Wood Farm, Great Linford

Wood Farm is one of several Great Linford farms sadly lost to modern development, for which no description has come to light, nor its estimated age and origins. However, we can pinpoint the farmstead’s location to the junction between Teasel Avenue and Marjoram Place in the modern-day estate of Conniburrow, then part of the historic parish of Great Linford. The farm clearly derived its name from its close proximity to the south end of Linford Wood. But there was also a Wood End Farm to the north end of Linford Wood, and as neither farmstead was consistently named from year to year, a degree of uncertainty is unavoidable in attempting to chart their histories.

Above, the former location of Wood Farm.

One undated aerial photograph of the farm has come to light of the farmstead, which is reproduced below.

Valentine Dunkley

That there was a Wood Farm in the parish by at least 1837 seems certain, as the elector's poll book published that year names a Valentine Dunkley as the resident voter. Yet, despite boasting a rather distinctive name, Valentine’s origins have remained somewhat obscure. He and his family undoubtedly had strong connections to East Hadden in Northamptonshire, and the 1851 census gives us a birth year of circa 1789, but a baptism record eludes discovery, and census records provide either illegible or contradictory information as to his place of birth. At best, the 1861 census (by which time he had returned to East Haddon) tells us that his place of birth was Brington, also in Northamptonshire; that East Haddon and Brington are only a few miles apart is surely significant?

As to Valentine’s family, he had married a Susannah Moore at East Haddon on December 20th, 1807, with evidence to date suggesting they had only one child, a son John, born there in 1810. John Jnr married an Eliza Cory at Brington in 1829, and they had five children, one of whom, yet another John, was born at Great Linford in 1838; all their other children were born at East Hadden.

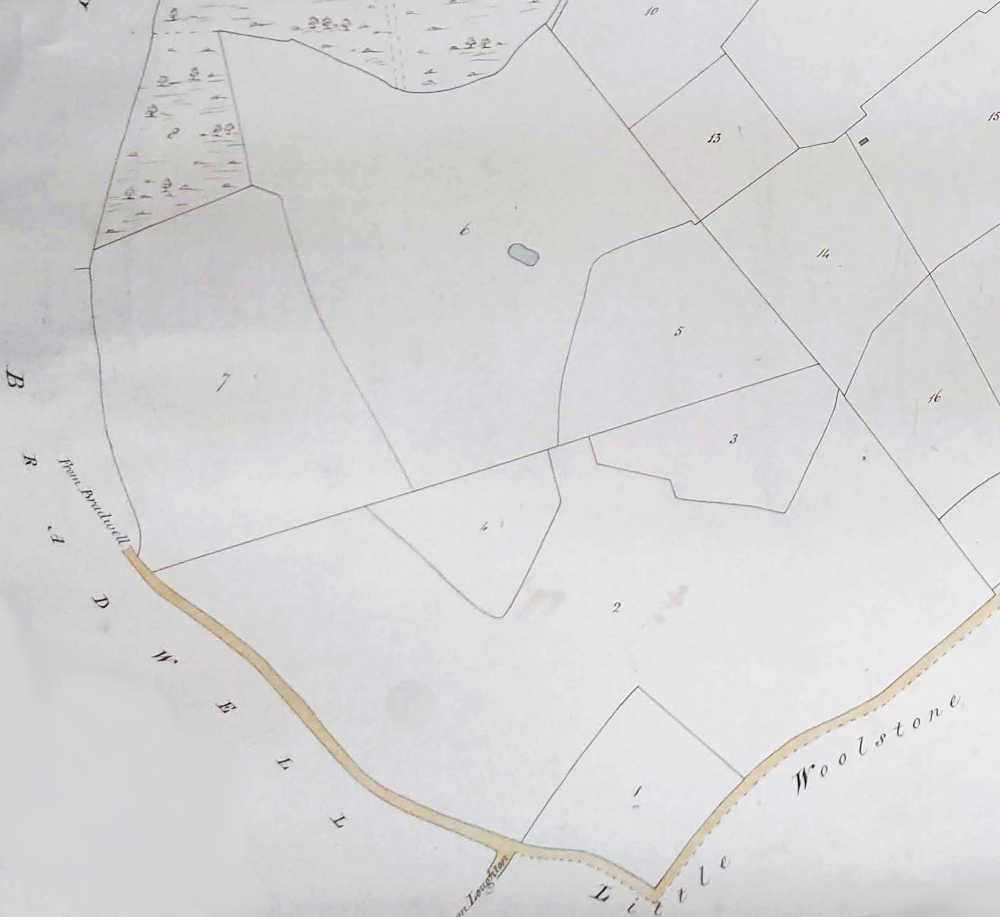

Valentine was widowed in 1835 and perhaps it was the death of Susannah (at East Hadden) that motivated him to seek out a new start at Great Linford. He is to be found on the 1840 tithe map for Great Linford (Buckinghamshire Archives, Tithe/255), but only in connection to 166 acres of arable and graze land located immediately to the south of Linford Wood, not a property. As was the case with almost all the farmland in the parish, this was owned by the then Lord of the Manor, Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, but the lack of a farmhouse on the land presents a problem, as we do not know where Valentine was living in the parish at this time. Clearly, he must have had a roof over his head, as is recorded in the parish on the census of 1841, though as is normal for this document, no detail is given as to his location.

As to Valentine’s family, he had married a Susannah Moore at East Haddon on December 20th, 1807, with evidence to date suggesting they had only one child, a son John, born there in 1810. John Jnr married an Eliza Cory at Brington in 1829, and they had five children, one of whom, yet another John, was born at Great Linford in 1838; all their other children were born at East Hadden.

Valentine was widowed in 1835 and perhaps it was the death of Susannah (at East Hadden) that motivated him to seek out a new start at Great Linford. He is to be found on the 1840 tithe map for Great Linford (Buckinghamshire Archives, Tithe/255), but only in connection to 166 acres of arable and graze land located immediately to the south of Linford Wood, not a property. As was the case with almost all the farmland in the parish, this was owned by the then Lord of the Manor, Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, but the lack of a farmhouse on the land presents a problem, as we do not know where Valentine was living in the parish at this time. Clearly, he must have had a roof over his head, as is recorded in the parish on the census of 1841, though as is normal for this document, no detail is given as to his location.

The eight fields in the occupancy of Valentine are numbered on the map as: #1 (Seckley Hill South), #2 (Seckley Hill North), #3 (Seckley Hill East), #4 (Seckley Hill Middle), #5 (East Poor Ground), #6 (House Ground), #7 (West Poor Ground) and #13 (Brier Hedge Close.) The fields are a mix of arable and grazing, while the name Seckley may be variation on Secklow after the folk-moot Secklow Mound that served as a meeting place for the inhabitants of this medieval "hundred." This was the system of administration into which the country was for a many centuries divided. The inclusion of a "House Ground" is also of interest; as while no house is illustrated, we might imagine that the name was intended to be propitious of a house yet to be. The only problem with this theory is that the eventual location of Wood Farm would be closer to the field labelled as #10 (South West Neathill), that at this time was in the occupation of James Harley, of the farmhouse that would come to be known as The Cottage.

The 1841 census shows that the widowed Valentine was alone, other than for several servants, but he is described as a farmer, as is also the case in the next census of 1851. This census provides more detail, confirming that he is resident at Wood Farm and is farming 166 acres, which is an exact match to the figure provided on the tithe map a decade earlier. He has not remarried, and the only other person present in his household is an 18-year-old servant, a local girl named Sarah Fennimore. Clearly by this time we must presume that a farmstead has been constructed upon his farmland, though he was likely to be renting it from the Uthwatts.

In 1860, Valentine’s tenancy at Wood Farm came to an end, an advert placed in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of September 15th, announcing a sale to be held on the 29th. The livestock up for auction included a flock of 108 sheep, “5 fat hogs”, 10 cows, plus heifers and sturks; the latter a term for a heifer or bullock about two years old. In addition, Valentine was also disposing of “7 useful cart horses” and a selection of his household furniture, plus a great deal of farm equipment. Notable among the items for sale is a collection of brewing utensils; it is common to find such equipment in the possession of farmers, so clearly a great deal of home brewing was going on within the parish.

We have several unfortunate epilogues to the story of Valentine Dunkley. In 1864, he found himself in the sad position of having to sue his own son. This arose over the disposition of some furniture that Valentine had removed from Great Linford to his son’s house and an unpaid loan of £15. On departing Great Linford in 1860 he had moved in with his son, but as explained in the account of the case (Northampton Mercury, November 12th, 1864) the relationship had soured. This prompted Valentine to move out to live with his grandson John, who had by now married and set up in business as a shoemaker in the Northamptonshire village of Ravensthorpe.

Valentine had attempted to recover the furniture but was prevented from doing so by his son. The arguments presented in court as to the true ownership of the furniture lay bare a bitter dispute, but Valentine was vindicated and justice served in his favour, to which his son reacted with barely concealed malice, departing the court in a fury and saying of his father that he was, “an old rogue.”

As a final fascinating but tragic sidebar to the story of the Dunkley’s, Valentine had another grandson by John, a namesake who perished in 1878, one of an estimated 600-700 persons drowned in an infamous accident on the river Thames, when a passenger paddle steamer called the SS Princess Alice collided with the collier SS Bywell Castle.

The 1841 census shows that the widowed Valentine was alone, other than for several servants, but he is described as a farmer, as is also the case in the next census of 1851. This census provides more detail, confirming that he is resident at Wood Farm and is farming 166 acres, which is an exact match to the figure provided on the tithe map a decade earlier. He has not remarried, and the only other person present in his household is an 18-year-old servant, a local girl named Sarah Fennimore. Clearly by this time we must presume that a farmstead has been constructed upon his farmland, though he was likely to be renting it from the Uthwatts.

In 1860, Valentine’s tenancy at Wood Farm came to an end, an advert placed in Croydon’s Weekly Standard of September 15th, announcing a sale to be held on the 29th. The livestock up for auction included a flock of 108 sheep, “5 fat hogs”, 10 cows, plus heifers and sturks; the latter a term for a heifer or bullock about two years old. In addition, Valentine was also disposing of “7 useful cart horses” and a selection of his household furniture, plus a great deal of farm equipment. Notable among the items for sale is a collection of brewing utensils; it is common to find such equipment in the possession of farmers, so clearly a great deal of home brewing was going on within the parish.

We have several unfortunate epilogues to the story of Valentine Dunkley. In 1864, he found himself in the sad position of having to sue his own son. This arose over the disposition of some furniture that Valentine had removed from Great Linford to his son’s house and an unpaid loan of £15. On departing Great Linford in 1860 he had moved in with his son, but as explained in the account of the case (Northampton Mercury, November 12th, 1864) the relationship had soured. This prompted Valentine to move out to live with his grandson John, who had by now married and set up in business as a shoemaker in the Northamptonshire village of Ravensthorpe.

Valentine had attempted to recover the furniture but was prevented from doing so by his son. The arguments presented in court as to the true ownership of the furniture lay bare a bitter dispute, but Valentine was vindicated and justice served in his favour, to which his son reacted with barely concealed malice, departing the court in a fury and saying of his father that he was, “an old rogue.”

As a final fascinating but tragic sidebar to the story of the Dunkley’s, Valentine had another grandson by John, a namesake who perished in 1878, one of an estimated 600-700 persons drowned in an infamous accident on the river Thames, when a passenger paddle steamer called the SS Princess Alice collided with the collier SS Bywell Castle.

John Orrell

It is interesting that the 1861 census makes no mention of a farmer at “Wood Farm.” Rather, the man present, along with his wife and children is an agricultural labourer named William Mapley. Before we jump to conclusions, it is important to note that census enumerators were concerned only with recording where persons were on the night of the census, not necessarily where they normally lived, so perhaps the farmer was elsewhere that night, but equally there might have been no appointed tenant at the time, and William Mapley was in essence caretaking at the farmstead.

The name John Orrell now enters the frame, and though he appears in no trade directory or census record for the parish, there is evidence to place him at Wood Farm in the early 1860s. John was born at Liverpool circa 1838, and aged 24 is listed on the 1861 census as a pupil lodging at a farm at Tickford, Newport Pagnell, presumably there to learn the trade. It was here that he must have met and courted Jessie Doig, the farmer’s daughter. Conceivably, the liaison was not warmly welcomed, as they married in London by license on November 5th, 1861, thereby evading the need to post banns at their local church.

Perhaps if they had indeed eloped this made a return to Tickford problematic, and a new home had to be found. The earliest report of John’s presence in Great Linford is from April 1862, when he became one of the parish overseers, a not uncommon appointment for a farmer. The couple's first child Francis Edith was baptised later in the year at Great Linford, on September 14th, 1862, but though the birth was also registered in the Newport Pagnell district (which covered Great Linford), later census records for Francis state her place of birth at the Buckinghamshire village of Lillingstone Lovell. If there had been a schism over the marriage, then this might prove that all had been forgiven (or indeed no such trauma had occurred), as Jessie's parents are to be found in the same village on the 1871 census. This seems highly suggestive that Jessie had gone to stay with her mother for the birth.

Meanwhile, in 1863 John was chosen to sit on a grand jury at the Quarter Sessions at Aylesbury, though it should be noted that this did not necessarily imply knowledge or competence, as the criteria for sitting on the jury was principally ascertained by a person’s income. He is also mentioned the same year as a Church Warden at Great Linford, and this appointment we might presume would have been on merit.

He was not however destined to stay for long, departing the village circa 1864/5. We seldom if ever gain an understanding from sale notices why someone was leaving, though the advertisement carried in the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of April 2nd, 1864, presents every appearance of a successful farm, describing the auction as an “important sale of livestock”, to include 140 couples of pure-bred Leicestershire sheep and a herd of cattle from North Wales stock. The farm is not named, and at “200 acres, well watered and fenced”, was somewhat larger than the 166 acres previously noted.

But despite this ambiguity, we can be sure that John was departing Wood Farm. An additional sales notice carried in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 6th, 1864, announced the sale of “100 acres of luxuriant growing crops of wheat and bean” at the Wood Farm, the sale under the direction of Mr John Orrell. John it stated was leaving at Michaelmas, this being the end of September.

But the story of the Orrels has an ambiguity to offer. The Bucks Herald of April 15th, 1865, contains an advertisement that not only continues to place John in the parish after the previously advertised date of his departure from Wood Farm, but seemingly at a different farm! The advertisement is for the sale by auction of “a rick of fine old hay” weighing 35 tons on the instructions of Mr Orrell, but the hay is located at "Lower Farm" (the only reference ever found to a farm of this name in the parish) with interested parties instructed, “to meet the Auctioneer at the Farmyard, near the Turnpike Gate.” The turnpike gate was the barrier at which persons wishing to use the road now known as the Newport Road had to pay a toll, and we know this was at the junction of the Newport Road and modern-day Marsh Drive, far from Wood Farm, but close to both the Black Horse Farm and Marsh Farm.

However, the Black Horse Farm was then under the tenancy of John Warren and Marsh Farm under the Sapwell family, so exactly where John’s 35 tons of hay were to be found must for now remain a matter of conjecture. One possibility to consider is that John had simply rented a field from another farmer and was selling off unused hay.

We do know that John subsequently moved his family to the aforementioned Lillingston Lovell, where a son, John was born in 1866, sadly passing away aged 16 months. Robert, another son, was born in 1867 and survived to adulthood. John Snr passed away just a few years later in 1870, followed by his wife in 1878.

The name John Orrell now enters the frame, and though he appears in no trade directory or census record for the parish, there is evidence to place him at Wood Farm in the early 1860s. John was born at Liverpool circa 1838, and aged 24 is listed on the 1861 census as a pupil lodging at a farm at Tickford, Newport Pagnell, presumably there to learn the trade. It was here that he must have met and courted Jessie Doig, the farmer’s daughter. Conceivably, the liaison was not warmly welcomed, as they married in London by license on November 5th, 1861, thereby evading the need to post banns at their local church.

Perhaps if they had indeed eloped this made a return to Tickford problematic, and a new home had to be found. The earliest report of John’s presence in Great Linford is from April 1862, when he became one of the parish overseers, a not uncommon appointment for a farmer. The couple's first child Francis Edith was baptised later in the year at Great Linford, on September 14th, 1862, but though the birth was also registered in the Newport Pagnell district (which covered Great Linford), later census records for Francis state her place of birth at the Buckinghamshire village of Lillingstone Lovell. If there had been a schism over the marriage, then this might prove that all had been forgiven (or indeed no such trauma had occurred), as Jessie's parents are to be found in the same village on the 1871 census. This seems highly suggestive that Jessie had gone to stay with her mother for the birth.

Meanwhile, in 1863 John was chosen to sit on a grand jury at the Quarter Sessions at Aylesbury, though it should be noted that this did not necessarily imply knowledge or competence, as the criteria for sitting on the jury was principally ascertained by a person’s income. He is also mentioned the same year as a Church Warden at Great Linford, and this appointment we might presume would have been on merit.

He was not however destined to stay for long, departing the village circa 1864/5. We seldom if ever gain an understanding from sale notices why someone was leaving, though the advertisement carried in the Buckingham Advertiser and Free Press of April 2nd, 1864, presents every appearance of a successful farm, describing the auction as an “important sale of livestock”, to include 140 couples of pure-bred Leicestershire sheep and a herd of cattle from North Wales stock. The farm is not named, and at “200 acres, well watered and fenced”, was somewhat larger than the 166 acres previously noted.

But despite this ambiguity, we can be sure that John was departing Wood Farm. An additional sales notice carried in Croydon's Weekly Standard of August 6th, 1864, announced the sale of “100 acres of luxuriant growing crops of wheat and bean” at the Wood Farm, the sale under the direction of Mr John Orrell. John it stated was leaving at Michaelmas, this being the end of September.

But the story of the Orrels has an ambiguity to offer. The Bucks Herald of April 15th, 1865, contains an advertisement that not only continues to place John in the parish after the previously advertised date of his departure from Wood Farm, but seemingly at a different farm! The advertisement is for the sale by auction of “a rick of fine old hay” weighing 35 tons on the instructions of Mr Orrell, but the hay is located at "Lower Farm" (the only reference ever found to a farm of this name in the parish) with interested parties instructed, “to meet the Auctioneer at the Farmyard, near the Turnpike Gate.” The turnpike gate was the barrier at which persons wishing to use the road now known as the Newport Road had to pay a toll, and we know this was at the junction of the Newport Road and modern-day Marsh Drive, far from Wood Farm, but close to both the Black Horse Farm and Marsh Farm.

However, the Black Horse Farm was then under the tenancy of John Warren and Marsh Farm under the Sapwell family, so exactly where John’s 35 tons of hay were to be found must for now remain a matter of conjecture. One possibility to consider is that John had simply rented a field from another farmer and was selling off unused hay.

We do know that John subsequently moved his family to the aforementioned Lillingston Lovell, where a son, John was born in 1866, sadly passing away aged 16 months. Robert, another son, was born in 1867 and survived to adulthood. John Snr passed away just a few years later in 1870, followed by his wife in 1878.

James Flowers Alcock

The next name we can associate with the Wood Farm is James Flowers Alcock, born 1826 at Sylesham in Northamptonshire. He was already living in the village at the time of the 1861 census, but residing at the farmhouse of Hannah Jarvis, Lodge Farm. He is listed as a servant, but with the occupation of Farm Bailiff, which means he was involved in collecting rents and generally managing an estate. This suggests he was working not for Hannah, but the Uthwatts.

The 1871 census tells us that he has made a career change and is now a farmer of 166 acres at "Wood House Farm", so though a slightly different name for the farm, once again an exact match to the acreage farmed by previous tenants. The Alcock tenancy was to be a brief one, as in 1874 we find a notice of James’s imminent departure published in the April 18th edition of Croydon's Weekly Standard. The sale announced is for “62 acres of capital grass keeping”, with the notice adding that he was planning to leave on September 29th. He was not it should be noted selling land, (it was not his to sell) but offering some of his fields to let for livestock to graze.

James is however still referred to as a resident of Great Linford in October of that same year, when he was sworn in as foreman of the grand jury at the Bucks Michaelmas Quarter Sessions. This however may have been nothing more than a holdover or error, as from subsequent newspaper reports, it is clear that James had moved to Thornborough in Buckinghamshire.

The 1871 census tells us that he has made a career change and is now a farmer of 166 acres at "Wood House Farm", so though a slightly different name for the farm, once again an exact match to the acreage farmed by previous tenants. The Alcock tenancy was to be a brief one, as in 1874 we find a notice of James’s imminent departure published in the April 18th edition of Croydon's Weekly Standard. The sale announced is for “62 acres of capital grass keeping”, with the notice adding that he was planning to leave on September 29th. He was not it should be noted selling land, (it was not his to sell) but offering some of his fields to let for livestock to graze.

James is however still referred to as a resident of Great Linford in October of that same year, when he was sworn in as foreman of the grand jury at the Bucks Michaelmas Quarter Sessions. This however may have been nothing more than a holdover or error, as from subsequent newspaper reports, it is clear that James had moved to Thornborough in Buckinghamshire.

Joseph Walters

The 1877 Kelly’s trade directory names several farmers in the parish, but all but one, Thomas Edward Townsend, can be connected to other farms. Though there was a large contingent of Townsends in Great Linford at this time, Thomas cannot be connected to this family, and no reference to him can be found in regard to Wood Farm, or indeed any other farm in the parish. But perhaps not uncoincidentally, a James Townsend is to be found on the 1881 census at a Wood Cottage, adjacent to the entry for Wood Farm. This is also the first proof that the farm came with accommodation for agricultural labourers.

The person found at Wood Farm on the 1881 census is Joseph Walters, however, he is described not as a farmer, but as a servant on a farm and an agricultural labourer. This would seem to mean, that at least on the night of the census, there was no tenant farmer present. As for Joseph Walters, he had been born in Great Linford circa 1834, and gives every appearance from other census records to have always been an agricultural labourer for hire.

As mentioned previously, the 1881 census also includes an entry for a “Wood Cottage.” Here were living two households, the aforementioned James Townsend, with his wife Cerdina and son Alfred, plus husband and wife James and Fanny Cotton. Both men are described as labourers, as is James’s son Alfred.

1881 also marked the year that the Ordnance Survey published the first 25 inch to the mile map of the parish, which shows the farmstead labelled as “Wood Farm”, something that we find consistently repeated for decades afterwards, up to and including the map produced in 1968. Click here to view the 1881 O.S. map.

The person found at Wood Farm on the 1881 census is Joseph Walters, however, he is described not as a farmer, but as a servant on a farm and an agricultural labourer. This would seem to mean, that at least on the night of the census, there was no tenant farmer present. As for Joseph Walters, he had been born in Great Linford circa 1834, and gives every appearance from other census records to have always been an agricultural labourer for hire.

As mentioned previously, the 1881 census also includes an entry for a “Wood Cottage.” Here were living two households, the aforementioned James Townsend, with his wife Cerdina and son Alfred, plus husband and wife James and Fanny Cotton. Both men are described as labourers, as is James’s son Alfred.

1881 also marked the year that the Ordnance Survey published the first 25 inch to the mile map of the parish, which shows the farmstead labelled as “Wood Farm”, something that we find consistently repeated for decades afterwards, up to and including the map produced in 1968. Click here to view the 1881 O.S. map.

Joseph Hendry

The 1870s and 1880s are in general a rather fallow period for any mention of Wood Farm in newspapers, and perhaps implying that the farmstead has been untenanted by a farmer for some time, the 1891 census reveals that living at the farmstead is the Uthwatts gamekeeper, Joseph Hendry, born 1836 in Hanworth, Norfolk. Perhaps Joseph was also farming the land, but it seems more likely that someone else had stepped in, as Joseph would have been kept busy with his gamekeeping duties, newspaper accounts of the period telling on several occasions of his dogged pursuit of poachers.

Joseph was married to Maria Daniels at Suffield in Norfolk, on September 22nd, 1855. They had at least three children, Alfred, Sarah and George, but none of their children were born at Great Linford or are present there on the day of 1891 census. However a granddaughter, Ethel, aged eight, is. She was the daughter of Alfred Hendry, who appears to have died in 1886. The fate of Alfred’s wife Mary has not been determined, but conceivably their daughter had been orphaned and she had come to live with her grandparents.

Joseph was married to Maria Daniels at Suffield in Norfolk, on September 22nd, 1855. They had at least three children, Alfred, Sarah and George, but none of their children were born at Great Linford or are present there on the day of 1891 census. However a granddaughter, Ethel, aged eight, is. She was the daughter of Alfred Hendry, who appears to have died in 1886. The fate of Alfred’s wife Mary has not been determined, but conceivably their daughter had been orphaned and she had come to live with her grandparents.

Robert Murray Wylie

Robert Murray Wylie was born October 14th, 1837, at Ochiltree, Ayrshire, in Scotland. He was married at Loughton in Buckinghamshire in 1863 to a Sarah Adnitt, and the couple went on to have at least 11 children together, all born in New Bradwell. In fact, Robert is never recorded living at Great Linford, and indeed we can find several references to him living at Bradwell Abbey Farm and another farmstead at Bradwell called The Limes.

However, a tenancy agreement (D_194/19) held at Buckinghamshire Archives provides solid evidence that Robert was working land associated with “Wood Farm” from at least December 1896. The agreement is between William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt and Robert and confirms that Robert was a resident of Bradwell, plus the very interesting revelation that the farmland extended across into Bradwell parish, though only for a little over six acres of pasture land. Most of the farm falling within Great Linford parish was divided between 103 acres of arable and 169 acres of pasture, a grand total of 278 acres.

The agreement includes a tally of the individual fields, which helpfully includes the Ordnance Survey field reference numbers, so it is interesting to see that the agreement included the farmstead. We have no firm evidence however that Robert and his family ever resided there; the 1901 census places the family at Bradwell, which seems to be their primary residence.

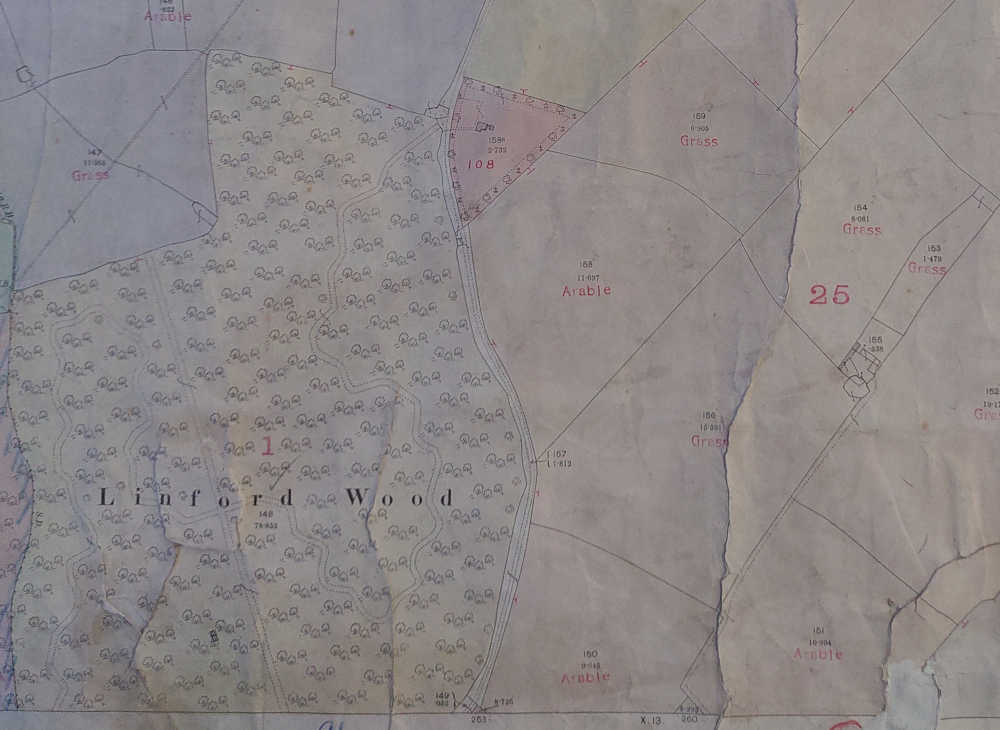

But regardless of where he and his family resided, Robert continued to farm his land at Wood Farm, a fact confirmed by the inclusion of his details on the 1910 valuation office survey map of the parish (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/9), though his occupancy has been somewhat reduced in extent to 148 acres. At present, only one portion of the relevant tax map, in rather poor condition, has been examined for this history, with his land labelled as #25.

However, a tenancy agreement (D_194/19) held at Buckinghamshire Archives provides solid evidence that Robert was working land associated with “Wood Farm” from at least December 1896. The agreement is between William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt and Robert and confirms that Robert was a resident of Bradwell, plus the very interesting revelation that the farmland extended across into Bradwell parish, though only for a little over six acres of pasture land. Most of the farm falling within Great Linford parish was divided between 103 acres of arable and 169 acres of pasture, a grand total of 278 acres.

The agreement includes a tally of the individual fields, which helpfully includes the Ordnance Survey field reference numbers, so it is interesting to see that the agreement included the farmstead. We have no firm evidence however that Robert and his family ever resided there; the 1901 census places the family at Bradwell, which seems to be their primary residence.

But regardless of where he and his family resided, Robert continued to farm his land at Wood Farm, a fact confirmed by the inclusion of his details on the 1910 valuation office survey map of the parish (Buckinghamshire Archives DVD/2/X/9), though his occupancy has been somewhat reduced in extent to 148 acres. At present, only one portion of the relevant tax map, in rather poor condition, has been examined for this history, with his land labelled as #25.

But within a few years the relationship with his landlord William Uthwatt was coming under great strain. A large body of correspondence exists between the two men and their representatives, which lays bare the dispute. On the side of Robert was a firm of land agents, J. C. H. Robinson, and for William Uthwatt, his solicitors W.B & W.R Bull of Newport Pagnell, as well as another land agent, J. R. Eve of Bedford. The correspondence between the various parties veers between good natured cut and thrust of negotiation, to exasperation and thinly veiled anger.

As noted previously in this history, an agreement had been entered into between William Uthwatt and Robert Wylie in 1896, but in 1915 that agreement was up for renewal, it appears on terms that Robert found unduly onerous. This is made abundantly clear in an illuminating exchange of letters (Buckinghamshire Archives D_194/20) between Robert and William Uthwatt’s solicitors, dated between August 30th and September 18th. In a letter of August 30th, the solicitors advise Robert that a new agreement has been drawn up and was available to view. Robert responded that he was then in Scotland but would return soon, but as the deadline of September 15th approached, several entreaties by the solicitors drew no response, until on the 17th, a short dismissive note was received, written by Robert’s son, John.

As noted previously in this history, an agreement had been entered into between William Uthwatt and Robert Wylie in 1896, but in 1915 that agreement was up for renewal, it appears on terms that Robert found unduly onerous. This is made abundantly clear in an illuminating exchange of letters (Buckinghamshire Archives D_194/20) between Robert and William Uthwatt’s solicitors, dated between August 30th and September 18th. In a letter of August 30th, the solicitors advise Robert that a new agreement has been drawn up and was available to view. Robert responded that he was then in Scotland but would return soon, but as the deadline of September 15th approached, several entreaties by the solicitors drew no response, until on the 17th, a short dismissive note was received, written by Robert’s son, John.

Gentlemen,

The conditions in the agreement sent by you were impossible in the 20th century therefore it was returned unsigned by the 15th, as requested. My father is still in Scotland, otherwise he would have written to you.

Yours faithfully

John A Wylie

Clearly the Wylies were of the opinion that the Uthwatts were making demands that belonged to another age, though it appears from the solicitor’s response on the 18th that the Wylies had simply returned the draft agreement “without note or comment.” The solicitors go on to state that since their client would not be offering better terms, they would have no choice but to give notice that the tenancy was to be terminated. William Uthwatt himself wasted no time in carrying out that threat, addressing a terse letter to Robert Wylie at The Limes, Bradwell. The typewritten document (Buckinghamshire Archives D 195/19) which was hand delivered on September 25th served notice on Robert to quit the Wood Farm within one year of its receipt.

A letter of October 9th, 1915, from the offices of William Uthwatt’s solicitors to H.T. Eve makes reference to the appointment of J.C.H Robinson as the representative of Robert Wylie, and that he had opened “his campaign”, likely a reference to a “claim for disturbance.” We do not have any clear particulars of the claim, but it was likely lodged under the terms of the Agricultural Holdings Act of 1908, which was frequently referenced in this period in regard to disputes between tenant farmers and landowners.

Much is made in the letters concerning the use to which individual fields were intended, the agreement of 1896 having stipulated which were to be arable, and which pasture, upon which hinged claims and counterclaims for payment. Arguments continued to be exchanged throughout the year, including a letter (Feb 11th, 1916) from J.C.E Robinson that rather sarcastically observes, “If Mr Uthwatt desires to find the Timber asked for, I believe he passes the farm at least 700 times a year and he can get out of any difficulty, if there is such, if he chooses.”

Another letter from the offices of J.C.H Robinson in late 1916 makes the interesting assertion that, “the house was condemned as unfit for habitation & want of water for household purposes.” Certainly, the local sanitary committee had their eye on the farm, as earlier that year the Wolverton Express of January 16th had reported on an order to make good on unspecified works, one would presume relating to sewage or some other matter of hygiene. This does seem to validate the suspicion that the farmhouse was sporadically occupied and Robert would have been much happier at his farmhouse in Bradwell.

Robert did have a year to vacate the farm by the terms of the tenancy, and on the very cusp of that moment, September 27th, 1916, served notice on William Uthwatt that he was making another claim for compensation. We can sure in this case that it was lodged under the Agricultural Holdings Act of 1908 and was likely an attempt by Robert to claim on improvements he had made to the farm out of his own pocket; after all, William Uthwatt would benefit materially from these improvements.

Robert died on April 10th, 1919, and though it is not clear who won this protracted war of words, we can dispel any notion that this was a David vs Goliath battle, with Robert as the improvised plucky tenant facing up to a powerful and wealthy landowner. While it is impossible to apportion blame for the dispute, Robert was clearly not a person to be trifled with and would not be intimidated. He was even appointed as a magistrate in 1916 and in his obituary was described as an alderman (a co-opted member of an English county or borough council, next in status to the Mayor) and a prominent member of the Agricultural Executive Committee based at Aylesbury. His funeral was a well-attended affair, with many notable mourners amongst the congregation, including it should be noted, a certain William Uthwatt.

A letter of October 9th, 1915, from the offices of William Uthwatt’s solicitors to H.T. Eve makes reference to the appointment of J.C.H Robinson as the representative of Robert Wylie, and that he had opened “his campaign”, likely a reference to a “claim for disturbance.” We do not have any clear particulars of the claim, but it was likely lodged under the terms of the Agricultural Holdings Act of 1908, which was frequently referenced in this period in regard to disputes between tenant farmers and landowners.

Much is made in the letters concerning the use to which individual fields were intended, the agreement of 1896 having stipulated which were to be arable, and which pasture, upon which hinged claims and counterclaims for payment. Arguments continued to be exchanged throughout the year, including a letter (Feb 11th, 1916) from J.C.E Robinson that rather sarcastically observes, “If Mr Uthwatt desires to find the Timber asked for, I believe he passes the farm at least 700 times a year and he can get out of any difficulty, if there is such, if he chooses.”

Another letter from the offices of J.C.H Robinson in late 1916 makes the interesting assertion that, “the house was condemned as unfit for habitation & want of water for household purposes.” Certainly, the local sanitary committee had their eye on the farm, as earlier that year the Wolverton Express of January 16th had reported on an order to make good on unspecified works, one would presume relating to sewage or some other matter of hygiene. This does seem to validate the suspicion that the farmhouse was sporadically occupied and Robert would have been much happier at his farmhouse in Bradwell.

Robert did have a year to vacate the farm by the terms of the tenancy, and on the very cusp of that moment, September 27th, 1916, served notice on William Uthwatt that he was making another claim for compensation. We can sure in this case that it was lodged under the Agricultural Holdings Act of 1908 and was likely an attempt by Robert to claim on improvements he had made to the farm out of his own pocket; after all, William Uthwatt would benefit materially from these improvements.

Robert died on April 10th, 1919, and though it is not clear who won this protracted war of words, we can dispel any notion that this was a David vs Goliath battle, with Robert as the improvised plucky tenant facing up to a powerful and wealthy landowner. While it is impossible to apportion blame for the dispute, Robert was clearly not a person to be trifled with and would not be intimidated. He was even appointed as a magistrate in 1916 and in his obituary was described as an alderman (a co-opted member of an English county or borough council, next in status to the Mayor) and a prominent member of the Agricultural Executive Committee based at Aylesbury. His funeral was a well-attended affair, with many notable mourners amongst the congregation, including it should be noted, a certain William Uthwatt.

Harry James West

Several letters dated April 1917 indicate a new tenant had been secured for Wood Farm, by the name of Mr E. Foolks of Old Bradwell. On the balance of probability, this was likely Edwin Foolks, born 1887 at Fenny Stratford, but if the agreement did come to fruition, it must have been a very short lived one, and no other mention has been discovered of the name in connection to Wood Farm.

The electoral rolls for 1918 provide new names at Wood Farm; Harry James West, his wife Charlotte and a son, Albert. Harry was born circa 1872 at Weston Underwood in Buckinghamshire, to Thomas (an agricultural labourer) and Sarah West. Upon the baptism of Harry’s son Albert in 1896, his occupation is given as shepherd, and by the time of the 1901 census (by which time the family had moved to Bradwell) he is employed as a horse keeper on a farm. Matters remain the same in 1911, that year's census continuing to record the same occupation and residence.

However, Harry does not appear to have secured the tenancy of Wood Farm, rather he is described on the 1921 census as was working as a “farmer foreman” in the direct employ of the Uthwatts of Great Linford Manor. We know this as usefully the 1921 census asks for the first time that the respondents provide details of their place of employment and name of employer. Hence it seems that at this time, the Uthwatts were drawing a direct income from the farm.

In 1923, the electoral rolls add another two occupants to Wood Farm, Francis Edward George, born in 1877, and his wife Eva, born in 1881. As to Harry James West, he and his family had moved out, and according to the 1924, 1928 and 1931 editions of the Kelly’s trade directory, had relocated to a Black Barn Farm in Great Linford. This farm is named in no other records that have been discovered, and so exactly where this was remains unknown; the electoral rolls for the same period place the West family on the east side of the High Street, which only serves to muddy the waters further; all the other farms in the parish then being accounted for.

Not much more can be divined about Wood Farm at this time, or the George family, though the electoral roll indicates that Francis was eligible as a juror, something that as previously noted, required a proof of income. The 1924 Kelly’s trade directory names Francis as the farmer of Wood Farm, as does the 1928 edition, but little else has been found of his origins or activities other than routine sales of crops. The couple departed the farm and the parish at some point between 1927 and 1928.

And who should we find back at Wood Farm in 1928, but Harry James West, who appears to have defied the odds and taken the tenancy for himself, though in the final event, not for long. The Wolverton Express of October 10th, 1930, carried an advertisement announcing his imminent departure, listing for sale 22 head of cattle, 80 sheep and lambs, five horses, 200 head of poultry and a copious list of agricultural implements, including a nearly new hay loader and a tractor and plough combined. The Northampton Herald of October 17th reported on a successfully concluded sale, including the amounts realised for many of the lots. For instance, a fresh-calved long horn and its calf went for £24 and 10 shillings, while the hay loader went for £15.

Later in the month, the Northampton Herald of October 31st, carried an advertisement listing the farm for let, with a description as follows: To let, with immediate possession, the Wood Farm, Great Linford, comprising house and buildings 1 acre, pasture 208 acres, arable 57 acres. It is not clear who next occupied the farm, but it does appear from several newspaper stories in early 1931, that an attempt had been made to interest the local authority in purchasing the farm to be offered to a tenant as a small holding, but this was declined as the farm was judged to be unsuitable for this purpose.

The electoral rolls for 1918 provide new names at Wood Farm; Harry James West, his wife Charlotte and a son, Albert. Harry was born circa 1872 at Weston Underwood in Buckinghamshire, to Thomas (an agricultural labourer) and Sarah West. Upon the baptism of Harry’s son Albert in 1896, his occupation is given as shepherd, and by the time of the 1901 census (by which time the family had moved to Bradwell) he is employed as a horse keeper on a farm. Matters remain the same in 1911, that year's census continuing to record the same occupation and residence.

However, Harry does not appear to have secured the tenancy of Wood Farm, rather he is described on the 1921 census as was working as a “farmer foreman” in the direct employ of the Uthwatts of Great Linford Manor. We know this as usefully the 1921 census asks for the first time that the respondents provide details of their place of employment and name of employer. Hence it seems that at this time, the Uthwatts were drawing a direct income from the farm.

In 1923, the electoral rolls add another two occupants to Wood Farm, Francis Edward George, born in 1877, and his wife Eva, born in 1881. As to Harry James West, he and his family had moved out, and according to the 1924, 1928 and 1931 editions of the Kelly’s trade directory, had relocated to a Black Barn Farm in Great Linford. This farm is named in no other records that have been discovered, and so exactly where this was remains unknown; the electoral rolls for the same period place the West family on the east side of the High Street, which only serves to muddy the waters further; all the other farms in the parish then being accounted for.

Not much more can be divined about Wood Farm at this time, or the George family, though the electoral roll indicates that Francis was eligible as a juror, something that as previously noted, required a proof of income. The 1924 Kelly’s trade directory names Francis as the farmer of Wood Farm, as does the 1928 edition, but little else has been found of his origins or activities other than routine sales of crops. The couple departed the farm and the parish at some point between 1927 and 1928.

And who should we find back at Wood Farm in 1928, but Harry James West, who appears to have defied the odds and taken the tenancy for himself, though in the final event, not for long. The Wolverton Express of October 10th, 1930, carried an advertisement announcing his imminent departure, listing for sale 22 head of cattle, 80 sheep and lambs, five horses, 200 head of poultry and a copious list of agricultural implements, including a nearly new hay loader and a tractor and plough combined. The Northampton Herald of October 17th reported on a successfully concluded sale, including the amounts realised for many of the lots. For instance, a fresh-calved long horn and its calf went for £24 and 10 shillings, while the hay loader went for £15.

Later in the month, the Northampton Herald of October 31st, carried an advertisement listing the farm for let, with a description as follows: To let, with immediate possession, the Wood Farm, Great Linford, comprising house and buildings 1 acre, pasture 208 acres, arable 57 acres. It is not clear who next occupied the farm, but it does appear from several newspaper stories in early 1931, that an attempt had been made to interest the local authority in purchasing the farm to be offered to a tenant as a small holding, but this was declined as the farm was judged to be unsuitable for this purpose.

Francis Thomas Beasley Hall

It might well be that Francis Thomas Beasley Hall was the last working farmer at Wood Farm, as we can trace his presence with reasonable confidence from his arrival circa 1931, when he first appears in a Kelly’s trade directory, until his passing at Great Linford in 1970. Francis was born on March 3rd, 1890, at Norton in Northamptonshire, to Owen and Sarah Hall, nee Beasley. His father was a farmer, and we find Francis still at Norton by the time of the 1921 census, where he is working as an agricultural tractor driver in the employ of his father. With Francis is his wife Mary Louisa, nee Holton, along with daughters Pearl and Christine, and son Ralph. How they then came to be at Wood Farm we do not know, but a number of newspaper stories in subsequent years reveal something of the family’s life on the farm, including a particularly harrowing tragedy.

Under the heading Money from Moles, we find a letter sent to the Fireside Topics section of the Daily Mirror of January 6th, 1934, written by 16-year-old Ralph Hall. Ralph tells how his dog Tiny, a Welsh Sheepdog, was proving a highly effective mole catcher, and had caught as many as 25 moles in as many minutes. Ralph was paid ½p each for each mole dispatched, and a penny each for the skins. With a tally of 400 skins, he was able to buy a bike with the proceeds.

Presaging much worse to come, Ralph was fined in August of 1936 for riding a motorcycle without insurance at Paulerspury. It was on perhaps the same motorcycle that his 18-year-old younger brother Donald was killed, just a stone’s throw from Wood Farm. As reported by the Northampton Mercury of August 16th, 1940, Donald had been riding on a motorcycle belonging to an unnamed brother, when he lost control and skidded into a tree, receiving fatal head wounds. The accident occurred just 400 yards from Wood Farm on a narrow bridle-road.

Fire was always an occupational hazard for farmers, and on the evening of Sunday May 5th, 1946, “two major pumps raced to Wood Farm, Great Linford, where they found a large thatched barn well alight.” The report in the Wolverton Express carried in their edition of the 10th further adds that the brigade was able to isolate several other ricks of hay, but serious damage was done to the barn, which contained dairy equipment.

There was happier news for the family in 1950, when on July 22nd, Neta, the youngest daughter of Francis and Mary was married at Brixworth to a Tom Smith. The notice places the Hall family still at Wood Farm. Mary Hall passed away on June 20th, 1958, her residence described as Wood Farm. Her obituary in the Bucks Standard of June 28th observes that she had been ill for a long time and that she had been born at Chetwode in Buckinghamshire. She was a member of the women's section of the British Legion, and "also helped in other local activities." Francis passed away on June 8th, 1970, and though his probate record places him at Wood Farm, a newspaper report of his death notes that he was resident on the High Street, at a "Wood Farm Cottage." The exact location of this cottage has yet to be ascertained. As recounted by the family, brothers Ralph and Alan Hall together managed the farm in its final years, before purchasing a small-holding near Boston, Lincolnshire.

Under the heading Money from Moles, we find a letter sent to the Fireside Topics section of the Daily Mirror of January 6th, 1934, written by 16-year-old Ralph Hall. Ralph tells how his dog Tiny, a Welsh Sheepdog, was proving a highly effective mole catcher, and had caught as many as 25 moles in as many minutes. Ralph was paid ½p each for each mole dispatched, and a penny each for the skins. With a tally of 400 skins, he was able to buy a bike with the proceeds.

Presaging much worse to come, Ralph was fined in August of 1936 for riding a motorcycle without insurance at Paulerspury. It was on perhaps the same motorcycle that his 18-year-old younger brother Donald was killed, just a stone’s throw from Wood Farm. As reported by the Northampton Mercury of August 16th, 1940, Donald had been riding on a motorcycle belonging to an unnamed brother, when he lost control and skidded into a tree, receiving fatal head wounds. The accident occurred just 400 yards from Wood Farm on a narrow bridle-road.

Fire was always an occupational hazard for farmers, and on the evening of Sunday May 5th, 1946, “two major pumps raced to Wood Farm, Great Linford, where they found a large thatched barn well alight.” The report in the Wolverton Express carried in their edition of the 10th further adds that the brigade was able to isolate several other ricks of hay, but serious damage was done to the barn, which contained dairy equipment.

There was happier news for the family in 1950, when on July 22nd, Neta, the youngest daughter of Francis and Mary was married at Brixworth to a Tom Smith. The notice places the Hall family still at Wood Farm. Mary Hall passed away on June 20th, 1958, her residence described as Wood Farm. Her obituary in the Bucks Standard of June 28th observes that she had been ill for a long time and that she had been born at Chetwode in Buckinghamshire. She was a member of the women's section of the British Legion, and "also helped in other local activities." Francis passed away on June 8th, 1970, and though his probate record places him at Wood Farm, a newspaper report of his death notes that he was resident on the High Street, at a "Wood Farm Cottage." The exact location of this cottage has yet to be ascertained. As recounted by the family, brothers Ralph and Alan Hall together managed the farm in its final years, before purchasing a small-holding near Boston, Lincolnshire.