The Congregational Chapel at Great Linford

St. Andrews Church has long been the very visible symbol of religious orthodoxy in the parish, but not everyone has accepted that authority and Great Linford has had its fair share of so called dissenters, men and women who refused to abide by the rules of the established church. A History of the County of Buckinghamshire published in 1831 makes mention that there were several “unendowed” dissenting meeting houses in the parish; by unendowed, it appears to be making reference to the lack of any financial support, so these would have literally been the personal abodes of people willing to host meetings.

But this was to change shortly afterward due to the generosity of a man named George Osbourne, who caused the Chapel on the High Street to be constructed in 1833. His name comes to light from an article published in the September 1st, 1906 edition of Croydon’s Weekly Standard newspaper, which reports on the recently completed renovation of the Chapel. This articles also provides an illuminating history of what the article calls “Congregationalism” in Great Linford and serves to push back the date of the movement in the village to 1813, worth then reproducing the following extract.

After being in the builder’s hands for renovation and repair for nearly two months, the Congregational Chapel at Great Linford was re-opened for public service on Saturday, August 25. The history of Congregationalism in the village is an interesting one and goes back to the year 1813, when services were first held in a cottage. For nearly 20 years a little band of enthusiastic workers continued their labours, holding meetings in this way until in 1832 a generous gift by Mr. Osborne of a piece of land enabled the present chapel to be built. In its early years it passed through many vicissitudes, and at intervals the difficulty – not uncommon with village free churches in those days – was experienced of prosecuting the end for which the chapel was erected with any degree of success. Financial hamperings, meagre congregations, and other hinderances stood in the way of immediate progress, Dogged determination, however, subsequently removed these difficulties, and of late the work has steadily but continuously gone ahead, until at the present time the chapel is one of the most successfully conducted in the Newport Pagnell district. Some six years ago it was found that in order to bring the building up to date, considerable interior alterations would have to be made, and the more ardent workers in the cause bestirred themselves with a view to bringing about this much desired end. Although their endeavours to raise the necessary funds were in a degree successful, the putting of the work in hand was delayed until about a couple of months ago. The interior walls have been distempered a pale green, with a stencil in a darker shade, and the ceiling whitened. The pine wainscoting has been considerably heightened, and the wall seats used for so many years have been removed. Here it may be mentioned that that it is in the seating arrangements the greatest improvement has been effected. Low pine seats displace the open-backed forms which formerly did service the chapel, and these are so places as to make an aisle up the centre of the building. Two additional lamps have also been provided, and the windows have been glazed in larger panes, the ornamented glass introduced adding to the effect of the improved lighting. The entrance, porch, the materials and labour for which has been paid for by friends of the chapel, has removed the old lobby, and made the means of entry much more convenient. The total cost of the work was about £45. Mrs. E. Wright, painter and decorator, of Newport Pagnell, carried out the work of renovation to the satisfaction of all concerned, and the new seats were made by Mr. H. Rose, builder, also of Newport Pagnell.

Resisting dissent

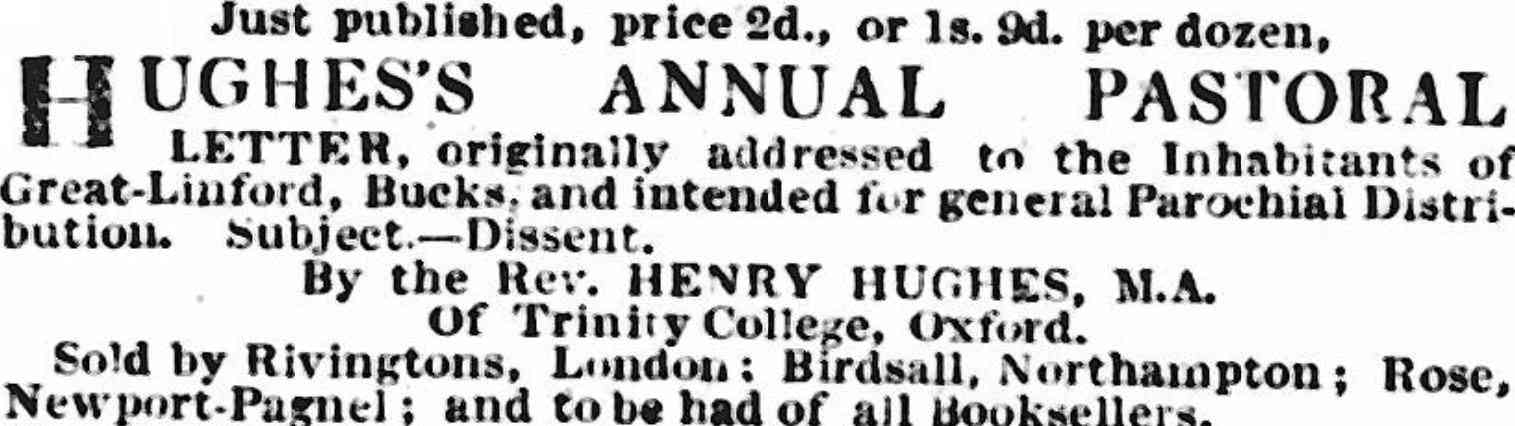

The somewhat cryptic reference to difficulties, “not uncommon with village free churches in those days” very likely has to do with resistance from the established church and the pressures they could bring to bear upon wavering parishioners, of which we have a perfect example to hand for Great Linford. Henry Hughes was the Curate of Great Linford at the time of the founding of the Congregational Chapel, and in early 1834 we find the following advertisement widely publicised in newspapers.

So here have an annual pastoral letter to the inhabitants of Great Linford, which from the tone of advertisement seems squarely aimed at those who might be considering attending the new Congregational Chapel, and this is indeed the case, as the document luckily survives. You can download the full Pastoral Letter of the Reverend Henry Hughes here, but to pick out one choice passage:

The fact is, that most of those who would win you over to forsake the communion of a church in whose privileges your forefathers rejoiced, would do it for their own sakes and not for yours, they would do it to answer their own ends and purposes and not to promote the salvation of your souls; and it is also a fact that if you are prevailed upon to separate, even partially, from her for any other reason but because you are convinced that her doctrines are corrupt and unscriptural, you are led to commit a grievous sin and one for which you will have to answer to God.

George Osbourn

As to George Osbourn whose largesse allowed the building of the Chapel in 1833, the 1840 Tithe Map for Great Linford lists him as owning property and land in several locations within the village, including what would become known as Chapel Yard, but he was not a resident of Great Linford, rather making his home in Newport Pagnell. A will for a George Osbourne of Newport Pagnell proved in 1857 describes him as a Woolstapler, meaning he was a dealer in sheep’s wool. From census records we can pinpoint his age and from a baptism record, a date of birth, October 7th, 1776 at Newport Pagnell. His religion affiliation seems obvious, but other than the newspaper account of 1906, we have nothing more to understand his motivation in donating the land. Interestingly, his will was witnessed by a W. R. Bull, a surname synonymous with the Congregationalist movement in the town.

Indeed, it is Josiah Bull, who in 1851 filled in the details for Great Linford’s Chapel on the 1851 census of places of religious worship. This is a useful document, as it provides a snapshot of how many people attended Chapel on March 30th, 1851, hence we know there were 81 in attendance that Sunday evening, out of a parish population of 486.

Indeed, it is Josiah Bull, who in 1851 filled in the details for Great Linford’s Chapel on the 1851 census of places of religious worship. This is a useful document, as it provides a snapshot of how many people attended Chapel on March 30th, 1851, hence we know there were 81 in attendance that Sunday evening, out of a parish population of 486.

Schooling at the Congregational Chapel

Though the evidence is scant for its scope and duration, it seems that in the early 1860s at least, there was some effort under way to provide not just the typical Sunday School provision expected of any Church, but some day schooling as well. This would have been then in competition with the schooling provided by Pritchard’s Charity (though by then part of the Church of England National Schools system), and may have been another source of friction between the two competing faiths. The only evidence for this endeavour comes from a story in Croydon’s Weekly Standard Newspaper of August 9th, 1862, which makes reference to the annual school feast paid for by Mr and Mrs Garratt of Ivy House for upwards of 60 children of the “Independent chapel Sunday and day schools.”

A further note concerning schooling at the Independent Chapel was reported in June of 1871, but though much satisfaction was expressed as to the success of the Sunday School, there is no mention of a day school, so perhaps this was a brief experiment, plus of course St. Andrew’s School was to open on the High Street just a few years later in 1875.

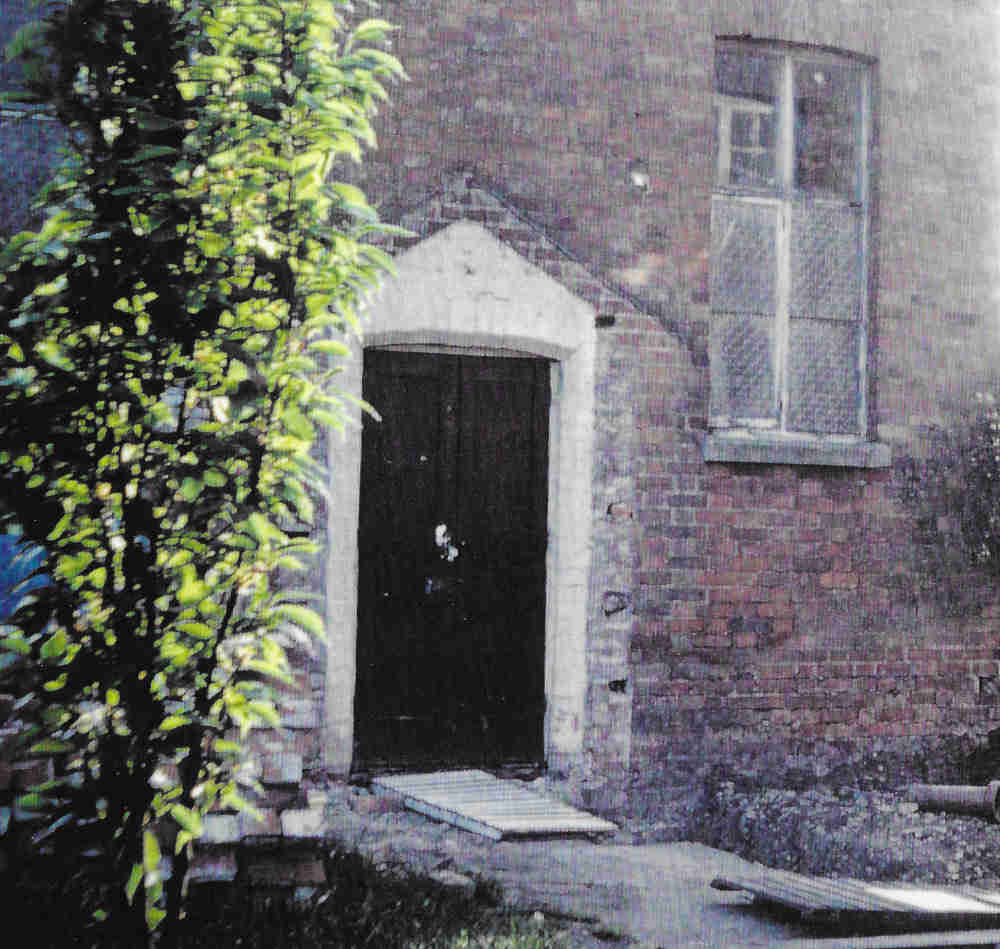

It is not clear when the Congregational Hall closed for worship and was converted into a house, but the exterior fabric of the building retains its original character, and with its prominent date stone atop the wall, can still be seen from the High Street.

A further note concerning schooling at the Independent Chapel was reported in June of 1871, but though much satisfaction was expressed as to the success of the Sunday School, there is no mention of a day school, so perhaps this was a brief experiment, plus of course St. Andrew’s School was to open on the High Street just a few years later in 1875.

It is not clear when the Congregational Hall closed for worship and was converted into a house, but the exterior fabric of the building retains its original character, and with its prominent date stone atop the wall, can still be seen from the High Street.