The Story of St. Andrew's School

A bumpy start

Construction of St. Andrew's school had begun in 1874, and on Monday July 5th, 1875, headteacher Harry William Higham welcomed his first pupils to St Andrew’s school, with an average of 54 in attendance during the first week. Sadly, that same week, the following rather unflattering description was written in the school log book concerning their attainment. “The children are very backward – particularly in arithmetic – they know nothing of their tables or numeration and are very much given to copying.”

We also get a hint of the constant struggle faced by the school to maintain the consistent attendance of pupils, often caused by the demand of parents for their children to be available to work in the fields at crucial times of the year, but just as likely unpredictable weather or just plain old fashioned truancy. The 5th entry in the log book reads, “Ernest Johnstone ran home at play time in the morning – I sent boys to fetch him back – but his mother would not allow him to be brought.” No record was made of Mrs. Johnstone's objection.

A year later, the school received an inspection by a government inspector and as recorded in a log book entry dated June 26th, 1876, the results were far from flattering. “Received the following summary of H.M. Inspector’s report. This, the first Examination of the school has not produced good results. The master has had work before him to raise the School to a satisfactory standard of efficiency; at present it is weak and deficient in every detail.”

This had signalled the end for Harry Higham; his date of departure is noted in the Log Book as June 23rd, 1876, with a curt note that he has been “dismissed”, though the 1881 census finds him still holding down a job as a school master in Silverstone, Northamptonshire. He had been described on his appointment to St Andrews as a “certified teacher”, though a man of the same name, age and place of birth (Eydon in Northamptonshire) is listed in the 1891 census as a hawker; someone who peddled goods, generally door to door. There is something slightly odd about Harry, as it seems he was baptised as plain William Higham, but then added the forename Harry later in life.

St Andrew’s was closed a few days after his departure but with the observation that the services of a George. A. Davenport had been retained as master of the school, though it seems that before Mr Davenport assumed his post, a Martha Barnes was briefly in charge. However, no mention is made of her in the log book, and the only fleeting reference we find to her tenure is in the Harrod & Co’s 1876 Trade Directory for Buckinghamshire. Where then she fits into the chronology is uncertain, but it must have been a brief stay; she is to be later found on the 1881 census as mistress of the school in nearby Willen village.

We also get a hint of the constant struggle faced by the school to maintain the consistent attendance of pupils, often caused by the demand of parents for their children to be available to work in the fields at crucial times of the year, but just as likely unpredictable weather or just plain old fashioned truancy. The 5th entry in the log book reads, “Ernest Johnstone ran home at play time in the morning – I sent boys to fetch him back – but his mother would not allow him to be brought.” No record was made of Mrs. Johnstone's objection.

A year later, the school received an inspection by a government inspector and as recorded in a log book entry dated June 26th, 1876, the results were far from flattering. “Received the following summary of H.M. Inspector’s report. This, the first Examination of the school has not produced good results. The master has had work before him to raise the School to a satisfactory standard of efficiency; at present it is weak and deficient in every detail.”

This had signalled the end for Harry Higham; his date of departure is noted in the Log Book as June 23rd, 1876, with a curt note that he has been “dismissed”, though the 1881 census finds him still holding down a job as a school master in Silverstone, Northamptonshire. He had been described on his appointment to St Andrews as a “certified teacher”, though a man of the same name, age and place of birth (Eydon in Northamptonshire) is listed in the 1891 census as a hawker; someone who peddled goods, generally door to door. There is something slightly odd about Harry, as it seems he was baptised as plain William Higham, but then added the forename Harry later in life.

St Andrew’s was closed a few days after his departure but with the observation that the services of a George. A. Davenport had been retained as master of the school, though it seems that before Mr Davenport assumed his post, a Martha Barnes was briefly in charge. However, no mention is made of her in the log book, and the only fleeting reference we find to her tenure is in the Harrod & Co’s 1876 Trade Directory for Buckinghamshire. Where then she fits into the chronology is uncertain, but it must have been a brief stay; she is to be later found on the 1881 census as mistress of the school in nearby Willen village.

Holding on to a teacher

The aforementioned Mr Davenport joins the school on July 14th, 1876, and by July 6th the following year the next inspection offers a much rosier picture of things, with the observation made that, “The school has already improved under the new master. The children are neat and clean and the sewing is beginning to improve. There are not enough books for the use of the school. I am to state that more books should be provided at once.”

This entry also provides more of an insight into the rest of the teaching staff. George Henry Davenport is recorded as a certified teacher second class, and working alongside him is an A. A. Davenport, as well as a Mrs Davenport and 2 unpaid monitors. Clearly with so many Davenports this was a family affair, yet despite this useful information there is no clear sign of where they came from or went afterwards, but they seemed to be just what the school needed. Another glowing report followed in 1878, but then on September 26th that same year the Log Book records that George had tendered his resignation. This must have been a serious blow to the school managers, but they clearly moved quickly, as on October 7th the following entry is to be found in the log book.

This entry also provides more of an insight into the rest of the teaching staff. George Henry Davenport is recorded as a certified teacher second class, and working alongside him is an A. A. Davenport, as well as a Mrs Davenport and 2 unpaid monitors. Clearly with so many Davenports this was a family affair, yet despite this useful information there is no clear sign of where they came from or went afterwards, but they seemed to be just what the school needed. Another glowing report followed in 1878, but then on September 26th that same year the Log Book records that George had tendered his resignation. This must have been a serious blow to the school managers, but they clearly moved quickly, as on October 7th the following entry is to be found in the log book.

I took charge today of the school. There had been holiday all the previous week. The Rev S. H. Williams came in during the morning.

George H Munlow

Certified teacher 2nd class.

But George was gone before he could make any impression, departing after only a few months in the job; the school seemed to be struggling to retain a head teacher.

William Chetwynd arrives, and stays

On February 10th, 1879, William Chetwynd took up the post of head teacher, and would stay for much longer than any previous incumbent. William was a native of the splendidly named Baddesley Ensor, a village and parish in Warwickshire. His father Peter was a miner, but defying the class stereotypes of the time, he was clearly a man of some learning, as he was also the parish clerk. In 1871, we find William, then aged 14, as a school monitor, which clearly shows him to be a chip off the old block, and also implies that the school was operating under the so called monitorial system, in which the more able pupils taught the others in the class. If so, it seems to have been beneficial experience to William, as he was school master at Great Linford by at the age of 22; an impressive achievement for one so young.

But a penchant for teaching seems to have run in the family, as at Great Linford, William was joined by his elder sister Mary Ellen, aged 29, who was also recorded in the 1881 census as a teacher. A year later William married Sarah Ann Knight of Sherrington, settling down to become a prominent participant in village life; he played the organ at the church, was a cricketer and became chair of the Conservative and Unionist Club. He continued in his teaching position into 1891, where we find him on the census record along with his wife and two daughters, Sybil and Kathleen, both born in Great Linford. Sybil did not marry, but Kathleen did, to a Tom Durrant, with the couple subsequently emigrating to Canada, though tragically a son John would return as an airman and perish over the skies of Europe in World War 2.

William had an upward hill to climb, having inherited a struggling school. A summary of an inspection committed to the log book on October 11th, 1879 states, “The school is again in a very poor way. Changes of teacher and a recent epidemic of fever owing to which it was closed particularly account for this. Special attention is urgently required both as to discipline and attainments in the school generally, Better results of instruction and better discipline will be expected next year.”

But despite this poor start, William was recognised as qualified in the inspection, though it seemed he was not a natural disciplinarian; the following year’s inspection noted some improvement in attainment but added that, “discipline should be maintained with a firmer hand.” The inspection observes that William, his sister Mary and two unpaid monitors comprised the school staff. We also know from a later log book entry that his wife Sarah would fulfil the duty of sowing mistress.

In 1881 came good news. An inspection that was carried out on May 15th expressed in glowing terms the success of the school and reflected particularly well on William. “Mr Chetwynd is succeeding with the school. I am quite satisfied with the results of the examination, which are decidedly creditable. Mr Chetwynd will shortly receive his certificate.” Unusually, this entry is signed, by Sidney H Williams, “Correspondent for the school.” Sidney Herbert Williams was the Rector of St. Andrew’s Church.

A log book entry dated June 9th , 1884 provides evidence of another good inspection report on the school, and also adds a new and interesting name to the teaching staff. Annie Wells is described as a “pupil teacher” with responsibility for composition, geography and history. A “Pupil Teacher” was a form of apprenticeship that was first offered to middle class applicants in 1846 to bolster the supply of teachers. Initially this involved on the job training from the age of 13, but by the 1880s had evolved to include national instruction centres. Annie does not appear on either the 1881 or 1891 census for Great Linford, and nor is the name Wells one we can connect to the village; the log book entry indicates she is in her 3rd year, so she must have started after the April 3rd date of the 1881 census. An entry on June 15th, 1886 reveals that Annie has not been keeping up with her evening lessons for some time, especially Geography, but on July second the yearly summary of the school inspection provides the good news that Annie has qualified, but on the possibility that she might leave, a new girl called Ada Finch has entered into the school on her probationary period.

Unfortunately the 1885 report had marked something of a downturn in the proficiency of the school, and while the arithmetic and writing was deemed acceptable, the reading is described as not only, “expressionless and unintelligent”, but “a mechanical exercise.” In a punishment that seems counter to common sense, the grant for the infant’s class was reduced by one-tenth for neglect to provide books. But William appears to have turned things round by the following year, receiving again a good report with much improvement noted.

By the time of the 1887 inspection, Annie Wells has indeed left the school, and Ada Finch is settling in as the new pupil teacher. The school enters into a relatively settled period, with the log book full of the daily difficulties of running a school, including discipline and the perennial issue of attendance, which seems to have become something of an obsession for the school correspondents; not entirely unsurprising as visits by the attendance officer are frequent. By 1890, Ada has continued to progress toward her qualification and a new teacher has been added to the staff named miss E. Thomas, though she is gone by the following year, replaced by an Annie Mead. Annie we do find on the 1891 census, lodging on the High Street, so we know she was 22 years of age and had been born in Fenny Stratford.

Oddly, there seems to be no note made in the log book of William Chetwynd’s departure other than the observation that his daughter Kathleen was removed from the school register around the middle of December of 1892. We know that by 1899 he had attained a new post at Newbottle, Northamptonshire, as he is listed there in the Kelly's Directory of Beds, Hunts & Northants, but why he might have chosen to leave Great Linford is unknown.

But a penchant for teaching seems to have run in the family, as at Great Linford, William was joined by his elder sister Mary Ellen, aged 29, who was also recorded in the 1881 census as a teacher. A year later William married Sarah Ann Knight of Sherrington, settling down to become a prominent participant in village life; he played the organ at the church, was a cricketer and became chair of the Conservative and Unionist Club. He continued in his teaching position into 1891, where we find him on the census record along with his wife and two daughters, Sybil and Kathleen, both born in Great Linford. Sybil did not marry, but Kathleen did, to a Tom Durrant, with the couple subsequently emigrating to Canada, though tragically a son John would return as an airman and perish over the skies of Europe in World War 2.

William had an upward hill to climb, having inherited a struggling school. A summary of an inspection committed to the log book on October 11th, 1879 states, “The school is again in a very poor way. Changes of teacher and a recent epidemic of fever owing to which it was closed particularly account for this. Special attention is urgently required both as to discipline and attainments in the school generally, Better results of instruction and better discipline will be expected next year.”

But despite this poor start, William was recognised as qualified in the inspection, though it seemed he was not a natural disciplinarian; the following year’s inspection noted some improvement in attainment but added that, “discipline should be maintained with a firmer hand.” The inspection observes that William, his sister Mary and two unpaid monitors comprised the school staff. We also know from a later log book entry that his wife Sarah would fulfil the duty of sowing mistress.

In 1881 came good news. An inspection that was carried out on May 15th expressed in glowing terms the success of the school and reflected particularly well on William. “Mr Chetwynd is succeeding with the school. I am quite satisfied with the results of the examination, which are decidedly creditable. Mr Chetwynd will shortly receive his certificate.” Unusually, this entry is signed, by Sidney H Williams, “Correspondent for the school.” Sidney Herbert Williams was the Rector of St. Andrew’s Church.

A log book entry dated June 9th , 1884 provides evidence of another good inspection report on the school, and also adds a new and interesting name to the teaching staff. Annie Wells is described as a “pupil teacher” with responsibility for composition, geography and history. A “Pupil Teacher” was a form of apprenticeship that was first offered to middle class applicants in 1846 to bolster the supply of teachers. Initially this involved on the job training from the age of 13, but by the 1880s had evolved to include national instruction centres. Annie does not appear on either the 1881 or 1891 census for Great Linford, and nor is the name Wells one we can connect to the village; the log book entry indicates she is in her 3rd year, so she must have started after the April 3rd date of the 1881 census. An entry on June 15th, 1886 reveals that Annie has not been keeping up with her evening lessons for some time, especially Geography, but on July second the yearly summary of the school inspection provides the good news that Annie has qualified, but on the possibility that she might leave, a new girl called Ada Finch has entered into the school on her probationary period.

Unfortunately the 1885 report had marked something of a downturn in the proficiency of the school, and while the arithmetic and writing was deemed acceptable, the reading is described as not only, “expressionless and unintelligent”, but “a mechanical exercise.” In a punishment that seems counter to common sense, the grant for the infant’s class was reduced by one-tenth for neglect to provide books. But William appears to have turned things round by the following year, receiving again a good report with much improvement noted.

By the time of the 1887 inspection, Annie Wells has indeed left the school, and Ada Finch is settling in as the new pupil teacher. The school enters into a relatively settled period, with the log book full of the daily difficulties of running a school, including discipline and the perennial issue of attendance, which seems to have become something of an obsession for the school correspondents; not entirely unsurprising as visits by the attendance officer are frequent. By 1890, Ada has continued to progress toward her qualification and a new teacher has been added to the staff named miss E. Thomas, though she is gone by the following year, replaced by an Annie Mead. Annie we do find on the 1891 census, lodging on the High Street, so we know she was 22 years of age and had been born in Fenny Stratford.

Oddly, there seems to be no note made in the log book of William Chetwynd’s departure other than the observation that his daughter Kathleen was removed from the school register around the middle of December of 1892. We know that by 1899 he had attained a new post at Newbottle, Northamptonshire, as he is listed there in the Kelly's Directory of Beds, Hunts & Northants, but why he might have chosen to leave Great Linford is unknown.

A new husband and wife team

On January 10th, 1893, an entry in the log book records that Charles Thorne Wills and his wife Mary have taken up teaching duties at the school. Charles was 48 years old at the time and had been born at Stoke Damerel, a suburb of Plymouth in Devon. Mary was born 1843 in Llantrisant, Glamorgan, Wales. Married couples were clearly quite common in the teaching community, though it is interesting that Great Linford seemed willing (or had no choice) to cast a wide net to find teachers.

The first report under the Mills was a mixed bag, but even with allowances made for a “curtailed school year” and an epidemic of mumps, the intelligence of the children is deemed low, and Mr Mills is served notice that if there is no improvement by the next year, he will not be retained; a teacher’s life at this time seems something like a modern day football manager, with the threat of relegation and sacking never far from his mind. It does seem slightly unfair though, as Charles and Mary appear to be the sole teachers at this time, without even the help of a pupil teacher. Of related interest, Charles was himself a product of the pupil teacher system, and can be found in this role at Stoke Damerel on the 1861 census. Alas for Charles, and despite acknowledging that he is working at the school “single handed” (his wife seems not to count), the following year’s report offers him no comfort, and recommends his removal in favour of a more experience teacher.

However, either because the school managers decided to be charitable or were unable to find an immediate replacement, we find Charles still in his post in October of 1895, alongside a new infants’ teacher named Miss Hathaway. Mary Mills is listed as the sewing mistress. The situation remains unchanged in 1896, with another very poor report, but no recommendation as to the removal of Charles, but the writing was on the wall, and by January of 1897, there would be a new teacher in place.

The first report under the Mills was a mixed bag, but even with allowances made for a “curtailed school year” and an epidemic of mumps, the intelligence of the children is deemed low, and Mr Mills is served notice that if there is no improvement by the next year, he will not be retained; a teacher’s life at this time seems something like a modern day football manager, with the threat of relegation and sacking never far from his mind. It does seem slightly unfair though, as Charles and Mary appear to be the sole teachers at this time, without even the help of a pupil teacher. Of related interest, Charles was himself a product of the pupil teacher system, and can be found in this role at Stoke Damerel on the 1861 census. Alas for Charles, and despite acknowledging that he is working at the school “single handed” (his wife seems not to count), the following year’s report offers him no comfort, and recommends his removal in favour of a more experience teacher.

However, either because the school managers decided to be charitable or were unable to find an immediate replacement, we find Charles still in his post in October of 1895, alongside a new infants’ teacher named Miss Hathaway. Mary Mills is listed as the sewing mistress. The situation remains unchanged in 1896, with another very poor report, but no recommendation as to the removal of Charles, but the writing was on the wall, and by January of 1897, there would be a new teacher in place.

Edwin Whittaker takes over

Edwin Whittaker was another teacher born afar, this time Salford in Lancashire, but he didn’t have far to come at the time of his recruitment, as he was teaching at a private school of his own founding in Newport Pagnell. On the 1901 census we find him living at the old school house in Great Linford, aged 41. Like his predecessor he had married a local lass in 1886, in this case a Kate Kemp from Stantonbury, though for a time the couple left the parish to live in Thirwell, Cheshire. in 1891 William was still teaching in Thirwell while his wife and daughter were living with his in laws in New Bradwell, a pattern that continued in 1901 even when he had taken up his position at Great Linford. Only in 1911 do we find a census record with them both under the same roof at Great Linford.

Revealingly, a report dated Saturday January 18th, 1902 in Croydon’s Weekly Standard newspaper provides some confirmation that their daughter Kate spent (for reasons unknown) much of her life with her grandparents, but unfortunately the news related is of a tragic nature. Kate, or Kitty as we learn she was better known, had fallen gravely ill with an undisclosed malady some months previously and despite the best efforts of doctors had passed away on January 8th, aged 13 years, eight months. The article shows that there was a considerable outpouring of grief, with a long list of mourners provided. Kate was buried at St. James Churchyard in New Bradwell, but as befitting the description that, “in both parishes she was dearly loved”, the ceremony was conducted by the Reverend Turnbull of Great Linford. But even more tragically, this was not the first loss for the Whittakers. Though the various accounts of Kate’s death describe her as an only child, the 1911 Census tells a different story, as it provides for the opportunity for the respondent to state their number of children and how many are still living. The tally is two born, and two deceased. This leads to the discovery of a second daughter Gertrude Bessie, who had died in 1890 as a babe in arms at Thirwell.

But Edwin and Kate clearly did their best to rise above these twin tragedies; the aforementioned article of 1902 lauds Edwin as a, “much respected master” and various other newspaper accounts build a picture of a man who made an impact on the village and threw himself into a wide range of activities and interests. He was an accomplished organist for the church, organised popular entertainments in the village, could apparently hold a tune himself in concerts, was a committee member of the Newport Pagnell district union of teachers and in his role of honorary secretary of the local conservative association, was described as “indefatigable.” Mrs Whittaker features often in accounts as an equally formidable presence behind the scenes, organising and tending stalls.

Edwin was also in his post at an exciting time, as moves were afoot to extend the school. He was a busy organiser of various concerts and sales to raise funds, something that continued for several years before and after the construction was completed in 1905. We know from the Kelly’s Trade Directory of 1907 that the extension cost £900 and the school was then capable of accommodating up to 136 children, with an average attendance of 100.

Luckily, we have a very complete account of the new school, published December 30th, 1905 in Croydon's Weekly Standard newspaper.

Revealingly, a report dated Saturday January 18th, 1902 in Croydon’s Weekly Standard newspaper provides some confirmation that their daughter Kate spent (for reasons unknown) much of her life with her grandparents, but unfortunately the news related is of a tragic nature. Kate, or Kitty as we learn she was better known, had fallen gravely ill with an undisclosed malady some months previously and despite the best efforts of doctors had passed away on January 8th, aged 13 years, eight months. The article shows that there was a considerable outpouring of grief, with a long list of mourners provided. Kate was buried at St. James Churchyard in New Bradwell, but as befitting the description that, “in both parishes she was dearly loved”, the ceremony was conducted by the Reverend Turnbull of Great Linford. But even more tragically, this was not the first loss for the Whittakers. Though the various accounts of Kate’s death describe her as an only child, the 1911 Census tells a different story, as it provides for the opportunity for the respondent to state their number of children and how many are still living. The tally is two born, and two deceased. This leads to the discovery of a second daughter Gertrude Bessie, who had died in 1890 as a babe in arms at Thirwell.

But Edwin and Kate clearly did their best to rise above these twin tragedies; the aforementioned article of 1902 lauds Edwin as a, “much respected master” and various other newspaper accounts build a picture of a man who made an impact on the village and threw himself into a wide range of activities and interests. He was an accomplished organist for the church, organised popular entertainments in the village, could apparently hold a tune himself in concerts, was a committee member of the Newport Pagnell district union of teachers and in his role of honorary secretary of the local conservative association, was described as “indefatigable.” Mrs Whittaker features often in accounts as an equally formidable presence behind the scenes, organising and tending stalls.

Edwin was also in his post at an exciting time, as moves were afoot to extend the school. He was a busy organiser of various concerts and sales to raise funds, something that continued for several years before and after the construction was completed in 1905. We know from the Kelly’s Trade Directory of 1907 that the extension cost £900 and the school was then capable of accommodating up to 136 children, with an average attendance of 100.

Luckily, we have a very complete account of the new school, published December 30th, 1905 in Croydon's Weekly Standard newspaper.

The principal room of the original building has been divided with a glass panelled partition so as to provide an additional department for the classification of the elder children. This room has been extended by 26 feet. The infants’ department, which originally took up one end of the old school, has been abolished, and a new and thoroughly up-to-date classroom has been built for the use of the little ones. The room is lofty, is provided with plenty of light, and is ventilated so as to meet the requirements which modern science demands. The interior of the school has been painted light green and dark red, whilst the windows have been painted white. Cloak rooms have been provided for the children attending the school, and the lavatory accommodation has been considerably improved. The playground has yet to be asphalted, and other details will be attended to which will make the school modern in every particular. As a result of the alterations that are now nearing completion the school will accommodate 150 children.

Edwin Whittaker was one of the longest serving schoolmasters (in fact quite likely the longest serving) at Great Linford, working there until his retirement. He was still the schoolmaster listed in the Kelly’s Trade Directory of 1924 and is last seen as a retired School Master on the 1939 Register conducted on the eve of the second world war. By then, he and his wife were living in Woburn Sands. Meanwhile, we find a W E Keightly listed as the new schoolmaster in the 1928 Kelly’s Trade Directory, so we know roughly speaking that Edwin departed his post sometime between 1924 and 1928.

Mr Keightly, presuming he was a he, as the name does not figure further in the records so far examined, seems to have inherited a school in good health. The Reverend Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, in a letter he sent to the Buckingham Advertiser newspaper and published March 3rd 1928, takes polite exception to an article published by the paper in praise of record breaking attendance records in county schools, making the case that the school (both infants and mixed) at Great Linford had already achieved 100% attendance rates for several years running.

This letter also gives an insight into how closely the elite of the village were involved in shaping the lives of the inhabitants, especially when he talks approvingly of “parents cooperating”, which very likely refers to the difficulty of persuading poor parents to send their children to school rather than find work and bring in some additional income; it also has the ring of a man who expects as his due the obedience of his parishioners.

Aside from its academic purpose, the school was also a regular venue for the community to gather, with numerous concerts, talks and gatherings conducted there, notable among them the local Conservative Association, but it also provides an interesting window into other groups active in the village, such as a 1927 meeting of the Great Linford branch of the North Bucks Women’s Voters League, which tells us that the suffrage movement had a foothold in the village. Indeed, Frederica Gertrude Uthwatt of the Manor House was involved. Women of 30 years or older had won the vote in 1918, but it was not until 1928 that women of 21 years and upwards were afforded this right.

1921 had seen the passing of another education act, which raised the school leaving age from 11 to 14 years. What provision was immediately made for the children of Great Linford is not entirely clear, but it seems likely that for a time the older children remained with the school. Things changed in 1929, when it was agreed to apply to the board of education to transfer on March 1st, 1930 those children over the age of 11 to the school in Newport Pagnell, on the understanding that arrangements would be put in place to convey them there.

Mr Keightly, presuming he was a he, as the name does not figure further in the records so far examined, seems to have inherited a school in good health. The Reverend Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, in a letter he sent to the Buckingham Advertiser newspaper and published March 3rd 1928, takes polite exception to an article published by the paper in praise of record breaking attendance records in county schools, making the case that the school (both infants and mixed) at Great Linford had already achieved 100% attendance rates for several years running.

This letter also gives an insight into how closely the elite of the village were involved in shaping the lives of the inhabitants, especially when he talks approvingly of “parents cooperating”, which very likely refers to the difficulty of persuading poor parents to send their children to school rather than find work and bring in some additional income; it also has the ring of a man who expects as his due the obedience of his parishioners.

Aside from its academic purpose, the school was also a regular venue for the community to gather, with numerous concerts, talks and gatherings conducted there, notable among them the local Conservative Association, but it also provides an interesting window into other groups active in the village, such as a 1927 meeting of the Great Linford branch of the North Bucks Women’s Voters League, which tells us that the suffrage movement had a foothold in the village. Indeed, Frederica Gertrude Uthwatt of the Manor House was involved. Women of 30 years or older had won the vote in 1918, but it was not until 1928 that women of 21 years and upwards were afforded this right.

1921 had seen the passing of another education act, which raised the school leaving age from 11 to 14 years. What provision was immediately made for the children of Great Linford is not entirely clear, but it seems likely that for a time the older children remained with the school. Things changed in 1929, when it was agreed to apply to the board of education to transfer on March 1st, 1930 those children over the age of 11 to the school in Newport Pagnell, on the understanding that arrangements would be put in place to convey them there.

A number of documents concerning the day to day running of the school have survived, including the school log books, a punishment book and several photographs and documents. One such surviving piece of ephemera is the Merit Certificate below, issued in 1907 to Joseph Elliott. This we can ascertain to be the son of Frederick and Rebecca Elliott, who lived opposite the school, to the rear of Forge End Row on the High Street. in a house now long since demolished.

Some names of pupils can be gleaned from the log books, such as an entry dated May 16th. 1929. which records the names of those children who had received "Bishop's awards." The names to be discerned are: Mabel Garrett, Elsie Walker, Victor Lynham, Muriel Flute, May Robinson, Sidney Mills, Roland Field, Stella Temple, Frances Hayfield, Olive Kemp, Vera Sapwell, William Temple, Joseph Chamberlain, John Barratt, Thomas Robinson, Doris Ackinson and Doris Walters.

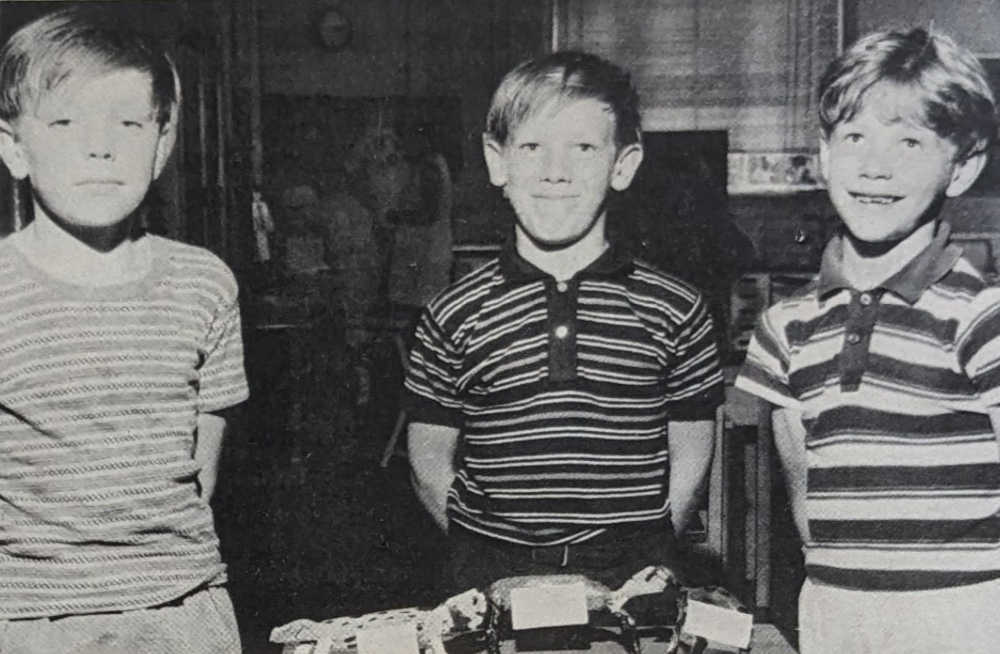

As it happens, that same year, the class photograph below was taken, so we can presume some at least of the names above are represented, though it should be noted the logbook records approximately 60 pupils registered that year with the school.

As it happens, that same year, the class photograph below was taken, so we can presume some at least of the names above are represented, though it should be noted the logbook records approximately 60 pupils registered that year with the school.

In addition to the 17 names above, local sources can add the additional name George Willett, as well as identifying that Olive Kemp is the girl on the far left of the back row. Oddly, though the logbook for 1929 provides a great many notes on the day to day activities in the school, no evidence can be discerned to say on what date the picture was taken.

On the eve of war in 1939, a national register was compiled of the country's population, which gives us a few potential clues as to the people in the village connected to the school. Eliza Turner, born April 29th, 1875 is described as wife of school caretaker, at number 10 Council House. Oddly, the person on the register presumed to be her husband, Thomas Turner, is described as a general labourer (retired), not as expected a school caretaker.

Additionally, a Lilian G. Fuller is listed as a certified elementary school teacher, living at the Rectory. This is not that surprising, as the school was of course Church of England, so Lilian lodging at the Rectory makes sense. Born on April 12th, 1883, in Islington, London, Lillian Gertrude Fuller was the daughter of Johnathan and Sarah Fuller. Her father was a silversmith and clerk at Goldsmith's Hall, the Assay office responsible for hallmarks. In 1891, both Lilian and her sister Margaret were working in London as teachers. We do not know when Lilian arrived at Great Linford, though she was at Acton Lane Council School in Willesden in 1921, listed as such on the census that year. Lilian never married, and passed away in London in 1970.

Reports on the activities at the school are presently lacking for the next few decades, but The Bucks Standard of July 23rd, 1960 carries a short report on an open day, the subject of which suggests the village was still very much a farming community.

On the eve of war in 1939, a national register was compiled of the country's population, which gives us a few potential clues as to the people in the village connected to the school. Eliza Turner, born April 29th, 1875 is described as wife of school caretaker, at number 10 Council House. Oddly, the person on the register presumed to be her husband, Thomas Turner, is described as a general labourer (retired), not as expected a school caretaker.

Additionally, a Lilian G. Fuller is listed as a certified elementary school teacher, living at the Rectory. This is not that surprising, as the school was of course Church of England, so Lilian lodging at the Rectory makes sense. Born on April 12th, 1883, in Islington, London, Lillian Gertrude Fuller was the daughter of Johnathan and Sarah Fuller. Her father was a silversmith and clerk at Goldsmith's Hall, the Assay office responsible for hallmarks. In 1891, both Lilian and her sister Margaret were working in London as teachers. We do not know when Lilian arrived at Great Linford, though she was at Acton Lane Council School in Willesden in 1921, listed as such on the census that year. Lilian never married, and passed away in London in 1970.

Reports on the activities at the school are presently lacking for the next few decades, but The Bucks Standard of July 23rd, 1960 carries a short report on an open day, the subject of which suggests the village was still very much a farming community.

Tuesday was Open Day at Great Linford Primary School, and parents and friends went to see the work which had been done during the year.

The Juniors had taken "wool" as their project and the finished show was most interesting. Included in this were paintings of sheep, a plan of Great Linford with its farms, the story of sheep, wool clippings right up to weaving and knitting of wool.

Interesting too was the scrap book made of material with appliqued pictures.

The infants had produced models of nursery rhymes - Humpty Dumpty, Old Mother Hubbard, Little Miss Muffet, etc.

Prizes were presented to Patricia Chew, Jill Chamberlin, Beryl Riddy.

However, as reported in the Bucks Standard of June 10th, 1961, the school's future was in doubt. The Diocesan Council for Education had approached Bucks Education Committee to raise the question of the future of the school, as pupil numbers had been declining in recent years, and presently stood at just 24. However, though numbers were not expected to exceed much above 30 in the coming years, the North Bucks Divisional Education Committee opinioned that it was desirable for the school to remain open.

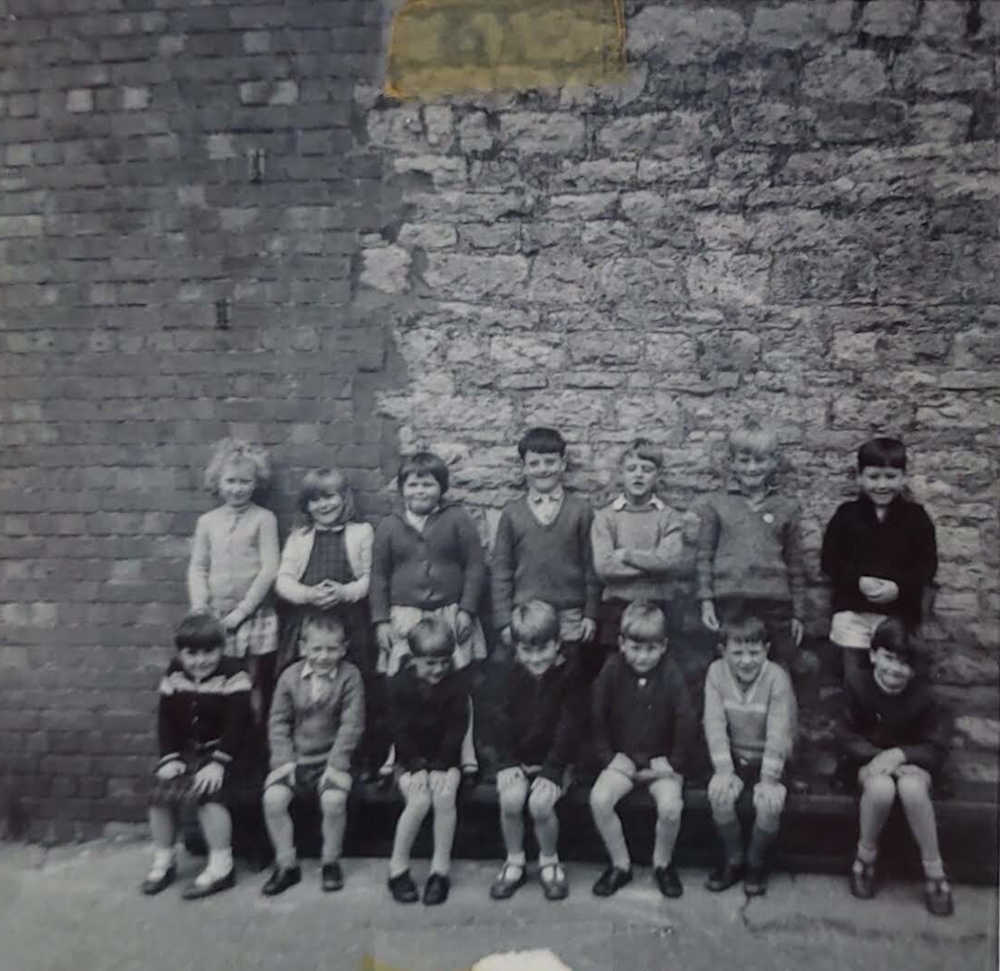

Several photographs have come to light purported to be taken in 1966. The class photograph reproduced below is a slightly curious one, as the wall used as a backdrop has no obvious modern analogue in the village. Unfortunately, the pupils are presently unidentified.

Several photographs have come to light purported to be taken in 1966. The class photograph reproduced below is a slightly curious one, as the wall used as a backdrop has no obvious modern analogue in the village. Unfortunately, the pupils are presently unidentified.

Poor condition

A report carried in The Wolverton Express newspaper of April 19th, 1966 announced the proposed allocation of £13,000 for improvements to the school. Having examined the situation, Mrs Lovelock-Jones of the Bucks Education Committee was of the opinion that the school "was in such a very poor condition that the sub-committee felt something must be done straight away."

Parents complain

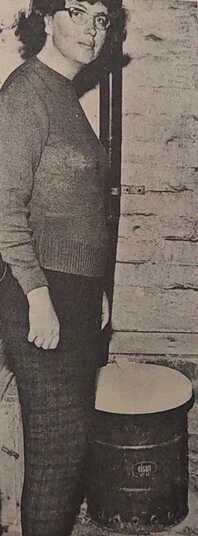

Laura Dyer shows a Bucks Standard Reporter the poor state of the lavatories in 1966.

Laura Dyer shows a Bucks Standard Reporter the poor state of the lavatories in 1966.

At some point prior to 1966, Bucks County Council has taken over responsibility for the school from the church authorities, at which time a programme of modernisation of the buildings and facilities was reported to have been a priority. However, complaints had been levelled at the school authorities, including threats to withhold children from attending classes, by parents concerned at the poor state of the toilets. A front page article in The Bucks Standard of July 29th described a tin shed with a half a roof and two Elsan chemical toilets, so poorly maintained that in winter it rained and snowed through the roof, and in summer the toilets smelt horrible.

Though an improvement plan appears to have been put in place by the local education authority, little progress had been made, and indeed one mother speaking to the newspaper recalled that this state of affairs had persisted from at least 1950, when her daughter had attended the school. The headmistress, Mrs M. K. Nash, sided with the feelings of the parents, whom she said considered the toilets to be "museum pieces."

Two of the concerned parents, Mrs. Jane Organ of 4, Church Farm Crescent, and her neighbour Mrs. Jane Webb, had sent letters to the Education authority, though professed little hope of their effectiveness, hence the threat to withhold their children from attending. Mrs. Laura Dyer, with two children at the school, had organised a petition, which had been signed by almost all the parents in the village. This she had sent to the Divisional Education Office.

The article offers no clue as to the resolution of the problem, and the education authorities appear not to have been asked to comment, but it is shocking to consider that as late as 1966, the facilities in a village school could still be so primitive.

Though an improvement plan appears to have been put in place by the local education authority, little progress had been made, and indeed one mother speaking to the newspaper recalled that this state of affairs had persisted from at least 1950, when her daughter had attended the school. The headmistress, Mrs M. K. Nash, sided with the feelings of the parents, whom she said considered the toilets to be "museum pieces."

Two of the concerned parents, Mrs. Jane Organ of 4, Church Farm Crescent, and her neighbour Mrs. Jane Webb, had sent letters to the Education authority, though professed little hope of their effectiveness, hence the threat to withhold their children from attending. Mrs. Laura Dyer, with two children at the school, had organised a petition, which had been signed by almost all the parents in the village. This she had sent to the Divisional Education Office.

The article offers no clue as to the resolution of the problem, and the education authorities appear not to have been asked to comment, but it is shocking to consider that as late as 1966, the facilities in a village school could still be so primitive.

That things must have moved ahead by the following year is suggested by an article in the Wolverton Express of May 26th, but the headline "Further delay at Great Linford school" has an ominous ring, and indeed the article goes on to explain that "The school should have been ready, all spick and span for the re-opening after the Easter holiday on April 6th. The children could not even get back to school until the 10th and even now the work is not finished and there is particular delay over the canteen facilities." At a meeting of the North Bucks Divisional Executive it was observed that the children had to eat their meals in one of the classrooms, but the suggestion of the provision of a dining hall was dismissed for lack of funds.

Despite the difficulties the school was facing, there were clearly strong efforts made to foster an interesting and engaging environment for its pupils, as demonstrated by an article carried in the Bucks Herald of July 18th 1969, concerning an open day. The children had made a variety of Papier-mâché displays, including a model of an Apollo astronaut named archie, as well as monsters and dragons. Also on display were various other handicraft works. Pupils named in the article are Phillip Dyer, Leslie Thompkins, Grant Smith, Brenda Lucock, Judith Pye, Thelma Bates, Mandy Kemp and Diana Chew.

Despite the difficulties the school was facing, there were clearly strong efforts made to foster an interesting and engaging environment for its pupils, as demonstrated by an article carried in the Bucks Herald of July 18th 1969, concerning an open day. The children had made a variety of Papier-mâché displays, including a model of an Apollo astronaut named archie, as well as monsters and dragons. Also on display were various other handicraft works. Pupils named in the article are Phillip Dyer, Leslie Thompkins, Grant Smith, Brenda Lucock, Judith Pye, Thelma Bates, Mandy Kemp and Diana Chew.

The school was clearly well supported locally, as is illustrated by an article in the Bucks Standard of October 23rd, 1970, concerning the annual jumble sale. "The people of the village rallied around", with £25 raised. Teas were served by Mrs. Riddy and Mrs. Smith, and helping at various other stalls were Mrs. Brandon, Mrs. Hayfield, Mrs. Lewes and Mrs. Seamarks. Mrs. J. Russell organised a prize of a box of groceries, which was won by Mrs. Hefferon. Mrs. Barley won the guess the weight of the cake competition.

A report on the school's Christmas activities carried in the January 1st, 1971 edition of the Bucks Standard tells us that the headmistress at this time was a Mrs. Russell, noting that she and the children had toured the village to sing carols by lantern light. In addition, a concert was put on for parents and friends, with three plays performed; "The magic pillar box" by the infants, "Getting ready for Christmas" by the juniors, and a nativity play by all the children. A "magnificent tea" was provided by the parents, and served by "Mesdames Pye, Riddy, Willett, Hayfield, Seamarks and Smith." The reverend Waterman entertained the children.

A ripple of panic went through the village in 1971, as reported in the Bucks Standard of April 16th. Rumours had begun to spread that the school was to close, a curious decision if true, as the article observes that "a considerable sum of money has been spent in modernising the village school." As it happens, the rumours were false, prompted by a mix up regarding a school in Stantonbury.

A sports day and gala held on July 3rd, 1971 was celebrated in the Bucks Standard of the 9th, The father's race was won by Mr. Thompkins, the mother's race by Mrs. Lever, and the family race by Mr. and Mrs. Thompkins and Ross. A football match between father's and sons was won by the dads, four goals to three.

A report on the school's Christmas activities carried in the January 1st, 1971 edition of the Bucks Standard tells us that the headmistress at this time was a Mrs. Russell, noting that she and the children had toured the village to sing carols by lantern light. In addition, a concert was put on for parents and friends, with three plays performed; "The magic pillar box" by the infants, "Getting ready for Christmas" by the juniors, and a nativity play by all the children. A "magnificent tea" was provided by the parents, and served by "Mesdames Pye, Riddy, Willett, Hayfield, Seamarks and Smith." The reverend Waterman entertained the children.

A ripple of panic went through the village in 1971, as reported in the Bucks Standard of April 16th. Rumours had begun to spread that the school was to close, a curious decision if true, as the article observes that "a considerable sum of money has been spent in modernising the village school." As it happens, the rumours were false, prompted by a mix up regarding a school in Stantonbury.

A sports day and gala held on July 3rd, 1971 was celebrated in the Bucks Standard of the 9th, The father's race was won by Mr. Thompkins, the mother's race by Mrs. Lever, and the family race by Mr. and Mrs. Thompkins and Ross. A football match between father's and sons was won by the dads, four goals to three.

Despite it being a wet day, a jumble sale held on October 16th, 1971 raised £27.60 1/2p for the school. Teas were served by Mrs. Riddy and Mrs. Willett. Mrs. Busby, Mr. and Mrs. Berry, Mrs. Dyer, Mrs. Hayfield, Misses R and E Lever and Mrs. J. Willson were all kept busy on the day.

In February 1972, a tree planting event was organised in the village, with pupils from St. Andrews participating. A variety of trees were planted, including two cherry trees. named by the children as Kathleen and Dulcie, after their teachers. The tree planting was part of a programme inspired by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation's stated aim of creating a city of trees. It was also hoped that by involving the children, a sense of ownership would be instilled, reducing the chances of future vandalism. That there are two trees on the street in the position indicated in the picture below, seems to have vindicated this approach. John Rowland, a member of the forestry team for the Milton Keynes Development Corporation, told a reporter for the Bucks Standard that Great Linford was the first place in the city to have participated, with others to follow. The newspaper article also names the then headmistress of the school as Mrs R. M. Russell.

In February 1972, a tree planting event was organised in the village, with pupils from St. Andrews participating. A variety of trees were planted, including two cherry trees. named by the children as Kathleen and Dulcie, after their teachers. The tree planting was part of a programme inspired by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation's stated aim of creating a city of trees. It was also hoped that by involving the children, a sense of ownership would be instilled, reducing the chances of future vandalism. That there are two trees on the street in the position indicated in the picture below, seems to have vindicated this approach. John Rowland, a member of the forestry team for the Milton Keynes Development Corporation, told a reporter for the Bucks Standard that Great Linford was the first place in the city to have participated, with others to follow. The newspaper article also names the then headmistress of the school as Mrs R. M. Russell.

A newspaper report from October 26th, 1979, concerns a half term concert, in which the children presented their own version of Jack and the Beanstalk. The article also mentions that St. Andrew's was one of those threatened with closure, but with 43 pupils on the present roster and the school fully booked until 1986, its future appeared secure.

In February 1981, the school was the recipient of an adventure playground for the 48 pupils then enrolled. The new equipment had been procured by a coalition of local organisations; the parish council, church charities and parents and friends of the school. Speaking of the planning that had gone into the installation, headteacher Margarer Tugwell was reported as saying, "The money needed was raised very quickly, and we managed to keep the plan quiet from the children. We were pleased, but to see their faces, you would think we had given them the moon." As previously mentioned, the school appears to have overcome some of its problems attracting students, as the report mentions that there was a waiting list.

For a time, the school had its own on site open air swimming pool. There seems to have been plans to make this a more permanent fixture for the school, as drawings produced in 1980 show plans to enclose the pool in it's own building. Presumably this plan did not come to fruition.

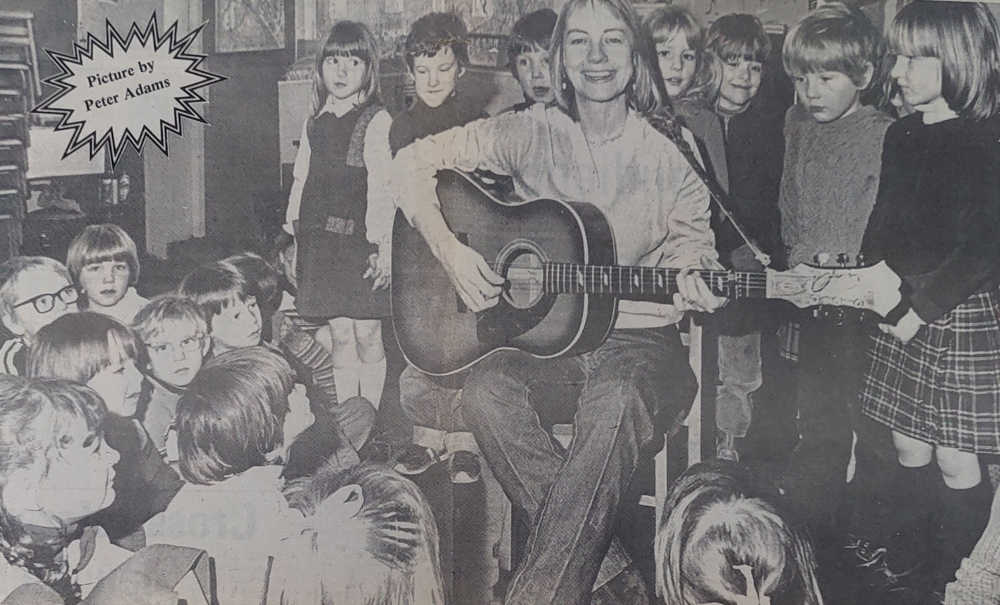

In 1981, the folk singer Saffron Summerfield visited the school and received an enthusiastic reception from the children, who wrote thank you letters to her.

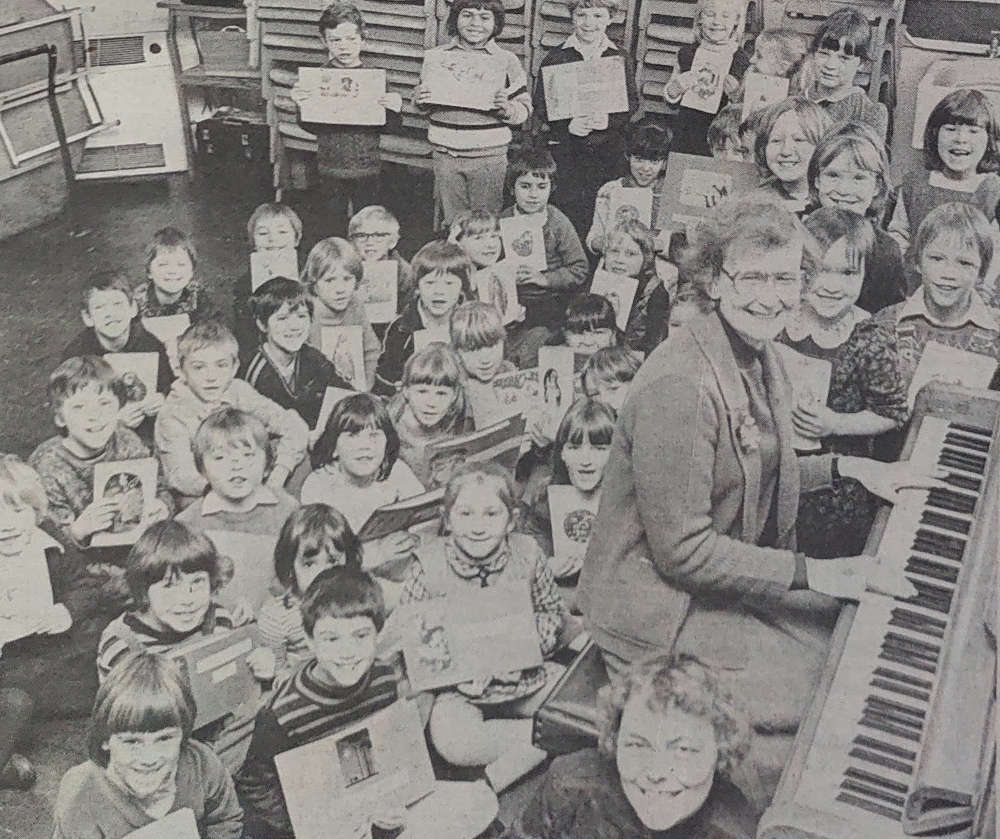

Undated photograph of school staff of St. Andrews.

Undated photograph of school staff of St. Andrews.