Great Linford House

We can reasonably infer that Great Linford House was a rather grand residence, given that it is labelled by name quite consistently and prominently on maps issued by the Ordnance Survey over many decades. Only a few other significant buildings in the village are ever afforded such an accolade, including the Manor House and The Rectory, which speaks to the strong possibility that Great Linford House was rated amongst the finest of residences in the village. All the sadder then that it was completely erased from the landscape in the 1970s, the land now occupied by the houses and gardens of Church Farm Crescent. The approximate location of the house is indicated on the map below.

The earliest reference discovered thus far to a house of this name is carried in a number of newspapers early in 1816, though here we need to exercise some caution. The National Register (London) of January 28th, contains the following brief notice of a birth: “At Great Linford House, the Lady of Lient. Gen, Loft, of a son, her 18th child.” However, rather problematically, the Manor House has on occasion being referred to as “Great Linford House”, and muddying the waters further, we know that it had been offered for rent in September 1813. So, at exactly which house General Loft’s long-suffering wife delivered her 18th child remains in the balance. Certainly, we can presume a General would expect only the finest in living arrangements.

The earliest reference discovered thus far to a house of this name is carried in a number of newspapers early in 1816, though here we need to exercise some caution. The National Register (London) of January 28th, contains the following brief notice of a birth: “At Great Linford House, the Lady of Lient. Gen, Loft, of a son, her 18th child.” However, rather problematically, the Manor House has on occasion being referred to as “Great Linford House”, and muddying the waters further, we know that it had been offered for rent in September 1813. So, at exactly which house General Loft’s long-suffering wife delivered her 18th child remains in the balance. Certainly, we can presume a General would expect only the finest in living arrangements.

John Clode

But we can be entirely certain of our facts in 1840. A tithe map (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) produced that year shows a substantial dwelling (coloured red) set in grounds with three other fairly large outbuildings, coloured in grey. These we can take to be barns and other types of outbuildings. The map is accompanied with a ledger that tallies the acreage of the land, and apportions a taxable value to it, in this case £4, six shillings. The “house and homestead” is labelled on the map as number 80, with the leger further providing that also included were three adjacent fields to the rear. These were #76 (West Rushby Ground), #78 (Little Close) and #79 (Home Close.) In total, the land came to 17 acres, one rood and 20 perches; the latter two terms being old units of land measurement. This is obviously a rather small amount of land for a farm, but as will become clear in this history, the house has been home to several farmers in the parish, and has had a number of different uses relating to equestrian matters.

Land and property alike were owned by Henry Andrewes Uthwatt of the Manor House, but occupied by John Clode. The Clodes were a prominent family in Windsor, Berkshire, boasting amongst their ranks a Lord Mayor, and appear to have made their money in the wine trade. John was born at Windsor in 1810 to William and Elizabeth Clode and had arrived at Great Linford circa 1838.

John had married at Marlyebone in London on April 27th, 1837, the marriage entry describing him as a resident of that parish. His wife Mary Baily was from Shenley, Buckinghamshire. The marriage in London is slightly odd, as the tradition was to marry in the bride’s parish. The marriage was also by license, so a fee had been paid to avoid the posting of banns; essentially then a quickie wedding, though there is no suggestion of any scandal or impropriety.

The Clodes had a child Elizabeth Jane, born 1838 at Lathbury, and another daughter Mary Baily, born May 21st, 1839 at Great Linford. That seems solid evidence that narrows the date of their arrival in the village to 1838/39, but we can further refine this to 1838, as the electoral poll book for that year places John’s place of abode as Great Linford. The 1837 poll book placed him at Milton Keynes, though subsequently this entry was crossed out and replaced with Lathbury. The name John Clode also appears in poll book records for Aylesbury and Sherrington; the suspicion is that it is the same person, so we have a picture of someone with extensive farming interests throughout the county. That he appears in the poll books is significant, as only a handful of persons within Great Linford qualified (by reason of their income) to vote. Further evidence that John was a person of some personal wealth comes from the birth certificate of his daughter Mary, where he is described as a "gentleman", a strong indication that he was a person of independent means rather than someone with a common trade.

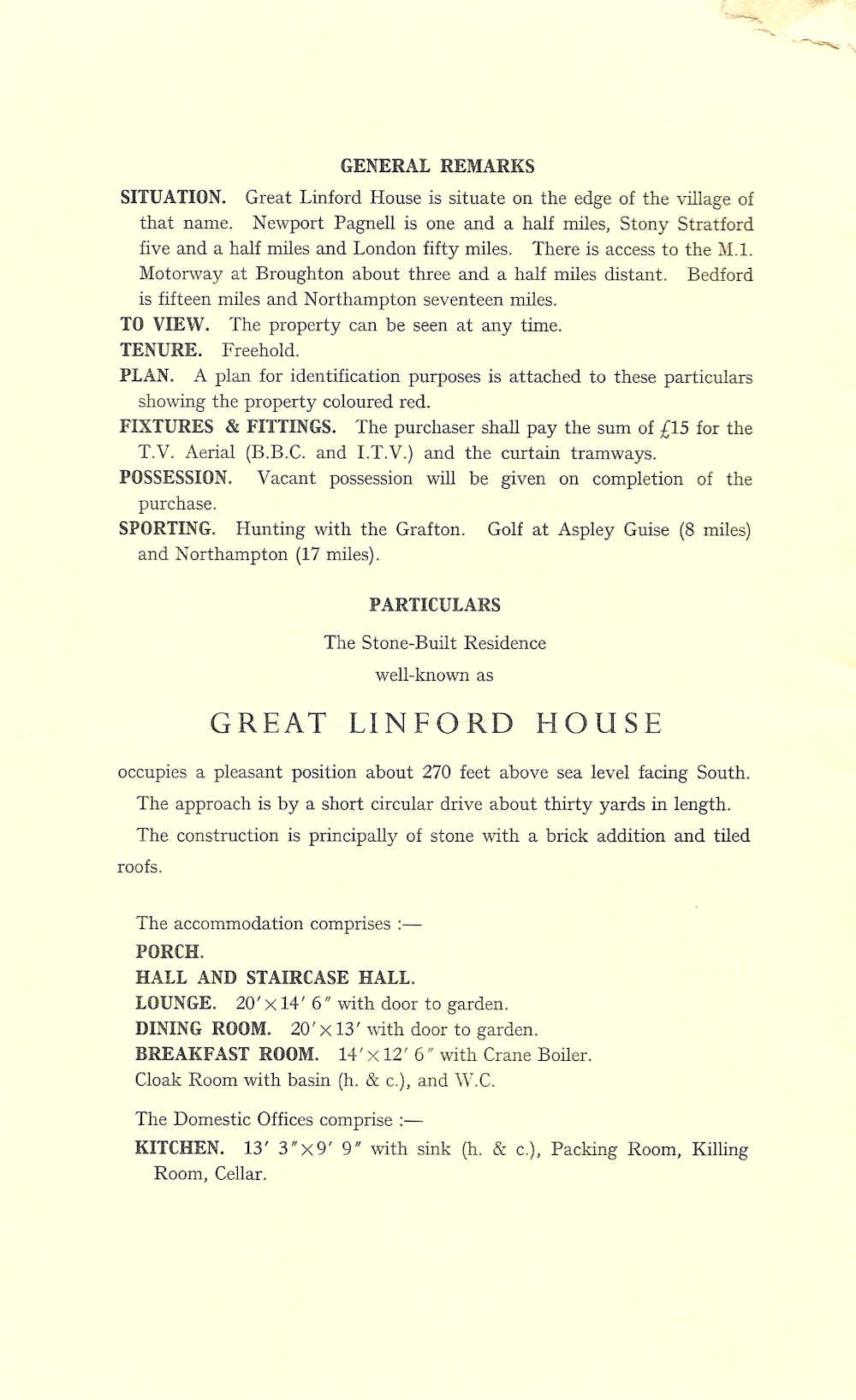

None of this information helps us ascertain the age of Great Linford House, or whom might have built it. Though we have the tenuous reference to the house in 1818, it could easily be older, and we know it was owned by the Uthwatts in 1840, so they could have built it. But can we at least tell what the house looked like? A sale notice from 1961 tells us that house was stone built, and contained a hall, three reception rooms, domestic offices, four bedrooms and a bathroom, but of course by this time it had likely gone through some degree of modification and renovation to keep it up to date; it had for instance mains electricity and water connected by 1961.

We might have an earlier description, but the provenance is by no means certain. Given that we know that the Clodes arrived in Great Linford in 1838, an examination of newspaper advertisements of houses for sale or let in the village that year throws up a description of a property that sounds grand enough to be Great Linford House, though arguing against this, no mention is made of land. The advertisement, carried in the Northampton Mercury of April 21st, reads as follows:

John had married at Marlyebone in London on April 27th, 1837, the marriage entry describing him as a resident of that parish. His wife Mary Baily was from Shenley, Buckinghamshire. The marriage in London is slightly odd, as the tradition was to marry in the bride’s parish. The marriage was also by license, so a fee had been paid to avoid the posting of banns; essentially then a quickie wedding, though there is no suggestion of any scandal or impropriety.

The Clodes had a child Elizabeth Jane, born 1838 at Lathbury, and another daughter Mary Baily, born May 21st, 1839 at Great Linford. That seems solid evidence that narrows the date of their arrival in the village to 1838/39, but we can further refine this to 1838, as the electoral poll book for that year places John’s place of abode as Great Linford. The 1837 poll book placed him at Milton Keynes, though subsequently this entry was crossed out and replaced with Lathbury. The name John Clode also appears in poll book records for Aylesbury and Sherrington; the suspicion is that it is the same person, so we have a picture of someone with extensive farming interests throughout the county. That he appears in the poll books is significant, as only a handful of persons within Great Linford qualified (by reason of their income) to vote. Further evidence that John was a person of some personal wealth comes from the birth certificate of his daughter Mary, where he is described as a "gentleman", a strong indication that he was a person of independent means rather than someone with a common trade.

None of this information helps us ascertain the age of Great Linford House, or whom might have built it. Though we have the tenuous reference to the house in 1818, it could easily be older, and we know it was owned by the Uthwatts in 1840, so they could have built it. But can we at least tell what the house looked like? A sale notice from 1961 tells us that house was stone built, and contained a hall, three reception rooms, domestic offices, four bedrooms and a bathroom, but of course by this time it had likely gone through some degree of modification and renovation to keep it up to date; it had for instance mains electricity and water connected by 1961.

We might have an earlier description, but the provenance is by no means certain. Given that we know that the Clodes arrived in Great Linford in 1838, an examination of newspaper advertisements of houses for sale or let in the village that year throws up a description of a property that sounds grand enough to be Great Linford House, though arguing against this, no mention is made of land. The advertisement, carried in the Northampton Mercury of April 21st, reads as follows:

To be let, and may be entered on immediately. A house and garden, situated at Great Linford, Bucks; comprising two parlours, hall, back kitchen, dairy, cellar, three good sleeping rooms and attic; also stable, wood barn, all necessary outbuildings, and pump of excellent water in back kitchen. For particulars, apply to Mr Elkins, Great Linford.

Mr Elkins would be Eli Elkins, of the Grange Farm (also known as Green Farm) and since we know he was a resident elsewhere in the village, it seems reasonable to presume the advert refers to another property in the village. The description does also make it sound quite substantial, especially as regards the outbuildings, so perhaps this is Great Linford House, and the advert caught the eye of the Clodes? It should be noted however that Eli was then in the "occupation" of three farmsteads in the village, Grange Farm, The Mead and Wood End Farm, so we must exercise a great deal of caution in attributing the above description to Great Linford House.

The 1841 census has no information that identifies the house by name or location within the village, but it does tell us that John Clode and his wife were present on the day of the census, along with their young daughters, Elizabeth (aged three) Mary (aged two) and an unnamed two-month-old child. Also in the household we find no less than four female servants. The 1851 census provides a description of the servants' duties, naming a governess, a nursemaid (there is then a new two-month-old child to look after) and a cook. Under the heading of profession for John, we find the abbreviated term "Ind", short for independent means. This means that in essence he did not have to work for a living but was likely deriving an income from investments or land.

Trade directories provide a useful insight into the status of the Clodes in the village, as the persons these publications list in each locality are generally subdivided between gentry and traders. The 1847 Post Office directory categorises John as a member of the gentry, thereby placing him just below the nobility within the social pecking order. Altogether, the evidence paints a picture of a high-status house and well-to-do residents who could afford to employ a large staff.

It is however notable that John Clode is described as a farmer on the 1851 and 1861 census records, the latter adding the detail that he was employing two men and his farmland was 420 acres in extent, far more than the paltry 17 acres that came with Great Linford House. However, exactly where this additional land was, and under what circumstances john came to farm it, is somewhat uncertain. It is clear that in later years the Clodes had a connection to the adjacent farmhouse now known as The Cottage, and also that a pattern developed of farmers moving back and forth between Lodge Farm and Great Linford House, but this cannot in itself account for the location of the additional land without further evidence.

The 1861 census captured a very busy household, headed by John, with his wife Mary, nine children ranging in age from three to 23, a new governess, four servants, plus one visitor. Perhaps maintaining such a large household had put a strain on the family finances, necessitating the need for John to supplement his income, but equally he may have been farming as a hobby, as a so-called gentleman farmer.

By time of the 1871 census, his 420 acres was providing employment for three labourers and five boys, though by 1881 the farmland accredited to him had shrunk markedly to 195 acres; though still sufficient to employ six men and two boys. Also in 1881, the first 25 inch to mile map of the parish was issued by the Ordnance Survey, showing Great Linford House. Click here to view the 1881 O.S. map.

The 1891 census records John and his wife, along with children and grandchildren living on the “High Street”, though in all likelihood they were still at Great Linford House, given that technically speaking, it was located on the Green end of the High Street. John is now described as a retired gentleman. He died on December 22nd, 1894, and was buried on Boxing Day at Great Linford. The Buckingham Express of January 5th, 1895, carried the following obituary.

The 1841 census has no information that identifies the house by name or location within the village, but it does tell us that John Clode and his wife were present on the day of the census, along with their young daughters, Elizabeth (aged three) Mary (aged two) and an unnamed two-month-old child. Also in the household we find no less than four female servants. The 1851 census provides a description of the servants' duties, naming a governess, a nursemaid (there is then a new two-month-old child to look after) and a cook. Under the heading of profession for John, we find the abbreviated term "Ind", short for independent means. This means that in essence he did not have to work for a living but was likely deriving an income from investments or land.

Trade directories provide a useful insight into the status of the Clodes in the village, as the persons these publications list in each locality are generally subdivided between gentry and traders. The 1847 Post Office directory categorises John as a member of the gentry, thereby placing him just below the nobility within the social pecking order. Altogether, the evidence paints a picture of a high-status house and well-to-do residents who could afford to employ a large staff.

It is however notable that John Clode is described as a farmer on the 1851 and 1861 census records, the latter adding the detail that he was employing two men and his farmland was 420 acres in extent, far more than the paltry 17 acres that came with Great Linford House. However, exactly where this additional land was, and under what circumstances john came to farm it, is somewhat uncertain. It is clear that in later years the Clodes had a connection to the adjacent farmhouse now known as The Cottage, and also that a pattern developed of farmers moving back and forth between Lodge Farm and Great Linford House, but this cannot in itself account for the location of the additional land without further evidence.

The 1861 census captured a very busy household, headed by John, with his wife Mary, nine children ranging in age from three to 23, a new governess, four servants, plus one visitor. Perhaps maintaining such a large household had put a strain on the family finances, necessitating the need for John to supplement his income, but equally he may have been farming as a hobby, as a so-called gentleman farmer.

By time of the 1871 census, his 420 acres was providing employment for three labourers and five boys, though by 1881 the farmland accredited to him had shrunk markedly to 195 acres; though still sufficient to employ six men and two boys. Also in 1881, the first 25 inch to mile map of the parish was issued by the Ordnance Survey, showing Great Linford House. Click here to view the 1881 O.S. map.

The 1891 census records John and his wife, along with children and grandchildren living on the “High Street”, though in all likelihood they were still at Great Linford House, given that technically speaking, it was located on the Green end of the High Street. John is now described as a retired gentleman. He died on December 22nd, 1894, and was buried on Boxing Day at Great Linford. The Buckingham Express of January 5th, 1895, carried the following obituary.

GREAT LINFORD. FUNERAL OF MR. JOHN CLODE.- On Wednesday, December 26th, the remains of Mr. John Clode, of Great Linford, who died at the advanced age of 84, were interred here. In the year 1838 Mr. Clode joined the Royal Bucks Yeomanry, and during his connection he made many friends, two of his chief personal friends being the late Major Levi and Major Lucas, the latter predeceasing him many years, and the former but a few years. In 1864 he resigned as captain. For upwards of 55 years Mr. Clode resided in the perish of Great Linford, and for half-a-century performed the office of Rector's Warden under several rectors. At one time he was an ardent supporter of outdoor exercises, and figured both in the hunting and cricket field. His death, though occurring at an advanced age, has come as a severe blow upon the members of his family, for he was a loving and tender parent.

It seems notable that no mention is made of John's activities as a farmer, but his finances appear to have been in a robust state, as he left an estate of just under £6000 (in the region of £500,000 in modern term.) He is buried alongside many other members of the family in St. Andrew’s churchyard. Further testifying to the standing of the family, a brass plaque commemorating his passing is affixed to a wall within the church. However, the family must have surrendered the occupancy of Great Linford House shortly after John’s death, as at the time of the 1901 census there are no Clodes left in the village, the 11 children having either died or had become scattered around the country. John’s wife had also left for Bedford, though she was subsequently interred alongside her husband at Great Linford upon her death in 1899.

William and Percy Hedges

The 1901 census gives us a new resident at Great Linford House, 45-year-old William Hedges, his wife Martha and three young children. William had been born in Stewkley in Buckinghamshire in 1855 and married Martha Dickins at Oxhey in Hertforshire in 1887. The Kelly’s trade directory of 1887 places them in the village at an unnamed farm, with the 1891 census locating them at Lodge Farm. We can surmise that he was subletting from John Clode, and that upon John's passing, the Hedges seized the opportunity to move into one of the best houses in the village.

It does seem that occupying Great Linford House was a sure sign of success. As previously observed, John Clode had farming interests elsewhere in the parish, and a valuation office survey map produced for the parish in 1910 (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5) confirms that William Hedges's farming interests were extensive. Not only is there the 20 acres ascribed to Great Linford House, but William is also occupying the 214 acres of the Black Horse Farm and the 313 acres of Lodge Farm, a grand total of 550 acres, making him by far the largest farmer by acreage in the parish. He was however still only a tenant, the tax map confirming that all these properties and their land remained firmly in the ownership of William Uthwatt.

It does seem that occupying Great Linford House was a sure sign of success. As previously observed, John Clode had farming interests elsewhere in the parish, and a valuation office survey map produced for the parish in 1910 (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5) confirms that William Hedges's farming interests were extensive. Not only is there the 20 acres ascribed to Great Linford House, but William is also occupying the 214 acres of the Black Horse Farm and the 313 acres of Lodge Farm, a grand total of 550 acres, making him by far the largest farmer by acreage in the parish. He was however still only a tenant, the tax map confirming that all these properties and their land remained firmly in the ownership of William Uthwatt.

Newspaper accounts, such as a notice of the birth of a daughter Dorothy in 1900 and the wedding of another Daughter, Winifred in August of 1918, continue to place the family at Great Linford House. At least two sons served in World War I; Stanley was a dispatch rider in Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) and Percy was reported wounded in 1915. In common with other gentleman farmers of the village, William took up public office. For instance, we find him nominated alongside William Uthwatt as an overseer of the parish in 1894.

William Hedges died on July 7th, 1921 of pneumonia and pleurisy. His passing was reported upon in several newspapers, including the Northampton Chronicle and Echo of July 11th, which described him as a, “well-known North Bucks farmer who had lived in the village 35 years.” The obituary also went on to state that he had been one of the largest agriculturists in the northern part of Bucks, and that up to a short time ago had farmed 1,000 acres of land; notably double what was reported in 1910, and since if seems unlikely he had further extended his holdings in Great Linford, we might speculate that had he land tenancies in other parishes. Additionally, we learn that his dairy herd of between 80 and 100 cows had won many prizes and he had also been successful in the breeding of shire horses.

The Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of July 23rd, carried an obituary focusing on his farming achievements, including that he regularly sold stock of all sorts at livestock sales at Fenny Stratford and Bletchley. He was also a member of the Cattle Shows and Market committee, and hardly ever missed a meeting, bringing the same energy to his membership of the Bletchley and district branch of the National Farmers’ Union.

William’s son Percy took over the running of the farm, but within a few years, his father’s carefully built business legacy was in disarray and Percy was facing disaster. The Bucks Herald of October 25th, 1924, carries a bankruptcy notice stating that “a meeting of creditors of Percy Robert Hedges, farmer, Linford House, was held on Friday week.” The notice casts some veiled aspersions against Percy, offering the opinion that he had, “started with ample capital, and the particulars of where the money had gone would have to be supplied.” The Northampton Mercury of November 7th offers a more substantive account of the circumstances, with the cause of failure given as “want of capital and loss on farming.” In his defense, farming in general had gone into decline in the years after his father’s death, and Percy had sought loans from money lenders at exorbitant rates of interest. It also confirms that the family were living still at Linford House, but farming at Lodge Farm.

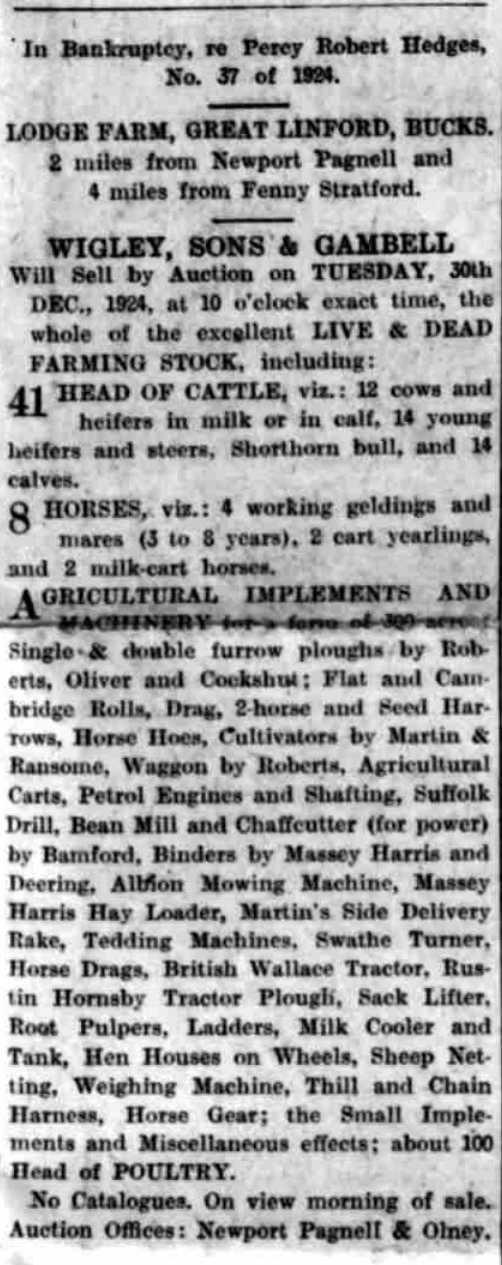

By December of 1924, the Wolverton Express of the 26th was carrying an advertisement for the sale of the live and dead farming stock at Lodge Farm, along with an extensive list of farm machinery and implements.

William Hedges died on July 7th, 1921 of pneumonia and pleurisy. His passing was reported upon in several newspapers, including the Northampton Chronicle and Echo of July 11th, which described him as a, “well-known North Bucks farmer who had lived in the village 35 years.” The obituary also went on to state that he had been one of the largest agriculturists in the northern part of Bucks, and that up to a short time ago had farmed 1,000 acres of land; notably double what was reported in 1910, and since if seems unlikely he had further extended his holdings in Great Linford, we might speculate that had he land tenancies in other parishes. Additionally, we learn that his dairy herd of between 80 and 100 cows had won many prizes and he had also been successful in the breeding of shire horses.

The Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of July 23rd, carried an obituary focusing on his farming achievements, including that he regularly sold stock of all sorts at livestock sales at Fenny Stratford and Bletchley. He was also a member of the Cattle Shows and Market committee, and hardly ever missed a meeting, bringing the same energy to his membership of the Bletchley and district branch of the National Farmers’ Union.

William’s son Percy took over the running of the farm, but within a few years, his father’s carefully built business legacy was in disarray and Percy was facing disaster. The Bucks Herald of October 25th, 1924, carries a bankruptcy notice stating that “a meeting of creditors of Percy Robert Hedges, farmer, Linford House, was held on Friday week.” The notice casts some veiled aspersions against Percy, offering the opinion that he had, “started with ample capital, and the particulars of where the money had gone would have to be supplied.” The Northampton Mercury of November 7th offers a more substantive account of the circumstances, with the cause of failure given as “want of capital and loss on farming.” In his defense, farming in general had gone into decline in the years after his father’s death, and Percy had sought loans from money lenders at exorbitant rates of interest. It also confirms that the family were living still at Linford House, but farming at Lodge Farm.

By December of 1924, the Wolverton Express of the 26th was carrying an advertisement for the sale of the live and dead farming stock at Lodge Farm, along with an extensive list of farm machinery and implements.

This sale seems to signal the end of the Hedges family's connection to Great Linford. In November of 1925, Percy is reported to have had a run-in with the law for having failed to display a road fund license on a motor vehicle in Northamptonshire. The account of this infraction is carried in the Northampton Mercury of the 6th and fixes Percy’s abode at Kelmarsh in Northamptonshire, as well as providing the detail that he was then employed as a farm bailiff. Percy did eventually have his bankruptcy discharged in 1931, but by then was living in Bushey. Herts and working for his brother.

The Sharpes

The electoral roll records for the parish can shed light on the next occupiers of Great Linford House, though it raises the possibility that the property had lain unoccupied for several years, as there is a gap between Percy’s departure in 1924 and the appearance of a new family at the property in 1927. Equally of course, it could be that Frederick William Sharpe and Matilda Sharpe (nee Shawley) had neglected to register as voters at Great Linford House until then. Whatever the case, by 1928 they had been joined by their son Robert Oscar and his wife Mary, though the following year the only persons registered to vote at the address are Robert and Mary. An article concerning Robert’s appointment as chair of the Newport Pagnell branch of the National Farmers Union published in the Wolverton Express of December 19th, 1952 tells us that father and son had once been in partnership, but that this has been dissolved. We can presume this has happened circa 1929; Frederick and Matilda then moving to Ampthill, Bedfordshire.

The Sharpes were not resident at Great Linford for long and make little in the way of a splash in the newspapers, but from what we can find, they do seem to have slipped comfortably into the rhythm of local life. Robert for instance is seen rubbing shoulders with Major Charles Walter Mead of the Manor House on the occasion of a bazaar held at Bradwell’s Primitive Methodist Church. It was opened by Major Mead, but “presided over” by Robert. In fact, the Sharpes were committed Methodists, with several generations taking on the role of preacher, including Robert. Robert was also a cricketer and can be found on a village team that played Shenley in July of 1932. We then find he and Major Mead together again, this time at a flower show held in Great Linford’s memorial hall in August of 1932. Additionally, the 1929 electoral roll confirms that Robert was a jurist, a firm indication of his standing in the community.

Robert’s wife was equally active locally. In August 1930, she is credited as an “elocutionist” at the aforementioned Bradwell church. This is defined as a public speaker trained in voice production and gesture and delivery. Similarly she provided “recitations” at a Women’s Institute event in October the same year. She was also reported to have been the chair at a Congregationalists meeting at Whaddon in January 1933.

Clearly the Sharpes were keeping busy, but next to nothing can be found regarding their business interests whilst living in the parish. Not until Frederick’s death do we gain an understanding of his farming career, but though his obituary carried in The Bedfordshire Times and Independent of November 9th, 1934 is an extensive one, it completely omits any mention of his admittedly brief tenure at Great Linford.

We do have one rather unfortunate reference to the Sharpes in the village, from a court case reported in the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of March 3rd, 1934. The case was one of alleged cruelty to horses, the defendants being Robert Oscar Sharp (spelt without the customary e) and his son Robert Samuel Sharp. The location of the offence is given as Lodge Farm, at which place Robert Jnr was allegedly witnessed striking a horse 20 times with an ash stick while ploughing. However, lacking any physical evidence of injury to the horse, the case was dismissed.

The last reference to the Sharpes in the parish comes from a brief account in the Northampton Chronicle and Echo of October 1st, 1931. The newspaper reports that an “Oscar Sharpe, farm worker, of Linford House”, was summoned for having ridden his bike without a rear red light, receiving a five shilling fine for his troubles. Not long after this the family moved to Wood Farm at Moulsoe.

The Sharpes were not resident at Great Linford for long and make little in the way of a splash in the newspapers, but from what we can find, they do seem to have slipped comfortably into the rhythm of local life. Robert for instance is seen rubbing shoulders with Major Charles Walter Mead of the Manor House on the occasion of a bazaar held at Bradwell’s Primitive Methodist Church. It was opened by Major Mead, but “presided over” by Robert. In fact, the Sharpes were committed Methodists, with several generations taking on the role of preacher, including Robert. Robert was also a cricketer and can be found on a village team that played Shenley in July of 1932. We then find he and Major Mead together again, this time at a flower show held in Great Linford’s memorial hall in August of 1932. Additionally, the 1929 electoral roll confirms that Robert was a jurist, a firm indication of his standing in the community.

Robert’s wife was equally active locally. In August 1930, she is credited as an “elocutionist” at the aforementioned Bradwell church. This is defined as a public speaker trained in voice production and gesture and delivery. Similarly she provided “recitations” at a Women’s Institute event in October the same year. She was also reported to have been the chair at a Congregationalists meeting at Whaddon in January 1933.

Clearly the Sharpes were keeping busy, but next to nothing can be found regarding their business interests whilst living in the parish. Not until Frederick’s death do we gain an understanding of his farming career, but though his obituary carried in The Bedfordshire Times and Independent of November 9th, 1934 is an extensive one, it completely omits any mention of his admittedly brief tenure at Great Linford.

We do have one rather unfortunate reference to the Sharpes in the village, from a court case reported in the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of March 3rd, 1934. The case was one of alleged cruelty to horses, the defendants being Robert Oscar Sharp (spelt without the customary e) and his son Robert Samuel Sharp. The location of the offence is given as Lodge Farm, at which place Robert Jnr was allegedly witnessed striking a horse 20 times with an ash stick while ploughing. However, lacking any physical evidence of injury to the horse, the case was dismissed.

The last reference to the Sharpes in the parish comes from a brief account in the Northampton Chronicle and Echo of October 1st, 1931. The newspaper reports that an “Oscar Sharpe, farm worker, of Linford House”, was summoned for having ridden his bike without a rear red light, receiving a five shilling fine for his troubles. Not long after this the family moved to Wood Farm at Moulsoe.

The Dickins

Sometime in the early 1930s the Sharpes vacated Great Linford House for Lodge Farm, and we then begin to find references to the name Dickins, generally in the person of a Mrs K Dickins, who was by all accounts an accomplished horse rider. However, the earliest reference to the family residing in the village actually concerns a dog show at Tring, where a Mrs Dickins of Great Linford House won a prize, as reported in the Bucks Herald of August 12th, 1932.

Jessie Flint had been born in Southorpe in Northamptonshire circa 1886, and in 1907 had married William Everard Dickins in Lincolnshire, the couple settling in the village of Billingborough. Sadly, William passed away in 1921 aged 38 years, and it was to Great Linford that the widowed Jessie relocated in the early 1930s. The couple appear to have had one daughter, though there is some confusion as to her name, as some accounts name her Phyliss (she was baptised as such), and others as the aforementioned K. Dickins. Either way, newspaper accounts are unanimous that William and Jessie had only one child.

While Jessie was still living in Lincolnshire, the Grantham Journal of May 17th, 1930, reported on the equestrian achievements of her only daughter “K. Dickins”, who had passed her examination in equitation, horse training and stable management held at the Duke of York’s Riding School in London, where she had been awarded a first class certificate. The article also offers that had been “distinctly successful in the showring, having won numerous prizes.”

Reflecting the confusion over names, a report in the Louth Standard dated August 21st, 1931, lists an impressive tally of equestrian wins for a Phyliss Dickins, who is clearly identified in the article as the only daughter of William and Jessie Dickins. It also states that Phyliss had a riding school in Kent. It does seem though that she subsequently relocated along with her mother to Great Linford, as under the name K Dickins, she is reported to have been a resident in the village in 1933, the Sevenoaks Chronicle and Kentish Advertiser of August 18th, observing that she had, “won outright the 50-guinea silver cup” at the 37th annual horse show at the East-Sussex village of Cross-in-Hand. She was riding a horse named Fizzer. Other prize winning horses named in this period are Gamecock and Adjutant.

We might reasonably presume that Jessie and her daughter were running some kind of equestrian enterprise from Great Linford House, and it is certainly the case that they employed a groom. His name was Reginald Stanley Vanstone, and in June of 1934 he was hauled before the Newport Pagnell Petty Sessions to answer a charge of having run up “affiliation arrears.” This meant he was supporting a child born out of wedlock, and it was the mother, Margaret Marjorie Raymond, of Grange Cottage who had summoned him to appear. Reginald did not take to this kindly, and after telling the chairman of the bench, “you don’t reckon to pay for something you haven’t had”, was sent down for one month’s imprisonment.

Troubles with staff aside, we can be sure the Dickins were engaged in more general types of farming. The Kelly’s trade directory of 1935 describes Jessie Dickins of Great Linford House as a farmer, and when in October of 1937 she announced her intention to leave the village, an advertisement carried in the Bedfordshire Times and Independent of October 15th listed for sale 28 head of Shorthorn cattle, 121 sheep and two horses. Exactly where this not insubstantial collection of livestock was being grazed is not certain.

Jessie Flint had been born in Southorpe in Northamptonshire circa 1886, and in 1907 had married William Everard Dickins in Lincolnshire, the couple settling in the village of Billingborough. Sadly, William passed away in 1921 aged 38 years, and it was to Great Linford that the widowed Jessie relocated in the early 1930s. The couple appear to have had one daughter, though there is some confusion as to her name, as some accounts name her Phyliss (she was baptised as such), and others as the aforementioned K. Dickins. Either way, newspaper accounts are unanimous that William and Jessie had only one child.

While Jessie was still living in Lincolnshire, the Grantham Journal of May 17th, 1930, reported on the equestrian achievements of her only daughter “K. Dickins”, who had passed her examination in equitation, horse training and stable management held at the Duke of York’s Riding School in London, where she had been awarded a first class certificate. The article also offers that had been “distinctly successful in the showring, having won numerous prizes.”

Reflecting the confusion over names, a report in the Louth Standard dated August 21st, 1931, lists an impressive tally of equestrian wins for a Phyliss Dickins, who is clearly identified in the article as the only daughter of William and Jessie Dickins. It also states that Phyliss had a riding school in Kent. It does seem though that she subsequently relocated along with her mother to Great Linford, as under the name K Dickins, she is reported to have been a resident in the village in 1933, the Sevenoaks Chronicle and Kentish Advertiser of August 18th, observing that she had, “won outright the 50-guinea silver cup” at the 37th annual horse show at the East-Sussex village of Cross-in-Hand. She was riding a horse named Fizzer. Other prize winning horses named in this period are Gamecock and Adjutant.

We might reasonably presume that Jessie and her daughter were running some kind of equestrian enterprise from Great Linford House, and it is certainly the case that they employed a groom. His name was Reginald Stanley Vanstone, and in June of 1934 he was hauled before the Newport Pagnell Petty Sessions to answer a charge of having run up “affiliation arrears.” This meant he was supporting a child born out of wedlock, and it was the mother, Margaret Marjorie Raymond, of Grange Cottage who had summoned him to appear. Reginald did not take to this kindly, and after telling the chairman of the bench, “you don’t reckon to pay for something you haven’t had”, was sent down for one month’s imprisonment.

Troubles with staff aside, we can be sure the Dickins were engaged in more general types of farming. The Kelly’s trade directory of 1935 describes Jessie Dickins of Great Linford House as a farmer, and when in October of 1937 she announced her intention to leave the village, an advertisement carried in the Bedfordshire Times and Independent of October 15th listed for sale 28 head of Shorthorn cattle, 121 sheep and two horses. Exactly where this not insubstantial collection of livestock was being grazed is not certain.

James Barry Gloster

It does seem that the arrival of Jessie Dickins and her daughter marked the beginning of a period in the history of the house when it became closely connected to people of an equestrian inclination. The next name we can associate with the house is James Barry Gloster, who marketed himself as an inventor and horse trainer extraordinaire, able to placate the most unruly of nags. He had a horse called Mavourneen, that he exhibited widely as an “ex-maneating mare”, and which he had taught to dance to gramophone music. The Kelly’s trade directory published in 1939, lists James Gloster as the owner of a riding school. It is noteworthy that between one of the outbuildings was expanded in size whilst James was resident at the house, perhaps indicating that he was increasing his capacity to house recalcitrant horses. The change can be seen by comparing the 1948 Ordnance Survey map with the 1955 Ordnance Survey map. For more on the story of James Gloster and Mavourneen, click here.

The Nagingtons

|

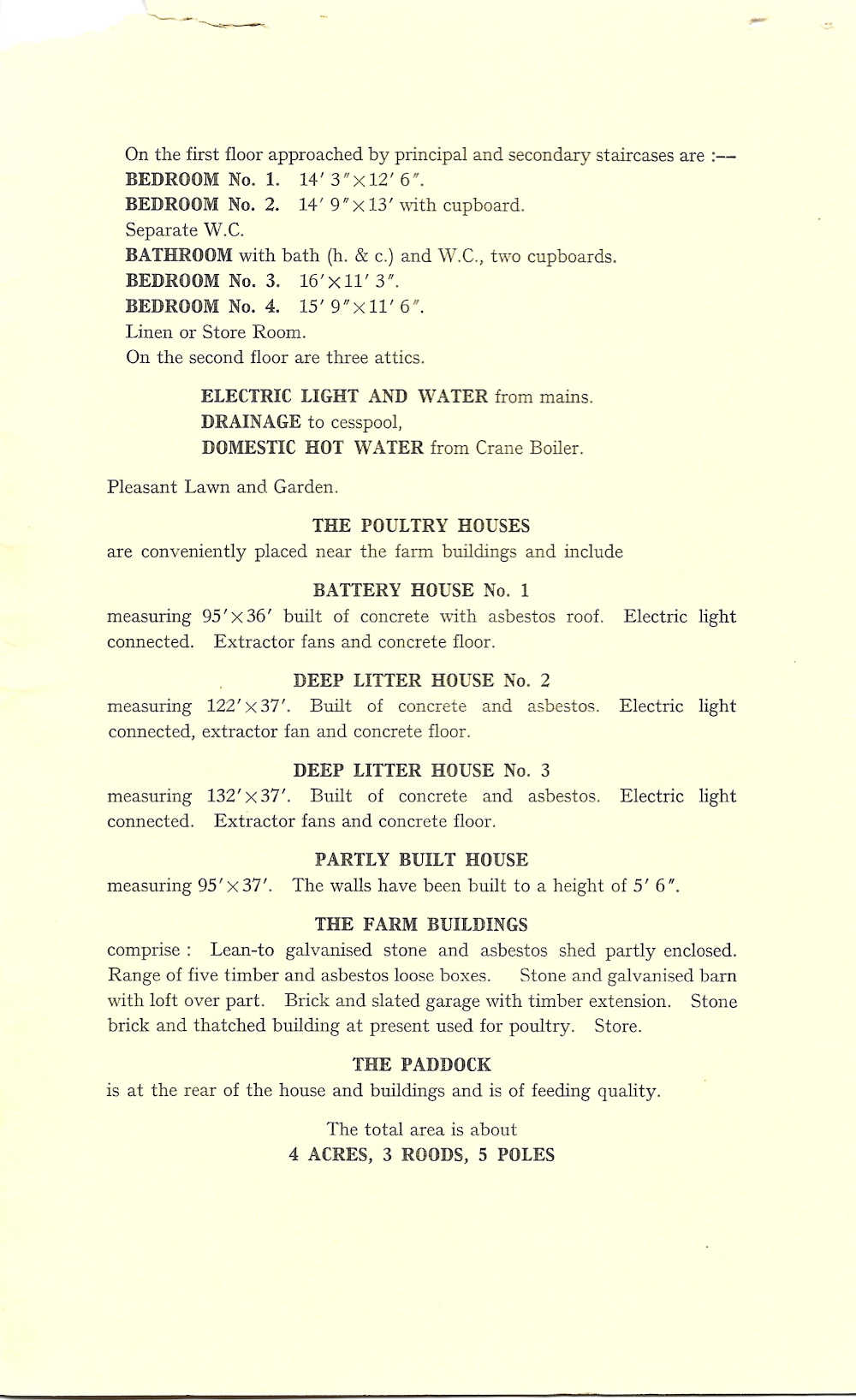

James Gloster left Great Linford circa 1956 to live in West Sussex, and a Frank Nagington then purchased the house, with a very different idea of what to use the property for. The Bucks Standard of June 28th, 1958, carries an extensive article about their "broiler business", a pioneering enterprise at the time for the intensive rearing of chickens. The Nagingtons had actually been living in the village already for several years at the Old Rectory, then known as Grey Gables. The article states that the Nagingtons were rearing in the region of 20,000 chickens at Great Linford House and 8000 at Grey Gables, so it was clearly an extensive operation, trading under the name Great Linford Enterprises and including two shops, one in Newport Pagnell and the other at Bletchley.

|

Such was the interest in the Nagington’s farm that the BBC dispatched a “Commander Villiers” to record an episode of the radio show “Town and Country”, which was broadcast on the evening of June 24th, 1958. Commander Villiers appears have been Alan Villiers, described on his Wikipedia entry as a writer, adventurer, photographer and mariner. The walk and talk described as having taken place around Frank’s farm seems rather tame for a man of Commander Villiers’ impressive CV, but sadly no recording of the programme has yet come to light.

The earlier life story of the Nagingtons is rather hazy at present. An extensive article on their business at Great Linford (Bucks Standard, June 28th, 1958) alludes to a severe accident at Frank’s prior farm near Oxford, which forced him to seek lighter work. However no other evidence can be found for this farm; we know only that he had married an Agnes Maud Moore at Birmingham in 1943. Sadly, the Nagingtons had a terrible run of luck at Great Linford, beginning on November 3rd, 1959, when a fire ripped through a single-story timber poultry house, killing almost 2000 five month old chickens.

This calamity occurred in the grounds of Grey Gables, as did a second fire toward the end of May 1960. The grim toll was again another 2000 chickens. The story carried in the Bucks Standard of June 1st, indicates that the house was adjacent to the Nags Head pub, and indeed the evidence of both an advert in the Times newspaper of June 16th, and a the sales brochure produced by the auctioneer, Jackson-Stops & Staff, proves categorically that Grey Gables was the name that the Old Rectory was then known by. The landlord and landlady of the Nags Head were first hand witnesses to both fires, and in the case of the former, it was touch and go if the inferno would spread to the thatch of the pub.

The Times newspaper of June 16th, 1960, carried an advert for the sale of Grey Gables (undoubtedly the rectory as the advert and sales brochure carried a picture) with the ominous note that the sale was being conducted under the auspices of the "court of protection", meaning that there was some question over the competency of Frank to administer his affairs.

The aforementioned article in the Bucks Standard also tells us that Frank had been unwell for several months, and the business was being looked after by his wife, though things were not going well. The Wolverton Express of March 31st, 1961, reported that Agnes was being pursued for the return of two scales, having not kept up with the hire purchase payments. After it’s rather spectacular early success, the luster was clearly coming off the business, and so it can come as no surprise that the double whammy of the fires, likely coupled with Frank’s illness, signaled the death knell for the business.

The Bucks Standard of August 5th, 1961, was one of several local newspapers that carried a notification of the sale of Great Linford House, along with all the accoutrements of the broiler business and around 4½ acres of land. The adverts have the same ominous tone as was conveyed in the sale of Grey Gables, in that they were issued by an order of the court of protection. This is confirmed by the sales brochure issued by Jackson-Stops & Staff, which also states the sale was to be held under an order of the Court of Protection.

The sales brochure, reproduced below, affords us a detailed description of the house, including that it was stone built with a brick addition and tiled roofs. Giving some credence to the idea that it was a house of some significance, the description tell us that the amongst other rooms, the property boasted a hall and staircase hall, a lounge, dining room and a breakfast room. On the first floor were four bedrooms and a bathroom, and on the second floor three attics.

The earlier life story of the Nagingtons is rather hazy at present. An extensive article on their business at Great Linford (Bucks Standard, June 28th, 1958) alludes to a severe accident at Frank’s prior farm near Oxford, which forced him to seek lighter work. However no other evidence can be found for this farm; we know only that he had married an Agnes Maud Moore at Birmingham in 1943. Sadly, the Nagingtons had a terrible run of luck at Great Linford, beginning on November 3rd, 1959, when a fire ripped through a single-story timber poultry house, killing almost 2000 five month old chickens.

This calamity occurred in the grounds of Grey Gables, as did a second fire toward the end of May 1960. The grim toll was again another 2000 chickens. The story carried in the Bucks Standard of June 1st, indicates that the house was adjacent to the Nags Head pub, and indeed the evidence of both an advert in the Times newspaper of June 16th, and a the sales brochure produced by the auctioneer, Jackson-Stops & Staff, proves categorically that Grey Gables was the name that the Old Rectory was then known by. The landlord and landlady of the Nags Head were first hand witnesses to both fires, and in the case of the former, it was touch and go if the inferno would spread to the thatch of the pub.

The Times newspaper of June 16th, 1960, carried an advert for the sale of Grey Gables (undoubtedly the rectory as the advert and sales brochure carried a picture) with the ominous note that the sale was being conducted under the auspices of the "court of protection", meaning that there was some question over the competency of Frank to administer his affairs.

The aforementioned article in the Bucks Standard also tells us that Frank had been unwell for several months, and the business was being looked after by his wife, though things were not going well. The Wolverton Express of March 31st, 1961, reported that Agnes was being pursued for the return of two scales, having not kept up with the hire purchase payments. After it’s rather spectacular early success, the luster was clearly coming off the business, and so it can come as no surprise that the double whammy of the fires, likely coupled with Frank’s illness, signaled the death knell for the business.

The Bucks Standard of August 5th, 1961, was one of several local newspapers that carried a notification of the sale of Great Linford House, along with all the accoutrements of the broiler business and around 4½ acres of land. The adverts have the same ominous tone as was conveyed in the sale of Grey Gables, in that they were issued by an order of the court of protection. This is confirmed by the sales brochure issued by Jackson-Stops & Staff, which also states the sale was to be held under an order of the Court of Protection.

The sales brochure, reproduced below, affords us a detailed description of the house, including that it was stone built with a brick addition and tiled roofs. Giving some credence to the idea that it was a house of some significance, the description tell us that the amongst other rooms, the property boasted a hall and staircase hall, a lounge, dining room and a breakfast room. On the first floor were four bedrooms and a bathroom, and on the second floor three attics.

While a photograph of Great Linford House has yes to have positively identified, a possible image does exist. Between 1912-1913, photographers were dispatched to capture pictures of interesting buildings and structures in Buckinghamshire, some of which were reproduced in two volumes produced by the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments. The image reproduced below was not chosen to appear in this publication, but is held by the Buckinghamshire Archives (phx/214/a), though no label is attributed to it, only that it was a house in Great Linford. It certainly matches no surviving house in the parish, and it is a substantial structure, of stone construction (though no obvious brick addition, though this may have come later) and clearly having two floors, and with more than sufficient space to house the attics described in the sales brochure.

The Coventry Evening Telegraph of September 6th, 1962, carried a notice seeking persons to come forward who were , owned money by Frank Nagington, then living in Coventry, but hereafter we lose track of him, though in later years his wife can be found running a market stall selling eggs in the same city. As a final footnote to their story, she was prosecuted in March of 1963 for allegedly tampering with the official markings on eggs. She passed away in Coventry in 1993.

The property meanwhile had been sold in 1961 for £2,350, though the brief note carried in the Wolverton Express of September 8th, makes no mention of the buyer. The house and grounds appear on the 1968 O.S map, but the 1972 O.S map has a different story to tell. Church Farm Crescent and it’s houses has been built; the farmhouse has at least for then survived, though now renamed to Crescent Farm. Click here to view the 1972 O.S map.

One final piece of the story remains, held by the Buckinghamshire Record Office. These are copies of the conveyancing records for the purchase of the house by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation (D-MKDC/9/1/59), naming Crescent Farm and its owner, an R. J. Cook. We can identify this person as Richard James Cook, who like his father before him had operated Lodge Farm, which of course we know has a long connection with Linford House. The record is dated 1974-76, so we can presume that Linford House was finally demolished toward the end of the period. For more on the Cook family, see the history of Lodge Farm on this website.

The property meanwhile had been sold in 1961 for £2,350, though the brief note carried in the Wolverton Express of September 8th, makes no mention of the buyer. The house and grounds appear on the 1968 O.S map, but the 1972 O.S map has a different story to tell. Church Farm Crescent and it’s houses has been built; the farmhouse has at least for then survived, though now renamed to Crescent Farm. Click here to view the 1972 O.S map.

One final piece of the story remains, held by the Buckinghamshire Record Office. These are copies of the conveyancing records for the purchase of the house by the Milton Keynes Development Corporation (D-MKDC/9/1/59), naming Crescent Farm and its owner, an R. J. Cook. We can identify this person as Richard James Cook, who like his father before him had operated Lodge Farm, which of course we know has a long connection with Linford House. The record is dated 1974-76, so we can presume that Linford House was finally demolished toward the end of the period. For more on the Cook family, see the history of Lodge Farm on this website.