Sir William Prichard (Pritchard) and family of Great Linford and London

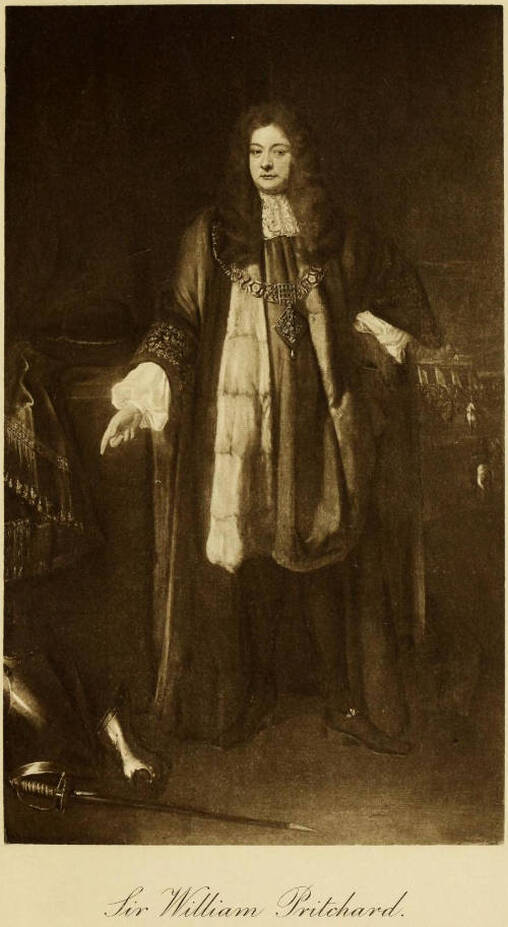

Sir William Prichard, painted circa 1693 by Godfrey Kneller. Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Sir William Prichard, painted circa 1693 by Godfrey Kneller. Internet Archive Book Images, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1678, William Prichard (also spelt Pritchard) purchased the land that would become modern day Great Linford Manor Park, the previous owner Thomas Napier having found himself mired in considerable debt. As well as carving out a career as a very successful London merchant, William served as the capital’s Lord Mayor and was elected to Parliament several times. Buying Great Linford Manor would have been highly symbolic of his ascendance from merchant to landed gentry, the acquisition of a country estate serving as a powerful statement of his great wealth and prestige.

William Prichard was born circa 1632 (we do not know precisely when or where), the first or second son (records are conflicting) of Francis Prichard and Mary (also called Maria.) Francis was of Welsh descent, but had moved to London, there to set up a rope making business from leased premises at Horsleydown in Southwark. William’s wife was the daughter of an Edward Eggleston, but of her family nothing else is presently known.

Francis and Mary had at least two sons and three daughters. A history of the Prichard family published in “Miscellanea Genealogica Et Heraldica vol. 1” published in 1874, reveals that their unmarried son Richard had been killed at sea fighting the Dutch at the age of 18. Their three daughters were Mary, Hannah and Martha. Mary married a John Uthwat (spelt unusually with one t) at Saint Olave’s Church, Southwark, on October 23rd, 1656; it was via their son Richard that the Great Linford estate would subsequently pass by inheritance into the hands of the Uthwatts.

We know little else of the Prichard family origins other than a suggestion that Francis was a, “descendant from Ruthergh ap Richard, who was seised of lands called Hendre, co. Carnavon.” Ap is a Welsh term meaning “son of”, so this somewhat archaic language tells us that Francis was related to someone called Ruthergh (Rhydderch in Welsh), a son of Richard. It is likely that the name Prichard (or Pritchard) arose from a contraction of “ap Richard.” “Seised” is a legal conveyancing term meaning ownership of the land in question, while Hendre is a word meaning “Old Farmstead.” This term can be found used all over Wales, so unfortunately the exact location of any Prichard property will likely have to remain a mystery.

The name Rhydderch is derived from "rhi" (ruler) and "derch" (exalted), so perhaps the Prichards were claiming some regal lineage. As for their standing in 17th century society, whilst it would be something of a cliche to say that William came from relatively humble origins, it is certainly fair to say that with his father’s move to London, his prospects were much improved.

However, rather than join his father in the family ropemaking business, William was instead apprenticed on October 6th, 1647, to an Abraham Manco of Southwark, thought to have been a member of the prestigious Merchant Taylors livery company. William would have been about fourteen or fifteen years old at the time.

William Prichard was born circa 1632 (we do not know precisely when or where), the first or second son (records are conflicting) of Francis Prichard and Mary (also called Maria.) Francis was of Welsh descent, but had moved to London, there to set up a rope making business from leased premises at Horsleydown in Southwark. William’s wife was the daughter of an Edward Eggleston, but of her family nothing else is presently known.

Francis and Mary had at least two sons and three daughters. A history of the Prichard family published in “Miscellanea Genealogica Et Heraldica vol. 1” published in 1874, reveals that their unmarried son Richard had been killed at sea fighting the Dutch at the age of 18. Their three daughters were Mary, Hannah and Martha. Mary married a John Uthwat (spelt unusually with one t) at Saint Olave’s Church, Southwark, on October 23rd, 1656; it was via their son Richard that the Great Linford estate would subsequently pass by inheritance into the hands of the Uthwatts.

We know little else of the Prichard family origins other than a suggestion that Francis was a, “descendant from Ruthergh ap Richard, who was seised of lands called Hendre, co. Carnavon.” Ap is a Welsh term meaning “son of”, so this somewhat archaic language tells us that Francis was related to someone called Ruthergh (Rhydderch in Welsh), a son of Richard. It is likely that the name Prichard (or Pritchard) arose from a contraction of “ap Richard.” “Seised” is a legal conveyancing term meaning ownership of the land in question, while Hendre is a word meaning “Old Farmstead.” This term can be found used all over Wales, so unfortunately the exact location of any Prichard property will likely have to remain a mystery.

The name Rhydderch is derived from "rhi" (ruler) and "derch" (exalted), so perhaps the Prichards were claiming some regal lineage. As for their standing in 17th century society, whilst it would be something of a cliche to say that William came from relatively humble origins, it is certainly fair to say that with his father’s move to London, his prospects were much improved.

However, rather than join his father in the family ropemaking business, William was instead apprenticed on October 6th, 1647, to an Abraham Manco of Southwark, thought to have been a member of the prestigious Merchant Taylors livery company. William would have been about fourteen or fifteen years old at the time.

The Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors

As an apprentice to a Merchant Taylor, William Prichard could himself expect to become a member, as indeed he did in 1655, rising to the rank of Master in 1673. Known originally as the Fraternity of St John the Baptist of Tailors and Linen-Armourers, the Merchant Taylors were and remain to this day one of the “Great 12 Livery Companies” of London. These companies began as fraternal organisations to protect and promote the interests of their members, each dedicated to a specific trade or profession, but many subsequently came to wield considerable power and influence over the social, economic and political fabric of the city.

When founded in 1327 the members were exclusively drawn from the community of tailors in the city, but as time went by, their membership began to diversify, with the appointment of noblemen, some noblewomen and several Kings of England as honorary members. As the company continued to prosper, a growing number of merchants and traders also joined its ranks, an expansion of membership that in 1503 saw the Tailors become the “Merchant Taylors.”

The confusing change in spelling from tailors to taylors can be traced to uncertainties in spelling and the medieval practice of substituting an “i” with a “y. By the time of the publication of Samuel Johnson’s famous dictionary in 1755 the spelling was standardised as tailor, but the Merchant Taylors have maintained the medieval spelling to this day.

When founded in 1327 the members were exclusively drawn from the community of tailors in the city, but as time went by, their membership began to diversify, with the appointment of noblemen, some noblewomen and several Kings of England as honorary members. As the company continued to prosper, a growing number of merchants and traders also joined its ranks, an expansion of membership that in 1503 saw the Tailors become the “Merchant Taylors.”

The confusing change in spelling from tailors to taylors can be traced to uncertainties in spelling and the medieval practice of substituting an “i” with a “y. By the time of the publication of Samuel Johnson’s famous dictionary in 1755 the spelling was standardised as tailor, but the Merchant Taylors have maintained the medieval spelling to this day.

William Prichard’s apprenticeship to Abraham Manco

There is no guarantee that Abraham Manco was a tailor; the various livery companies in London drew in members from numerous trades, but at present only tenuous hints exist as to Manco’s profession and what William’s apprenticeship would have entailed. An Abraham Manco (very likely the same man) can be found in several contemporaneous records as the co-owner of a ship called the William and Ralfe, which is recorded as having sailed to Virginia in 1649. One might then speculate that William was apprenticed as a clerk or accountant and that Manco was a trader, most likely in Tobacco. William appears to have completed his apprenticeship as he was “freed” on August 22nd, 1655; the average apprenticeship at the time lasting 7 years.

William Prichard, Ropemaker of Eltham

Both William’s parents had passed away whilst he was working for Manco, Francis in Southwark in 1651 and Mary the year before. Francis Pritchard’s will, written on December 14th, 1649 and proved October 10th, 1651, makes cash bequeathments to his son Richard and three daughters, but to William went the ropemaking business. It came however with the significant caveat that Mary Prichard would hold the lease until William was 21 (which would have occurred circa 1653) and until that time he would be expected to serve his mother without wage and allowed only, “meals drink apparel and lodging.” This rather parsimonious clause became moot of course, as Mary passed away herself in August of 1650.

What happened to the family ropeworks at Horsleydown is unknown, but certainly when next we find a reference to rope making, it is connection to a factory at Eltham in southeast London. Happily for the future of this new enterprise, William was able to gain a lucrative contract as, “rope and match-maker to the Ordnance”, which was the centre of government military procurement located at The Tower of London.

We do not know for sure when this contract was entered into, but he is identified in 1662 as one of, “The King’s Officers in the Tower”, as well as a constable of the parish, which means he was undertaking duties relating to the policing of the area. This information is gleaned from “A History of the Minories” by Edmund Murray Tomlinson, published in 1907. The Minories is an area of London adjacent to The Tower of London, in which William purchased a house.

We might have a clue as to how William gained the contract, though the marriage of his daughter Mary to John Uthwat, who was the Clerk of the Survey at Deptford Royal Navy Yard. His position required him to check the details of all stores received and issued, so potentially an ideal person to know if seeking a lucrative government contract.

What happened to the family ropeworks at Horsleydown is unknown, but certainly when next we find a reference to rope making, it is connection to a factory at Eltham in southeast London. Happily for the future of this new enterprise, William was able to gain a lucrative contract as, “rope and match-maker to the Ordnance”, which was the centre of government military procurement located at The Tower of London.

We do not know for sure when this contract was entered into, but he is identified in 1662 as one of, “The King’s Officers in the Tower”, as well as a constable of the parish, which means he was undertaking duties relating to the policing of the area. This information is gleaned from “A History of the Minories” by Edmund Murray Tomlinson, published in 1907. The Minories is an area of London adjacent to The Tower of London, in which William purchased a house.

We might have a clue as to how William gained the contract, though the marriage of his daughter Mary to John Uthwat, who was the Clerk of the Survey at Deptford Royal Navy Yard. His position required him to check the details of all stores received and issued, so potentially an ideal person to know if seeking a lucrative government contract.

Rope, match and warfare - the making of William Prichard's fortune

William’s contract to supply rope is self-explanatory enough, but match may require some elaboration. This was the nitrate impregnated cord used to fire guns, often carried wrapped around the wrist of a soldier with both ends smouldering. The idea was that if one end went out, it could be relit with the other, meaning a soldier was always likely to have a source of ignition close to hand for his firearm. It was said that a soldier on guard duty could burn through a mile of match a year! However, by the time William gained his contract, match was no longer used much for personal firearms, but continued to be used for cannon. Certainly it seems he was still supplying match in 1672, as upon his appointment to be a Sheriff of the city of London, he was described as, “serving cordage and matches to the Ordnance Office.”

Between 1652 and 1784 a series of conflicts were fought that became known as the Anglo-Dutch wars. It was against the background of these conflicts that William amassed a fortune as a supplier to The Ordnance, and as was noted previously, caused the death of his brother Richard. One must wonder if his zeal in prosecuting his business interests was in part motivated by a desire for revenge. Whatever the truth of the matter, his account with the bankers Clayton and Morris certainly showed a healthy balance, increasing from £7,000 in 1674 to £11,597 in 1678. This would be the equivalent in today’s money of about £1.3 million.

William also seems to have had a hand in a more tangible example of military procurement, as a contract dated 1672 and held by Hull University archives tells us that he was involved in the building of several buildings including a “Powder Tower”, used to store gunpowder. The site of this work is believed to be Tilbury Fort on the Thames.

Between 1652 and 1784 a series of conflicts were fought that became known as the Anglo-Dutch wars. It was against the background of these conflicts that William amassed a fortune as a supplier to The Ordnance, and as was noted previously, caused the death of his brother Richard. One must wonder if his zeal in prosecuting his business interests was in part motivated by a desire for revenge. Whatever the truth of the matter, his account with the bankers Clayton and Morris certainly showed a healthy balance, increasing from £7,000 in 1674 to £11,597 in 1678. This would be the equivalent in today’s money of about £1.3 million.

William also seems to have had a hand in a more tangible example of military procurement, as a contract dated 1672 and held by Hull University archives tells us that he was involved in the building of several buildings including a “Powder Tower”, used to store gunpowder. The site of this work is believed to be Tilbury Fort on the Thames.

Lord Mayor, Knight, Sheriff and Politician

As mentioned previously, William had become a parish constable, though for reasons that are unclear his appointment attracted the ire of Sir William Compton, the master of the Ordnance, such that he petitioned the Lord Mayor to have him removed from his duties. We do not know when this occurred or what the result was, but it must have been on or before 1663, as Compton died in October of that year. Undeterred from attaining high office, by 1672 William had been appointed a Sheriff of London, and that same year on October 28th, he was knighted. 1672 was clearly his year, as he was also appointed an Alderman of the City of London; the Court of Aldermen served as the upper house of city government, and met once a week.

In 1682 William was elected Lord Mayor of London though in circumstances that seemed far from unambiguous. As an Alderman and Tory his election should have been a mere formality, but he found himself facing two Whig opponents, and 56 votes short of a victory. A so called “scrutiny” was demanded, and in what one suspects was a blatant stitch-up, enough votes were found for William to be elected with a majority of 14. This result seemed to go down well with the King, who declared, ‘he would have the lord mayor presented to himself’ instead of to the lord chancellor, as he was ‘so well pleased with their choice of so honest and loyal a man’.

So despite the somewhat unorthodox method of his appointment, William’s “election” seemed one that was generally well received, for not only had the King given William his blessing, but it seemed he also enjoyed plenty of popular support, such that songs and poems were penned in celebration of his appointment. The words of the first two verses of one such song are reproduced below, to be sung to the tune of “Now, now the fight’s done” by Henry Purcell.

In 1682 William was elected Lord Mayor of London though in circumstances that seemed far from unambiguous. As an Alderman and Tory his election should have been a mere formality, but he found himself facing two Whig opponents, and 56 votes short of a victory. A so called “scrutiny” was demanded, and in what one suspects was a blatant stitch-up, enough votes were found for William to be elected with a majority of 14. This result seemed to go down well with the King, who declared, ‘he would have the lord mayor presented to himself’ instead of to the lord chancellor, as he was ‘so well pleased with their choice of so honest and loyal a man’.

So despite the somewhat unorthodox method of his appointment, William’s “election” seemed one that was generally well received, for not only had the King given William his blessing, but it seemed he also enjoyed plenty of popular support, such that songs and poems were penned in celebration of his appointment. The words of the first two verses of one such song are reproduced below, to be sung to the tune of “Now, now the fight’s done” by Henry Purcell.

THE CONTESTED SUBJECTS

or

THE CITIZENS' JOY.

Now, now the time's come, Noble Prichard is chose,

In spight of all people that would him oppose:

The King and His Subjects I hope will agree,

That troubles and dangers, forgotten may be;

Then now London Citizens merrily Sing,

God Bless Noble Prichard, and Prosper our King.

“The difference now I hope is Compos'd,

And the confidence that is in our Mayor Repos'd;

I do hope will be answer'd in every degree,

If so, then no subjects more happy than we;

Then brave London Citizens merrily Sing,

God Bless Noble Prichard, and Prosper the King.

or

THE CITIZENS' JOY.

Now, now the time's come, Noble Prichard is chose,

In spight of all people that would him oppose:

The King and His Subjects I hope will agree,

That troubles and dangers, forgotten may be;

Then now London Citizens merrily Sing,

God Bless Noble Prichard, and Prosper our King.

“The difference now I hope is Compos'd,

And the confidence that is in our Mayor Repos'd;

I do hope will be answer'd in every degree,

If so, then no subjects more happy than we;

Then brave London Citizens merrily Sing,

God Bless Noble Prichard, and Prosper the King.

If you would like to read the song lyrics in full, please click here for "The Contested Subjects"

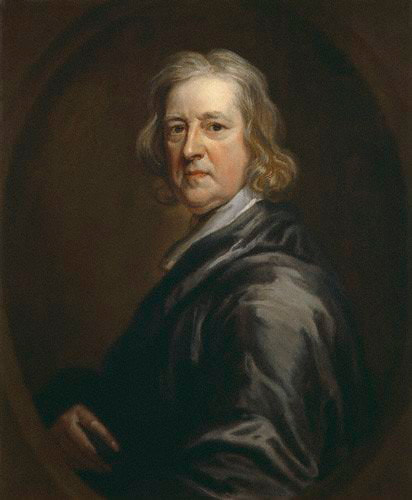

Thomas Papillon, who had Prichard arrested. Painting by Godfrey Kneller, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Papillon, who had Prichard arrested. Painting by Godfrey Kneller, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

These political machinations were being played out against the background of religious turmoil and furious plotting and scheming by Whig and Tory forces. Stuart era politics was nothing if not rambunctious; Prichard was confronted by Whig crowds in the first days of his mayoralty, who broke his windows! This political discord also underpinned a dispute that that saw William arrested in 1683 and left to languish in jail for six hours. The case stemmed from the actions of his predecessor as Mayor, who had refused to ratify (on the orders of King Charles II) the election of two men supported by the Whigs, Thomas Papillon and John Dubois, to the position of Sheriff. The impasse was still festering when William assumed the Mayoralty, such that Papillon had a writ drawn up to arrest him.

William's election had been fought against a broader contest sponsored by the King to wrest control of London from the Whig party, and William, a staunch Tory, was in the thick of this. He stubbornly continued the policy of his predecessor and did nothing to reverse the decision, despite writs been issued against him for "accepting false sheriffs." His eventual arrest became a significant cause celebre that would open a further can of worms; Richard Goodenough, counsel to Papillon and Dubois was amongst a group of men plotting an insurrection to assassinate the King, and Prichard!

William was clearly though a wily operator and having succeeded in having the charges dropped, felt sufficiently slighted to launch legal proceedings of his own against Papillon (Dubois had died), seeking £10,000 in damages for false arrest. The case duly came to court and William won, whereupon Papillon fled to Holland, not having the ready funds to make restitution. In a rather quaint rapprochement, William was to release Papillion from his debt in 1688, and the two men settled their differences and shook hands at Garraway's Coffee House in the City of London.

Perhaps awkwardly given their strained past, the pair were to cross paths again, as both men were elected to Parliament on several occasions, William for the first time in 1685 when James II was King. The History of Parliament website remarks that William was an “inactive member”, making little recorded contribution to affairs of state, though he was elected several times, losing his seat finally to a Whig challenger in 1695.

William's election had been fought against a broader contest sponsored by the King to wrest control of London from the Whig party, and William, a staunch Tory, was in the thick of this. He stubbornly continued the policy of his predecessor and did nothing to reverse the decision, despite writs been issued against him for "accepting false sheriffs." His eventual arrest became a significant cause celebre that would open a further can of worms; Richard Goodenough, counsel to Papillon and Dubois was amongst a group of men plotting an insurrection to assassinate the King, and Prichard!

William was clearly though a wily operator and having succeeded in having the charges dropped, felt sufficiently slighted to launch legal proceedings of his own against Papillon (Dubois had died), seeking £10,000 in damages for false arrest. The case duly came to court and William won, whereupon Papillon fled to Holland, not having the ready funds to make restitution. In a rather quaint rapprochement, William was to release Papillion from his debt in 1688, and the two men settled their differences and shook hands at Garraway's Coffee House in the City of London.

Perhaps awkwardly given their strained past, the pair were to cross paths again, as both men were elected to Parliament on several occasions, William for the first time in 1685 when James II was King. The History of Parliament website remarks that William was an “inactive member”, making little recorded contribution to affairs of state, though he was elected several times, losing his seat finally to a Whig challenger in 1695.

Prichard's support for the Glorious Revolution

King James II had assumed the crown in 1685, a Catholic King in a Protestant country. This deeply incongruous state of affairs was only tolerated because his daughter and heir Mary had been raised a devout Protestant, but when the King remarried and sired a son, this raised the very real likelihood that he would found a Catholic dynasty. This must have put William in a bind, not helped by the Kings efforts to ease the draconian restrictions that the state imposed on the Catholic faith. Behind the settling of William’s dispute with Thomas Papillon was the hand of James II, but when William refused to support an address on behalf of liberty for conscience, the King stripped him of all his London offices.

The so-called Glorious Revolution was a movement supported by a broad coalition of English politicians to invite the Dutch Protestant William of Orange and his wife Mary to invade and replace James II as dual monarchs, which they did in 1688. Given that he had lost a brother in the Anglo-Dutch wars it seems extraordinary that William would be part of this, but perhaps we can surmise something of his character from his decision. Was it simple level-headed pragmatism that motivated him, an instinct for survival in a dangerous world where you really could lose your head for backing the losing side (this was a battle not only for the religious soul of the nation, but between parliament and King) or were William's Protestant convictions so strongly held that he was willing to forgive and forget?

Whatever the reasons, clearly his support was substantive. As an active member of the Court of Common Council, the body of the City of London Corporation responsible for decision making, he sat on the committee which drew up a supportive address of welcome to William and Mary of Orange.

The so-called Glorious Revolution was a movement supported by a broad coalition of English politicians to invite the Dutch Protestant William of Orange and his wife Mary to invade and replace James II as dual monarchs, which they did in 1688. Given that he had lost a brother in the Anglo-Dutch wars it seems extraordinary that William would be part of this, but perhaps we can surmise something of his character from his decision. Was it simple level-headed pragmatism that motivated him, an instinct for survival in a dangerous world where you really could lose your head for backing the losing side (this was a battle not only for the religious soul of the nation, but between parliament and King) or were William's Protestant convictions so strongly held that he was willing to forgive and forget?

Whatever the reasons, clearly his support was substantive. As an active member of the Court of Common Council, the body of the City of London Corporation responsible for decision making, he sat on the committee which drew up a supportive address of welcome to William and Mary of Orange.

William Prichard buys Great Linford Manor

William’s motive for buying Great Linford Manor in 1678 can be seen in simple terms as the acquisition of a status symbol, but he may also have bought it to ensure that the family’s elevation from the merchant class to gentry was secured for his only son William. However, if this was the plan, it was cruelly wrecked with the death of William Jnr in 1685.

It has been suggested that William would not have spent much time at Great Linford, given his business and political obligations in London, but this seems unlikely given that aside from the £19,500 Purchase cost (approximately £2.2 million in modern money), he went on to demolish the old medieval manor in 1690 and build the core of the present manor house. We also have evidence for a terraced garden likely to have been constructed at around the same time, to which tally of work can also be added the Almshouses and school erected circa 1700. All told this was an enormous investment in time and money, and so it seems frankly inconceivable that William saw Great Linford as nothing more than a vanity project to sink his cash into, while leaving the Manor house empty or allowing someone else to live there as a tenant. It seems far more plausible to imagine that the Manor meant something to him, and he was after all buried in a vault (yet more expense) under St. Andrew’s Church.

It has been suggested that William would not have spent much time at Great Linford, given his business and political obligations in London, but this seems unlikely given that aside from the £19,500 Purchase cost (approximately £2.2 million in modern money), he went on to demolish the old medieval manor in 1690 and build the core of the present manor house. We also have evidence for a terraced garden likely to have been constructed at around the same time, to which tally of work can also be added the Almshouses and school erected circa 1700. All told this was an enormous investment in time and money, and so it seems frankly inconceivable that William saw Great Linford as nothing more than a vanity project to sink his cash into, while leaving the Manor house empty or allowing someone else to live there as a tenant. It seems far more plausible to imagine that the Manor meant something to him, and he was after all buried in a vault (yet more expense) under St. Andrew’s Church.

The Minories and Launderdale House

The Minories, Church of Holy Trinty.

The Minories, Church of Holy Trinty.

Great Linford Manor was not the Prichards’ only opulent residence. In 1673 William had purchased a house in The Minories, an ancient London parish named after an order of nuns known as the “Sorores Minores” or the Order of St. Clare. The order had arrived in London in 1293 from Paris, though it was actually founded in Italy in 1212.

A house in The Minories would have been highly convenient to William, as it was adjacent to the Tower of London, where he would have been conducting a lot of his business, and where, as was observed earlier, he maintained an office. It is also noteworthy that since at least 1562, The Minories had in large part been in the ownership of the crown for the use of the Ordnance, including as a munitions store. William’s close relationship with the Ordnance doubtless greased the wheels in obtaining his title to the property, which he purchased for £4,300 from Sir Thomas Chicheley, though it has been suggested that by a financial sleight of hand, the purchase price went directly to the crown.

The house was in a part of The Minories named Heydon Yard, so called after Captain John Heydon, a Master of the Ordnance. It was undoubtedly a posh part of the parish and was described as follows in A History of the Minories.

A house in The Minories would have been highly convenient to William, as it was adjacent to the Tower of London, where he would have been conducting a lot of his business, and where, as was observed earlier, he maintained an office. It is also noteworthy that since at least 1562, The Minories had in large part been in the ownership of the crown for the use of the Ordnance, including as a munitions store. William’s close relationship with the Ordnance doubtless greased the wheels in obtaining his title to the property, which he purchased for £4,300 from Sir Thomas Chicheley, though it has been suggested that by a financial sleight of hand, the purchase price went directly to the crown.

The house was in a part of The Minories named Heydon Yard, so called after Captain John Heydon, a Master of the Ordnance. It was undoubtedly a posh part of the parish and was described as follows in A History of the Minories.

|

Heydon Yard is broad enough for Coach or cart, at the upper end is a good large square or open place railed about with a row of Trees, very ornamented in the summer season, having on the east side coach houses and stables, on the West side a very handsome row of large houses, with Court Yards before them, and are inhabited by Merchants and persons of repute, on the North a square of good houses

|

Not content with his properties in the Minories and Great Linford Manor, in 1688 William also purchased Lauderdale House, located in what is now known as Waterlow Park in Highgate, North London. Built in 1582, it was considered one of the finest houses in Highgate. William purchased the property from the trustees of a bankrupt named John Hinde, but appears to have been the last owner/occupier of the property, as subsequently it was rented out. However, it remained in the hands of his heirs, the Uthwatts, for a number of generations. The house is now an arts and education centre.

William Prichard and St. Bartholomew's Hospital

William was president of St. Bartholomew’s hospital in London from 1688 until his death in 1704. The Henry VIII Gatehouse, which was rebuilt in 1702, carries an inscription naming Wm. Prichard as president. The Prichard family monumental inscription in St. Andrew’s Church at Great Linford also makes mention of his association with St. Bartholomew’s, specifically mentioning that, “hee erected a convenient apartment for cutting of the stone”, a reference to an early operating theatre that was concerned with removing gall, bladder and kidney stones. William’s will had specified that his estate go to St. Bartholomew’s in the event there were no heirs, though in the final event his two cousins, Daniel King and Richard Uthwatt were available.

The Almshouses and school at Great Linford

The Almshouses built circa 1700 and located in the grounds of Great Linford Manor Park have achieved what was very likely William’s intention, to leave a lasting monument to his charitable endeavours. The fact that he chose to locate them in line of sight of his manor house speaks volumes; he was surely making a highly visible statement.

The design of the Almshouses, and in particular the central Schoolhouse, is also worth remarking upon, as it is distinctly Dutch in character. This must be a nod to the arrival of William and Mary of Orange. Clearly then there was political capital to be gained in having his Almshouses designed in a manner likely to appeal to his new Monarchs, though of course we have no way of knowing if William and Mary of Orange were ever aware of Sir William Prichard's rather obsequious plans, though they may have been grateful for the loans he made to the government, totalling £6,000.

The design of the Almshouses, and in particular the central Schoolhouse, is also worth remarking upon, as it is distinctly Dutch in character. This must be a nod to the arrival of William and Mary of Orange. Clearly then there was political capital to be gained in having his Almshouses designed in a manner likely to appeal to his new Monarchs, though of course we have no way of knowing if William and Mary of Orange were ever aware of Sir William Prichard's rather obsequious plans, though they may have been grateful for the loans he made to the government, totalling £6,000.

William Prichard and the slave trade

If William Prichard had been apprenticed to a man trading with Virginia, he would almost certainly have been aware of the human misery that underpinned the Tobacco trade, which relied on slave holding plantations for its labour. Unfortunately we cannot be particularly charitable and say that he was an innocent bystander (if it is possible to be such a thing) in these matters, as it is a matter of record that William subsequently became a significant shareholder in one of the largest slave trading companies in the world, The Royal Africa Company.

This was not a passive investment (as if that could make it better); William served as one of 24 elected Assistants to the company in 1699-1700 and 1704,-4. He was also on the Governing Court of Committees for the East India Company in 1696-7 and 1698-1703, (with shares worth £15,000) an organisation with its own particularly cruel and capricious history of plunder, violence and political chicanery. The contrast between Sir William Prichard the builder of Almshouses and benefactor to hospitals and the merchant who invested his time and money in these blood soaked companies is certainly one that could vex psychologists.

This was not a passive investment (as if that could make it better); William served as one of 24 elected Assistants to the company in 1699-1700 and 1704,-4. He was also on the Governing Court of Committees for the East India Company in 1696-7 and 1698-1703, (with shares worth £15,000) an organisation with its own particularly cruel and capricious history of plunder, violence and political chicanery. The contrast between Sir William Prichard the builder of Almshouses and benefactor to hospitals and the merchant who invested his time and money in these blood soaked companies is certainly one that could vex psychologists.

An encounter with Samuel Pepys

The Diary of Samuel Pepys makes mention of two encounters with Sir William Prichard, in an entry dated Saturday 25 January 1667/68.

|

Up, and to the office, where busy all the morning, and then at noon to the ’Change with Mr. Hater, and there he and I to a tavern to meet Captain Minors, which we did, and dined; and there happened to be Mr. Prichard, a ropemaker of his acquaintance, and whom I know also, and did once mistake for a fiddler, which sung well, and I asked him for such a song that I had heard him sing, and after dinner did fall to discourse about the business of the old contract between the King and the East India Company for the ships of the King that went thither, and about this did beat my brains all the afternoon, and then home and made an end of the accounts to my great content, and so late home tired and my eyes sore, to supper and to bed.

|

Sarah Prichard, nee Cooke, wife of Sir Richard Prichard

William married Sarah Cooke some time before 1669, though we cannot be more precise than this, as a record for the marriage eludes detection at this time. We can hazard a guess as to how they met, as Sarah’s brother George lived in Eltham in Kent, where William had his rope works. The Dictionary of National Biography states that William and Sarah had three sons and a daughter, though this seems to be in error, as the impressive Prichard memorial in St. Andrew’s Church, Great Linford, makes explicit reference to an “only child” William, who died aged 16 in 1685.

Sarah was the daughter of Francis Cooke of Kingsthorpe in Northamptonshire, an attorney at law; of her mother, we know only that she also was called Sarah. The Cooke family appear to have been a fairly significant presence in Northamptonshire society for at least three centuries and were ardent benefactors to the church at Kingsthorpe. This charitable zeal was continued by Sarah after the death of William, reroofing at her own expense Kingsthorpe church, as well as installing new pews and repairing the leadwork. Similarly, in 1707 a major restoration took place at St. Andrews at Great Linford, again most likely paid for by Sarah. Her will also bequeathed 20 shillings per annum to the then rector of St. Andrews, on the express stipulation that he should not put, “any manner of beasts, sheep, hoggs, or other cattle into or on the churchyard, or any part thereof.”

Sarah appeared to live out her remaining years at The Minories in London (she passed away there in 1718) where she had continued her charitable activities, including a yearly sum of £32 bequeathed in her will and to be divided between “Ten poor Widows or Maids equally.” She also contributed in 1707 a payment of just over £100 toward the restoration of the parish church of Holy Trinity. Interestingly, we also find on the same list of benefactors the name of Daniel King (contributing £400), almost certainly Sir William’s nephew who had jointly inherited Great Linford Manor with Richard Uthwatt.

Sarah desired to be buried at Great Linford, and was duly interred there alongside her husband.

Sarah was the daughter of Francis Cooke of Kingsthorpe in Northamptonshire, an attorney at law; of her mother, we know only that she also was called Sarah. The Cooke family appear to have been a fairly significant presence in Northamptonshire society for at least three centuries and were ardent benefactors to the church at Kingsthorpe. This charitable zeal was continued by Sarah after the death of William, reroofing at her own expense Kingsthorpe church, as well as installing new pews and repairing the leadwork. Similarly, in 1707 a major restoration took place at St. Andrews at Great Linford, again most likely paid for by Sarah. Her will also bequeathed 20 shillings per annum to the then rector of St. Andrews, on the express stipulation that he should not put, “any manner of beasts, sheep, hoggs, or other cattle into or on the churchyard, or any part thereof.”

Sarah appeared to live out her remaining years at The Minories in London (she passed away there in 1718) where she had continued her charitable activities, including a yearly sum of £32 bequeathed in her will and to be divided between “Ten poor Widows or Maids equally.” She also contributed in 1707 a payment of just over £100 toward the restoration of the parish church of Holy Trinity. Interestingly, we also find on the same list of benefactors the name of Daniel King (contributing £400), almost certainly Sir William’s nephew who had jointly inherited Great Linford Manor with Richard Uthwatt.

Sarah desired to be buried at Great Linford, and was duly interred there alongside her husband.

William Pritchard’s final journey to Great Linford

William Prichard died aged 74 on or about February 18th, 1705 at The Minories; his body was then moved to his residence at Lauderdale House in Highgate, and thence to Great Linford. An abridged copy of his “funeral certificate” published in “Miscellanea Genealogica et Heraldica” in 1874 provides the following account of his funeral procession.

|

On Saturday, Feb. 24, his body was carried to his house at Highgate, co. Midd., and on the Monday following was set out there with all State befitting his degree till Wednesday, the last day of February, when, in a Herse, attended by 20 mourning coaches and six, in which were his relations, &c., the body was conveyed to his Manor of Great Linford, near Newport Pagnell, Bucks, where in his will he desired to be buried. Near Finchley Common most of the Coaches returned to London, & the rest proceeded with the body thro' Barnet, St. Albans, Hockley, Woburn & Newport Pagnell. At Hockley they were met by the Rev. Mr John Coles, Minister of Great Linford and about 30 of the defunct's tenants, who attended it to Linford Church, where about 6 in the evening of March 1st the service was read by Mr Coles and a sermon preached by the Rev. Lewis Atterbury, LL.D., Minister of Highgate, the body being placed in a vault made some years .ago under the North Aisle, about 8 in the Even.

|

The above account does not do full justice to the pomp and circumstance that occurred during the funeral service itself, to which we can turn to the following description carried in the book “Social life in Queen Ann’s Reign” by John Aston, published in 1904.

|

On Wednesday last the Corps of Sir William Prichard, Kt., late Alderman, and some- time Lord Mayor of the City of London, (Who died Feb. 18) having lain some days in State, at his House in Highgate, was convey'd from thence in a Hearse, accompanied by several Mourning Coaches with 6 Horses each, through Barnet and St. Albans to Dunstable; and the next day through Hockley (where it was met by about 20 Persons on Horseback) to Woburn and Newport Pagnell, and to his seat at Great Lynford (a Mile farther) in the county of Buckingham: Where, after the Body had been set out, with all Ceremony befitting his Degree, for near 2 hours, 'twas carried to the Church adjacent in this order, viz. 2 Conductors with long Staves, 6 Men in Long Cloaks two and two, the Standard 18 Men in Cloaks as before, Servants to the Deceas'd two and two, Divines, the Minister of the Parish and the Preacher, the Helm and Crest, Sword and Target, Gauntlets and Spurs, born by an Officer of Arms ; the Surcoat of arms born by another Officer of Arms, both in their rich Coats of Her Majesty's Arms embroider'd ; the Body, between 6 Persons of the Arms of Christ's Hospital, St. Bartholomew's, Merchant Taylors' Company, City of London, empaled Coat and Single Coat ; the Chief Mourner and his 4 Assistants, follow'd by the Relations of the Defunct, &c. After Divine Service was perform'd and an excellent Sermon suitable to the Occasion, preach'd by the Reverend Lewis Atterbury, LL.D., Minister of Highgate aforesaid, the Corps was interred in a handsome large Vault, in the Ile on the North side of the Church, betwixt 7 and 8 of the clock that Evening.

|

What an extraordinary pageant this must have been for the common folk of Great Linford. We are told that some 30 of William’s tenants attended the funeral, but one might sensibly presume those to have been the more affluent members of the parish; did the common folk feel compelled one wonders to line the High Street to show their respects, and did they drink to the memory of their Lord that evening?