The Black Horse Farm, Great Linford

The Black Horse farm presents a rather complex story, a narrative clouded by the fact that the histories of the farm and the inn of the same name (for many years with its own associated parcel of farmland) have long been intertwined with one another. Indeed, it seems entirely likely that the former was named for the latter, though exactly what, if any, historical, personal and business relationship existed between the two is a matter for conjecture. Click here to read more about the Black Horse Inn and its history as both pub and farm.

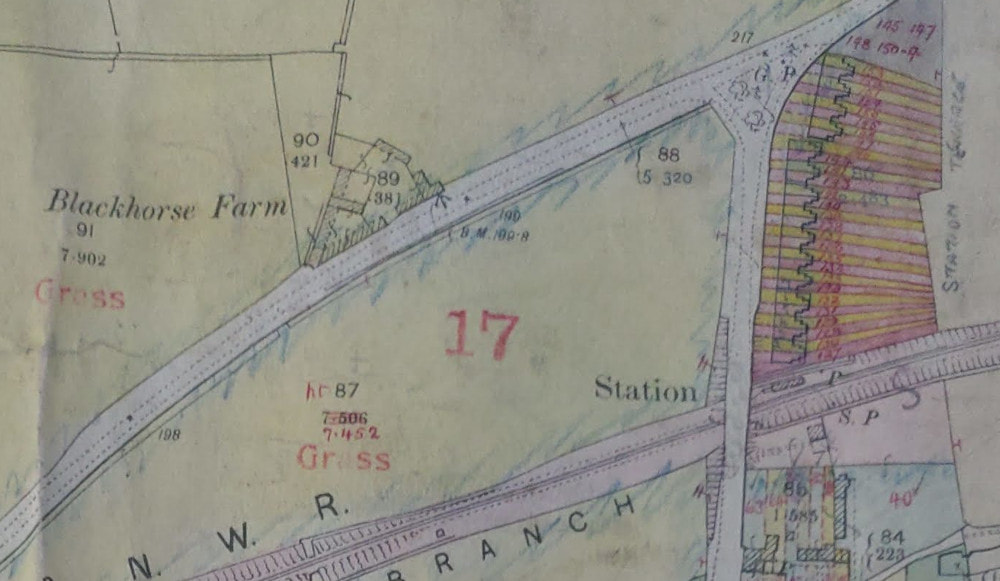

What does seem clear, is that at some time after 1840, a farmstead was established a mile to the east of the inn, on land directly adjoining the 161 acres included with the pub’s tenancy. The former location of the farmstead is shown on the map below.

The Black Horse farm presents a rather complex story, a narrative clouded by the fact that the histories of the farm and the inn of the same name (for many years with its own associated parcel of farmland) have long been intertwined with one another. Indeed, it seems entirely likely that the former was named for the latter, though exactly what, if any, historical, personal and business relationship existed between the two is a matter for conjecture. Click here to read more about the Black Horse Inn and its history as both pub and farm.

What does seem clear, is that at some time after 1840, a farmstead was established a mile to the east of the inn, on land directly adjoining the 161 acres included with the pub’s tenancy. The former location of the farmstead is shown on the map below.

The new farmstead, which came to be called the Black Horse Farm, has by now been completely erased from the landscape, but if the construction date is opaque, we can at least pinpoint when it was not there. A tithe map produced in 1840 (Buckinghamshire Archives Tithe/255) shows only one solitary building (likely a barn or other such ancillary structure) on the future site of the farmstead, in the bottom left corner of a field known as Shorts Ends, numbered 161 on the tithe map apportionments. This field was located on the Turnpike Road (now known as the Wolverton Road) approximately 250 meters from the turning to the road that would become modern day Marsh Drive, and along with seven other fields totalling 143 acres was then in the occupation (meaning he was renting the land) of a Benjamin Goodman. Unsurprisingly the land was in the ownership of the Uthwatts, the Lords of Great Linford Manor.

The 1841 census for the village contains only one person with the surname Goodman, a 20-year-old lacemaker named Mary, but no relationship to Benjamin is evident. In fact, Benjamin was living elsewhere, as he appears in the electoral poll books of 1837 and 1838, with his abode listed as “Woolverton Mill”, though he is none-the-less noted as a voter of Great Linford. This is because the value of the land Benjamin was farming at Great Linford bestowed upon him voting rights in the parish, as in fact did his occupation of a mill and land at Wolverton, thereby giving him two votes!

Benjamin Goodman does appear in the Post Office trade directory for the village produced in 1847, but though he is described as a farmer, the directory does not name his farm. He appears in neither the 1851 census for the village, nor the Musson & Craven’s trade directory of 1853, so we can presume he had relinquished his tenancy by this time, or had passed away, though a record of death presently eludes discovery.

By 1881, when the first detailed 25 inch to the mile map of the parish was produced by the Ordnance Survey, the single building located on the land farmed in 1840 by Benjamin Goodman can be seen to have swelled to a significant cluster of structures. However, it is unlabelled and sadly no picture has come to light which would show us what this looked like. To view the 1881 OS map of Great Linford, click here.

We do however have a very good description from a sales brochure prepared in 1951 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-AR/4/33), which is worth reproducing in full. It should of course be noted that this is a description of the farm in 1951, and many changes may have been made to the farmstead since it was first constructed.

Benjamin Goodman does appear in the Post Office trade directory for the village produced in 1847, but though he is described as a farmer, the directory does not name his farm. He appears in neither the 1851 census for the village, nor the Musson & Craven’s trade directory of 1853, so we can presume he had relinquished his tenancy by this time, or had passed away, though a record of death presently eludes discovery.

By 1881, when the first detailed 25 inch to the mile map of the parish was produced by the Ordnance Survey, the single building located on the land farmed in 1840 by Benjamin Goodman can be seen to have swelled to a significant cluster of structures. However, it is unlabelled and sadly no picture has come to light which would show us what this looked like. To view the 1881 OS map of Great Linford, click here.

We do however have a very good description from a sales brochure prepared in 1951 (Buckinghamshire Archives D-AR/4/33), which is worth reproducing in full. It should of course be noted that this is a description of the farm in 1951, and many changes may have been made to the farmstead since it was first constructed.

Particulars

of the

VALUABLE FREEHOLD ATTESTED

DAIRY FARM

known as

Black Horse Farm, Great Linford

NEWPORT PAGNELL

situated on the Main Newport Pagnell and Wolverton Road in the very productive valley of the Ouse, comprising of a Stone and Brick built FARM HOUSE

having the following accommodation: -

Ground Floor:

LOUNGE HALL, approximately 15ft. x 12ft. with grate and tiled floor.

DRAWING ROOM, approximately 15ft. x 12ft. with modern tiled grate and oak surround.

DINING ROOM, approximately 10ft. x 10ft (excluding Bay) with tiled hearth and oak surround and bay window.

KITCHEN, approximately 16ft x 12ft with tiled floor, fitted dresser with cupboards and drawers, kitchen range with Welsh baking oven and Beeston hot water heater. Adjoining is a Pantry with ample shelves.

SCULLERY with sink (h and c.) copper, gas point for cooker. Coal Barn.

First Floor:

3 Double Bedrooms and 2 Single Bedrooms and Bathroom fitted with Bath (h. and c.), Lavatory Basin (h. and c.) and W.C.

Second Floor:

Four good Attics.

THE GARDEN

Comprises a small pleasure garden and a productive kitchen garden containing fruit trees including, Pears, Greengage, Apple and Plum.

THE FARM BUILDINGS

which are in good order are mainly built of stone and brick with tiled or slated roofs are conveniently situated on the Main Newport Pagnell, Wolverton road at a convenient distance from the Farm house and comprise:- Cowhouse for 20, Cowhouse for 9, both fitted with gravity feed drinking bowls. Large fitted Dairy with sink and slate draining board and Electric power point. Boiler room and Coal store, with Martins Boiler. Food store and Mixing room, Store place, Range of 3 Isolation boxes all surrounding a small yard. Adjoining and surrounding a concrete yard is an Isolation box fitted with mangers and hayrack; 4 bay open cattle hovel and yard with concrete and stone floor; Bull pen and run; Stabling for 8; 3 calf boxes, 2 bay Implement hovel and large Barn with loft over part. In the Rick Yard is a Chaff House, Cow House for 8 calf boxes; 3 bay Implement Shed and Tractor House together with a 2 bay Cart Hovel. In No. 96 and 87 are timber and corrugated 3 bay open hovels and yards, in O.S. No. 95 is a sheep pen.

Company's Electric Light and Gas. Main Water.

THE LAND

Which is in excellent heart and condition has been very well farmed and comprises some rich grazing land running down to the river Ouse. Silage clamps have been constructed in O.S. No 91 and 98.

THE COTTAGE

adjoins the main road and is occupied by a Service Tenant. It is built of stone with slated roof and contains 2 living rooms and 3 bedrooms. Outside is a Barn and a Closest, and a small garden.

The shooting is let and produces £6/6/- per annum. The Newport Pagnell R.D.C. pay a rent of £2/0/0 per annum in respect of the poles carrying the electric current to the pumping station in O.S. No 91.

As the above description makes clear, by 1951 there was certainly a substantial farmhouse with additional accommodation for farm workers, but it has proven surprisingly difficult to place anyone physically resident at the Black Horse Farm, suggesting that the farmhouse and cottage were only sporadically occupied.

Adding to an already complex situation, it appears as if the Black Horse Farm was considered for a time a part of the parish of Stantonbury, at least for the purposes of the 1881 census. Stantonbury (including the remains of the old medieval village of Stanton Low) was at this time tiny, barely able to muster sufficient inhabitants to fill a single census page, but on the page given over to a “Description of the enumeration district”, we find the following intriguing line, “The whole of the parish of Great Linford including the Black Horse Farm.” Also alluded to are some cottages near the farm. It is odd then that that a census for Stantonbury is described as if it is part and parcel of Great Linford.

Equally oddly, even though the enumerator (who happened to be Henry Bird of Windmill Hill Farm) had noted the existence of a Black Horse Farm in his preamble, the farm is not actually named on the census sheet, with the only reference to a farm being one of 375 acres in the occupation of a Thomas Selby. This unnamed farm does not however seem likely to be the Black Horse Farm, but rather a farmstead further to the west on the Newport Road, known as The Stantonbury Farm.

Adding to the mystery, also on the same census page is a 66-year-old shepherd named Timothy Barnett, born in 1815. His address is given as Stanton Low, but in 1883 a person of the same name appears in that year’s Kelly Trade directory as a farmer at Great Linford, as he does again in the 1887 edition. The farm is not named in either directory, but we might speculate that Timothy Barnett was one of the earliest inhabitants of the Black Horse Farm.

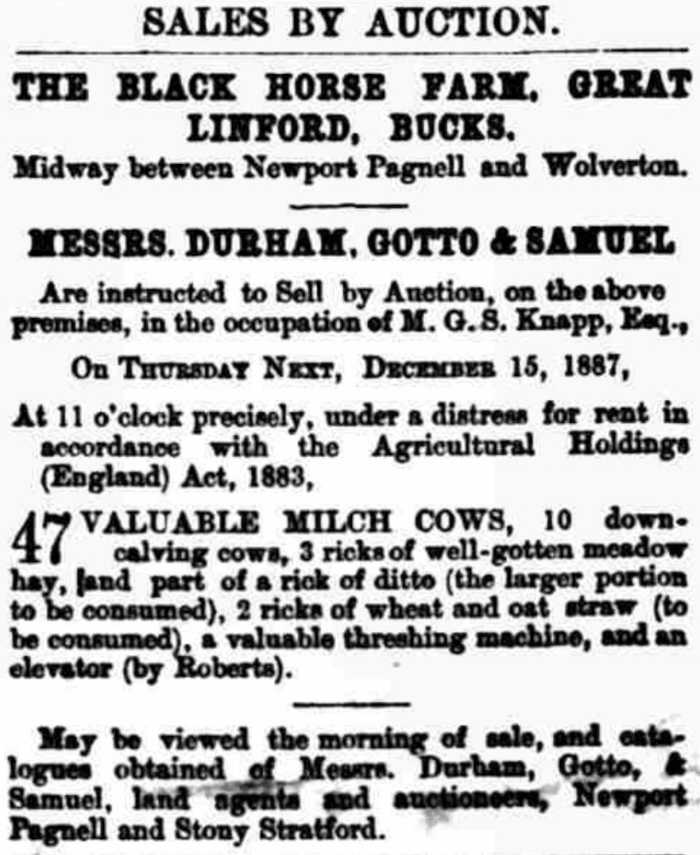

Croydon’s Weekly Standard of December 10th, 1887, tell us that an auction was to be held at “Black Horse Farm” and that it was occupied by an M. G. S. Knapp esquire. However, the use of the term “occupation” may not be all it seems, in this case very likely meaning only that the person in question was renting the farm, but not necessarily living there. This seems highly probable as we can identify M. G. S. Knapp as Matthew Grenville Samwell Knapp of Little Linford Hall. It does seem unlikely he would swap the familiar home comforts of his manor house for a farmhouse, nor would he have wanted to get his hands dirty as farmer, though lacking another name to place at the farm, we cannot entirely discount the possibility.

Perhaps it was Timothy Barnett who was in the employ of Matthew Knapp at the Black Horse Farm. Timothy died in 1890, and in 1891, his niece Anne Martin is listed in the 1891 Kelly’s directory as a farmer in Great Linford, the inference being that she had succeeded him in the tenancy of the same farm. Intriguingly, we previously find Anne on the 1871 census at Stanton Low, where she is recorded as a farmer of 206 acres, employing 2 labourers. Anne was then living in the household of her grandmother.

Anne does not appear on the 1891 census at Great Linford (she had married that year and moved to Northamptonshire), but it does not seem unreasonable to presume that we have some (admittedly circumstantial) evidence to place both her and her uncle Timothy at the Black Horse Farm.

Returning to the sale of 1887, the advertisement lists for sale “47 valuable milch cows”, milch being an old word for milk, 10 “down calving cows”, which is to say cows that are about to give birth, plus a variety of other lots including a threshing machine and a grain elevator. An intriguing aspect of the advertisement is the information that the sale is being held “under a distress for rent in accordance with the Agricultural Holdings (England) Act, of 1883.” On the face of it, it seems odd to imagine that the lord of Little Linford was unable to pay his bills, but lacking any corroborating documents to confirm what was happening, the circumstances of his departure must for now remain a mystery.

Adding to an already complex situation, it appears as if the Black Horse Farm was considered for a time a part of the parish of Stantonbury, at least for the purposes of the 1881 census. Stantonbury (including the remains of the old medieval village of Stanton Low) was at this time tiny, barely able to muster sufficient inhabitants to fill a single census page, but on the page given over to a “Description of the enumeration district”, we find the following intriguing line, “The whole of the parish of Great Linford including the Black Horse Farm.” Also alluded to are some cottages near the farm. It is odd then that that a census for Stantonbury is described as if it is part and parcel of Great Linford.

Equally oddly, even though the enumerator (who happened to be Henry Bird of Windmill Hill Farm) had noted the existence of a Black Horse Farm in his preamble, the farm is not actually named on the census sheet, with the only reference to a farm being one of 375 acres in the occupation of a Thomas Selby. This unnamed farm does not however seem likely to be the Black Horse Farm, but rather a farmstead further to the west on the Newport Road, known as The Stantonbury Farm.

Adding to the mystery, also on the same census page is a 66-year-old shepherd named Timothy Barnett, born in 1815. His address is given as Stanton Low, but in 1883 a person of the same name appears in that year’s Kelly Trade directory as a farmer at Great Linford, as he does again in the 1887 edition. The farm is not named in either directory, but we might speculate that Timothy Barnett was one of the earliest inhabitants of the Black Horse Farm.

Croydon’s Weekly Standard of December 10th, 1887, tell us that an auction was to be held at “Black Horse Farm” and that it was occupied by an M. G. S. Knapp esquire. However, the use of the term “occupation” may not be all it seems, in this case very likely meaning only that the person in question was renting the farm, but not necessarily living there. This seems highly probable as we can identify M. G. S. Knapp as Matthew Grenville Samwell Knapp of Little Linford Hall. It does seem unlikely he would swap the familiar home comforts of his manor house for a farmhouse, nor would he have wanted to get his hands dirty as farmer, though lacking another name to place at the farm, we cannot entirely discount the possibility.

Perhaps it was Timothy Barnett who was in the employ of Matthew Knapp at the Black Horse Farm. Timothy died in 1890, and in 1891, his niece Anne Martin is listed in the 1891 Kelly’s directory as a farmer in Great Linford, the inference being that she had succeeded him in the tenancy of the same farm. Intriguingly, we previously find Anne on the 1871 census at Stanton Low, where she is recorded as a farmer of 206 acres, employing 2 labourers. Anne was then living in the household of her grandmother.

Anne does not appear on the 1891 census at Great Linford (she had married that year and moved to Northamptonshire), but it does not seem unreasonable to presume that we have some (admittedly circumstantial) evidence to place both her and her uncle Timothy at the Black Horse Farm.

Returning to the sale of 1887, the advertisement lists for sale “47 valuable milch cows”, milch being an old word for milk, 10 “down calving cows”, which is to say cows that are about to give birth, plus a variety of other lots including a threshing machine and a grain elevator. An intriguing aspect of the advertisement is the information that the sale is being held “under a distress for rent in accordance with the Agricultural Holdings (England) Act, of 1883.” On the face of it, it seems odd to imagine that the lord of Little Linford was unable to pay his bills, but lacking any corroborating documents to confirm what was happening, the circumstances of his departure must for now remain a mystery.

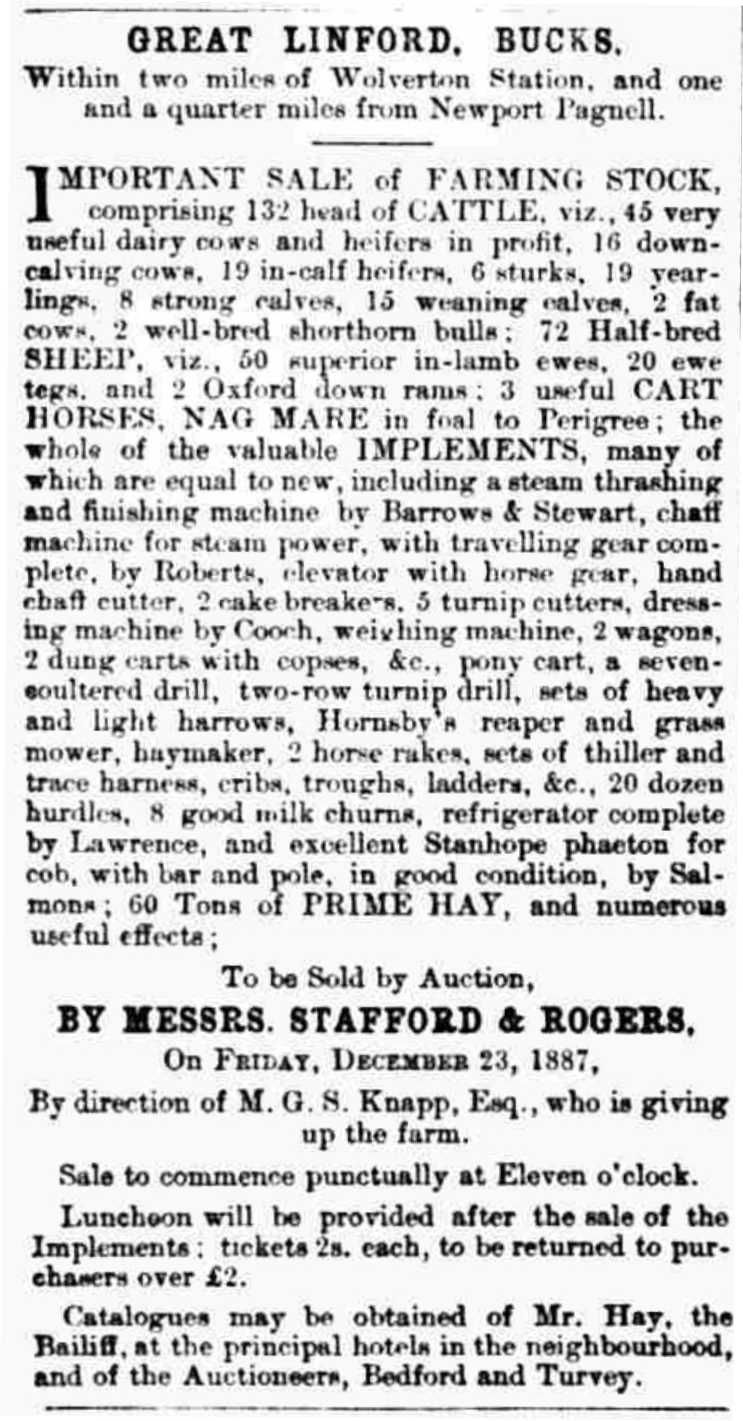

A substantially more detailed advert appears on the same page of the newspaper that also includes a copious list of agricultural implements and machinery, certainly giving every appearance of a well equipped farm.

We are left with one other mystery concerning this period in the history of the Black Horse Farm, who was the owner, though in the absence of any other evidence, the presumption must be that it was the Uthwatts of Great Linford Manor, who of course we know did own the land in 1840.

William Hedges

A story appearing in Croydon's Weekly Standard of July 30th, 1892, sheds new light on the occupation of the Back Horse Farm. The tale is a curious one, concerning a near riot that occurred on the village green. A large crowd had gathered there to hear a political speech and having been stirred up by the passions of the election campaign then underway, had reportedly attacked a farmer named William Hedges. The newspaper reports on the resulting court case reveal that William had testified he was travelling between The Black Horse Farm and Lodge Farm at the time of the assault, the latter then being his residence. For further information on the circumstances of this melee on the green, click here.

We can be reasonably confident that William Hedges was the new tenant of the Black Horse Farm; he was in fact a very successful farmer at this time, farming not only the Black Horse Farm, but also Lodge Farm. Reflecting his prosperity, the 1901 census places William and his family at neither farm, but rather at Great Linford House, a large building that once stood on the land now occupied by Church Farm Crescent.

The Black Horse Farm is not specifically named in the Kelly’s trade directory of 1903 or 1907, but William's continuing connection is categorically confirmed by a valuation office survey map produced in 1910 for the parish (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5.) The map is extremely illuminating, showing that the land formally associated with the Black Horse Inn has been largely merged with that of the Black Horse Farm into a combined enterprise of 214 acres; a figure that is worth remarking upon, as it is close to the 206 acres that Annie Martin was farming in 1871. The Inn (now occupied by a Frederick P Malacley) had retained a meagre rump of land measuring 13 acres, and there is firm evidence that a small herd of dairy cattle were maintained here in subsequent years.

We can be reasonably confident that William Hedges was the new tenant of the Black Horse Farm; he was in fact a very successful farmer at this time, farming not only the Black Horse Farm, but also Lodge Farm. Reflecting his prosperity, the 1901 census places William and his family at neither farm, but rather at Great Linford House, a large building that once stood on the land now occupied by Church Farm Crescent.

The Black Horse Farm is not specifically named in the Kelly’s trade directory of 1903 or 1907, but William's continuing connection is categorically confirmed by a valuation office survey map produced in 1910 for the parish (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/5.) The map is extremely illuminating, showing that the land formally associated with the Black Horse Inn has been largely merged with that of the Black Horse Farm into a combined enterprise of 214 acres; a figure that is worth remarking upon, as it is close to the 206 acres that Annie Martin was farming in 1871. The Inn (now occupied by a Frederick P Malacley) had retained a meagre rump of land measuring 13 acres, and there is firm evidence that a small herd of dairy cattle were maintained here in subsequent years.

The valuation office survey map provides several other useful details, that the ownership of all the land in question was still in the hands of the Uthwatts, and that the Black Horse Farm consisted of buildings, land and a cottage; the land is numbered 17 on the map. The cottage is occupied by a John Wallis, and though he cannot be found on the 1911 census, a 43-year-old man of the same name is listed on the 1901 census, where he is described as an agricultural labourer and milkman.

The 1911 census has one possible reference to the farm; the census enumerator’s path around the village can be tentatively retraced from the document, thus we can see him passing through the Wharf and down Railway Terrace. Here he arrived at a “Great Linford Farm”, where we find Charles Frederick Newbury, an agricultural labourer, and his family. This rather vague name for farm is not at all helpful, but it does seem likely that this is in fact the Black Horse Farm.

The 1911 census has one possible reference to the farm; the census enumerator’s path around the village can be tentatively retraced from the document, thus we can see him passing through the Wharf and down Railway Terrace. Here he arrived at a “Great Linford Farm”, where we find Charles Frederick Newbury, an agricultural labourer, and his family. This rather vague name for farm is not at all helpful, but it does seem likely that this is in fact the Black Horse Farm.

An empty farm?

In 1918 a landmark change was made to the voting system in the country, with women attaining the right to vote, but also a considerable extension of voting rights in general for both sexes. As a result of this, electoral rolls become available, naming not only the persons registered to vote, but their abode. We can therefore scour the rolls for anyone listed as registered to vote at the Black Horse Farm, finding in fact very few; there is for instance no mention of the farm on the 1918 rolls, nor in fact until 1931 do we find anyone at all registered at the address, a Margaret Olive Sinfield, though this is the only reference found anywhere to a person of this name.

Throughout all this time, the Uthwatts had continued to own the farm. The Bedfordshire Times and Independent of September 15th, 1922, noted that the executors of William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921) had instructed an auctioneer to sell off the live and dead stock of the Black Horse Farm, the farm itself having been let, though to whom it does not elaborate.

Throughout all this time, the Uthwatts had continued to own the farm. The Bedfordshire Times and Independent of September 15th, 1922, noted that the executors of William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921) had instructed an auctioneer to sell off the live and dead stock of the Black Horse Farm, the farm itself having been let, though to whom it does not elaborate.

Horace Corcoran Patterson

The 1924 Kelly’s trade directory entry for the village names Horace Corcoran Patterson in connection with the Black Horse Farm. Horace was born at Baldock in Hertfordshire on October 11th, 1894, to Alfred and Gertrude Patterson. The family can be found at Baldock on the 1911 census, where Alfred’s profession is described as saddler, motor and cycle dealer, a fascinating example of someone transitioning along with society at large from one form of transport to another. Horace himself however is described as a "farmer pupil." He served in the first world war, and we know he had returned to Baldock by the time of the 1921 census, but quite conceivably it was Horace who was let the Black Horse farm in 1922. He is not listed on the electoral roll for the village until 1923, though intriguingly his address is not the Black Horse farmstead, but at nearby Wharf House.

In April that same year banns were posted at Aylsham in Norfolk for his forthcoming marriage to Muriel Mary Wade; the banns clearly state that he was then resident at Great Linford. They appear to have only had one child, a son, Thomas Rupert Patterson born in 1928, one might reasonably presume at the Black Horse Farm, if not for the dissenting fact that the 1928 electoral roll places Horace and his wife again at Wharf House. In fact, the rolls from 1923 through to 1931, the last presently investigated, show their address consistently as Wharf House.

However, that Horace was farming at the Black Horse Farm seems indisputable, as we find several references to Thomas and Muriel at the farm in newspaper stories throughout the early 1930s. On Saturday April 12th, 1930, seven of Horace’s cattle made a break for greener pastures and were reported by a passing motorist to be straying on the Newport Road. A Police Constable Bunce duly attended and having confirmed the escape, roused one of the farmhands from his bed to apprehend them. For not having made better efforts to secure his cattle, Horace was fined 12 shillings.

Reflecting the grim poverty often besetting people during the so-called Great Depression, in May of 1931, two men were charged with stealing from Horace four railway sleepers for firewood. The Northampton Chronicle and Echo of the 28th reported that one of the men had been out of work for several months, but the bench showed no leniency and fined both 30 shillings each.

Horace was back before the magistrates again in September of 1932, with an account published in the Wolverton Express that he had purchased 12 pigs from Banbury market but had failed to isolate them as required to avoid the spread of swine fever, instead mixing them in with other pigs on the farm. This oversight lost him another 12 shillings, plus four for costs. Then in 1935, it was the turn of his wife Muriel to have a run-in with the law, fined five shillings for failing to produce an insurance certificate for a lorry she had been driving through Snetterton.

This is the last reference found to the family that places them at the Black Horse Farm, and by the time of the 1939 register conducted on the eve of WW2, Horace and his wife and son have moved to a farm known as The Walnuts at Newport Pagnell. However, it seems they retained a firm connection to the village and continued to farm there, though where is presently uncertain. The evidence for this is to be found in a 1948 issue of the Bucks Standard, which reports upon the silver wedding anniversary of Horace and his wife. The article states that though residing at The Walnuts, Horace had farmed at Great Linford for the entire 25 years of their marriage, with the article specifically describing him as a poultry farmer. Muriel is also described as a bastion of village and church life, noting that she was a church warden and had been involved in the provision of electric light to St. Andrews.

In April that same year banns were posted at Aylsham in Norfolk for his forthcoming marriage to Muriel Mary Wade; the banns clearly state that he was then resident at Great Linford. They appear to have only had one child, a son, Thomas Rupert Patterson born in 1928, one might reasonably presume at the Black Horse Farm, if not for the dissenting fact that the 1928 electoral roll places Horace and his wife again at Wharf House. In fact, the rolls from 1923 through to 1931, the last presently investigated, show their address consistently as Wharf House.

However, that Horace was farming at the Black Horse Farm seems indisputable, as we find several references to Thomas and Muriel at the farm in newspaper stories throughout the early 1930s. On Saturday April 12th, 1930, seven of Horace’s cattle made a break for greener pastures and were reported by a passing motorist to be straying on the Newport Road. A Police Constable Bunce duly attended and having confirmed the escape, roused one of the farmhands from his bed to apprehend them. For not having made better efforts to secure his cattle, Horace was fined 12 shillings.

Reflecting the grim poverty often besetting people during the so-called Great Depression, in May of 1931, two men were charged with stealing from Horace four railway sleepers for firewood. The Northampton Chronicle and Echo of the 28th reported that one of the men had been out of work for several months, but the bench showed no leniency and fined both 30 shillings each.

Horace was back before the magistrates again in September of 1932, with an account published in the Wolverton Express that he had purchased 12 pigs from Banbury market but had failed to isolate them as required to avoid the spread of swine fever, instead mixing them in with other pigs on the farm. This oversight lost him another 12 shillings, plus four for costs. Then in 1935, it was the turn of his wife Muriel to have a run-in with the law, fined five shillings for failing to produce an insurance certificate for a lorry she had been driving through Snetterton.

This is the last reference found to the family that places them at the Black Horse Farm, and by the time of the 1939 register conducted on the eve of WW2, Horace and his wife and son have moved to a farm known as The Walnuts at Newport Pagnell. However, it seems they retained a firm connection to the village and continued to farm there, though where is presently uncertain. The evidence for this is to be found in a 1948 issue of the Bucks Standard, which reports upon the silver wedding anniversary of Horace and his wife. The article states that though residing at The Walnuts, Horace had farmed at Great Linford for the entire 25 years of their marriage, with the article specifically describing him as a poultry farmer. Muriel is also described as a bastion of village and church life, noting that she was a church warden and had been involved in the provision of electric light to St. Andrews.

William Morgan

The 1939 register provides that a William Morgan, born June 18th, 1895, was a dairy farmer at The Black Horse Farm, alongside 23-year-old Glenville Morgan (possibly first name John and presumably William’s son) and 29-year-old Mary M Brown, a stock keeper.

The Wolverton Express of May 30th, 1947, reports that an attempt had been made to sell 57 acres of the farm, but bidding having reached £2,600, it was withdrawn for failing to reach its reserve. The farm is clearly visible on an aerial photograph taken in 1948, though it is all too obvious that the gravel pits established in the vicinity are heavily encroaching upon its lands. To view the aerial photograph of the Black Horse Farm, click here.

In August 1951, the farm was put up for sale by auction on the instructions of W Morgan Esq. It is clear from the aforementioned sale catalogue that he was the owner, so the Uthwatts had by now disinvested themselves of the property. The sale brochure, prepared by the firm of P. C. Gambell (the text of which is reproduced earlier in this history) indicates that the farm was to be sold unoccupied, though there was now just 71 acres of land, half what it had been a few decades ago, so the abortive sale of 1947 appears to have succeeded on a subsequent try. The sale was to take place at the Swan Hotel, Newport Pagnell, on August 10th. The successful bidder was reported to be an R. E Watts of Nash, who paid £7.000.

The Wolverton Express of May 30th, 1947, reports that an attempt had been made to sell 57 acres of the farm, but bidding having reached £2,600, it was withdrawn for failing to reach its reserve. The farm is clearly visible on an aerial photograph taken in 1948, though it is all too obvious that the gravel pits established in the vicinity are heavily encroaching upon its lands. To view the aerial photograph of the Black Horse Farm, click here.

In August 1951, the farm was put up for sale by auction on the instructions of W Morgan Esq. It is clear from the aforementioned sale catalogue that he was the owner, so the Uthwatts had by now disinvested themselves of the property. The sale brochure, prepared by the firm of P. C. Gambell (the text of which is reproduced earlier in this history) indicates that the farm was to be sold unoccupied, though there was now just 71 acres of land, half what it had been a few decades ago, so the abortive sale of 1947 appears to have succeeded on a subsequent try. The sale was to take place at the Swan Hotel, Newport Pagnell, on August 10th. The successful bidder was reported to be an R. E Watts of Nash, who paid £7.000.

The last days of the Black Horse Farm

No clear picture of who R. E. Watts was has come to light and hereafter the trail goes cold; the Ordnance Survey map of 1972 shows the farmstead still in place, but newspapers appear devoid of any mention of the farm or its owners and occupiers. When the farmstead was finally demolished is something that is yet to be determined, but it is clear that the gravel pits that had been established in the parish had for some time been encroaching even further on the farm’s land, which undoubtedly contributed to its eventual demise.