Uthwatts at Ivy House comes in a passing reference to Mrs Uthwatt of Ivy House in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 13th, 1898, which reported on a “Sale of works” held in the village schoolroom in aid of a Church of England charitable endeavour to provide “home for waifs and strays.” Mrs Uthwatt, whom we can safely presume to be Anna Maria, was one of the stallholders.

In June 1902, the country was gearing up for the coronation of King Edward VII, but days before the ceremony was scheduled to take place on the 26th, the King came down with appendicitis. Faced with a dilemma as the King was gravely ill and the ceremony to be delayed, the village Coronation Committee elected to press on with the planned celebrations, but to scale back on the “more festive elements.” Croydon's Weekly Standard of July 5th reported that 130 children were nonetheless entertained to tea, and that Mrs Uthwatt of Ivy House provided Coronation mugs to all the attendees.

Gerard’s mother died in 1904, and he married on June 21st, 1905, to Frederica Gertrude Chapman Bouverie of Delapre Abbey, Northamptonshire. Plans to move out of Ivy House may have been underway in 1909, presaged by a sale of “surplus” furniture announced in the Wolverton Express of July 16th. Included were such items as lady’s and gent’s easy chairs, iron bedsteads and a whatnot, an open shelved display stand for ornamental objects.

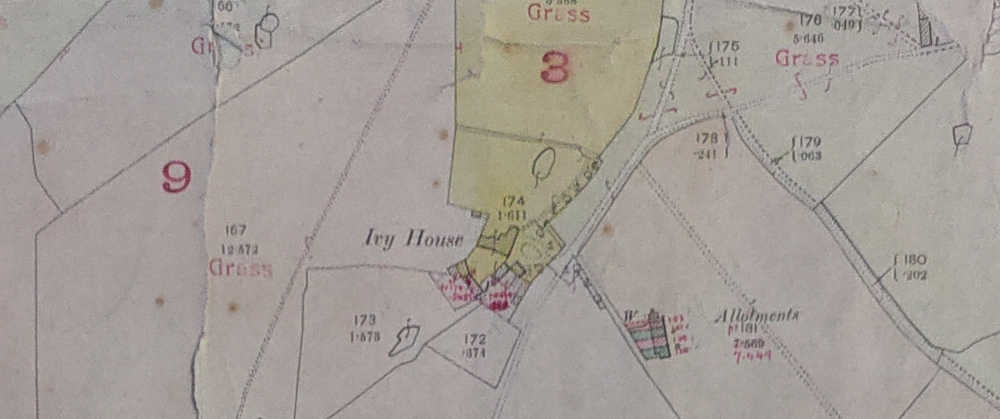

Throughout this period, no reference can be found to any farming activities, and if there were any it must have been the last, as the Valuation Office Survey map of 1910 (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5) proves. Ivy House is named and illustrated, owned by William Uthwatt, as is the associated parcel of land (highlighted yellow and numbered 3) associated with the house, though this has now shrunk to a little over five acres. Enough perhaps to paddock a few horses, or keep one or two dairy cows, but not nearly sufficient to be considered a farm. The greater balance of the land once associated with Ivy House had meanwhile been transferred into the ownership of "Grimes and Fowler", of Windmill Hill Farm on the High Street. However, as we will see, a connection to farming would be re-established to Ivy House in later years.

The earliest reference to the Uthwatts at Ivy House comes in a passing reference to Mrs Uthwatt of Ivy House in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 13th, 1898, which reported on a “Sale of works” held in the village schoolroom in aid of a Church of England charitable endeavour to provide “home for waifs and strays.” Mrs Uthwatt, whom we can safely presume to be Anna Maria, was one of the stallholders.

In June 1902, the country was gearing up for the coronation of King Edward VII, but days before the ceremony was scheduled to take place on the 26th, the King came down with appendicitis. Faced with a dilemma as the King was gravely ill and the ceremony to be delayed, the village Coronation Committee elected to press on with the planned celebrations, but to scale back on the “more festive elements.” Croydon's Weekly Standard of July 5th reported that 130 children were nonetheless entertained to tea, and that Mrs Uthwatt of Ivy House provided Coronation mugs to all the attendees.

Gerard’s mother died in 1904, and he married on June 21st, 1905, to Frederica Gertrude Chapman Bouverie of Delapre Abbey, Northamptonshire. Plans to move out of Ivy House may have been underway in 1909, presaged by a sale of “surplus” furniture announced in the Wolverton Express of July 16th. Included were such items as lady’s and gent’s easy chairs, iron bedsteads and a whatnot, an open shelved display stand for ornamental objects.

Throughout this period, no reference can be found to any farming activities, and if there were any it must have been the last, as the Valuation Office Survey map of 1910 (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5) proves. Ivy House is named and illustrated, owned by William Uthwatt, as is the associated parcel of land (highlighted yellow and numbered 3) associated with the house, though this has now shrunk to a little over five acres. Enough perhaps to paddock a few horses, or keep one or two dairy cows, but not nearly sufficient to be considered a farm. The greater balance of the land once associated with Ivy House had meanwhile been transferred into the ownership of "Grimes and Fowler", of Windmill Hill Farm on the High Street. However, as we will see, a connection to farming would be re-established to Ivy House in later years.

Major Harold Edward Charles Doyne Ditmas

That the Uthwatts still owned virtually every property in the parish gave them the pick of the finest houses, and by 1910, Gerard and his family had left Ivy House for Glebe House on the High Street. The new occupier of Ivy House (as confirmed by the Valuation Office Survey map of 1910) was the rather grand sounding Harold Edward Charles Ditmas, though he also went by the double-barrelled surname of Doyne-Ditmas. Born in Aldershot on April 19th, 1881, Harold had been a career soldier in the British Army, and prior to his arrival at Great Linford had served in India. He had married Sybil Harriet Monoux Payne at St. George church, Hanover Square in London, on December 5th, 1906, and the couple would go on to have three daughters and four sons. At the time of the marriage, Harold was a lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery.

Their first child, Eyvor Florence Sibyl was born at Kirkee, India on February 11th, 1908, but their next child Nancy Eileen entered the world at Great Linford on September 10th, 1909. Given that Gerard Uthwatt was selling his excess furniture in July 1909, this would seem to strongly indicate that the Ditmas family arrived at Ivy House between July and early September that year.

The 1911 census tells us that Harold, then aged 39, had retired and was living on “private means”, so did not need to trouble himself with any kind of commonplace work. A third daughter, Myra was born in 1911 at Great Linford, but family life was soon to be interrupted (as it was for so many others) by the outbreak of the first world war, with Harold returning to active service. He survived physically unscathed and returned a Major, but suffering from severe shellshock. Despite this, family life resumed at Great Linford with the birth of a first son to the couple, Philip in 1918.

In the early hours of the Monday morning of March 24th, 1919, Harold was roused by the choking smell of smoke. A furious fire was taking hold, the source identified rather ironically as a “smoking room.” Having evacuated his family and servants, Harold drove to Newport Pagnell to fetch the fire brigade, but by the time help arrived at around 5.30 in the morning, a full hour and a half after the blaze had first been detected, much of the building was alight, and only a fraction of the contents could be saved. By the time the fire brigade departed at 6.30pm, only the “morning room” remained unscathed. The fire was not without its casualties, three members of the fire brigade having been struck and injured to varying degrees by falling masonry when one of the chimneys collapsed.

We do not often get an insight into a person’s character, but Harold plainly felt some appreciation toward the men who had battled to save his house and made an attempt to show his gratitude. A note in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News (April 5th, 1919) reveals that he had paid all the expenses incurred by the Newport Pagnell Fire Brigade, and was also providing a fireman named Shelton 35 shillings a week while he recuperated from a broken arm suffered during the chimney collapse.

The calamity that had befallen the Ditmas family had robbed them of a roof over their head, but they must have quickly found temporary lodging in Newport Pagnell, as a second son, Derek, was born there toward the end of the year. However, though Ivy House was rebuilt, Harold and his family were never to return, with a permanent move taking place soon after to Wooten House in Bedford.

The 1911 census tells us that Harold, then aged 39, had retired and was living on “private means”, so did not need to trouble himself with any kind of commonplace work. A third daughter, Myra was born in 1911 at Great Linford, but family life was soon to be interrupted (as it was for so many others) by the outbreak of the first world war, with Harold returning to active service. He survived physically unscathed and returned a Major, but suffering from severe shellshock. Despite this, family life resumed at Great Linford with the birth of a first son to the couple, Philip in 1918.

In the early hours of the Monday morning of March 24th, 1919, Harold was roused by the choking smell of smoke. A furious fire was taking hold, the source identified rather ironically as a “smoking room.” Having evacuated his family and servants, Harold drove to Newport Pagnell to fetch the fire brigade, but by the time help arrived at around 5.30 in the morning, a full hour and a half after the blaze had first been detected, much of the building was alight, and only a fraction of the contents could be saved. By the time the fire brigade departed at 6.30pm, only the “morning room” remained unscathed. The fire was not without its casualties, three members of the fire brigade having been struck and injured to varying degrees by falling masonry when one of the chimneys collapsed.

We do not often get an insight into a person’s character, but Harold plainly felt some appreciation toward the men who had battled to save his house and made an attempt to show his gratitude. A note in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News (April 5th, 1919) reveals that he had paid all the expenses incurred by the Newport Pagnell Fire Brigade, and was also providing a fireman named Shelton 35 shillings a week while he recuperated from a broken arm suffered during the chimney collapse.

The calamity that had befallen the Ditmas family had robbed them of a roof over their head, but they must have quickly found temporary lodging in Newport Pagnell, as a second son, Derek, was born there toward the end of the year. However, though Ivy House was rebuilt, Harold and his family were never to return, with a permanent move taking place soon after to Wooten House in Bedford.

Philip Clayton Gambell

Ivy House must have risen from the ashes quite quickly, as the 1924 Kelly’s trade directory reveals a new occupant, Philip Clayton Gambell. He is listed alongside the local gentry, though he did have a trade, as an auctioneer. Philip had been born at Aston Rowant in Oxfordshire on September 26th, 1886, into a farming family, but he had settled into the career of an auctioneer by the time he was recorded on the 1911 census at Bushey in Hertfordshire. Of passing interest, he was visiting in the household of his future wife, Vida Marjorie Bristowe Webster. Also present was Vida's younger sister Dorothy, who had made a name for herself as a child singer and is still described as a singer in the census.

Philip and Vida married at Hendon in London in 1913, though Philip stated his address as the village of Willen in Buckinghamshire, not far from Great Linford. By the time of the 1921 census the family are residing at an unnamed house in Great Linford, though it must surely be Ivy House.

It was during the occupancy of the Gambells that the name of the house was changed to Elmhurst. Why the name was chosen cannot be discovered. The word seems to have no obvious connection or meaning to the Gambells and no historical antecedent in the parish. The name has been used for other houses in the UK and abroad, but this fact provides no additional provenance for the name. Precisely when the name was changed is uncertain, but we can narrow the probable date range down. It was still called Ivy House according to the 1924 Kelly's directory, a fact reflected in the 25 inch to the mile O.S map published in 1925, but in 1928, the Kelly's directory for Great Linford places Philip Clayton Gambell at Elmhurst.

Trade directories through to 1939 are consistent in naming the property Elmhurst, though there is a slight ambiguity introduced by the 1939 register, compiled as a form of mini census on the eve of the second world war. Though nearly illegible, it is possible to discern that the name was originally written as Ivy House, but then scratched out and replaced with Elmhurst, suggesting perhaps some lingering local knowledge of the earlier name. However, as we will discover later in this history, this was not quite the end of "Ivy House."

Tragedy struck in 1940, with the death of the Gambell's daughter Jean at Dallington, Northamptonshire. She was just 19 and noted as a talented tennis player who had competed at Wimbledon! Her probate record places her residence as Elmhurst. For more on Jean's's tennis career and tennis at Elmhurst, click here.

In 1949 a new Ordnance Survey map of Great Linford was produced, which clearly labels he house as Elmhurst. To the view the 1949 O.S. map, click here.

The Bucks Herald of November 30th, 1951, ran a front page story headlined “Surveyor acquitted at Winslow”, which if nothing else, must have proved very embarrassing to Philip. It was certainly a case that raised difficult questions about the limits of his sobriety, discovered by the police, asleep in a car at 3am in the morning with half consumed bottles of whiskey and sherry in arms reach.

The police seemed to have an open and shut case on their hands, yet despite witness testimony from the offices involved in the case, including that Philip had been observed driving erratically earlier in the evening and that alcohol could be smelt strongly on his breath, he somehow wiggled off the hook. He was “as sober as a judge” declared Philip to the bench, producing a witness who confirmed that when he had left his company at 1.40am, he had drunk only a cup of tea and was sober. The most interesting aspect of the case relates to a statement from the police that Philip had been sarcastic and facetious and had slurred his words, to which a doctor offered the novel defence that Philip was “eccentric in the extreme and his speech was usually slurred.” Somehow, sufficient doubt was sown that the bench dismissed the charge.

The following year a notice was published in the Wolverton Express of June 13th, which alongside a reminder of Philip’s regular business selling poultry, eggs and dairy produce by auction at Olney, also included notice of a forthcoming sale of “antique and modern household furniture and effects” at Elmhurst. The stated reason was that the items were “surplus to requirements owning to alterations to the house.” It seems an odd statement, as the list is long in the extreme and includes all manner of lots, from oak and walnut side tables to brass bedsteads and oriental carpets, even an electric washing machine. One of the more curious lots was a large quantity of unframed oil paintings by a W. B. Rowe. The only artist that can be identified by this name was an American who lived and worked in New York and Mexico, so how these came into Philip’s possession is intriguing, though as an auctioneer, doubtless many odd items passed though his hands.

The six inch to the mile 1952 O.S map labels the house as Elmhurst. This same year Philip retired, this important milestone commemorated in the Wolverton Express of November 28th. The article recaps the highlights of his life, including his sporting achievements, and the interesting fact that he was a founder member of the Bucks branch of the National Farmer’s Union, and was for 40 years their honorary secretary. So, although farming had long since ceased at Elmhurst, alongside his auction work, a farming connection of sorts had been maintained. Philip passed away on February 18th, 1954, at St. John’s Hospital in Northampton, aged 67. His funeral was held at Great Linford on Tuesday February 23rd, attended by “many members of the North Bucks farming community and business associates.” Sadly, Vida was unable to attend as she was unwell. Vida herself passed away on October 1st, 1964, at Tudor Cottage, Moulsoe. She had moved there by at least 1957, as it was reported that she had secured a rate rebate at the address.

While we cannot pinpoint the exact date of her departure, we can say with certainty that a Derrick Graves was resident at Ivy House as of October 1957. A brief story in the Bucks Standard of the 19th recounts that he had won £75 in a painting competition. His composition was entitled "To my wife" and had been whittled down to one of the 250 top works in an unspecified competition, from an initial pool of more than 3000 entries. So far however, this is the only reference thus far discovered to his presence at the house.

Meanwhile something rather unexpected had happened. Elmhurst appears at around this time to have reverted to the name Ivy House. This first becomes apparent due to an odd story of a prank gone wrong by a local farmer named Robert Scrimpton of Wood End Farm. The Wolverton Express of September 23rd, 1960, has the story, which concerns the disappearance of 10 sacks of potatoes from outside Ivy House. The location is described as on the road to Wood End Farm, so it seems entirely likely to be a renamed Elmhurst. As to the potatoes, Robert was brought up before the bench, but managed to convince the judge he had moved them as a joke. We might dismiss this lone reference to Ivy House as an aberration, but the 1972 O.S map makes matters incontrovertible, the property clearly labelled once again as Ivy House. This quite definitely is the house we have come to know as Elmhurst.

As the final part for now in this story, we also know the house had one final change to make, to Linford Lodge, not only a new name but a new purpose for the house as a restaurant. Little is presently known about this, other than its proprietors were a Dennis and Sally Ives. The restaurant was still trading until at least the mid 1980s, and though the precise date of closure is presently uncertain, for a long time the old sign still stood at the junction of Wood Lane and St Ledger Drive. Sadly it was in an increasingly decrepit state and finally collapsed in mid 2023. The house itself is now once again a private residence.

Philip and Vida married at Hendon in London in 1913, though Philip stated his address as the village of Willen in Buckinghamshire, not far from Great Linford. By the time of the 1921 census the family are residing at an unnamed house in Great Linford, though it must surely be Ivy House.

It was during the occupancy of the Gambells that the name of the house was changed to Elmhurst. Why the name was chosen cannot be discovered. The word seems to have no obvious connection or meaning to the Gambells and no historical antecedent in the parish. The name has been used for other houses in the UK and abroad, but this fact provides no additional provenance for the name. Precisely when the name was changed is uncertain, but we can narrow the probable date range down. It was still called Ivy House according to the 1924 Kelly's directory, a fact reflected in the 25 inch to the mile O.S map published in 1925, but in 1928, the Kelly's directory for Great Linford places Philip Clayton Gambell at Elmhurst.

Trade directories through to 1939 are consistent in naming the property Elmhurst, though there is a slight ambiguity introduced by the 1939 register, compiled as a form of mini census on the eve of the second world war. Though nearly illegible, it is possible to discern that the name was originally written as Ivy House, but then scratched out and replaced with Elmhurst, suggesting perhaps some lingering local knowledge of the earlier name. However, as we will discover later in this history, this was not quite the end of "Ivy House."

Tragedy struck in 1940, with the death of the Gambell's daughter Jean at Dallington, Northamptonshire. She was just 19 and noted as a talented tennis player who had competed at Wimbledon! Her probate record places her residence as Elmhurst. For more on Jean's's tennis career and tennis at Elmhurst, click here.

In 1949 a new Ordnance Survey map of Great Linford was produced, which clearly labels he house as Elmhurst. To the view the 1949 O.S. map, click here.

The Bucks Herald of November 30th, 1951, ran a front page story headlined “Surveyor acquitted at Winslow”, which if nothing else, must have proved very embarrassing to Philip. It was certainly a case that raised difficult questions about the limits of his sobriety, discovered by the police, asleep in a car at 3am in the morning with half consumed bottles of whiskey and sherry in arms reach.

The police seemed to have an open and shut case on their hands, yet despite witness testimony from the offices involved in the case, including that Philip had been observed driving erratically earlier in the evening and that alcohol could be smelt strongly on his breath, he somehow wiggled off the hook. He was “as sober as a judge” declared Philip to the bench, producing a witness who confirmed that when he had left his company at 1.40am, he had drunk only a cup of tea and was sober. The most interesting aspect of the case relates to a statement from the police that Philip had been sarcastic and facetious and had slurred his words, to which a doctor offered the novel defence that Philip was “eccentric in the extreme and his speech was usually slurred.” Somehow, sufficient doubt was sown that the bench dismissed the charge.

The following year a notice was published in the Wolverton Express of June 13th, which alongside a reminder of Philip’s regular business selling poultry, eggs and dairy produce by auction at Olney, also included notice of a forthcoming sale of “antique and modern household furniture and effects” at Elmhurst. The stated reason was that the items were “surplus to requirements owning to alterations to the house.” It seems an odd statement, as the list is long in the extreme and includes all manner of lots, from oak and walnut side tables to brass bedsteads and oriental carpets, even an electric washing machine. One of the more curious lots was a large quantity of unframed oil paintings by a W. B. Rowe. The only artist that can be identified by this name was an American who lived and worked in New York and Mexico, so how these came into Philip’s possession is intriguing, though as an auctioneer, doubtless many odd items passed though his hands.

The six inch to the mile 1952 O.S map labels the house as Elmhurst. This same year Philip retired, this important milestone commemorated in the Wolverton Express of November 28th. The article recaps the highlights of his life, including his sporting achievements, and the interesting fact that he was a founder member of the Bucks branch of the National Farmer’s Union, and was for 40 years their honorary secretary. So, although farming had long since ceased at Elmhurst, alongside his auction work, a farming connection of sorts had been maintained. Philip passed away on February 18th, 1954, at St. John’s Hospital in Northampton, aged 67. His funeral was held at Great Linford on Tuesday February 23rd, attended by “many members of the North Bucks farming community and business associates.” Sadly, Vida was unable to attend as she was unwell. Vida herself passed away on October 1st, 1964, at Tudor Cottage, Moulsoe. She had moved there by at least 1957, as it was reported that she had secured a rate rebate at the address.

While we cannot pinpoint the exact date of her departure, we can say with certainty that a Derrick Graves was resident at Ivy House as of October 1957. A brief story in the Bucks Standard of the 19th recounts that he had won £75 in a painting competition. His composition was entitled "To my wife" and had been whittled down to one of the 250 top works in an unspecified competition, from an initial pool of more than 3000 entries. So far however, this is the only reference thus far discovered to his presence at the house.

Meanwhile something rather unexpected had happened. Elmhurst appears at around this time to have reverted to the name Ivy House. This first becomes apparent due to an odd story of a prank gone wrong by a local farmer named Robert Scrimpton of Wood End Farm. The Wolverton Express of September 23rd, 1960, has the story, which concerns the disappearance of 10 sacks of potatoes from outside Ivy House. The location is described as on the road to Wood End Farm, so it seems entirely likely to be a renamed Elmhurst. As to the potatoes, Robert was brought up before the bench, but managed to convince the judge he had moved them as a joke. We might dismiss this lone reference to Ivy House as an aberration, but the 1972 O.S map makes matters incontrovertible, the property clearly labelled once again as Ivy House. This quite definitely is the house we have come to know as Elmhurst.

As the final part for now in this story, we also know the house had one final change to make, to Linford Lodge, not only a new name but a new purpose for the house as a restaurant. Little is presently known about this, other than its proprietors were a Dennis and Sally Ives. The restaurant was still trading until at least the mid 1980s, and though the precise date of closure is presently uncertain, for a long time the old sign still stood at the junction of Wood Lane and St Ledger Drive. Sadly it was in an increasingly decrepit state and finally collapsed in mid 2023. The house itself is now once again a private residence.