The Nags Head Pub, Great Linford

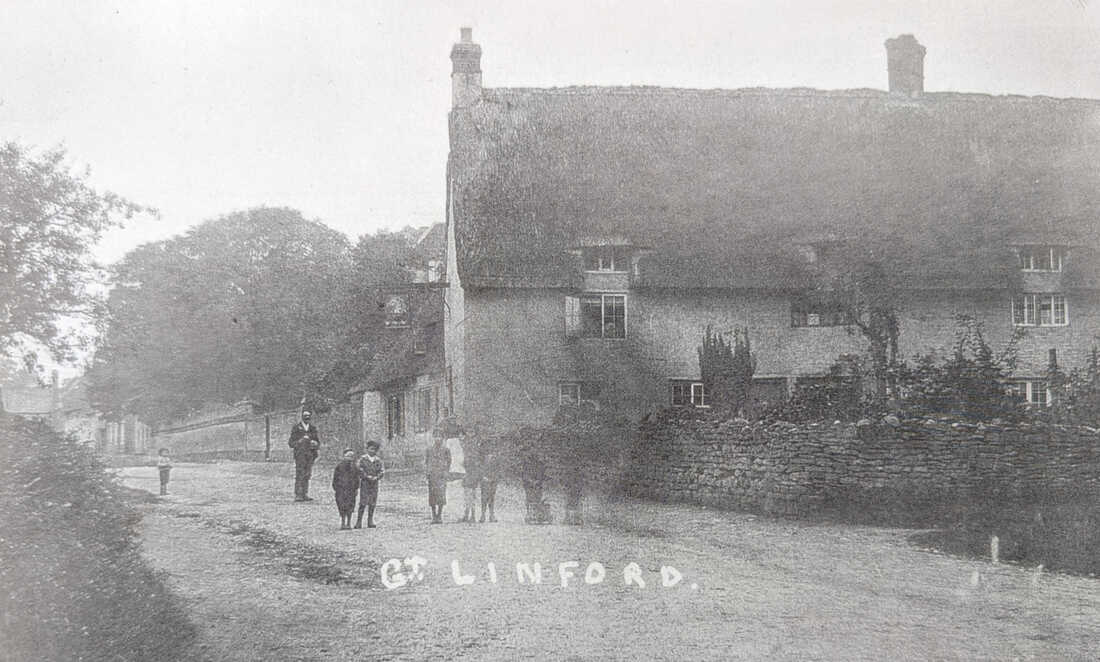

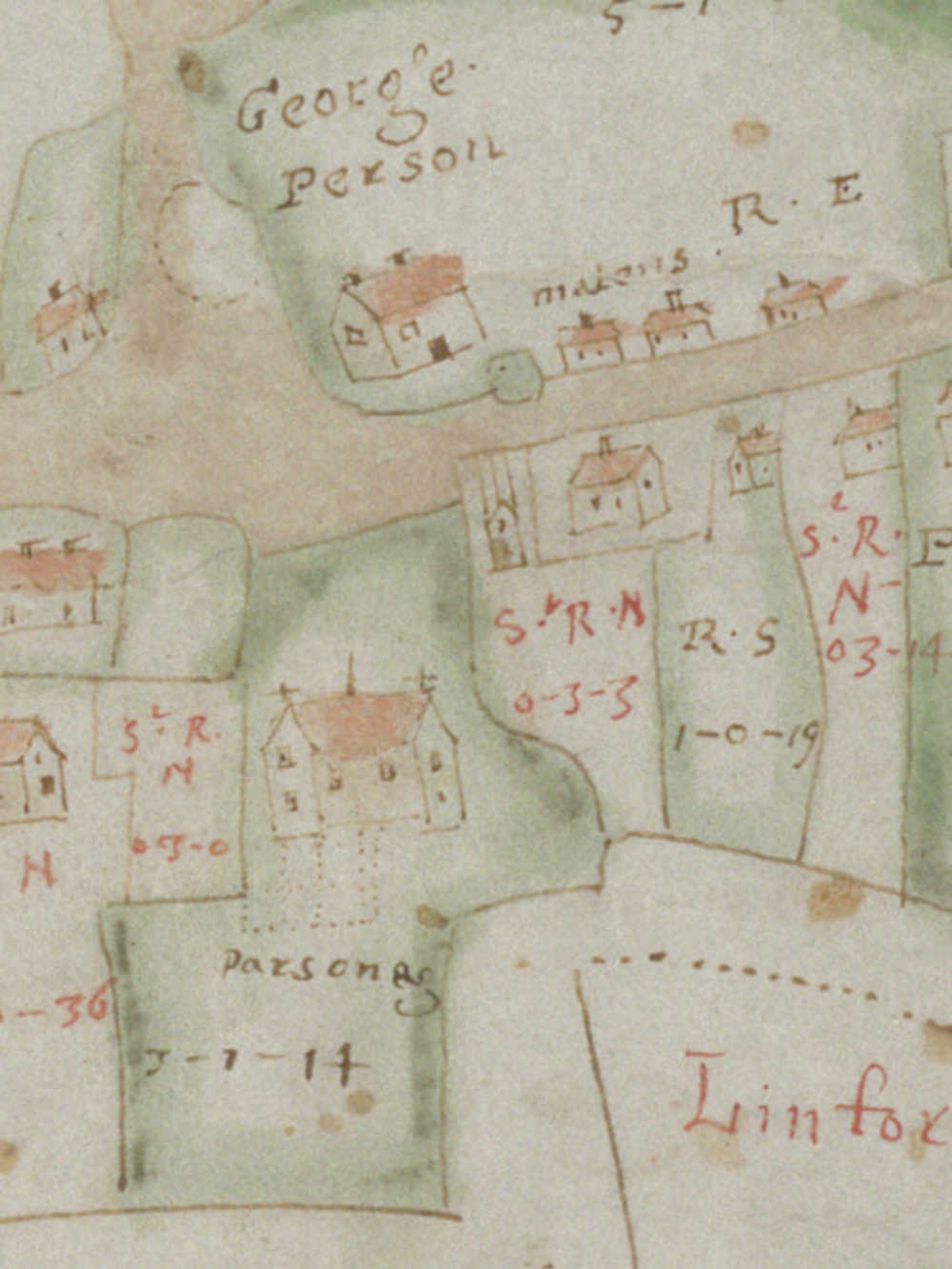

The Nags Head occupies pride of place on the High Street, just before the main gates to Great Linford Manor Park, and a stone’s throw from the Old Rectory, or Parsonage, as it is has also been known. Who knows, it might well have been that upon particularly boisterous nights, the stern reproaching gaze of the rector was directed toward the establishment, unless of course he enjoyed a cheeky tipple himself. An estate map of the village drawn up in 1641 (Buckinghamshire Archives MaR/26) shows a building on the same spot (as near as can be estimated) now occupied by The Nags Head, but we have no evidence it was then a public house. Regardless, if the current Nags Head retains within its fabric any of the structure of 1641, then it may well be one of the oldest buildings in the village.

On the extract below, we can see a building (toward the centre of the map) occupying what we can reasonably take to be the present location of The Nags Head, though as can be seen, it is depicted as a thin rectangular building on an east-west axis. We cannot of course be sure how accurate the map maker was, although the Parsonage is reasonably recognisable, so perhaps we can presume that the depictions have some basis in reality. The notation S.R.N refers to the owner of the house and land, Sir Richard Napier, with the figure of 0-3-3 indicating the size of the plot, in this case, zero acres, three roods and three perches, the latter two being old measurements for land.

On the extract below, we can see a building (toward the centre of the map) occupying what we can reasonably take to be the present location of The Nags Head, though as can be seen, it is depicted as a thin rectangular building on an east-west axis. We cannot of course be sure how accurate the map maker was, although the Parsonage is reasonably recognisable, so perhaps we can presume that the depictions have some basis in reality. The notation S.R.N refers to the owner of the house and land, Sir Richard Napier, with the figure of 0-3-3 indicating the size of the plot, in this case, zero acres, three roods and three perches, the latter two being old measurements for land.

The 1678 estate map of the parish (Buckinghamshire Archives D-BAS/Maps/50) is not as detailed and is drawn on a different orientation, but we can again see a small building that can be equated with The Nags Head.

The book A Guide to the Historic Buildings of Milton Keynes (1986, Paul Woodfield, Milton Keynes Development Corporation) provides the following description of the pub, which it should be noted, proposes a build date toward the end of the 1600s.

An Inn, later 17th century, of colourwashed stone with a thatched roof. It has two storeys and an attic still lit by the original 17th century wood mullioned and diamond paned windows. The other windows have been replaced in the 19th and 20th centuries. The building is of four bays, with a rear wing, also thatched, extending back along the High Street.

The inference that the building served as an Inn in the late 17th century is arguably problematic, as the first reference to a pub called The Nags Head in Great Linford is dated 1792, contained in a ledger of licenses granted between 1754 and 1823 to publicans in the Newport Three Hundred, the name for the administrative region that included the parish (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X_423/9.) Pubs can and do change name, but the evidence presented in this document is persuasive that The Nags Head was established as a new enterprise within the village in 1792.

We have some interesting pub names in the parish for which we can make reasonable suppositions as to origin of their signs (see The White Horse and The Six Bells) but the commonly held idea behind the reason for naming a pub The Nags Head falls rather short in the case of Great Linford, as it would only really make sense if the village had a beach. The story goes that a pub named The Nags Head relates to the practice of providing an all-clear signal to pirates wishing to come ashore at night, which was achieved by hanging a lantern around the neck of docile horse, who was then led back and forth along the shore. Of course, we have no way of knowing if this was in the mind of the landlord when he (or the landowner) decided on this sign (it seems on balance unlikely), but we do know the pub has been under continuous operation under this name from its very earliest days.

We have some interesting pub names in the parish for which we can make reasonable suppositions as to origin of their signs (see The White Horse and The Six Bells) but the commonly held idea behind the reason for naming a pub The Nags Head falls rather short in the case of Great Linford, as it would only really make sense if the village had a beach. The story goes that a pub named The Nags Head relates to the practice of providing an all-clear signal to pirates wishing to come ashore at night, which was achieved by hanging a lantern around the neck of docile horse, who was then led back and forth along the shore. Of course, we have no way of knowing if this was in the mind of the landlord when he (or the landowner) decided on this sign (it seems on balance unlikely), but we do know the pub has been under continuous operation under this name from its very earliest days.

James and Mary Hitchen

The ledger entry for license holders in 1792 names the publican of The Nags Head as James Hitchin, but we do have some evidence for his employment in the village before he took on the pub, as in 1788 he appears to have been a gamekeeper for Mrs Frances Uthwatt of the manor, as a James Hitchin is named amongst a list of appointments carried in the Northampton Mercury of November 8th. He continued in the role until at least the following year, as the Northampton Mercury reports upon a repeat appointment in 1789.

We do not have a baptism for James in Great Linford, but we can push his presence in the parish back further, thanks to a record of his marriage to a Mary Shirley. Generally, tradition dictated that a bride was married in her home parish, and this is borne out by the discovery of a marriage at Dallington in Northamptonshire, that occurred on January 20th, 1773, between James Hitchen of Great Linford and Mary Shirley of the aforesaid Dallington. The name Hitchen (or any variant spelling) does not otherwise feature in the parish records of Dallington, so we must presume that James was born and raised elsewhere. The same can be said for Mary, so she too also must have hailed originally from a different parish.

Whatever their origins, the couple decided to make Great Linford their family home, with seven children baptised at St. Andrews between 1773 and 1789. The spelling of James’s surname is predominantly written as Hitchin in the license records, Hitchen in the parish records, but there can be little doubt that they are one and the same person. This variable spelling plagues all the records that can be found for James and in general confused spellings are not at all unusual for the time. The children were, Ann (1774), Frances (1776), George (1778), Mary (1779), James (1782), Elizabeth (1786) and William, born in 1789.

We do not know where these children were born in the village or wider parish; it could have been the dwelling that would become The Nags Head, but baptism records at this time were not standardised, and additional details if any were generally added at the whim of the clerk, so there is simply no way of knowing. The same goes for burial records, though one additional child can be identified, an Edward Hitchen, buried October 1st, 1783, with the observation that he had been privately baptised. This tells us something tragic, as the phrase is applied when a child is considered too sick to be brought to church. We can infer then that Edward was a newborn and was either baptised by a priest who visited the house, or even by a midwife, or as the rules had it, anyone else in an emergency who was themselves baptised.

On March 15th, 1794, James placed a notice in the Northampton Mercury, offering to “be lett or sold, at Great Linford, in the county of Bucks, an Ass and a Foal four days old, Enquire of Mr Hitchin, at the Nag’s Head, at Great Linford, aforesaid.” This though represents the only reference found to James in newspapers. He passed away at Great Linford in 1799 and was buried at in St. Andrews churchyard on May 1st. Turning back to the licensing records, we find that his widow Mary then becomes the publican of The Nags Head, continuing to appear each year in the register until 1805. But in 1806, The Nags Head abruptly drops from sight, and no-one is listed again as publican until 1812.

Exactly what happened to the pub during this period is uncertain. The passing of Mary Hitchen is recorded in the parish burial records, with her burial taking place on May 9th, 1809, but presumably she had already either elected to surrender the license or was otherwise removed circa 1806. We have no firm evidence for her age, but we can make an educated guess that she was in her late 50s when she died, so retirement due to old age does not seem a likely explanation, though of course all manner of illness could have afflicted her.

Does all this mean Mary had vacated the premises? Very possibly so. Intriguingly, we have an indenture drawn up by the Uthwatts in 1808 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X_2228), which includes a reference to The Nags Head, but tellingly leaves blank the area where the name of the occupier should appear. Given the otherwise meticulous detail in this document, this surely deliberate omission strongly implies that the pub was then lying vacant.

We do not have a baptism for James in Great Linford, but we can push his presence in the parish back further, thanks to a record of his marriage to a Mary Shirley. Generally, tradition dictated that a bride was married in her home parish, and this is borne out by the discovery of a marriage at Dallington in Northamptonshire, that occurred on January 20th, 1773, between James Hitchen of Great Linford and Mary Shirley of the aforesaid Dallington. The name Hitchen (or any variant spelling) does not otherwise feature in the parish records of Dallington, so we must presume that James was born and raised elsewhere. The same can be said for Mary, so she too also must have hailed originally from a different parish.

Whatever their origins, the couple decided to make Great Linford their family home, with seven children baptised at St. Andrews between 1773 and 1789. The spelling of James’s surname is predominantly written as Hitchin in the license records, Hitchen in the parish records, but there can be little doubt that they are one and the same person. This variable spelling plagues all the records that can be found for James and in general confused spellings are not at all unusual for the time. The children were, Ann (1774), Frances (1776), George (1778), Mary (1779), James (1782), Elizabeth (1786) and William, born in 1789.

We do not know where these children were born in the village or wider parish; it could have been the dwelling that would become The Nags Head, but baptism records at this time were not standardised, and additional details if any were generally added at the whim of the clerk, so there is simply no way of knowing. The same goes for burial records, though one additional child can be identified, an Edward Hitchen, buried October 1st, 1783, with the observation that he had been privately baptised. This tells us something tragic, as the phrase is applied when a child is considered too sick to be brought to church. We can infer then that Edward was a newborn and was either baptised by a priest who visited the house, or even by a midwife, or as the rules had it, anyone else in an emergency who was themselves baptised.

On March 15th, 1794, James placed a notice in the Northampton Mercury, offering to “be lett or sold, at Great Linford, in the county of Bucks, an Ass and a Foal four days old, Enquire of Mr Hitchin, at the Nag’s Head, at Great Linford, aforesaid.” This though represents the only reference found to James in newspapers. He passed away at Great Linford in 1799 and was buried at in St. Andrews churchyard on May 1st. Turning back to the licensing records, we find that his widow Mary then becomes the publican of The Nags Head, continuing to appear each year in the register until 1805. But in 1806, The Nags Head abruptly drops from sight, and no-one is listed again as publican until 1812.

Exactly what happened to the pub during this period is uncertain. The passing of Mary Hitchen is recorded in the parish burial records, with her burial taking place on May 9th, 1809, but presumably she had already either elected to surrender the license or was otherwise removed circa 1806. We have no firm evidence for her age, but we can make an educated guess that she was in her late 50s when she died, so retirement due to old age does not seem a likely explanation, though of course all manner of illness could have afflicted her.

Does all this mean Mary had vacated the premises? Very possibly so. Intriguingly, we have an indenture drawn up by the Uthwatts in 1808 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-X_2228), which includes a reference to The Nags Head, but tellingly leaves blank the area where the name of the occupier should appear. Given the otherwise meticulous detail in this document, this surely deliberate omission strongly implies that the pub was then lying vacant.

The ownership of the Nags Head

The question arises as to who owned The Nags Head; it certainly was not the Hitchens, but we know from the estate map of 1641 that it was Sir Richard Napier, the Lord of Great Linford manor, who had title to the land and the house that then stood upon it. We can confidently take it to be the case that the land and any houses built upon it would have passed by inheritance to a long line of Lords, from the Napiers, through to the Prichards and finally to the Uthwatts. The indenture of 1808 makes clear that it was Henry Uthwatt who owned the pub, however, he may not have owned it for much longer. In 1816, an advertisement was placed in the Northampton Mercury of December 28th, for the sale of a capital dwelling house, brewery and malting in Newport Pagnell, along with 19 public houses. One of the pubs to be auctioned off was The Nags Head, offered as a leasehold with two years to run.

Exactly what this implies is open to interpretation. Had the brewery leased the pub from the Uthwatts, or did the lease refer to an agreement between the brewery and its tenant, in which case we might speculate that the brewery had purchased the pub lock, stock and barrel. As to the brewery, its origins can be traced back to the 1780s, when the business was established by a Thomas Meacher, though by 1810 it had gone bankrupt and was sold. New owners Thomas Warriner Baseley and William Stapleton did their best to build up the business, accumulating a portfolio of 20 freehold and leasehold pubs, but by 1815 they too were finding conditions difficult, and the brewery and its pubs were put up for sale. After several abortive attempts to dispose of the business, Baseley and Stapleton were themselves declared bankrupt in January 1816, but once again the business proved difficult to sell. Finally in January 1817, having failed to sell the business in its entirety, the brewery and pubs were put up for sale individually, but even this failed to go smoothly, with proceedings at the High Court of Chancery in London delaying the sale until March. The brewery was eventually purchased by Joseph Parsons, a brewer from St. Albans and his business partner, a Doctor from Newport Pagnell named John Rogers. Rogers and Parson also had an interest in the Wharf at Great Linford.

Exactly what had happened to the ownership of The Nags Head during this period is clearly somewhat uncertain, but in 1872, the Clerk of the Peace had ordered the Chief Constable of the county to compile a list of all the pubs in Buckinghamshire, which he duly returned. This tells us that the Uthwatts had allegedly held the ownership of the pub for “over 50 years”, a frustratingly vague figure that does nothing to clarify matters, but does tell us that they were long term owners of the pub.

Exactly what this implies is open to interpretation. Had the brewery leased the pub from the Uthwatts, or did the lease refer to an agreement between the brewery and its tenant, in which case we might speculate that the brewery had purchased the pub lock, stock and barrel. As to the brewery, its origins can be traced back to the 1780s, when the business was established by a Thomas Meacher, though by 1810 it had gone bankrupt and was sold. New owners Thomas Warriner Baseley and William Stapleton did their best to build up the business, accumulating a portfolio of 20 freehold and leasehold pubs, but by 1815 they too were finding conditions difficult, and the brewery and its pubs were put up for sale. After several abortive attempts to dispose of the business, Baseley and Stapleton were themselves declared bankrupt in January 1816, but once again the business proved difficult to sell. Finally in January 1817, having failed to sell the business in its entirety, the brewery and pubs were put up for sale individually, but even this failed to go smoothly, with proceedings at the High Court of Chancery in London delaying the sale until March. The brewery was eventually purchased by Joseph Parsons, a brewer from St. Albans and his business partner, a Doctor from Newport Pagnell named John Rogers. Rogers and Parson also had an interest in the Wharf at Great Linford.

Exactly what had happened to the ownership of The Nags Head during this period is clearly somewhat uncertain, but in 1872, the Clerk of the Peace had ordered the Chief Constable of the county to compile a list of all the pubs in Buckinghamshire, which he duly returned. This tells us that the Uthwatts had allegedly held the ownership of the pub for “over 50 years”, a frustratingly vague figure that does nothing to clarify matters, but does tell us that they were long term owners of the pub.

James and Mary Clare

While all this property speculation was going on, the pub had reopened to business, and in a manner of speaking we can continue to connect the Hitchens to the pub via Mary Hitchen’s namesake daughter, who had been born in 1779. On November 18th, 1802, Mary was married at Great Linford to a James Clare and whom do we find as the landlord of a revived Nags Head in 1812, but none other than James.

The origins of Clares are presently uncertain, but the couple had at least six children at Great Linford, Ann in 1806, Mary in 1808, Frances in 1809, Elizabeth in 1813, John in 1815 and William in 1819; the latter three at least, presumably born at The Nags Head. James Clare continued as the landlord until his untimely death in September of 1821, aged just 42 years old. Mary followed just a few years later in December of 1824, aged 45. Both were buried at Great Linford.

This double tragedy raises the sad question of what became of their orphans, many still young children. We can trace several into adult life, including John, who in 1828 was apprenticed aged 13 (Buckinghamshire Archives PR_131/25/63/5) to a Newport Pagnell tailor named William Burgess. Notably, the apprenticeship was arranged by the charity endowed by the former Lord of the Manor Sir William Prichard. This does suggest that at least one of the Clare children found refuge in the locality, and certainly there were other members of the Hitchen family in the village who could have put a roof over their heads. John appears to have successfully completed his apprenticeship and moved to London, where he continued to work as a tailor. His brother William also moved to the capital, where he forged a career as a butler. Indeed, London seems to have been the place with streets metaphorically paved with gold for the Clare orphans, as Frances was married there to an omnibus driver named Edward Lankshear.

The origins of Clares are presently uncertain, but the couple had at least six children at Great Linford, Ann in 1806, Mary in 1808, Frances in 1809, Elizabeth in 1813, John in 1815 and William in 1819; the latter three at least, presumably born at The Nags Head. James Clare continued as the landlord until his untimely death in September of 1821, aged just 42 years old. Mary followed just a few years later in December of 1824, aged 45. Both were buried at Great Linford.

This double tragedy raises the sad question of what became of their orphans, many still young children. We can trace several into adult life, including John, who in 1828 was apprenticed aged 13 (Buckinghamshire Archives PR_131/25/63/5) to a Newport Pagnell tailor named William Burgess. Notably, the apprenticeship was arranged by the charity endowed by the former Lord of the Manor Sir William Prichard. This does suggest that at least one of the Clare children found refuge in the locality, and certainly there were other members of the Hitchen family in the village who could have put a roof over their heads. John appears to have successfully completed his apprenticeship and moved to London, where he continued to work as a tailor. His brother William also moved to the capital, where he forged a career as a butler. Indeed, London seems to have been the place with streets metaphorically paved with gold for the Clare orphans, as Frances was married there to an omnibus driver named Edward Lankshear.

Richard and Sarah Bacchus

Though she had outlived her husband by several years, Mary Clare was not afforded the opportunity to follow in her late husband’s footsteps, as the 1822 license record provides a new landlord at The Nags Head, Richard Bacchus. That a pub should have as its landlord a man who shares his surname with the Greek God of wine can be considered serendipitous in the extreme, though the Bacchus family had actually come from farming stock, Richard and his brother William having held the tenancy to Lodge Farm in the parish.

Richard’s origins are not entirely clear, but a plausible baptism has been identified in 1778 at Hanslope in Buckinghamshire. His wife Sarah Pinkard was born in 1784 at Great Linford and the couple were married in the village on August 7th, 1806. They had at least nine children together: William (1809), Edmund (1812), twins Martha and Ann (1815), Sarah (1816), Jane (1819), twins Philip and Thomas (1822) and Harriett in 1823. We can infer that Philip, Thomas and Harriett were likely born at The Nags Head.

The licencing records cease in 1827, still showing Richard as the landlord. A bound ledger dated that same year and now held at Bedfordshire Archives (Z 1043/1) contains a tally of debts outstanding to John & Joseph Morris Esqs., brewers of Ampthill, including a note of a debt owed by Richard. The same ledger also contains an outstanding debt for the several-years-deceased Mary Clare. Both were recorded in the bad debtor’s column, with Richard owning £4, one shilling and eight pence, while Mary (recorded as Widow Clare) owed £72, two shilling and seven pence, an eye-watering sum in modern terms equivalent to approximately £5000. This of course was very much a bad debt, as the brewery’s only hope of recovery was to pursue her executors. That the debt was still on their books several years after her death is telling, but perhaps we can further speculate that it had been debt that drove Mary to throw in the towel. The further presumption of course is that John & Joseph Morris had been supplying The Nags Head with beer and/or spirits.

A Richard Bacchus was buried at Great Linford on October 1st, 1832, aged 53, who we can plausibly presume to be the same Richard running The Nags Head. He was succeeded by his widow Sarah. We know that Sarah was still the publican circa 1840 as we have several useful new records to refer to, and for the first time can place the pub firmly on a map.

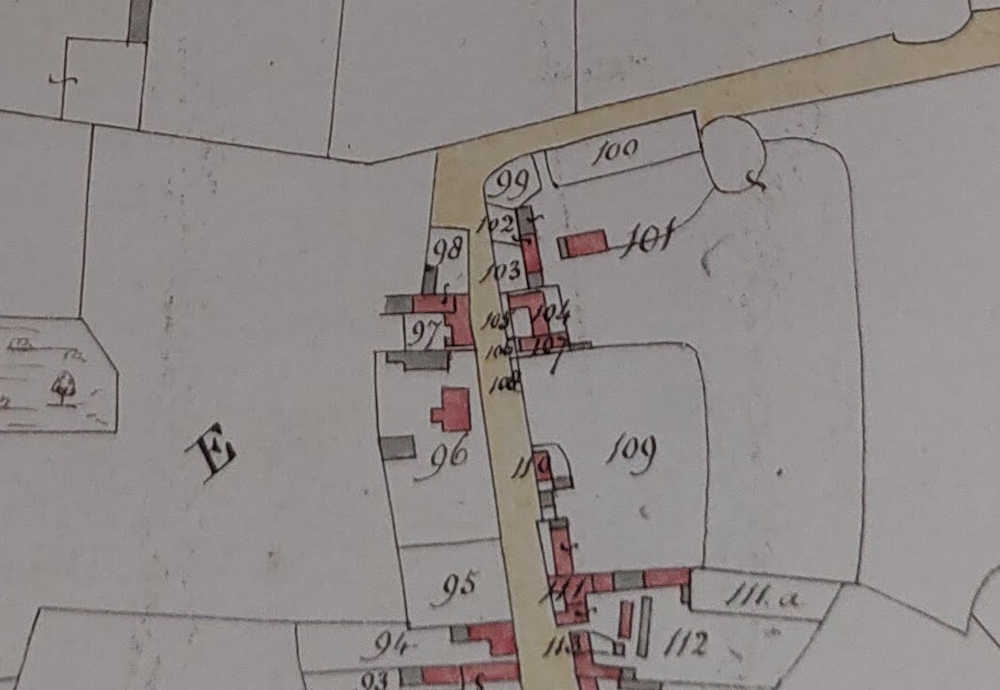

The first of these documents is a tithe map for the village, drawn up in 1840. The map (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255), along with a directory of owners and occupants of land and dwellings was created in order to assign a monetary value on the traditional tithe payments that were required to be paid to the church, typically 10% of a person’s agricultural output. The tithe taxes had become increasingly complicated to administer as land was bought and sold, often changing use, but retaining the obligation to pay a tithe. Each building or parcel of land on the map was indexed, and a number assigned, not to be confused with modern house numbers, which were only introduced to the High Street sometime around the 1950s.

The tithe map is an illuminating document, as it shows that The Nags Head was considerably smaller in 1840 than it is today. The pub occupied only that part of the present-day structure that fronts directly upon the High Street, identified as number 97 on the map. The adjoining dwelling labelled as Number 98 (which includes within its curtilage the outbuilding still in situ today) is described as “cottages and gardens” in the occupation of William Barker & George Keedle.

What is now the outside seating area for The Nags Head were gardens; there certainly still appears to be a garden visible in the photograph reproduced at the beginning of this page. The areas on the map coloured in red are dwellings, those in grey are outbuildings. The tithe map index also tells us that the land and dwellings associated with The Nags Head were owned by Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, the then lord of the manor.

Richard’s origins are not entirely clear, but a plausible baptism has been identified in 1778 at Hanslope in Buckinghamshire. His wife Sarah Pinkard was born in 1784 at Great Linford and the couple were married in the village on August 7th, 1806. They had at least nine children together: William (1809), Edmund (1812), twins Martha and Ann (1815), Sarah (1816), Jane (1819), twins Philip and Thomas (1822) and Harriett in 1823. We can infer that Philip, Thomas and Harriett were likely born at The Nags Head.

The licencing records cease in 1827, still showing Richard as the landlord. A bound ledger dated that same year and now held at Bedfordshire Archives (Z 1043/1) contains a tally of debts outstanding to John & Joseph Morris Esqs., brewers of Ampthill, including a note of a debt owed by Richard. The same ledger also contains an outstanding debt for the several-years-deceased Mary Clare. Both were recorded in the bad debtor’s column, with Richard owning £4, one shilling and eight pence, while Mary (recorded as Widow Clare) owed £72, two shilling and seven pence, an eye-watering sum in modern terms equivalent to approximately £5000. This of course was very much a bad debt, as the brewery’s only hope of recovery was to pursue her executors. That the debt was still on their books several years after her death is telling, but perhaps we can further speculate that it had been debt that drove Mary to throw in the towel. The further presumption of course is that John & Joseph Morris had been supplying The Nags Head with beer and/or spirits.

A Richard Bacchus was buried at Great Linford on October 1st, 1832, aged 53, who we can plausibly presume to be the same Richard running The Nags Head. He was succeeded by his widow Sarah. We know that Sarah was still the publican circa 1840 as we have several useful new records to refer to, and for the first time can place the pub firmly on a map.

The first of these documents is a tithe map for the village, drawn up in 1840. The map (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255), along with a directory of owners and occupants of land and dwellings was created in order to assign a monetary value on the traditional tithe payments that were required to be paid to the church, typically 10% of a person’s agricultural output. The tithe taxes had become increasingly complicated to administer as land was bought and sold, often changing use, but retaining the obligation to pay a tithe. Each building or parcel of land on the map was indexed, and a number assigned, not to be confused with modern house numbers, which were only introduced to the High Street sometime around the 1950s.

The tithe map is an illuminating document, as it shows that The Nags Head was considerably smaller in 1840 than it is today. The pub occupied only that part of the present-day structure that fronts directly upon the High Street, identified as number 97 on the map. The adjoining dwelling labelled as Number 98 (which includes within its curtilage the outbuilding still in situ today) is described as “cottages and gardens” in the occupation of William Barker & George Keedle.

What is now the outside seating area for The Nags Head were gardens; there certainly still appears to be a garden visible in the photograph reproduced at the beginning of this page. The areas on the map coloured in red are dwellings, those in grey are outbuildings. The tithe map index also tells us that the land and dwellings associated with The Nags Head were owned by Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, the then lord of the manor.

In 1841 the first national census was conducted, and we can cross-reference this with the tithe map to learn something more of the circumstances of William and George. William we can see is a 48-year-old carpenter, with a wife named Mary and six children ranging in age from six to 19. George Keedle on the other hand is a single 70-year-old agricultural labourer.

The 1841 census also tells is that Sarah Bacchus is still the landlady of The Nags Head, occupying the pub with her teenage daughter Harriot. The 1841 census is rather sparse on detail, so does not include any street or place names, but the next census in 1851 explicitly names The Nags Head as the abode of Sarah Bacchus, now alone except for a lodger named David Walters, who described himself as a gardener. We can also refer to trade directories, finding Sarah named as a Beer retailer in a Post Office trade directory of 1847.

In what might be reasonably dismissed as an error in reporting, the Bucks Chronicle and Bucks Gazette of August 23rd, 1851, provides a summary of applicants to Newport Pagnell Police Court on the occasion of a general licensing day. Unexpectantly, Sarah Bacchus is named as the publican of the Swan Inn at Great Linford. Was this a mistake, or did The Nags Head briefly go by this different name? Certainly, it is named as The Nags Head in the Kelly’s Trade Directory of 1854. Notably there was a Swan Inn at Newport Pagnell, so the odds of an error in the reporting seems high.

Sarah did have at least one run-in with the law, convicted of being in possession of an unjust measure (was she intentionally short-changing her patrons?) on January 11th, 1859, for which she was fined 14 shillings and six pence. But regardless of this blemish upon her character, Sarah was clearly a redoubtable woman, continuing to run the pub single-handily well into her 70s; it appears she even found the time to take on some other duties, as a Post Office Appointment Book entry records that a Sarah Bacchus was employed on June 30th, 1852. We do not know what her duties were, and it may not have been a lasting appointment, as a James Bird is recorded in the Musson & Craven’s trade directory of 1853 as the village postmaster, and for many years thereafter in other directories.

The Nags Head was sometimes a venue for sales of items like properties and produce, with one such sale announced in the Bucks Herald of January 16th, 1858. The sale was for about “400 capital ELM, ASH and POPULAR timber trees now standing on the Great Linford Estate, on farms in the occupation of Mrs. Jarvis and Messrs Johnson.” The sale was to take place on Thursday January 28th, at one o’clock.

Sarah is alone at The Nags Head in the 1861 census and still listed as the publican in 1864, appearing as such in the Post Office directory for that year. She passed away aged 80 at Great Linford on May 1st, 1865, her death certificate revealing that the cause was “decay of nature”, so essentially old age. Of passing note, there appears to be no entry for a burial for Sarah at St. Andrew’s church, which is certainly strange given her long connection with Great Linford, but nor has a place of burial elsewhere become apparent.

The 1841 census also tells is that Sarah Bacchus is still the landlady of The Nags Head, occupying the pub with her teenage daughter Harriot. The 1841 census is rather sparse on detail, so does not include any street or place names, but the next census in 1851 explicitly names The Nags Head as the abode of Sarah Bacchus, now alone except for a lodger named David Walters, who described himself as a gardener. We can also refer to trade directories, finding Sarah named as a Beer retailer in a Post Office trade directory of 1847.

In what might be reasonably dismissed as an error in reporting, the Bucks Chronicle and Bucks Gazette of August 23rd, 1851, provides a summary of applicants to Newport Pagnell Police Court on the occasion of a general licensing day. Unexpectantly, Sarah Bacchus is named as the publican of the Swan Inn at Great Linford. Was this a mistake, or did The Nags Head briefly go by this different name? Certainly, it is named as The Nags Head in the Kelly’s Trade Directory of 1854. Notably there was a Swan Inn at Newport Pagnell, so the odds of an error in the reporting seems high.

Sarah did have at least one run-in with the law, convicted of being in possession of an unjust measure (was she intentionally short-changing her patrons?) on January 11th, 1859, for which she was fined 14 shillings and six pence. But regardless of this blemish upon her character, Sarah was clearly a redoubtable woman, continuing to run the pub single-handily well into her 70s; it appears she even found the time to take on some other duties, as a Post Office Appointment Book entry records that a Sarah Bacchus was employed on June 30th, 1852. We do not know what her duties were, and it may not have been a lasting appointment, as a James Bird is recorded in the Musson & Craven’s trade directory of 1853 as the village postmaster, and for many years thereafter in other directories.

The Nags Head was sometimes a venue for sales of items like properties and produce, with one such sale announced in the Bucks Herald of January 16th, 1858. The sale was for about “400 capital ELM, ASH and POPULAR timber trees now standing on the Great Linford Estate, on farms in the occupation of Mrs. Jarvis and Messrs Johnson.” The sale was to take place on Thursday January 28th, at one o’clock.

Sarah is alone at The Nags Head in the 1861 census and still listed as the publican in 1864, appearing as such in the Post Office directory for that year. She passed away aged 80 at Great Linford on May 1st, 1865, her death certificate revealing that the cause was “decay of nature”, so essentially old age. Of passing note, there appears to be no entry for a burial for Sarah at St. Andrew’s church, which is certainly strange given her long connection with Great Linford, but nor has a place of burial elsewhere become apparent.

Thomas Rudkins

We next have a gap of several years in the records but can pick up the trail again in the 1869 Kelly’s trade directory. Here we find a new landlord for The Nags Head named Thomas Rudkins. Thomas had been baptised at Great Linford on August 9th, 1835, and we encounter him aged six on the 1841 census, with his father John (a Gardener) and mother Maria (nee Carr.)

Frustratingly, the 1840 Tithe map makes no mention of the family, so we cannot say where in the village they were then living, but when we find the family on the 1851 census, Thomas has followed in his father’s footsteps to become a gardener, and there are indications that he and his mother were residing in close proximity to The Nags Head, perhaps in the cottage previously identified as being a separate dwelling adjoining the pub. This intriguing possibility becomes all the more likely when we consider whom Thomas’s future wife was destined to be; he was married at Great Linford on August 22nd, 1866, to none other than Ann Bacchus, the daughter of Richard and Sarah Bacchus of The Nags Head!

Prior to this, the 1861 census finds Thomas living alone on the High Street, having swapped professions to become a railway labourer, a not untypical career progression due to the close proximity of Wolverton Railway Works. His marriage to Ann facilitated a further (and as it would happen, last) change of career, to that of publican. Notably, there was a considerable age difference between Thomas and Ann, with Thomas some 20 years her senior. They are named as husband and wife on the 1871 census, with Thomas recorded as 56 years old, and Ann as 36 years old; also present was Ann's daughter by an earlier marriage, Sarah Ann Warren. In 1857, Ann had married at Great Linford a tailer named John Warren, who subsequently became landlord of The Wharf Inn, but he passed away in 1865; earlier that same year John had been noted as present at the death of his mother-in-law, Sarah Bacchus.

The Nags Head was frequently chosen as a venue for coroner’s inquests in the event of deaths that had taken place in questionable circumstances, pubs being selected as they had the space to accommodate a jury. Local lore also has it that the outbuilding visible today from the beer garden was the village mortuary, and this seems corroborated by a sad story carried in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of April 26th, 1873, which notes that the body of young woman found drowned in the canal was “conveyed to the Nag’s Head” by cart.

Her name was Jane Nichols, and the coroner observed that this was a very unusual case and indeed that he had never seen a more remarkable one. Certainly the witnesses paint a picture of a young women with no obvious desire to do herself harm, yet there seem to be hints in her manner, words and deeds that something troubling had occurred. such that the conclusion reached was suicide, or in the vernacular of the time, felo de se. For a detailed account of this case and other coroner’s inquests, click here.

Ann Rudkins, nee Bacchus died aged 61 at Northampton on March 15th, 1875, though a notice of her death in the Northampton Mercury of March 20th, places her still resident at The Nags Head. Thomas died soon after on January 9th, 1876, at Great Linford. A newspaper notice in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of January 22nd asks all persons having a claim against Thomas Rudkin’s estate to contact William Warren (the brother of Ann's first husband John) at The Black Horse Inn. In fact, it was William Warren to whom the license of The Nags Head was subsequently transferred as executor of the estate. Almost exactly a year later, in the January 19th, 1877, edition of Croyden’s Weekly Standard, we find an advertisement telling us that William Warren had instructed an auctioneer to sell the entire household contents of The Nags Head. This was likely preparatory to the appointment of a new publican, with the transfer of the license from William Warren to William Scott being announced in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of March 17th.

Frustratingly, the 1840 Tithe map makes no mention of the family, so we cannot say where in the village they were then living, but when we find the family on the 1851 census, Thomas has followed in his father’s footsteps to become a gardener, and there are indications that he and his mother were residing in close proximity to The Nags Head, perhaps in the cottage previously identified as being a separate dwelling adjoining the pub. This intriguing possibility becomes all the more likely when we consider whom Thomas’s future wife was destined to be; he was married at Great Linford on August 22nd, 1866, to none other than Ann Bacchus, the daughter of Richard and Sarah Bacchus of The Nags Head!

Prior to this, the 1861 census finds Thomas living alone on the High Street, having swapped professions to become a railway labourer, a not untypical career progression due to the close proximity of Wolverton Railway Works. His marriage to Ann facilitated a further (and as it would happen, last) change of career, to that of publican. Notably, there was a considerable age difference between Thomas and Ann, with Thomas some 20 years her senior. They are named as husband and wife on the 1871 census, with Thomas recorded as 56 years old, and Ann as 36 years old; also present was Ann's daughter by an earlier marriage, Sarah Ann Warren. In 1857, Ann had married at Great Linford a tailer named John Warren, who subsequently became landlord of The Wharf Inn, but he passed away in 1865; earlier that same year John had been noted as present at the death of his mother-in-law, Sarah Bacchus.

The Nags Head was frequently chosen as a venue for coroner’s inquests in the event of deaths that had taken place in questionable circumstances, pubs being selected as they had the space to accommodate a jury. Local lore also has it that the outbuilding visible today from the beer garden was the village mortuary, and this seems corroborated by a sad story carried in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of April 26th, 1873, which notes that the body of young woman found drowned in the canal was “conveyed to the Nag’s Head” by cart.

Her name was Jane Nichols, and the coroner observed that this was a very unusual case and indeed that he had never seen a more remarkable one. Certainly the witnesses paint a picture of a young women with no obvious desire to do herself harm, yet there seem to be hints in her manner, words and deeds that something troubling had occurred. such that the conclusion reached was suicide, or in the vernacular of the time, felo de se. For a detailed account of this case and other coroner’s inquests, click here.

Ann Rudkins, nee Bacchus died aged 61 at Northampton on March 15th, 1875, though a notice of her death in the Northampton Mercury of March 20th, places her still resident at The Nags Head. Thomas died soon after on January 9th, 1876, at Great Linford. A newspaper notice in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of January 22nd asks all persons having a claim against Thomas Rudkin’s estate to contact William Warren (the brother of Ann's first husband John) at The Black Horse Inn. In fact, it was William Warren to whom the license of The Nags Head was subsequently transferred as executor of the estate. Almost exactly a year later, in the January 19th, 1877, edition of Croyden’s Weekly Standard, we find an advertisement telling us that William Warren had instructed an auctioneer to sell the entire household contents of The Nags Head. This was likely preparatory to the appointment of a new publican, with the transfer of the license from William Warren to William Scott being announced in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of March 17th.

William and Harriett Scott

Born circa 1809 in Whittlebury in Northamptonshire, William Scott seems to have had a rather varied career, from labourer, to groom and coachman. Along the way he married an Anne Judge at Whittlebury and in 1877 we find William listed in the Kelly’s trade directory as the landlord of The Nags Head. A coachman does not seem a great leap to publican, though we have no idea how he came to learn of the opportunity or apply for it. There is only one reference to be found in newspapers concurrent with William’s tenure (Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of February 28th, 1880), when the pub was the venue of a sale by auction of Oak and Elm trees. In fact, William’s tenure was to be a relatively brief one, as the Bucks Herald of January 29th, 1881, reports on the transfer of the license from William to Harriett Scott, his daughter and administrator, meaning that he had passed away.

William had himself already been widowed, possibly in 1872, but neither he nor his wife are recorded as been buried at Great Linford, not unheard of, as for instance sometimes people preferred to be buried in their home parish in a family plot. This is the case for William and Anne, who are to be found buried in the churchyard at Akeley in the Aylesbury Vale, where the couple were to be found on the 1871 census, and which is less than five miles from Whittlebury.

36-Year-old Harriett Scott and her 25-year-old sister Ann are at The Nags Head on the 1881 census, which was carried out on April 3rd. Harriett is described as the publican. She was shortly afterward married at Great Linford on June 13th, 1881, to a native of nearby Bradwell called William Claridge. As the head of the household, he promptly became the new publican of The Nags Head.

William had himself already been widowed, possibly in 1872, but neither he nor his wife are recorded as been buried at Great Linford, not unheard of, as for instance sometimes people preferred to be buried in their home parish in a family plot. This is the case for William and Anne, who are to be found buried in the churchyard at Akeley in the Aylesbury Vale, where the couple were to be found on the 1871 census, and which is less than five miles from Whittlebury.

36-Year-old Harriett Scott and her 25-year-old sister Ann are at The Nags Head on the 1881 census, which was carried out on April 3rd. Harriett is described as the publican. She was shortly afterward married at Great Linford on June 13th, 1881, to a native of nearby Bradwell called William Claridge. As the head of the household, he promptly became the new publican of The Nags Head.

William Claridge

We have little in the way of information relating to William Claridge’s tenure, though it was reported in Croydon's Weekly Standard of May 22nd, 1886, that the sanitary committee had received a complaint of leaking closets (toilets) at The Nags Head, the effluent of which had encroached upon the property of a Mr. J. Baily. A Joseph Baily was certainly a next-door neighbour to The Nags Head on the 1901 census, and given that when he died in 1909, he left an estate of over £12,000, we might reasonably suppose that the leak impinged upon Glebe House. Matters pertaining to waste arose again in 1904, with another complaint made, which usefully provides that the Aylesbury Brewing Company had been summonsed for failing to amend the drains at The Nags Head. This is the first indication since the 1840 Tithe Map of who might now be owning or leasing the pub, and indeed the Brewery History website provides that they were the owners in 1897, though some caution is merited, as primary evidence for this is presently lacking, and there is equal reason to think that the Uthwatts continued to hold title to the building.

Harriet had passed away on November 22nd, 1887, at Great Linford, aged 45; there is no record of any children from the marriage. However, William wasted no time in remarrying, to a Louisa Clare in the 2nd quarter of 1888. The surname Clare is one that begs attention, as of course a family of this name had previously leased the pub, but a connection has proved elusive, and we might just be dealing with coincidence. Louisa had been born in 1856 at Eggington in Bedfordshire and the couple had one daughter, Julia, in 1892. Cases of Scarlet Fever were considered noteworthy, and hence we find a report that eight-year-old Julia had caught the disease in November of 1900. This proved not to be fatal, and Julia lived to 45 years of age, passing away in Leighton Buzzard.

William Claridge was to be landlord of The Nags Head for a number of years and is last found recorded there on a census record in 1901. He seems not to have made a splash in the local newspapers, but we know that his mother Catherine passed away at Great Linford, aged 78 in 1899, presumably at The Nags Head. William himself died at 31 Dunville Road in Bedford, a fact recorded upon his burial at Great Linford on November 4th, 1902. His widow Louisa did not step into his shoes as landlady and was living in her home parish of Eggington by the time of the 1911 census. A notice in Croydon's Weekly Standard of March 15th, 1902, announces the transfer of the license to a Christopher John Pell.

Harriet had passed away on November 22nd, 1887, at Great Linford, aged 45; there is no record of any children from the marriage. However, William wasted no time in remarrying, to a Louisa Clare in the 2nd quarter of 1888. The surname Clare is one that begs attention, as of course a family of this name had previously leased the pub, but a connection has proved elusive, and we might just be dealing with coincidence. Louisa had been born in 1856 at Eggington in Bedfordshire and the couple had one daughter, Julia, in 1892. Cases of Scarlet Fever were considered noteworthy, and hence we find a report that eight-year-old Julia had caught the disease in November of 1900. This proved not to be fatal, and Julia lived to 45 years of age, passing away in Leighton Buzzard.

William Claridge was to be landlord of The Nags Head for a number of years and is last found recorded there on a census record in 1901. He seems not to have made a splash in the local newspapers, but we know that his mother Catherine passed away at Great Linford, aged 78 in 1899, presumably at The Nags Head. William himself died at 31 Dunville Road in Bedford, a fact recorded upon his burial at Great Linford on November 4th, 1902. His widow Louisa did not step into his shoes as landlady and was living in her home parish of Eggington by the time of the 1911 census. A notice in Croydon's Weekly Standard of March 15th, 1902, announces the transfer of the license to a Christopher John Pell.

Christopher John Pell

Christopher was another short-serving landlord of The Nags Head, and little has been found pertaining to his life and times at Great Linford; he is listed in Kelly’s Trade Directory of 1903, and we know that he and his wife Mary had a daughter Maud Rose and a son Harry Christopher. Records of their birth provide strong evidence that places the family in Milton in Northamptonshire prior to their move to Great Linford. As to his earlier life, we find five-month-old Christopher on the 1851 census at Collingtree, Northamptonshire, the child of John and Elizabeth. His father is described on Christopher’s baptism record as a publican and on the census as a licensed victualler, though Christopher grew up to be an agricultural labourer and shepherd. However, something must have rubbed off on him from his father, as prior to his taking on the Nags Head, Christopher was the publican of The Barley Mow at Cosgrove. Christopher is then the first landlord of The Nags Head we can say had verifiable prior experience in the trade.

William Haynes

The Northampton Mercury of October 15th, 1906, names Christopher's successor as William Haynes, and we can track his tenure through trade directories in 1907 and 1911. Very little has come to light as regards the life of William at Great Linford, though the 1911 census gives us some pertinent information; that he was born at Lathbury in 1858 and his career had progressed from agricultural labourer to “groom and gardener” to publican. Like William Scott before him, groom seems to have represented a steppingstone to running a pub. He had married Rose Caroline King in the Newport Pagnell registration district in 1881, and they had at least two children, a son Frederick and a daughter Edith, both born in Lathbury.

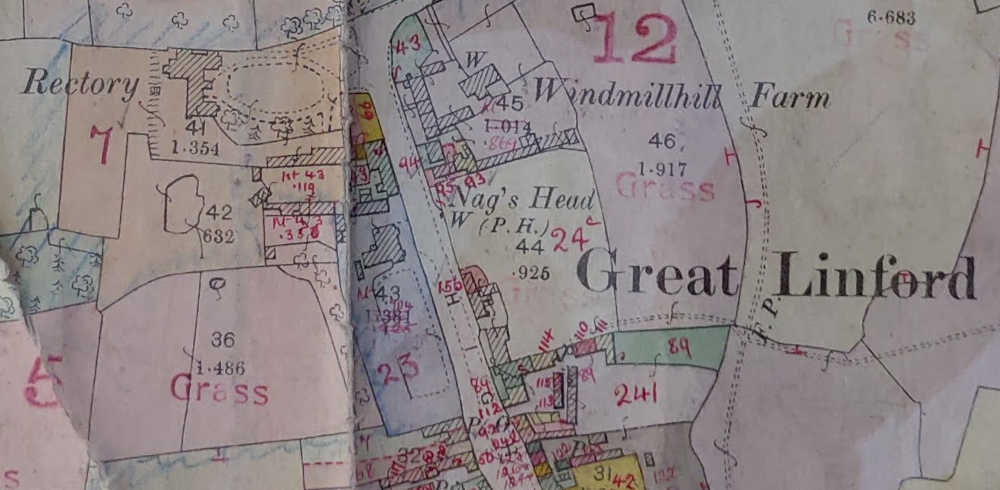

Another useful document can now be referenced in our history of The Nags Head, the 1910 valuation office survey map (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5.) This document, including a numbered map and an accompanying list of occupiers and owners, was the result of a survey carried out throughout the country to discover the taxable value of land and properties.

What seems apparent from the map is that The Nags Head (labelled now as 43) has absorbed more land into its curtilage than was seen on the 1840 Tithe Map, specifically a parcel of land on the opposite side of the street, now the location of the modern build Linford House. Unfortunately the map has been badly creased so some of the detail is obscured, but a substantial courtyard framed by buildings occupies the rear of the pub, those to the north marked as part of the Rectory; it is not entirely clear what other parts might have been included as part of the Nags Head. Certainly, the land now utilised as the pub’s beer garden (labelled as 66) is occupied by a William Mapley, who is also described in the accompanying index as the occupier of a cottage. The yellow shading (the meaning of which is unknown at present) does appear to encompass the separate building that abutted the pub in 1840, so it seems that the Nags Head had yet to assume its present L shaped layout. All the land and properties mentioned previously were in the ownership of the Lord of the Manor, William Uthwatt.

Another useful document can now be referenced in our history of The Nags Head, the 1910 valuation office survey map (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5.) This document, including a numbered map and an accompanying list of occupiers and owners, was the result of a survey carried out throughout the country to discover the taxable value of land and properties.

What seems apparent from the map is that The Nags Head (labelled now as 43) has absorbed more land into its curtilage than was seen on the 1840 Tithe Map, specifically a parcel of land on the opposite side of the street, now the location of the modern build Linford House. Unfortunately the map has been badly creased so some of the detail is obscured, but a substantial courtyard framed by buildings occupies the rear of the pub, those to the north marked as part of the Rectory; it is not entirely clear what other parts might have been included as part of the Nags Head. Certainly, the land now utilised as the pub’s beer garden (labelled as 66) is occupied by a William Mapley, who is also described in the accompanying index as the occupier of a cottage. The yellow shading (the meaning of which is unknown at present) does appear to encompass the separate building that abutted the pub in 1840, so it seems that the Nags Head had yet to assume its present L shaped layout. All the land and properties mentioned previously were in the ownership of the Lord of the Manor, William Uthwatt.

For reason's unknown, William chose to give up the pub, as we find him and his wife alive and well on the 1921 census for the parish, with William now working as a gardener. The 1921 census pages for Great Linford are rather deficient, as they make no reference to places of abode, so we cannot say where within the village the couple were then living. There is a plausible record of a death in 1922 for a William Haynes, and in 1939 we find his widow on Station Terrace, captured on the Register which was compiled on the eve of the Second World War.

Herbert Peach

As to who might have succeeded William Haynes and roughly when, a newspaper report in the North Bucks and County Observer dated May 24th, 1913, reports on a confrontation between local man Harry “Doggy” Robinson and the landlord of The Nags Head, named as Herbert Peach. It appears that Herbert was born in Buxton in Derbyshire in 1879, so would have been 34 when he had his altercation with Harry Robinson, nicknamed Doggy as he looked after the Bucks otter hound pack based in the manor grounds. The 1911 census reveals Herbert’s occupation as soldier, so we might surmise well able to deal with unruly pubgoers, though "Doggy" too had a military background. Herbert had joined the Northampton Regiment on May 2nd, 1895, when 18 years old, and his attestation document tells us that he weighed 134Ibs, was five feet, seven and 4/8 inches tall, had a fresh complexion, grey eyes and brown hair.

Herbert clearly intended the military as a career, as his records show he had voluntarily re-enlisted in 1906 with the aim of completing 21 years' service, but he was discharged at Devonport on August 23rd of 1912, on the grounds that he had been found medically unfit for further service. He had managed 17 years and 115 days. But it was to be an all too brief time in civvy street, as it was of course the eve of the first world war, and poor health or not, records indicate that Herbert was called back to duty.

Luckily, he survived the Great War, and a military pension record dated 1917 places him at Grove Cottages, Great Linford; this row of cottages has since been demolished. It seems he never returned to The Nags Head (except presumably as a patron), and indeed the 1922 census has him at Grange Farm, where his occupation is described as cowman. He had married in 1913 to a Sarah Keech from Newport Pagnell, and their first son Frank was born in 1915 at Great Linford, with two further sons born upon his return from the war.

Herbert clearly intended the military as a career, as his records show he had voluntarily re-enlisted in 1906 with the aim of completing 21 years' service, but he was discharged at Devonport on August 23rd of 1912, on the grounds that he had been found medically unfit for further service. He had managed 17 years and 115 days. But it was to be an all too brief time in civvy street, as it was of course the eve of the first world war, and poor health or not, records indicate that Herbert was called back to duty.

Luckily, he survived the Great War, and a military pension record dated 1917 places him at Grove Cottages, Great Linford; this row of cottages has since been demolished. It seems he never returned to The Nags Head (except presumably as a patron), and indeed the 1922 census has him at Grange Farm, where his occupation is described as cowman. He had married in 1913 to a Sarah Keech from Newport Pagnell, and their first son Frank was born in 1915 at Great Linford, with two further sons born upon his return from the war.

Stephen Walker

The Kelly’s directory of 1915 names the landlord of The Nags Head as Stephen Walker, and he proves one of the more enduring publicans in the village, with his name continuing to be listed in trade directories until 1931. Turning once again to the 1921 census, we find the following information. Stephen was born in 1878 at Roade in Northamptonshire. His wife Elizabeth had been born in New Bradwell in 1885, and together they had four daughters: Doris (1910), Maisie (1920), Sheila (1924) and Beryl in 1930. All but Doris was born at Great Linford, the rest presumably at The Nags Head. Stephen was that rarity in this history, a person with past pub experience; he is listed on the 1911 census as running the Square and Compasses at Great Shelford in Cambridgeshire, though prior to this he had been a bricklayer.

As to his time at The Nags Head, one might imagine that a pub would be mentioned in newspapers quite often for one reason or another, but Stephen appears to have run a harmonious establishment and there is not a hint of trouble or strife under his tenancy. The only exception (which we must presume to relate to an accident) is a case reported in the Northampton Mercury of December 5th, 1930, which provides that a, “Mr Steven Wilkes, aged 52 of the Nag’s Head, Great Linford, was admitted to Northampton General Hospital on Monday morning suffering from lacerations to the scalp.” The Wolverton Express carries the same story word for word, but no further clarification is forthcoming. There is no Steven Wilkes on the 1930 electoral roll for the village, nor the 1931 roll, but it is perhaps more than coincidence that going by his stated age of 52, Steven Wilkes shares the exact same year of birth as a Stephen Walker. The suspicion has to be that the newspaper has misreported the name, and it was Stephen Walker who suffered the mysteriously acquired lacerations to the scalp. The last sighting we have of Stephen and his family is on the 1931 electoral roll, on which we also find his wife Elizabeth and daughter Doris.

It does not seem that Stephen died at The Nags Head, as we find a plausible record for the family on the 1939 Register, now living at 2 Oxford Street in Wolverton, with two additional daughters added to the family. Stephen, now 61, has returned to his earlier trade of bricklayer.

As to his time at The Nags Head, one might imagine that a pub would be mentioned in newspapers quite often for one reason or another, but Stephen appears to have run a harmonious establishment and there is not a hint of trouble or strife under his tenancy. The only exception (which we must presume to relate to an accident) is a case reported in the Northampton Mercury of December 5th, 1930, which provides that a, “Mr Steven Wilkes, aged 52 of the Nag’s Head, Great Linford, was admitted to Northampton General Hospital on Monday morning suffering from lacerations to the scalp.” The Wolverton Express carries the same story word for word, but no further clarification is forthcoming. There is no Steven Wilkes on the 1930 electoral roll for the village, nor the 1931 roll, but it is perhaps more than coincidence that going by his stated age of 52, Steven Wilkes shares the exact same year of birth as a Stephen Walker. The suspicion has to be that the newspaper has misreported the name, and it was Stephen Walker who suffered the mysteriously acquired lacerations to the scalp. The last sighting we have of Stephen and his family is on the 1931 electoral roll, on which we also find his wife Elizabeth and daughter Doris.

It does not seem that Stephen died at The Nags Head, as we find a plausible record for the family on the 1939 Register, now living at 2 Oxford Street in Wolverton, with two additional daughters added to the family. Stephen, now 61, has returned to his earlier trade of bricklayer.

Thomas Ellis-Jones

Newspapers examined to date appear completely silent on the comings and goings at The Nags Head for the remainder of the decade, not even an unruly customer is reported upon, and it is not until the 1939 Kelly’s Trade Directory that we can avail ourselves of a new publican’s name, a Thomas Ellis-Jones. This is the last trade directory that has presently been found available to review, but we can cross-reference in the case of Thomas to the 1939 Register, where we find him and his wife at The Nags Head. Unfortunately, an error in the document obscures his date of birth, but his wife Muriel was born on February 16th, 1894, so we can presume both to be in their mid-forties. There are five other persons in the household, an Ethel Vallance, aged 42, a Cathleen Boorer, aged 41, and six-year-old Leslie Boorer, whom we can presume to be her daughter. The details of two other persons are redacted on the record for privacy reasons.

The 1939 Register reveals one other interesting detail, that there was a retired shepherd named Robert Harcourt living at “Nags Head Yard” with his wife and Elizabeth and three other persons, presumably their children, though as previously, the individual records have been redacted for privacy reasons. Looking back at the 1910 valuation office survey map, with its depiction of an extensive enclosed yard, we can presume this must be one and the same place.

1939 appears to have been a financially difficult time for The Nags Head, and pubs in general, as new business rates had been accessed due to a recent decision in the House of Lords, which meant that The Nags Head would see an increase in its yearly rates from £38 to £60. Perhaps this was a factor in the decision of Ellis-Jones to quit the license, as a notice in the Wolverton Express of November 15th of that year makes reference to a transfer of license. Though it makes no mention of the parties involved, one must presume it was Thomas Ellis-Jones who was quitting, and in fact we have some firm evidence to this effect.

The 1939 Register reveals one other interesting detail, that there was a retired shepherd named Robert Harcourt living at “Nags Head Yard” with his wife and Elizabeth and three other persons, presumably their children, though as previously, the individual records have been redacted for privacy reasons. Looking back at the 1910 valuation office survey map, with its depiction of an extensive enclosed yard, we can presume this must be one and the same place.

1939 appears to have been a financially difficult time for The Nags Head, and pubs in general, as new business rates had been accessed due to a recent decision in the House of Lords, which meant that The Nags Head would see an increase in its yearly rates from £38 to £60. Perhaps this was a factor in the decision of Ellis-Jones to quit the license, as a notice in the Wolverton Express of November 15th of that year makes reference to a transfer of license. Though it makes no mention of the parties involved, one must presume it was Thomas Ellis-Jones who was quitting, and in fact we have some firm evidence to this effect.

Frederick and Ida Sharp

An obituary in the Bucks Standard of April 17th, 1948, reports upon the death of a Mrs Ida Sharp, at Northampton Hospital after a short two-day illness. Ida was the wife of Frederick Henry Sharp, the landlord of The Nags Head. The article states that the couple came to the pub in 1940, so it seems entirely likely that they had succeeded Thomas Ellis-Jones. Further details to be gleaned from the article are that Ida hailed from Walsall in Staffordshire (though was actually born in Water Orton, Warwickshire), and was the daughter of Mr and Mrs David Palling. Ida had married Frederick Sharp in 1925, but they appear to have had no children. She was held “in high esteem” within the village, having become very involved in charitable endeavours, including for The Forces Fund and whist drives and other events in aid of local causes.

As to Frederick, he was born circa 1878 and prior to coming to Great Linford, may have been a housekeeper at Freemason’s Hall, the headquarters of the Freemasons in London. He also appears to have had a military background. We do not at present know if he remained as the landlord of The Nags Head after he was widowed, but it appears he died in the North Bucks region in 1958. The 1950s were a time when the Nags Head became closely associated with darts players in the village, with a succession of successful teams calling the pub home, so perhaps it was Frederick who was the driving force behind this. To learn more about darts at the Nags Head, click here.

Perhaps suggesting that Frederick had departed or died while landlord of The Nags Head, the Wolverton Express of March 14th, 1958, makes reference to the renewal of a license, though again omitting names. It also adds the interesting extra information that the renewal had been in doubt due to inadequate toilet facilities. At the previous licensing meeting, the chairman had made reference to several pubs (without specifically naming and shaming any) whose, “lavatory accommodation was appalling.” A representative of the Aylesbury Brewery Company attended the subsequent meeting, and though he stated that they did not own The Nags Head, advised the bench that they had negotiated a new lease and would therefore carry out the required alterations.

As to Frederick, he was born circa 1878 and prior to coming to Great Linford, may have been a housekeeper at Freemason’s Hall, the headquarters of the Freemasons in London. He also appears to have had a military background. We do not at present know if he remained as the landlord of The Nags Head after he was widowed, but it appears he died in the North Bucks region in 1958. The 1950s were a time when the Nags Head became closely associated with darts players in the village, with a succession of successful teams calling the pub home, so perhaps it was Frederick who was the driving force behind this. To learn more about darts at the Nags Head, click here.

Perhaps suggesting that Frederick had departed or died while landlord of The Nags Head, the Wolverton Express of March 14th, 1958, makes reference to the renewal of a license, though again omitting names. It also adds the interesting extra information that the renewal had been in doubt due to inadequate toilet facilities. At the previous licensing meeting, the chairman had made reference to several pubs (without specifically naming and shaming any) whose, “lavatory accommodation was appalling.” A representative of the Aylesbury Brewery Company attended the subsequent meeting, and though he stated that they did not own The Nags Head, advised the bench that they had negotiated a new lease and would therefore carry out the required alterations.

William Hartland

William Hartland is known to have been the licensee in the early 1960s, as he makes several appearances in the Wolverton Express newspaper. The first of these is an alarming story of a fire that had broken out on Sunday May 29th, 1960, at a poultry farm adjacent to The Nags Head. The “poultry house” involved in the fire was described as being located at Grey Gables, which proves to be the Rectory, as it was offered for sale in 1960 under that name. As described in the article carried in the Wolverton Express of June 3rd, “The blazing building joins their garden, and the houses nearby having thatched roofs, Mr and Mrs Hartland became very anxious.” William further added, “It was touch and go and but for prompt action our house would have gone.”

William was further named as one of the parties objecting to an application by the Co-op to upgrade their shop on the High Street to a full off-licensed premises from its then current beer only license. The Wolverton Co-Operative Society had taken on the tenancy of the general store on the High Street (now named “The old post office”) in late 1961. Understandably there was some concern at the potential competition offered by an off-license so close to The Nags Head. At a hearing before magistrates, the representative of the Licensed Victuallers’ Association offered that the two pubs in the village “were scraping a living” and there was a third not far away. it was further argued that the application was a stealthy way to create a distribution hub in the village for alcohol deliveries to other locations, an accusation firmly denied by the Co-op’s representative. However, a few weeks later, the Wolverton Express of December 29th, reported that the Co-op would be granted its license, on the proviso that wines and spirits could not be delivered outside of Great Linford, ignoring then the other concern about competition for the pubs in Great Linford.

But this is not quite the end of this tale, as several years later, the case re-emerged, with accusations that the Co-op had not held up its side of the bargain, and that beer was being covertly delivered to other villages from Great Linford. The Co-op argued that this had not been an official activity but conducted as a private matter between one of their managers and customers.

William was further named as one of the parties objecting to an application by the Co-op to upgrade their shop on the High Street to a full off-licensed premises from its then current beer only license. The Wolverton Co-Operative Society had taken on the tenancy of the general store on the High Street (now named “The old post office”) in late 1961. Understandably there was some concern at the potential competition offered by an off-license so close to The Nags Head. At a hearing before magistrates, the representative of the Licensed Victuallers’ Association offered that the two pubs in the village “were scraping a living” and there was a third not far away. it was further argued that the application was a stealthy way to create a distribution hub in the village for alcohol deliveries to other locations, an accusation firmly denied by the Co-op’s representative. However, a few weeks later, the Wolverton Express of December 29th, reported that the Co-op would be granted its license, on the proviso that wines and spirits could not be delivered outside of Great Linford, ignoring then the other concern about competition for the pubs in Great Linford.

But this is not quite the end of this tale, as several years later, the case re-emerged, with accusations that the Co-op had not held up its side of the bargain, and that beer was being covertly delivered to other villages from Great Linford. The Co-op argued that this had not been an official activity but conducted as a private matter between one of their managers and customers.

Norman Carter and The Nags Head on TV

The history of The Nags Head toward the latter half of the 1900s is presently largely unknown, except for a newspaper account from the Bucks Standard of July 23rd, 1965. This tells us that the landlord at the time was one Norman Carter, and that he was accused of having allowed one of his customers, William Spriggs of 11 Station Terrace, to consume intoxicating liquor after hours. Both men went to great lengths to argue their innocence but were fined £5 each.

Norman was also quoted in the Bucks Standard of February 11th, 1969, when the village was threatened with a curtailment in the beer supply. This was due to weight restrictions having been imposed on the Marsh Drive canal bridge. The story of the "Great Beer Shortage Panic of 1969" can be read here.

We do have one tantalising look at the pub from 1969, when it was briefly used as a location in a filmed episodic drama for Thames TV called Armchair Cinema. The episode in question was called “Suspect” and many scenes were shot in and around the village and canal. At one point, several characters are seen entering The Nags Head, followed by a scene purporting to be in the bar. Of course interiors were often shot in a studio, but we do know for certain that interiors were shot in the manor house, so it seems entirely likely the pub scenes were also shot in The Nags Head. In one other scene, Alex Carter, the son of the landlord, was drafted in to play a paperboy delivering to the manor house.

Norman was also quoted in the Bucks Standard of February 11th, 1969, when the village was threatened with a curtailment in the beer supply. This was due to weight restrictions having been imposed on the Marsh Drive canal bridge. The story of the "Great Beer Shortage Panic of 1969" can be read here.

We do have one tantalising look at the pub from 1969, when it was briefly used as a location in a filmed episodic drama for Thames TV called Armchair Cinema. The episode in question was called “Suspect” and many scenes were shot in and around the village and canal. At one point, several characters are seen entering The Nags Head, followed by a scene purporting to be in the bar. Of course interiors were often shot in a studio, but we do know for certain that interiors were shot in the manor house, so it seems entirely likely the pub scenes were also shot in The Nags Head. In one other scene, Alex Carter, the son of the landlord, was drafted in to play a paperboy delivering to the manor house.

Here for now we come to end of this history, but the Nags Head of course continues to be an important part of village life, still strongly associated with darts and running many events in aid of various charities. Click here to visit the website for The Nags Head.