A History of Farming in Great Linford

The earliest excavated farmsteads within the modern borders of Milton Keynes have been dated to the Iron Age, circa 500-100BC. There has been academic debate that the Romans repurposed some of these settlements for their own use, such as at Stanton Low, close to Great Linford, where an Iron Age structure appears to predate a Roman building raised in its stead, but what exactly was occurring in the vicinity of Great Linford at this time is largely a matter of conjecture. Things do not become any more certain with the departure of the Romans circa 410AD. However, a particularly complete example of a Saxon settlement (6/7th century) was discovered at Pennyland, which given its relative proximity (approximately a mile to the south-east) has raised speculation that it might have been a precursor of sorts to the medieval village of Great Linford.

In the medieval period, individuals were allocated strips of arable land that they could cultivate called furlongs. The use of oxen drawn ploughs gave rise to a distinctive “ridge and furrow” landscape, though next to nothing of these now remain around Great Linford. Notably, the settlement at Pennyland was found to lie below ridge and furrow, inferring that the furlongs in the vicinity of Great Linford were also established no earlier than the 7th century.

Maynard and Zeepvat (Monograph Series number 3, 1992) date the founding of the village to the tenth or eleventh centuries, with a so-called field system likely established at much the same time. A manor (an administrative area with a lord and his subjects) would typically have two or three of large (or great) fields, with crops rotated each year and one left fallow. Great Linford initially had two fields, named in a 1449 document as Segelowfeld and Le Dounefeld; the former takes its name from Secklow Mound, the Saxon era meeting place for the Seklow Hundred (an administrative area), while the latter can be interpreted as meaning Lower field. By at least the early 17th century, the parish had adopted a three-field system, identified by Maynard and Zeepvat as Wood Field, Newport Field and Middle Field.

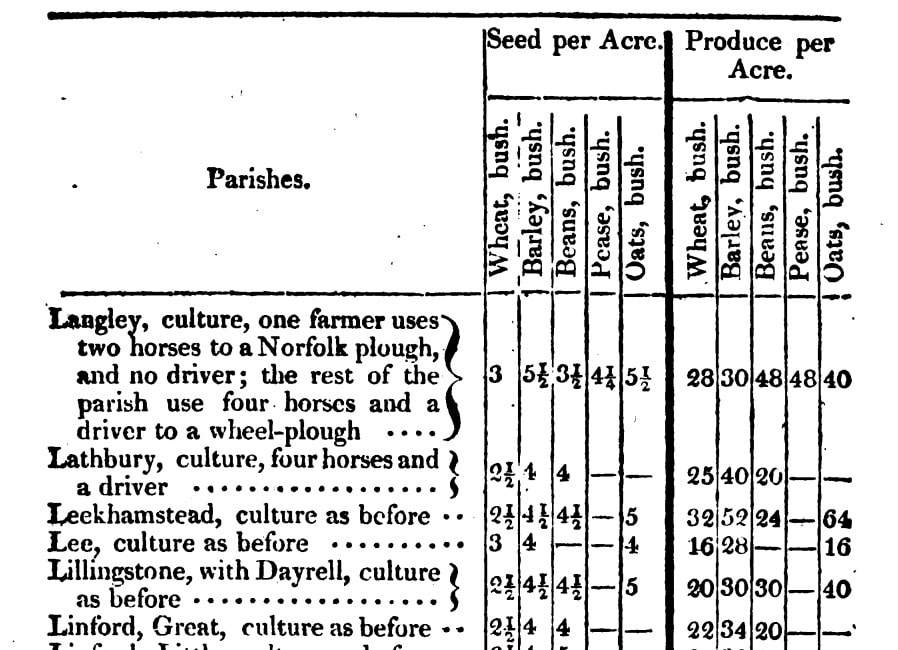

Villages (known in antiquity as Vills) were the predominant type of settlement in medieval times, run under the manor system, with the fields set around each village providing the inhabitants with staple foodstuffs. The crops grown on arable land would have been cereals like wheat, barley and oats, alongside peas and beans. Vegetables such as parsnips, cabbages and carrots would have been grown in the cottage gardens of crofts, of which a number have been discovered and excavated within the village.

In the medieval period, individuals were allocated strips of arable land that they could cultivate called furlongs. The use of oxen drawn ploughs gave rise to a distinctive “ridge and furrow” landscape, though next to nothing of these now remain around Great Linford. Notably, the settlement at Pennyland was found to lie below ridge and furrow, inferring that the furlongs in the vicinity of Great Linford were also established no earlier than the 7th century.

Maynard and Zeepvat (Monograph Series number 3, 1992) date the founding of the village to the tenth or eleventh centuries, with a so-called field system likely established at much the same time. A manor (an administrative area with a lord and his subjects) would typically have two or three of large (or great) fields, with crops rotated each year and one left fallow. Great Linford initially had two fields, named in a 1449 document as Segelowfeld and Le Dounefeld; the former takes its name from Secklow Mound, the Saxon era meeting place for the Seklow Hundred (an administrative area), while the latter can be interpreted as meaning Lower field. By at least the early 17th century, the parish had adopted a three-field system, identified by Maynard and Zeepvat as Wood Field, Newport Field and Middle Field.

Villages (known in antiquity as Vills) were the predominant type of settlement in medieval times, run under the manor system, with the fields set around each village providing the inhabitants with staple foodstuffs. The crops grown on arable land would have been cereals like wheat, barley and oats, alongside peas and beans. Vegetables such as parsnips, cabbages and carrots would have been grown in the cottage gardens of crofts, of which a number have been discovered and excavated within the village.

Domesday

By the time of the arrival of the Normans in 1066, the well-established field system would have likely continued uninterrupted; only the upper echelons of Saxon society would have been severely disrupted, with new Norman lords appointed. The Domesday book of 1086, commissioned by William the Conqueror provides some detail on the organisation of the farmland at Great Linford, though the units of measure require some explanation. Take for instance the lands of Walter Giffard. This had five ploughlands, which was the amount of land that could be ploughed by an eight-oxen plough team in a year. Walter had one lord’s plough, a team of eight oxen that he owned, and there were additionally four men’s plough teams. Further to this was a meadow measuring four ploughs. The annual worth of Walter’s holdings was judged to be £3 in 1086. It is also worth noting that in total, there were 16 villagers who owed fealty to Walter, plus two smallholders and four slaves. A smallholder might hold in the region of five acres and also have a share in the village plough teams.

Exactly what in modern terms a ploughland can be equated to is a matter of debate, but G.K. Tull, writing in the Journal of the Wolverton and District Archaeological Society (number 2, 1969), settles on a figure of 120 acres per ploughland, and provides a table breaking down the Domesday data for Great Linford. He arrives at 1,110 acres of ploughland and 112 acres of meadowland, giving a total figure of 1,222 acres.

Exactly what in modern terms a ploughland can be equated to is a matter of debate, but G.K. Tull, writing in the Journal of the Wolverton and District Archaeological Society (number 2, 1969), settles on a figure of 120 acres per ploughland, and provides a table breaking down the Domesday data for Great Linford. He arrives at 1,110 acres of ploughland and 112 acres of meadowland, giving a total figure of 1,222 acres.

Enclosure

Enclosure, the process by which common and waste land was fenced (or ditched) off, often by local landowners seeking to maximise profit from the land, had been a growing trend since the 13th century, but things accelerated in the 15th century as the demand for sheep’s wool increased, requiring large fields to contain the flocks. The impact on ordinary agricultural labourers and their families could be calamitous, with villagers even turned out of their cottages, which were then allowed to fall into disrepair and ruin. North Buckinghamshire, with clay soils eminently suitable for conversion to pasture was particularly badly impacted, but enclosure could sometimes occur with the general consent of most involved, and this appears to have been the rare case with Great Linford.

The enclosure was instigated by Sir Richard Napier (the Lord of the Manor) and formally enacted in 1658, the records of which survive at Buckinghamshire Archives (D-U/1/48.) The reason for the relatively uncommon lack of enmity between the parties is perhaps made clear in the surviving record of the agreement, which states, “a great part of the land lies open and unenclosed and commonable. Many spoils, trespasses and destructions occur daily by reason of the escape of cattle into the corn and grass, causing disputes, actions, quarrels and troubles between neighbour and neighbour.”

With the enclosure agreed in principle, a surveyor was appointed to mark out each person’s land, “as near adjoining to their dwellings as with conveniency may be”, and referees were appointed who would decide on fencing and compensation. All told, it does seem as reasonable and fair a process as could be imagined at the time, though it is not recorded if anyone did object. Surely some did, and perhaps tellingly, it does appear that in the aftermath of enclosure the population declined.

The enclosure had certainly vastly changed the character of the parish. Writing in the Agricultural History Review (Enclosure in North Buckinghamshire, 1500-1750, Vol 32, 1884, part 1) Michael Reed provides an evocative picture of the changes wrought upon the landscape by enclosure. “Great Linford was transformed. New hedges, ditches and roads appeared. A new pattern of closes replaced the old open fields. A landscape emerged that must have been both neater and greener than that which it replaced.”

Further supporting this, Reed cites two glebe terriers, documents routinely drawn up to survey lands in the ownership of the church. A pre enclosure 1607 glebe terrier describes the church’s land in the parish as being scattered across 34 distinct plots, but by 1690, this has coalesced into 28 acres of enclosed land in four closes adjoining the parsonage orchard. But the very nature of farming had also been upended, as Reed demonstrates from his analysis of an estate rent book entry dated Lady Day, 1714. Lady Day traditionally fell on March 25th, and celebrates the Feast of the Annunciation, but it also marks the first of the four quarters in the year that rents came due. Reed draws an insightful conclusion from the rent book, that of eleven “farms” referenced, only three had small amounts of ploughed land, from which it can be inferred that the enclosure had effectively turned almost the entire parish to pasture.

The enclosure was instigated by Sir Richard Napier (the Lord of the Manor) and formally enacted in 1658, the records of which survive at Buckinghamshire Archives (D-U/1/48.) The reason for the relatively uncommon lack of enmity between the parties is perhaps made clear in the surviving record of the agreement, which states, “a great part of the land lies open and unenclosed and commonable. Many spoils, trespasses and destructions occur daily by reason of the escape of cattle into the corn and grass, causing disputes, actions, quarrels and troubles between neighbour and neighbour.”

With the enclosure agreed in principle, a surveyor was appointed to mark out each person’s land, “as near adjoining to their dwellings as with conveniency may be”, and referees were appointed who would decide on fencing and compensation. All told, it does seem as reasonable and fair a process as could be imagined at the time, though it is not recorded if anyone did object. Surely some did, and perhaps tellingly, it does appear that in the aftermath of enclosure the population declined.

The enclosure had certainly vastly changed the character of the parish. Writing in the Agricultural History Review (Enclosure in North Buckinghamshire, 1500-1750, Vol 32, 1884, part 1) Michael Reed provides an evocative picture of the changes wrought upon the landscape by enclosure. “Great Linford was transformed. New hedges, ditches and roads appeared. A new pattern of closes replaced the old open fields. A landscape emerged that must have been both neater and greener than that which it replaced.”

Further supporting this, Reed cites two glebe terriers, documents routinely drawn up to survey lands in the ownership of the church. A pre enclosure 1607 glebe terrier describes the church’s land in the parish as being scattered across 34 distinct plots, but by 1690, this has coalesced into 28 acres of enclosed land in four closes adjoining the parsonage orchard. But the very nature of farming had also been upended, as Reed demonstrates from his analysis of an estate rent book entry dated Lady Day, 1714. Lady Day traditionally fell on March 25th, and celebrates the Feast of the Annunciation, but it also marks the first of the four quarters in the year that rents came due. Reed draws an insightful conclusion from the rent book, that of eleven “farms” referenced, only three had small amounts of ploughed land, from which it can be inferred that the enclosure had effectively turned almost the entire parish to pasture.

Landowners

It is important to distinguish between landowners and tenants. Historically, the farmland of Great Linford was almost, if not entirely, in the ownership of the Lords of the Manor (or others from the upper strata of society), a state of affairs that continued well into the 20th century. Writing in her treatise on The Impact of a mid-seventeenth century enclosure on a North Buckinghamshire village, Elizabeth Sainsbury (Milton Keynes Archaeology Unit, Parish Survey, Part 1) identifies two principal estates in the parish prior to enclosure, which she estimates to have encompassed at least 50-55% of the total available acreage.

The principal estate was owned from 1560 by the Thompson family of Husborne Crawley, with an estimated 780 acres split into three large farms and a number of smaller parcels. The other estate was known as Pipard’s or Walshe’s manor and had been obtained by the Tyringham family (of Tyringham) in 1571. Their estate included a capital messuage, meaning the chief house (or farmstead), plus one other messuage, three cottages and 138 acres of land, plus commons and meadows. Sainsbury describes both the Thompsons and Tyringhams as “absentee landlords”, and offers up several other examples, a Thomas Longville of Bradwell who held 60 acres of Linford Wood and the trustees of the almshouses at Shenley, who held land measuring 75 acres. This latter example is land that can be associated with Windmill Hill Farm.

A prenuptial agreement between Sir Richard Napier (1607-1676) and Mary Kynaston dated 1649 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/2) confirms the continued existence of the two manors and provides an account of not only the lands held, but the messuages therein, and even the numbers of livestock supported. The document tells us that the Manor House (this being the medieval house that now lies below the Arts Centre carpark) came with 222 acres of arable land, plus meadow lands and a variety of other plots, the grand total coming to some 320 acres. The document further details that the common land called the Layfield had capacity for 300 sheep and 24 cattle. Walshes Manor had some 118 acres with common land for 160 sheep, 14 cows, 14 dry beasts and 8 horses. The reference to dry beasts is a term used to describe that part of an adult herd not being milked as they are waiting to give birth to their next calf. The agreement also lists various other messuages and lands, totalling 531 acres.

Though they would have derived a lot of their income from rents, it does not seem remotely implausible to imagine that the landed gentry were undertaking some farming on their own account. The prenuptial agreement mentions no tenants for the two manors, and though this is not to say they did not exist, there is certainly evidence to the effect that Napier had his own lifestock. Carried in an account from 1669 of a criminal case heard before the Bedfordshire Winter Assize, we learn that Napier was grazing a flock of “threescore sheepe” in a paddock at Leighton Buzzard (explaining why the case was heard at the Bedfordshire Assizes) when one of them was stolen. A search of the suspects home found a sheep skin secreted in the rafters, which bore the brand R N, sealing the thief’s fate.

Another important landholder was the church, which extracted an income from so-called Glebe land that was given over to the use of the parish’s Rector; an echo of this arrangement is to be found on the High Street in the form of Glebe House. The Glebe land extended back behind this house. The Rector also obtained money from tithes. Tithes were a tax set at 10% of a person’s harvest. It seems reasonable to suppose that there was a tithe barn somewhere in the parish where this produce was taken to and stored, but no evidence has yet come to light to pinpoint its location.

During the enclosure process, the bishop of Lincoln held a visitation at Stony Stratford in July 1662, where he gave his blessing to the Great Linford enclosure, having confirmed to his satisfaction that the 28 acres that had been marked out as the rectory’s new glebe land was of better quality than the original allocation. Also, since it was closer to the rectory house, it was judged more convenient, commodious and profitable to the incumbent. That glebe land can still be seen marked out in the tithe map produced in 1840 (Buckinghamshire Archives, Tithe/255), when it was decided to switch to monetary payments rather than agricultural produce.

The 1840 tithe map gives a tally of 1,595 acres in the hands of the Uthwatts. Only 192 acres of farmland are in the hands of other landowners, and one of those, Harriet Knapp (with 81 acres of what became known as Windmill Hill Farm), was related by marriage to the Uthwatts. Things have little changed by 1910, when another map was created for tax gathering purposes. At this time, the Uthwatts are in possession of 1,620 acres (having acquired Windmill Hill Farm from the Knapps) and it is not until the 1960s that we seem some evidence that the Lords of the Manor are beginning to disinvest themselves of their holdings in the parish.

The principal estate was owned from 1560 by the Thompson family of Husborne Crawley, with an estimated 780 acres split into three large farms and a number of smaller parcels. The other estate was known as Pipard’s or Walshe’s manor and had been obtained by the Tyringham family (of Tyringham) in 1571. Their estate included a capital messuage, meaning the chief house (or farmstead), plus one other messuage, three cottages and 138 acres of land, plus commons and meadows. Sainsbury describes both the Thompsons and Tyringhams as “absentee landlords”, and offers up several other examples, a Thomas Longville of Bradwell who held 60 acres of Linford Wood and the trustees of the almshouses at Shenley, who held land measuring 75 acres. This latter example is land that can be associated with Windmill Hill Farm.

A prenuptial agreement between Sir Richard Napier (1607-1676) and Mary Kynaston dated 1649 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/2) confirms the continued existence of the two manors and provides an account of not only the lands held, but the messuages therein, and even the numbers of livestock supported. The document tells us that the Manor House (this being the medieval house that now lies below the Arts Centre carpark) came with 222 acres of arable land, plus meadow lands and a variety of other plots, the grand total coming to some 320 acres. The document further details that the common land called the Layfield had capacity for 300 sheep and 24 cattle. Walshes Manor had some 118 acres with common land for 160 sheep, 14 cows, 14 dry beasts and 8 horses. The reference to dry beasts is a term used to describe that part of an adult herd not being milked as they are waiting to give birth to their next calf. The agreement also lists various other messuages and lands, totalling 531 acres.

Though they would have derived a lot of their income from rents, it does not seem remotely implausible to imagine that the landed gentry were undertaking some farming on their own account. The prenuptial agreement mentions no tenants for the two manors, and though this is not to say they did not exist, there is certainly evidence to the effect that Napier had his own lifestock. Carried in an account from 1669 of a criminal case heard before the Bedfordshire Winter Assize, we learn that Napier was grazing a flock of “threescore sheepe” in a paddock at Leighton Buzzard (explaining why the case was heard at the Bedfordshire Assizes) when one of them was stolen. A search of the suspects home found a sheep skin secreted in the rafters, which bore the brand R N, sealing the thief’s fate.

Another important landholder was the church, which extracted an income from so-called Glebe land that was given over to the use of the parish’s Rector; an echo of this arrangement is to be found on the High Street in the form of Glebe House. The Glebe land extended back behind this house. The Rector also obtained money from tithes. Tithes were a tax set at 10% of a person’s harvest. It seems reasonable to suppose that there was a tithe barn somewhere in the parish where this produce was taken to and stored, but no evidence has yet come to light to pinpoint its location.

During the enclosure process, the bishop of Lincoln held a visitation at Stony Stratford in July 1662, where he gave his blessing to the Great Linford enclosure, having confirmed to his satisfaction that the 28 acres that had been marked out as the rectory’s new glebe land was of better quality than the original allocation. Also, since it was closer to the rectory house, it was judged more convenient, commodious and profitable to the incumbent. That glebe land can still be seen marked out in the tithe map produced in 1840 (Buckinghamshire Archives, Tithe/255), when it was decided to switch to monetary payments rather than agricultural produce.

The 1840 tithe map gives a tally of 1,595 acres in the hands of the Uthwatts. Only 192 acres of farmland are in the hands of other landowners, and one of those, Harriet Knapp (with 81 acres of what became known as Windmill Hill Farm), was related by marriage to the Uthwatts. Things have little changed by 1910, when another map was created for tax gathering purposes. At this time, the Uthwatts are in possession of 1,620 acres (having acquired Windmill Hill Farm from the Knapps) and it is not until the 1960s that we seem some evidence that the Lords of the Manor are beginning to disinvest themselves of their holdings in the parish.

Tenants

As previously noted, the farmland in the parish of Great Linford was owned since time immemorial by wealthy landowners, who could then rent out parcels of land to tenant farmers. Though there was also common land and meadows that residents had access to, Elizabeth Sainsbury notes that the main estate held by the Thompsons had been split into three large farms and a number of smaller parcels, while the smaller estate held by the Tyringham family was split between one large tenancy and three smaller holdings. Sainsbury notes a number of other landholders circa 1640 who were resident in Great Linford; with four “farmers” identified as Thomas Nicholls (89 acres), Ralph Smith (120 acres), Richard Wethered (80 acres) and Willian Gaddesden (30 acres.)

There were strict regulations as regards the use of land, such as how many head of lifestock could be be grazed, with fines for infractions. This necessitated a complex system of codified rules, as Sainsbury notes from the following passage, drawn from a Court Baron (a manorial court) convened in 1630. (Buckinghamshire Archives D/U/2/6.)

There were strict regulations as regards the use of land, such as how many head of lifestock could be be grazed, with fines for infractions. This necessitated a complex system of codified rules, as Sainsbury notes from the following passage, drawn from a Court Baron (a manorial court) convened in 1630. (Buckinghamshire Archives D/U/2/6.)

No inhabitant, except the 2 great farms shall, after November 11th, keep above 36 sheep for one yardland and so after that rate for more or less land, and (that) any lamb bred in the fields shall be accounted for a sheep at Martinmas.

A yardland is an archaic term for a unit of land, between 15 and 40 acres depending on the locality, while Martinmas is St. Martin’s Day, celebrated on November 11th.

Another example of the very precise rules that could be laid down is to be found in a deed of 1652-1654 relating to the purchase of land by Sir Richard Napier (Buckinghamshire Archives D/U/1/43.) This specifies the specific entitlements of a Thomas Kent.

Another example of the very precise rules that could be laid down is to be found in a deed of 1652-1654 relating to the purchase of land by Sir Richard Napier (Buckinghamshire Archives D/U/1/43.) This specifies the specific entitlements of a Thomas Kent.

Seven half yards of meadow in the meadows of Great Linford as they arise yearly by lot, one swath of meadow every other year cut of the meadows of Sir Richard Napier in the tenure of Roger Kings, and one pole of meadow every other year cut of the meadow ground late George Peirson.

The parish burial records of St. Andrew’s church provide us the names of rich and poor alike, and according to the inclinations of the resident parish priest, sometimes offer more than just the bare details of the date of interment, but also the occupation of the deceased, or sometimes if a wife or child, the occupation of the husband or father. John Coles, who became Rector in 1699, was a particularly meticulous clerk in this regard, though the records he carefully compiled during his tenure (which lasted until 1748) raise an interesting ambiguity.

His parish burial entries record a grazier, a pasturekeeper and numerous dairymen, but not once does he record the death of a “farmer.” This pattern continues with his successors in office, and it is not until the tenure of the Reverend Edmund Smyth, who arrived in 1770, that the word farmer is used as a profession. To try and understand this, it is helpful to look briefly at the origins of the word farm, which comes from the Anglo-French 'fermer', meaning "to rent.” The French verb is based in turn upon the Medieval Latin firma, meaning "fixed payment," and the Latin verb firmare, "to make firm." A “farmer” in medieval times was in essence then a debt collector, but the Merriam-Webster dictionary tells us that the words farm and farmer, as purely agricultural terms, began to enter into the lexicon at the beginning of the 16th century, and by the end of that century had attained their common modern meaning.

But in the 18th century, the reverends of Great Linford (or their clerks) were not using the word farmer, preferring Dairyman, which surely must must imply a speciality in the parish for milk production. A dairyman has been defined as a person or family who rented a herd of cows from either a landlord of large tenant. Between 1701 and 1771, we find reference to some two dozen families whose head is described as a dairyman, with the only exceptions being William Cooke, described as a pasturekeeper and Samuel Shilborn, who is described as a grazier. William we can presume was maintaining fields for the grazing of cattle, that he was then perhaps renting out to others, while Samuel as a grazier would have been rearing cattle and/or sheep for market; this does seem to confirm again that the Great Linford estate was heavily skewed at this time toward milk production, though we should not discount the possibility that the prevalence of the tern Dairyman may have be a local idiom or idiosyncrasy of the incumbent rectors and their clerks during this period of time.

The burial records do provide another, rather grim statistic, particularly demonstrated by the example of the Shilborns. In a space of less than two years, Samuel and his wife Elizabeth lost three infant children, Samuel aged eight days in April 1717, followed closely by two-year-old Johnathan a month later, then finally a daughter Mary in 1719, aged seven months.

Referring back to Michael Reed’s analysis of Enclosure in North Buckinghamshire, his examination of the 1714 estate rent book finds that there were 14 tenants in the parish, including a Thomas Shilborn; surely a relation to the aforementioned Samuel Shilborn. Thomas was not however a resident of the parish, but of Great Brickhill. Thomas was in partnership with a Ralph Coleman of Fenny Stratford, the pair paying £110 a year for three-year lease of 203 acres of pasture, divided into three closes; Kents Ground (80 acres), Great Cowpen Meadow (21 acres) and Neath Hill (102 acres).

Reed can identify with any certainty only five farmhouses in the parish, additionally observing that land was leased out to prosperous tenants, several (as previously noted) with no obvious connection with the parish. Reed identifies them as butchers, graziers and dairymen concerned with supplying the London market. An additional source of information is provided by an oath of allegiance to the crown carried out across the country in 1723. The oath was limited to those persons over the age of 18 who held freehold, copyhold or leasehold lands, and provides 19 names in the parish, including the Reverend Coles and his wife Anne, and the then Lord of the Manor, Thomas Uthwatt and his wife Katherine. Other names in this document, whom at present we cannot tie to specific farmsteads, include John Cook, Ann Coles, Philip Gunn and Alice West.

Moving on through time to 1757, a Mortgage by Release (D-BAS/41/178) held by Buckinghamshire Archives presents a few familiar names, as well as several new ones. This agreement between Henry Uthwatt esquire and his wife Frances, plus a John Maire esquire of Grey's Inn in Middlesex and a merchant named James Buchanan of Mark Lane, London, provides details on five farms. Usefully, some of the field names mentioned in this document can be matched to an estate map drawn up in 1641, which in turn can be cross referenced to the tithe map created in 1840. This means that (with various degrees of confidence) we can build up credible histories for a number of farms from 1757 to modern times.

A particularly good example of the connections to be extrapolated from the 1757 mortgage is a messuage in the occupation of George Rawlins, with fields named Herns House Close, First Long Ground, Second Long Ground, Third Long Ground and Nicholas Mead, measuring all together 134 acres, two roods and 34 perches. These measurements are old terminology for the measurement of land; a rood being equal to one quarter of an acre, while a perch was equal to 5½ yards, with 160 square perches equaling an acre.

George Rawlins was very likely the son of a John Rawlins, baptised March 16th, 1706. Following the paper trail onwards from the 1757 mortgage points particularly strongly toward the conclusion that several generations of the Rawlins family were occupying what would come to be known as Grange Farm, though the field name “Herns House Close” offers the intriguing possibility that a person named Hern was previously associated with the property, and indeed there is a Hearne family (note the differing spelling) sporadically recorded in the parish records during the late 1600s.

The next parcel of land is in the occupation of a Thomas Pinkard, who is occupying fields named Wood Close, Great Ground, Stanton Slade, Little Stanton Slade, Newmans Close, The Grove, Upper Meadow, Lower Meadow and The Green, a total of 227 acres, two roods and two perches. The documents refers to this as a farm, though in this case no mention is made of an accompanying messuage. However, the field known as The Great Ground (a field also identified on an estate map of 1678) would one day become the site of the house known as Wood House, also called Wood End Farm.

Turning now to land described as formerly in the occupation of a John Hooton, the 1757 mortgage elaborates that it has subsequently passed into the occupation of Philip Ward. Philip died at Great Linford in January 1784, the parish record of his burial describing him as a dairyman. He held three fields: Morrall Leys; Furness Meadow and Townsend Meadow containing 102 acres, five perches, as close as can be determined, land that would later become associated with The Black Horse Inn. His grandson Phillip Hoddle Ward would do very well for himself, though come to a rather surprising end, as will become clear later in this history. The name Hooten does figure with any regularity in the parish records until the early 1800s, so John Hooton may have been another “absentee landlord.”

A “messuage and farm” in the occupation of Richard Oliver is particularly interesting, as it refers to a “Taylors House and Close”, alongside four fields, the total coming to 131 acres and 25 perches. Taylors House is presently something of a mystery, but we may be able to glean a clue as to its location from the fields associated with this farm. With a combined acreage of 131 acres, 25 perches, these fields were Dryside Brook, Pennyland Field, Ash Leys and Church Lees, all of which can be identified on the 1678 estate map.

Dryside Brook and Pennyland Field were located to the south-east of The Green, while Ash Leys and Church Lees (the latter actually divided into two fields on the 1678 estate map) were on the west side of the High Street. It is these fields, which extended as far as the church, that offer the most promise for divining the location of Taylors House, as one of the Church Lees fields directly abutted that portion of the High Street upon which the present-day Glebe House sits. The house is described in A Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes (1986, Paul Woodfield, Milton Keynes Development Corporation) as of late 17th or early 18th century construction, and a sales notice in 1777, carried in the Northampton Mercury of March 17th, does offer a description of the house that seems a strong match. Conceivably then, Glebe House may once have been known as Taylors House.

Finally on the 1757 mortgage document, we have four closes in the occupation of John Yeomans called: Secklay Hill; Tongwell Mead; Cocket Brook Mead and Fulwell Ground containing together 152 acres, three roods and 10 perches. Cross-referencing to the 1678 estate map, John appears to have been farming land that would later be subsumed into Grange Farm.

Turning back to the burial records for the parish, amongst the “dairymen” recorded we find the names Bacchus, Pavyer, Rawlins and Ward. A Richard Bacchus, who was buried on May 8th, 1778, is also the first person in the parish burial records to be described as a farmer. Unfortunately, he is also the only person thus described, as the records become much less detailed from this time onwards, but significantly, all four of the aforementioned surnames recur in an indenture drawn up in 1808 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X_2228.) The document provides a highly detailed accounting of the distribution of land between the Uthwatts, who had inherited the estate in 1704 and seven of their tenants. Notably, the word “farmhouse” also features prominently in this document, so we can be sure all these men were residing in farmsteads, each with a house and significant parcels of land. Unfortunately, a few of the figures in the indenture have become illegible with the passage of time, but none-the-less we can arrive at a reasonably accurate grand total in the region of 1627 acres.

The indenture contains not only the acreage assigned to each tenant, but the specific field names (where legible) in their tenure, which when combined with the information contained in the 1840 tithe map, allows us to join the dots and with varying degrees of confidence place individual farmers at specific farms in 1808.

One such is Benjamin Pavyer, who was undoubtedly the tenant of Church Farm and James Hawley, who was at the house now known as The Cottage, but others like Anthony Rowland, whose almost 800 acres encompassed broad swathes of land, are much harder to connect with any specific farmstead. Indeed, as we will see, it seems he was not necessarily even permanently resident in the parish, though interestingly the indenture makes mention of a house with a “pleasure garden” in his tenure. This raises the intriguing possibility he was renting the manor house, or perhaps Glebe House on the High Street, with its impressive walled garden.

Frustratingly, for a farmer with such extensive lands, Anthony Rowland left a rather sparse body of evidence as to his comings, goings and doings. Presuming it to be the same person, a will for an Anthony Rowland proved in 1813 describes him as a victualler and coal dealer resident in Bradwell village, with a burial record dated 1812 backing up the place of residence and additionally putting his age at 39. A Grant of annuity by the Pelican Life Insurance Company dated 1812 (with release of annuity, 1815, 1812-1815) held by Buckinghamshire Archives (D-U/1/27) provides some further evidence that all these records relate to the same person, as the document refers to land at Great Linford, and a messuage or farmhouse formerly in the occupation of Anthony Rowland, but now in the occupation of a Luke Alibone. This sounds very much like a transaction carried out after Anthony’s death, which would fit the timeframe of the other documents. Here however the trail goes rather cold.

The Bacchus brothers, William and Richard are a better prospect for study. Cross referencing the field names in the 1808 indenture with the 1840 tithe map allows us to locate the Bacchus brothers with some confidence to Lodge Farm. However, from 1822, Richard Bacchus served as landlord of The Nags Head until his death in 1832, followed by his widow Sarah until 1865.

George Lines was born circa 1773, and though a place of birth has not yet been identified, he did leave a small paper trail of his time at Great Linford, the earliest of which is an 1803 letting agreement with Henry Uthwatt of Great Linford Manor (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/3/27) for a house and land formerly in the occupation of a man named only as Pinkard, but perhaps related to the Thomas Pinkard previously mentioned in connection to the mortgage of 1757. The grant of annuity issued by the Pelican Life Insurance Company makes further reference to George, the acreage being an exact match to the figure provided in the 1808 indenture. George clearly had ambitions, as a mortgage document by Uthwatt to Nelson, King and Hearn for £3,000 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/30) entered into 1820-1825 reveals that George had subsequently acquired several more tenures, all including farmhouses and lands, by which we can presume he may have been subletting.

In addition to his original holdings, George held 128 acres formally in the occupation of William and Richard Bacchus, plus the 199 acres formally held by John Rawlins. Sadly for George, his burgeoning empire was not to be, as he passed away in 1823 at the age of 50, having been predeceased by his wife Martha Lines, nee Shaw, a few years previously. The couple had at least eight children, baptism records at Great Linford having been located for all but one.

The Wards, Sarah and her son Philip Hoddle Ward esquire, represent one of the most intriguing names on the 1808 indenture, Philip having been one of the principal signatories; not surprising as he owned the manor of Tickford Abbey at Newport Pagnell. He had also been appointed sheriff of Buckingham in 1805. We can place the Wards in the parish from a variety of records, but most notably from a run of bad luck that afflicted two generations of the family in the 1770s.

The Northampton Mercury of April 8th, 1771, contains an appeal from John Ward, likely Philip’s father, for information (with a reward offered) concerning the theft of a Bright-Bay Mare from his grounds. This contains an interesting description of the horse, including the quirky identifying detail that it had, “a little knob on the side of her belly, done by a cow when young.”

A few years later it was the turn of Philip’s grandfather, also called Philip, to appeal for help, this time in regard to the theft of two calves. The Northampton Mercury of November 1st, 1773, includes the detail that the crime was perpetrated from a field named Great March, which also appears on the 1840 tithe map for the village, one of a trio of fields owned by the Reverend Richard Courtley and located adjacent to land destined to become the canal wharf. A Reverend Courtley is captured on the 1841 census residing in the parish of St Paul Covent Garden in London, so it appears he had invested in 46 acres of pasture in Great Linford. Philip Ward the elder passed away in 1784. He is described as a dairyman in the parish burial record, so we have evidence for a succession of Wards farming at Great Linford.

Philip Hoddle Ward and his mother are referenced again in the mortgage of 1820-1825, with the same parcel of land in their tenure, but it is what happens to Philip in later years that sets the story apart from others, as he was viciously murdered in Paris in 1844, having fled there after a financial scandal. For the story of the Ward family, click here.

The grant of annuity of 1812-1815 provide s several other names, with a piece of land measuring 77 acres, one rood and 18 perches in the occupation of Abraham Barrett called Great Marsh (north of the canal) and 82 acres, two roods and 35 perches called Little Marsh, in the occupation of a person named only as Brooks. Further research is required on these tenants if we are to pinpoint the land they worked, but it is frustrating that in this period, identifying information is extremely thin on the ground.

Newspaper advertisements for the sale or letting of farms can be equally obtuse, such as the one to be found in the Northampton Mercury of Saturday October 22nd, 1814. The owner is named as Henry Andrewes Uthwatt (of the manor house), but neither farm nor occupier is named. The only identifying information to be gleaned from the advertisement regarding its location is that the land was bisected by the canal, so a possible candidate is Windmill Hill Farm, though this is far from certain.

As we have seen then, connecting specific persons to specific farmsteads is not always possible, and indeed prior to the mid to late 1800s, farms were sporadically if at all named; in fact, with no such thing as postal addresses as we understand them today, even legal documents such as mortgages seldom contain any information that can be used to identify the name and location of a property. It is not until the 1850s that farms become more readily identifiable by name, and indeed, the impression is gained that we have reached a period in the history of the parish when farms and farmers are becoming synonymous with each other, with farmsteads becoming established as landmarks within Great Linford.

The 1861 census for Great Linford provides a useful snapshot of agricultural life in the village, as the enumerators appear to have been under instructions to obtain quite detailed information pertaining to farms. Thus we learn that there are six farmers in the village, with land ranging in size from Richard Barratt's 81 acres to Eli Elkin’s 390 acres. Between them these six farmers employed 26 men and 10 boys, though interestingly there are 87 men in the village described as agricultural labourers.

It is also notable that we have one woman running a farm, 63-year-old widow Sophia Hutchinson, who appears to have inherited the occupation of the farm upon the death of her brother John Hawley. The location of her farm is given only as “Green”, but as we have seen previously, evidence clearly placed him at farmhouse known as The Cottage. Also recorded in the same locality are two other farms, one occupied by Eli Elkins, whom we know to have been at Grange Farm on Harper’s Lane, and another by John Clode, who is to be found on the 1840 tithe map at Great Linford House, a now long-lost farmstead on land now occupied by Church Farm Crescent.

Farmers could become relatively well-to-do and can often be seen to be significant and important figures within the community, certainly a step above the average man or woman in the street. John Clode for instance styled himself as an esquire and is described as a gentleman in his will. It is not unusual to find further evidence of their standing locally, such as the frequent appointment of farmers to the board of guardians, responsible for allocating aid to the poor, and jury duty, appointments to which it must be acknowledged, were based on income, rather than any inferred acumen.

However, despite all this, most were still tenants at the whim and mercy of the landholders and could be moved or removed, with the law firmly against the farmer. For example, under a so called “distress for rent” sale, a landlord could seek to recover overdue rent, several cases of which can be found in newspaper accounts. Richard Bacchus was one such unfortunate, with a sale under a distress for rent advertised in the Northampton Mercury of November 30th, 1816, including a rick of capital old beans, two acres of excellent turnips and several ploughs. Benjamin Pavyer found himself in similar straits in November 1829, the Northampton Mercury of the 14th reporting a variety of livestock offered for sale, but also Benjamin’s household furniture, including a four-post bed and bedsteads!

The landlords are not named in these cases, but we can presume that it would have been the Uthwatts. Happily, the Bacchuss family seem to have survived their brush with penury, as the family are heavily associated with The Nags Head public house, and a Benjamin Pavyer is known to have become the village schoolmaster, so we can presume he too got back on his feet.

There was even a farmer who rented the manor house, Edward Slade, whose wife Ann had set up a private girl's school in the house between circa 1878 and 1883. Edward was recorded on the 1881 census as a farmer of 14 acres employing one boy presumably supplementing the income the couple received from school fees.

His parish burial entries record a grazier, a pasturekeeper and numerous dairymen, but not once does he record the death of a “farmer.” This pattern continues with his successors in office, and it is not until the tenure of the Reverend Edmund Smyth, who arrived in 1770, that the word farmer is used as a profession. To try and understand this, it is helpful to look briefly at the origins of the word farm, which comes from the Anglo-French 'fermer', meaning "to rent.” The French verb is based in turn upon the Medieval Latin firma, meaning "fixed payment," and the Latin verb firmare, "to make firm." A “farmer” in medieval times was in essence then a debt collector, but the Merriam-Webster dictionary tells us that the words farm and farmer, as purely agricultural terms, began to enter into the lexicon at the beginning of the 16th century, and by the end of that century had attained their common modern meaning.

But in the 18th century, the reverends of Great Linford (or their clerks) were not using the word farmer, preferring Dairyman, which surely must must imply a speciality in the parish for milk production. A dairyman has been defined as a person or family who rented a herd of cows from either a landlord of large tenant. Between 1701 and 1771, we find reference to some two dozen families whose head is described as a dairyman, with the only exceptions being William Cooke, described as a pasturekeeper and Samuel Shilborn, who is described as a grazier. William we can presume was maintaining fields for the grazing of cattle, that he was then perhaps renting out to others, while Samuel as a grazier would have been rearing cattle and/or sheep for market; this does seem to confirm again that the Great Linford estate was heavily skewed at this time toward milk production, though we should not discount the possibility that the prevalence of the tern Dairyman may have be a local idiom or idiosyncrasy of the incumbent rectors and their clerks during this period of time.

The burial records do provide another, rather grim statistic, particularly demonstrated by the example of the Shilborns. In a space of less than two years, Samuel and his wife Elizabeth lost three infant children, Samuel aged eight days in April 1717, followed closely by two-year-old Johnathan a month later, then finally a daughter Mary in 1719, aged seven months.

Referring back to Michael Reed’s analysis of Enclosure in North Buckinghamshire, his examination of the 1714 estate rent book finds that there were 14 tenants in the parish, including a Thomas Shilborn; surely a relation to the aforementioned Samuel Shilborn. Thomas was not however a resident of the parish, but of Great Brickhill. Thomas was in partnership with a Ralph Coleman of Fenny Stratford, the pair paying £110 a year for three-year lease of 203 acres of pasture, divided into three closes; Kents Ground (80 acres), Great Cowpen Meadow (21 acres) and Neath Hill (102 acres).

Reed can identify with any certainty only five farmhouses in the parish, additionally observing that land was leased out to prosperous tenants, several (as previously noted) with no obvious connection with the parish. Reed identifies them as butchers, graziers and dairymen concerned with supplying the London market. An additional source of information is provided by an oath of allegiance to the crown carried out across the country in 1723. The oath was limited to those persons over the age of 18 who held freehold, copyhold or leasehold lands, and provides 19 names in the parish, including the Reverend Coles and his wife Anne, and the then Lord of the Manor, Thomas Uthwatt and his wife Katherine. Other names in this document, whom at present we cannot tie to specific farmsteads, include John Cook, Ann Coles, Philip Gunn and Alice West.

Moving on through time to 1757, a Mortgage by Release (D-BAS/41/178) held by Buckinghamshire Archives presents a few familiar names, as well as several new ones. This agreement between Henry Uthwatt esquire and his wife Frances, plus a John Maire esquire of Grey's Inn in Middlesex and a merchant named James Buchanan of Mark Lane, London, provides details on five farms. Usefully, some of the field names mentioned in this document can be matched to an estate map drawn up in 1641, which in turn can be cross referenced to the tithe map created in 1840. This means that (with various degrees of confidence) we can build up credible histories for a number of farms from 1757 to modern times.

A particularly good example of the connections to be extrapolated from the 1757 mortgage is a messuage in the occupation of George Rawlins, with fields named Herns House Close, First Long Ground, Second Long Ground, Third Long Ground and Nicholas Mead, measuring all together 134 acres, two roods and 34 perches. These measurements are old terminology for the measurement of land; a rood being equal to one quarter of an acre, while a perch was equal to 5½ yards, with 160 square perches equaling an acre.

George Rawlins was very likely the son of a John Rawlins, baptised March 16th, 1706. Following the paper trail onwards from the 1757 mortgage points particularly strongly toward the conclusion that several generations of the Rawlins family were occupying what would come to be known as Grange Farm, though the field name “Herns House Close” offers the intriguing possibility that a person named Hern was previously associated with the property, and indeed there is a Hearne family (note the differing spelling) sporadically recorded in the parish records during the late 1600s.

The next parcel of land is in the occupation of a Thomas Pinkard, who is occupying fields named Wood Close, Great Ground, Stanton Slade, Little Stanton Slade, Newmans Close, The Grove, Upper Meadow, Lower Meadow and The Green, a total of 227 acres, two roods and two perches. The documents refers to this as a farm, though in this case no mention is made of an accompanying messuage. However, the field known as The Great Ground (a field also identified on an estate map of 1678) would one day become the site of the house known as Wood House, also called Wood End Farm.

Turning now to land described as formerly in the occupation of a John Hooton, the 1757 mortgage elaborates that it has subsequently passed into the occupation of Philip Ward. Philip died at Great Linford in January 1784, the parish record of his burial describing him as a dairyman. He held three fields: Morrall Leys; Furness Meadow and Townsend Meadow containing 102 acres, five perches, as close as can be determined, land that would later become associated with The Black Horse Inn. His grandson Phillip Hoddle Ward would do very well for himself, though come to a rather surprising end, as will become clear later in this history. The name Hooten does figure with any regularity in the parish records until the early 1800s, so John Hooton may have been another “absentee landlord.”

A “messuage and farm” in the occupation of Richard Oliver is particularly interesting, as it refers to a “Taylors House and Close”, alongside four fields, the total coming to 131 acres and 25 perches. Taylors House is presently something of a mystery, but we may be able to glean a clue as to its location from the fields associated with this farm. With a combined acreage of 131 acres, 25 perches, these fields were Dryside Brook, Pennyland Field, Ash Leys and Church Lees, all of which can be identified on the 1678 estate map.

Dryside Brook and Pennyland Field were located to the south-east of The Green, while Ash Leys and Church Lees (the latter actually divided into two fields on the 1678 estate map) were on the west side of the High Street. It is these fields, which extended as far as the church, that offer the most promise for divining the location of Taylors House, as one of the Church Lees fields directly abutted that portion of the High Street upon which the present-day Glebe House sits. The house is described in A Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes (1986, Paul Woodfield, Milton Keynes Development Corporation) as of late 17th or early 18th century construction, and a sales notice in 1777, carried in the Northampton Mercury of March 17th, does offer a description of the house that seems a strong match. Conceivably then, Glebe House may once have been known as Taylors House.

Finally on the 1757 mortgage document, we have four closes in the occupation of John Yeomans called: Secklay Hill; Tongwell Mead; Cocket Brook Mead and Fulwell Ground containing together 152 acres, three roods and 10 perches. Cross-referencing to the 1678 estate map, John appears to have been farming land that would later be subsumed into Grange Farm.

Turning back to the burial records for the parish, amongst the “dairymen” recorded we find the names Bacchus, Pavyer, Rawlins and Ward. A Richard Bacchus, who was buried on May 8th, 1778, is also the first person in the parish burial records to be described as a farmer. Unfortunately, he is also the only person thus described, as the records become much less detailed from this time onwards, but significantly, all four of the aforementioned surnames recur in an indenture drawn up in 1808 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X_2228.) The document provides a highly detailed accounting of the distribution of land between the Uthwatts, who had inherited the estate in 1704 and seven of their tenants. Notably, the word “farmhouse” also features prominently in this document, so we can be sure all these men were residing in farmsteads, each with a house and significant parcels of land. Unfortunately, a few of the figures in the indenture have become illegible with the passage of time, but none-the-less we can arrive at a reasonably accurate grand total in the region of 1627 acres.

The indenture contains not only the acreage assigned to each tenant, but the specific field names (where legible) in their tenure, which when combined with the information contained in the 1840 tithe map, allows us to join the dots and with varying degrees of confidence place individual farmers at specific farms in 1808.

One such is Benjamin Pavyer, who was undoubtedly the tenant of Church Farm and James Hawley, who was at the house now known as The Cottage, but others like Anthony Rowland, whose almost 800 acres encompassed broad swathes of land, are much harder to connect with any specific farmstead. Indeed, as we will see, it seems he was not necessarily even permanently resident in the parish, though interestingly the indenture makes mention of a house with a “pleasure garden” in his tenure. This raises the intriguing possibility he was renting the manor house, or perhaps Glebe House on the High Street, with its impressive walled garden.

Frustratingly, for a farmer with such extensive lands, Anthony Rowland left a rather sparse body of evidence as to his comings, goings and doings. Presuming it to be the same person, a will for an Anthony Rowland proved in 1813 describes him as a victualler and coal dealer resident in Bradwell village, with a burial record dated 1812 backing up the place of residence and additionally putting his age at 39. A Grant of annuity by the Pelican Life Insurance Company dated 1812 (with release of annuity, 1815, 1812-1815) held by Buckinghamshire Archives (D-U/1/27) provides some further evidence that all these records relate to the same person, as the document refers to land at Great Linford, and a messuage or farmhouse formerly in the occupation of Anthony Rowland, but now in the occupation of a Luke Alibone. This sounds very much like a transaction carried out after Anthony’s death, which would fit the timeframe of the other documents. Here however the trail goes rather cold.

The Bacchus brothers, William and Richard are a better prospect for study. Cross referencing the field names in the 1808 indenture with the 1840 tithe map allows us to locate the Bacchus brothers with some confidence to Lodge Farm. However, from 1822, Richard Bacchus served as landlord of The Nags Head until his death in 1832, followed by his widow Sarah until 1865.

George Lines was born circa 1773, and though a place of birth has not yet been identified, he did leave a small paper trail of his time at Great Linford, the earliest of which is an 1803 letting agreement with Henry Uthwatt of Great Linford Manor (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/3/27) for a house and land formerly in the occupation of a man named only as Pinkard, but perhaps related to the Thomas Pinkard previously mentioned in connection to the mortgage of 1757. The grant of annuity issued by the Pelican Life Insurance Company makes further reference to George, the acreage being an exact match to the figure provided in the 1808 indenture. George clearly had ambitions, as a mortgage document by Uthwatt to Nelson, King and Hearn for £3,000 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/30) entered into 1820-1825 reveals that George had subsequently acquired several more tenures, all including farmhouses and lands, by which we can presume he may have been subletting.

In addition to his original holdings, George held 128 acres formally in the occupation of William and Richard Bacchus, plus the 199 acres formally held by John Rawlins. Sadly for George, his burgeoning empire was not to be, as he passed away in 1823 at the age of 50, having been predeceased by his wife Martha Lines, nee Shaw, a few years previously. The couple had at least eight children, baptism records at Great Linford having been located for all but one.

The Wards, Sarah and her son Philip Hoddle Ward esquire, represent one of the most intriguing names on the 1808 indenture, Philip having been one of the principal signatories; not surprising as he owned the manor of Tickford Abbey at Newport Pagnell. He had also been appointed sheriff of Buckingham in 1805. We can place the Wards in the parish from a variety of records, but most notably from a run of bad luck that afflicted two generations of the family in the 1770s.

The Northampton Mercury of April 8th, 1771, contains an appeal from John Ward, likely Philip’s father, for information (with a reward offered) concerning the theft of a Bright-Bay Mare from his grounds. This contains an interesting description of the horse, including the quirky identifying detail that it had, “a little knob on the side of her belly, done by a cow when young.”

A few years later it was the turn of Philip’s grandfather, also called Philip, to appeal for help, this time in regard to the theft of two calves. The Northampton Mercury of November 1st, 1773, includes the detail that the crime was perpetrated from a field named Great March, which also appears on the 1840 tithe map for the village, one of a trio of fields owned by the Reverend Richard Courtley and located adjacent to land destined to become the canal wharf. A Reverend Courtley is captured on the 1841 census residing in the parish of St Paul Covent Garden in London, so it appears he had invested in 46 acres of pasture in Great Linford. Philip Ward the elder passed away in 1784. He is described as a dairyman in the parish burial record, so we have evidence for a succession of Wards farming at Great Linford.

Philip Hoddle Ward and his mother are referenced again in the mortgage of 1820-1825, with the same parcel of land in their tenure, but it is what happens to Philip in later years that sets the story apart from others, as he was viciously murdered in Paris in 1844, having fled there after a financial scandal. For the story of the Ward family, click here.

The grant of annuity of 1812-1815 provide s several other names, with a piece of land measuring 77 acres, one rood and 18 perches in the occupation of Abraham Barrett called Great Marsh (north of the canal) and 82 acres, two roods and 35 perches called Little Marsh, in the occupation of a person named only as Brooks. Further research is required on these tenants if we are to pinpoint the land they worked, but it is frustrating that in this period, identifying information is extremely thin on the ground.

Newspaper advertisements for the sale or letting of farms can be equally obtuse, such as the one to be found in the Northampton Mercury of Saturday October 22nd, 1814. The owner is named as Henry Andrewes Uthwatt (of the manor house), but neither farm nor occupier is named. The only identifying information to be gleaned from the advertisement regarding its location is that the land was bisected by the canal, so a possible candidate is Windmill Hill Farm, though this is far from certain.

As we have seen then, connecting specific persons to specific farmsteads is not always possible, and indeed prior to the mid to late 1800s, farms were sporadically if at all named; in fact, with no such thing as postal addresses as we understand them today, even legal documents such as mortgages seldom contain any information that can be used to identify the name and location of a property. It is not until the 1850s that farms become more readily identifiable by name, and indeed, the impression is gained that we have reached a period in the history of the parish when farms and farmers are becoming synonymous with each other, with farmsteads becoming established as landmarks within Great Linford.

The 1861 census for Great Linford provides a useful snapshot of agricultural life in the village, as the enumerators appear to have been under instructions to obtain quite detailed information pertaining to farms. Thus we learn that there are six farmers in the village, with land ranging in size from Richard Barratt's 81 acres to Eli Elkin’s 390 acres. Between them these six farmers employed 26 men and 10 boys, though interestingly there are 87 men in the village described as agricultural labourers.

It is also notable that we have one woman running a farm, 63-year-old widow Sophia Hutchinson, who appears to have inherited the occupation of the farm upon the death of her brother John Hawley. The location of her farm is given only as “Green”, but as we have seen previously, evidence clearly placed him at farmhouse known as The Cottage. Also recorded in the same locality are two other farms, one occupied by Eli Elkins, whom we know to have been at Grange Farm on Harper’s Lane, and another by John Clode, who is to be found on the 1840 tithe map at Great Linford House, a now long-lost farmstead on land now occupied by Church Farm Crescent.

Farmers could become relatively well-to-do and can often be seen to be significant and important figures within the community, certainly a step above the average man or woman in the street. John Clode for instance styled himself as an esquire and is described as a gentleman in his will. It is not unusual to find further evidence of their standing locally, such as the frequent appointment of farmers to the board of guardians, responsible for allocating aid to the poor, and jury duty, appointments to which it must be acknowledged, were based on income, rather than any inferred acumen.

However, despite all this, most were still tenants at the whim and mercy of the landholders and could be moved or removed, with the law firmly against the farmer. For example, under a so called “distress for rent” sale, a landlord could seek to recover overdue rent, several cases of which can be found in newspaper accounts. Richard Bacchus was one such unfortunate, with a sale under a distress for rent advertised in the Northampton Mercury of November 30th, 1816, including a rick of capital old beans, two acres of excellent turnips and several ploughs. Benjamin Pavyer found himself in similar straits in November 1829, the Northampton Mercury of the 14th reporting a variety of livestock offered for sale, but also Benjamin’s household furniture, including a four-post bed and bedsteads!

The landlords are not named in these cases, but we can presume that it would have been the Uthwatts. Happily, the Bacchuss family seem to have survived their brush with penury, as the family are heavily associated with The Nags Head public house, and a Benjamin Pavyer is known to have become the village schoolmaster, so we can presume he too got back on his feet.

There was even a farmer who rented the manor house, Edward Slade, whose wife Ann had set up a private girl's school in the house between circa 1878 and 1883. Edward was recorded on the 1881 census as a farmer of 14 acres employing one boy presumably supplementing the income the couple received from school fees.

Gentleman Farmers

Animal husbandry could also be a hobby for those with the time and income to spare, and that description seems to fit for the Reverend Sydney Herbert Williams (1844-1900) of Great Linford Rectory, who owned a herd of award-winning Jersey dairy cattle. There were several other persons in the parish who we might also describe as “gentleman farmers”, including Thomas Bolding, who styled himself an esquire, and lived for a time at Ivy House (also known as Elmhurst and Linford Lodge) from circa 1833-1841. Frederick Garratt, who was a later resident of the same house, seems to have been living off investments, but the family certainly maintained a small dairy herd.

Management of farms

The Lords of the Manor would often prefer an interlocutor to manage their relationships with tenants, and we can tentatively identify several of these men, known variously as Land Agents or Bailiffs. One such is William J Samuel, who is described on the 1891 census a Land Agent and Surveyor, living in one of the finest houses in the parish, Ivy House. He may not have been the most popular man in that parish, as one of his duties was likely to have been collecting rents. Another was George Hudson; electoral rolls for 1929 and 1930 place him and his family at Lodge Farm, but we know from census records that he was by profession a farm bailiff.

A yearly ritual was a gathering of farmers called by the Lord of the Manor to undergo a rent audit, with one such meeting convened at The Black Horse Inn, with the land agent Mr George Bennett in the chair on behalf of Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt. It seems that the farmers in attendance must have left in a good mood, having enjoyed a fine meal and receiving the news of what appears to be a 10% rebate. Things did always go so well however, as on June 28th, 1910, a rent audit held at the Anchor Hotel in Newport Pagnell was brought to an shocking end when Ellis Beckett of Wood End Farm expired abruptly in his chair.

Some archaic terminology survived well into modern times as regards the business calendar, hence we often find a farmer departing a farm at Michaelmas. Traditionally there were four “quarter days” in the year, Lady Day which falls on the 25th of March, Midsummer on June 24th, Michaelmas on September 29th and Christmas day. Though these quarter days were primarily arranged around religious festivals, they also came to be used in business. Michaelmas for instance came to signify the end of the farming cycle, and was therefore often used in farming contracts, but all the quarter days were used in a similar manner, such as to pay rent instalments.

A yearly ritual was a gathering of farmers called by the Lord of the Manor to undergo a rent audit, with one such meeting convened at The Black Horse Inn, with the land agent Mr George Bennett in the chair on behalf of Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt. It seems that the farmers in attendance must have left in a good mood, having enjoyed a fine meal and receiving the news of what appears to be a 10% rebate. Things did always go so well however, as on June 28th, 1910, a rent audit held at the Anchor Hotel in Newport Pagnell was brought to an shocking end when Ellis Beckett of Wood End Farm expired abruptly in his chair.

Some archaic terminology survived well into modern times as regards the business calendar, hence we often find a farmer departing a farm at Michaelmas. Traditionally there were four “quarter days” in the year, Lady Day which falls on the 25th of March, Midsummer on June 24th, Michaelmas on September 29th and Christmas day. Though these quarter days were primarily arranged around religious festivals, they also came to be used in business. Michaelmas for instance came to signify the end of the farming cycle, and was therefore often used in farming contracts, but all the quarter days were used in a similar manner, such as to pay rent instalments.

Income from farming

If there is one constant in life, it is that the value of land increases. Thanks to the 1086 Domesday survey we can see what the parish was worth in terms of income to the four lords who possessed land at the time, a total of £7, two shillings, divided as follows: Walter Gifford £3, The Count Robert of Mortain £2, Hugh of Bolbec, £1, and William son of Ansculf, two shillings. However, for several reasons, caution should be exercised when considering these figures. First, the surveyors were interested in what was taxable from the tenants in chief; we should not therefore assume that the total figure in Domesday represents all the income to be earned from land within the parish. Second, it is impossible to make a clear like-for-like conversion of monetary values in 1086 to those in modern times. £7, two shillings does not seem a lot in modern terms, but it is illuminating to consider that thanks to the taxes he extracted throughout the country, William the Conqueror has been described as one of the ten richest men of all time.

There are some early records that provide insights into what tenant farmers were being charged, such as a 1608 deed (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/50) between the Malyns family and an Anthony Shefford for a house, three acres of arable, plus common and pasture for two kine (an archaic word for cattle) in the ley field and one cow and ten sheep in the fields and slades of Great Linford. For this, Anthony was paying £5 per annum; the National Archives currency convertor web page equates this to approximately £670 in modern money (as calculated to 2017.) In 1647, Richard Sharpe was paying £50 for a messuage and 105 acres of arable, plus ten acres of meadow, three of pasture and extensive common rights. This equates to approximately £5,175 in modern money.

The 1649 prenuptial agreement between Sir Richard Napier and Mary Kynaston attributes a value of £500 a year for the estate, which was divided into 14 parcels. We can also gain an insight into the purchase cost of land, as Richard Napier (to the later ruination of his family) was keen to extend his holdings. Elizabeth Sainsbury observes that there is evidence for increases in land value, with average prices for an acre of land running at £2 by the late 1500s, but in 1641, Richard was paying an average of £7 an acre and £10 for meadowland and some of the arable fields. At the extreme end of the scale, the approximate 60 acres of Linford Wood cost him £12, 10 Shillings and six pence per acre.

Rent books for the estate dating to the time of Sir William Prichard, who had purchased the land from the by then bankrupt Napiers in 1678, provide further information on rental income. In the late 1680s, the estate was split between land directly managed by the Prichards, and 19 tenants, paying from six shillings to £50 a year. Elizabeth Sainsbury calculates that some 700 acres had been rented out, with an average income for the Prichards of £350, equating to around £40,000 in modern terms, though the entire estate was worth around £1000 a year by the 1690s, or around £120,000. In 1714, Thomas Shilborn and Ralph Coleman had paid £110 a year for three-year lease for 203 acres of pasture. This sounds like a sizable investment, the lease setting them back the equivalent of some £11,000 in modern terms.

The previously discussed mortgage of 1757 provides the rents paid by five famers, telling us that Philip Ward was paying the most at £1.18 per acre, whilst at the lower end of the scale, John Yeomans was paying just 68p per acre, the five farms averaging out at 85p per acre. Inflation being nothing new, we can see this represents an increase to tenants since the 1680s, who had being paying in the region of 50p an acre.

In 1886 a court case was widely reported in newspapers, as a usurper to the inheritance of the estate attempted to prove his claim. Henry Manning Uthwatt ultimately failed to wrest control from the rightful heir, William Uthwatt, but we do learn that the estate was then thought to be valued at £80,000. Definitely worth fighting over, especially as the Uthwatts owned much of the property in the village, including interests in the pubs and the wharf, the entirety worth in modern terms in the region of £6.5 million.

In 1888, the approximately 300 acres of the Green Farm (later to be renamed Grange Farm) was offered for rent by the Uthwatts for £600 per annum, which would be the rough equivalent of £50,000 today. Then in 1898, the Windmill Hill Farm was offered for sale by the Knapp family, the sales brochure telling us that the farmstead and 82 acres on offer were rented for £170 per annum. We know that Windmill Hill Farm was purchased by the Uthwatts, for £2,100, equivalent in today's money to approximately £164,000.

From the above figures, we might hazard a calculation that the Uthwatts were renting land at approximately £2 an acre, earning them in the region of £3,240 a year from their tenants, or £265,000 in modern terms. Not factoring in the relative worth of the various farmsteads in the parish, we can also estimate the total value of the land in their ownership at £41,000 or something in the region of £3.2 million.

We can find a few other subsequent references to land values in later years. Wood Farm was offered for rent for £400 in 1915, though an acrimonious dispute ensued between the sitting tenant, Robert Murray Wylie, who objected to the terms of the renewal contract, and William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt. William stuck to his guns, and promptly evicted Robert.

In 1951, the 71 acres of the Black Horse Farm, its land having been much compromised by the encroachment of the Great Linford gravel pits, was sold for £7,000, which in modern terms would be in the region of £270,000. Marsh Farm, comprising of just 25 acres of land, was bought by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation in 1973, for £40,000; the farmhouse itself was not included in the sale.

There are some early records that provide insights into what tenant farmers were being charged, such as a 1608 deed (Buckinghamshire Archives D-U/1/50) between the Malyns family and an Anthony Shefford for a house, three acres of arable, plus common and pasture for two kine (an archaic word for cattle) in the ley field and one cow and ten sheep in the fields and slades of Great Linford. For this, Anthony was paying £5 per annum; the National Archives currency convertor web page equates this to approximately £670 in modern money (as calculated to 2017.) In 1647, Richard Sharpe was paying £50 for a messuage and 105 acres of arable, plus ten acres of meadow, three of pasture and extensive common rights. This equates to approximately £5,175 in modern money.

The 1649 prenuptial agreement between Sir Richard Napier and Mary Kynaston attributes a value of £500 a year for the estate, which was divided into 14 parcels. We can also gain an insight into the purchase cost of land, as Richard Napier (to the later ruination of his family) was keen to extend his holdings. Elizabeth Sainsbury observes that there is evidence for increases in land value, with average prices for an acre of land running at £2 by the late 1500s, but in 1641, Richard was paying an average of £7 an acre and £10 for meadowland and some of the arable fields. At the extreme end of the scale, the approximate 60 acres of Linford Wood cost him £12, 10 Shillings and six pence per acre.

Rent books for the estate dating to the time of Sir William Prichard, who had purchased the land from the by then bankrupt Napiers in 1678, provide further information on rental income. In the late 1680s, the estate was split between land directly managed by the Prichards, and 19 tenants, paying from six shillings to £50 a year. Elizabeth Sainsbury calculates that some 700 acres had been rented out, with an average income for the Prichards of £350, equating to around £40,000 in modern terms, though the entire estate was worth around £1000 a year by the 1690s, or around £120,000. In 1714, Thomas Shilborn and Ralph Coleman had paid £110 a year for three-year lease for 203 acres of pasture. This sounds like a sizable investment, the lease setting them back the equivalent of some £11,000 in modern terms.

The previously discussed mortgage of 1757 provides the rents paid by five famers, telling us that Philip Ward was paying the most at £1.18 per acre, whilst at the lower end of the scale, John Yeomans was paying just 68p per acre, the five farms averaging out at 85p per acre. Inflation being nothing new, we can see this represents an increase to tenants since the 1680s, who had being paying in the region of 50p an acre.

In 1886 a court case was widely reported in newspapers, as a usurper to the inheritance of the estate attempted to prove his claim. Henry Manning Uthwatt ultimately failed to wrest control from the rightful heir, William Uthwatt, but we do learn that the estate was then thought to be valued at £80,000. Definitely worth fighting over, especially as the Uthwatts owned much of the property in the village, including interests in the pubs and the wharf, the entirety worth in modern terms in the region of £6.5 million.