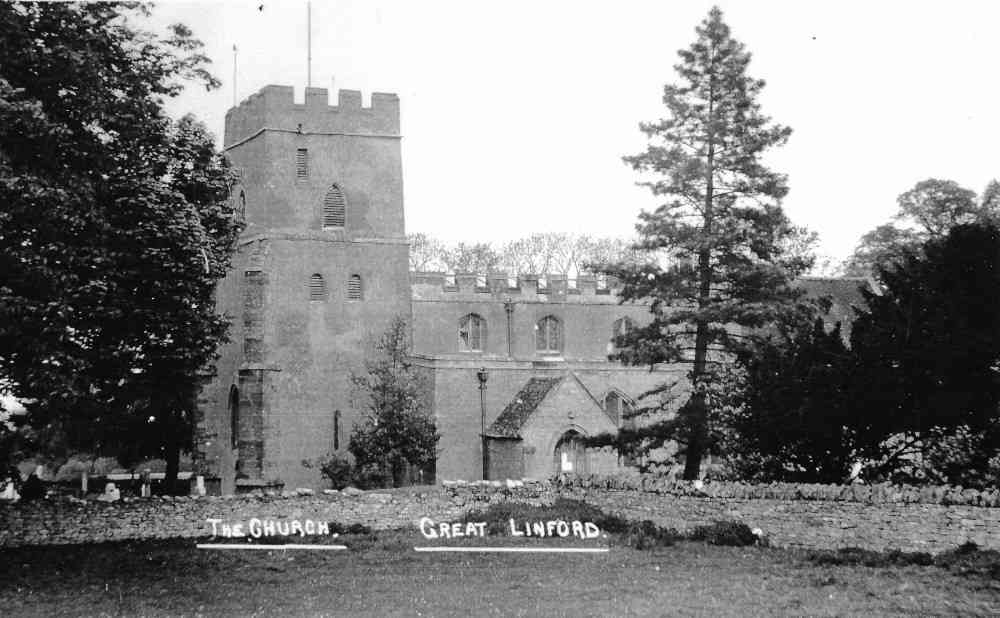

St. Andrew's Church, Great Linford

The visitor to St. Andrew’s Church, (named after one of the apostles of Jesus) will find an ancient building of considerable charm and character that has been much modified over the centuries. In 1980, an archaeological watching brief established during internal remodelling work allowed for some limited excavations; this found evidence for an older phase of construction on the site, comprising of a nave, which measured 21 feet by 33 feet 9 inches, along with a smaller 15 foot 9 inch long chancel. It was unclear if they were built together, or in two phases, but they are thought to be late Saxon or early Norman in date.

It is not uncommon to discover an earlier Saxon church beneath a newer one, but the discovery at Great Linford is considered significant, as it is the only one in Milton Keynes where definitive in situ evidence of late Saxon occupation has been discovered. 50 early to middle Saxon pottery shards (circa 450-850AD) were recovered from within the church as well as several fragments of iron and a chain link, a volume of finds substantially higher than could be expected from arable soil. A favourable comparison could then be made with contemporaneous buildings excavated at Pennyland. However, given that the excavation of the adjacent medieval manor house at Great Linford found nothing at all of Saxon origin, it would seem that any settlement in the area was of fairly limited extent.

At some time in the 12th century the present church tower was abutted to the earlier nave and chancel and the westernmost wall of the old Nave was demolished. However, the roofline survives within the east face of the Tower, within the present Nave roof. Over the following centuries, it is possible to trace numerous other demolitions, extensions and alterations to the fabric of the building, while the internal fixtures and fittings have also been much repaired and altered to accommodate changing tastes and uses. The church today consists of the tower, nave, chancel, south aisle and porch, north chapel and north porch, along with a recently added vestry.

Wall paintings

Medieval churches were typically a riot of colour, with elaborate painted imagery adorning the whitewashed or plastered walls. In a largely illiterate society these vivid paintings served to reinforce religious piety and observance, but most were destroyed or obscured by paint or plaster during the protestant reformation of the mid-sixteenth century as they were considered idolatrous. Sadly only the barest hints remain of the paintings in St. Andrews, such as a fragment of thirteenth century red scroll on the exposed parts of the tower arch. When the eighteenth century wooden panelling on the north wall of the nave was removed, at least three periods of painted decoration were discernible, of which the earliest was a fragment of inscribed scroll that points to the prior existence of a large image.

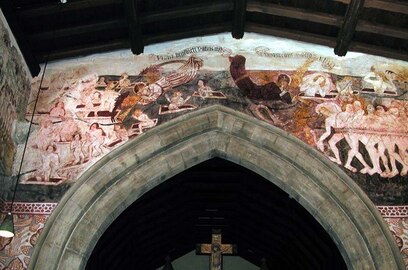

A typical medieval doom painting, as might have appeared in St. Andrews. John Salmon / St James the Great, South Leigh, Oxon - Wall painting

A typical medieval doom painting, as might have appeared in St. Andrews. John Salmon / St James the Great, South Leigh, Oxon - Wall painting

One of the most interesting fragments, as it is possible to make a guess as to its subject matter, was discovered on the west wall of the chancel, and (sadly no longer visible) depicted a series of red and yellow skeletal legs. It is speculated that this would have been an image of the three living and the three dead, intended as an allegorical warning against the emptiness of earthly ranks and riches.

On the chancel arch was yet another fragment, probably of a “doom painting”, which was a common depiction in medieval churches of the last judgement. These paintings were routinely bloodthirsty and frightening affairs, designed to instil a mortal terror of hell into the viewer and were sometimes purposefully positioned on the chancel arch so as to be constantly visible to the quivering congregation as they faced the altar.

On the chancel arch was yet another fragment, probably of a “doom painting”, which was a common depiction in medieval churches of the last judgement. These paintings were routinely bloodthirsty and frightening affairs, designed to instil a mortal terror of hell into the viewer and were sometimes purposefully positioned on the chancel arch so as to be constantly visible to the quivering congregation as they faced the altar.

|

Atop the fragmentary doom painting is a newer image, the coat of arms of King Charles II, unfortunately damaged when the coved ceiling was added in 1707. An image such of this was not added on a whim, but as a royal command. The practice had begun after the English Reformation and was intended to be a visible symbol that the temporal authority of the church no longer flowed from Rome but from the crown, though the practice fell in and out of favour over the years. The arms of King Charles II in St. Andrews was probably painted in the earliest years of his reign, which began in 1660, but this is not entirely certain as the date that originally adorned it has been damaged and only the numerals 1 and 6 survived, though having been concealed under the coved ceiling for almost 275 years, the colours remained remarkably vivid.

|

We do have an additional clue as to subject of one of the paintings in the church from the 1542 will of Elizabeth Malyn, which contains her request, “to be buried… before the pykture of our blessed lady”, so we can infer then with some confidence that there was also an image of the Virgin Mary within the church; her husband’s will makes a similar declaration. The Malyn family were clearly of significant stature in the village; they are attributed to a property and land on the High Street on the 1641 estate map, an echo of which still exists today in the property named Malins Farmhouse.

Roof carvings

Though the paintings have been lost, a number of interesting carvings have survived in the church, though due to renovations all are now out of sight and reach to the casual visitor. During the 1980s work the 18th century lathe and plaster coved ceiling was removed, revealing a late medieval timber roof of the King Post type; a King Post is a vertical beam extending up from a cross-beam to support the roof and is a common feature in medieval churches. Also revealed were carved bosses, these being located where the cross-members of the roof intersect. All but one of these carvings are of a typical floral (foliate) design for the period and some retain fragments of paint and gilding, but the most easterly boss is particularly special, as here the medieval carpenter has crafted an image of a Green Man, a woodland deity associated with pagan beliefs.

Medieval floor tiles

The medieval floor of the church would originally have been of compacted earth or mortar (or a mixture of the two), and would have been subject to much wear and tear, but the excavations of 1980 partly exposed a tile floor that was installed in the late 15th century at approximately the same time as seating was added. A section of the surviving flooring can still be viewed in the church today, accessible via a hatch in the floor.

The floor is constructed of small square decorated tiles, grouped in fours, forming a repeating mock circular inscription within a border. The tiles were made by coating a carved wooden block of the pattern with white pipe clay, which in turn was then stamped into a tile of red clay. The tiles were made at Little Brickhill, 7 miles to the south of Great Linford, and are of particular historical importance, as the only other surviving in situ example of these Brickhill tiles is to be found within the chapel at Bradwell Abbey. It has been estimated that some 2,500 tiles would have been required to pave the floor of St. Andrews and no doubt a considerable sum of money was expended, but amazingly we can not only identify the benefactor who paid for this work, but when it was carried out.

Embedded in in the nave floor is a brass monumental inscription bearing the following line:

Embedded in in the nave floor is a brass monumental inscription bearing the following line:

Here lieth I dowen under this stone Roger Hunt and Johane his wife. Of whose propre costs alone the Chirche was paved soon aft’ ye liffe

Hunt died in 1473, providing a high degree of confidence that the floor was paved at this time. For more on Hunt, see the Monumental Inscriptions page.

Stained glass windows

St. Andrews has of course a fine set of stained glass windows, though these are relatively modern except for a small surviving portion in one window, dated to medieval times. It seems likely that in 1707, a great deal of stained glass was destroyed in a major restoration of the church; large amounts of broken glass has been excavated from both under the church, and beneath what is now the Arts Centre carpark. More recent installations are well recorded, so that in some cases we know both the name of the maker and the benefactor who paid for the windows. A more detailed account of the history of the stained glass windows of St. Andrews can be found here.

Church bells

Quite rarely, Great Linford is blessed with a full set of six bells made at the same time by the same maker, and all still in regular use to this day. The bellfounder was a man called Joseph Eyre and the bells, (5 melted down and recast from an older set) were installed in 1756 and augmented by a new 6th bell paid for by Henry Uthwatt, the then Lord of the Manor. A fuller account of the history of bell ringing at Great Linford can be read here.

Change through the centuries

The upkeep and condition of the church would have been of considerable reflected prestige upon the Lords of the Manor, so we can speculate that much of the work carried out would have been financed by them, though we will see that eventually the cost of the upkeep would fall increasingly on public subscription. Here following are some significant changes made to St. Andrews over the centuries.

12th century

Speculation that a South Aisle was added to the earlier Nave. The south east external corner of the Tower retains a trace of the wall.

13th century

Nave widened and lengthened to the east by demolishing the north wall and the earlier chancel. A pointed Tower Arch was inserted in the late 13th century.

14th century

In the mid-14th century the south aisle was extended to the east and an arcade of three bays with octagonal columns added.

Toward the end of the century, a north porch and chapel was added to the nave. Built at approximately the same time as the medieval manor house (the remains are under the arts centre carpark), it is plausible to imagine that a rich new owner financed these alterations to the church, and that perhaps the chapel was a private place of worship for the manor house residents.

15th century

Improvements made to the Nave and Tower. The large western buttresses were primarily a fashionable addition rather than a structural necessity. So called two-light windows were inserted in the west wall of the tower and the nave had four clerestory windows added along each side; the word clerestory refers to the upper floor of a nave. An embattled parapet was added to conceal the roof line.

16th and 17th centuries

Little new work occurred during this period, though it appears that maintenance has been somewhat neglected, as a Bishop’s visitation of 1637 had a rather long litany of problems to be tackled.

12th century

Speculation that a South Aisle was added to the earlier Nave. The south east external corner of the Tower retains a trace of the wall.

13th century

Nave widened and lengthened to the east by demolishing the north wall and the earlier chancel. A pointed Tower Arch was inserted in the late 13th century.

14th century

In the mid-14th century the south aisle was extended to the east and an arcade of three bays with octagonal columns added.

Toward the end of the century, a north porch and chapel was added to the nave. Built at approximately the same time as the medieval manor house (the remains are under the arts centre carpark), it is plausible to imagine that a rich new owner financed these alterations to the church, and that perhaps the chapel was a private place of worship for the manor house residents.

15th century

Improvements made to the Nave and Tower. The large western buttresses were primarily a fashionable addition rather than a structural necessity. So called two-light windows were inserted in the west wall of the tower and the nave had four clerestory windows added along each side; the word clerestory refers to the upper floor of a nave. An embattled parapet was added to conceal the roof line.

16th and 17th centuries

Little new work occurred during this period, though it appears that maintenance has been somewhat neglected, as a Bishop’s visitation of 1637 had a rather long litany of problems to be tackled.

The Seates in the Church to be the Height of the partician. The readinge Seate to be removed to the Pulpitt and the Cover over it to be taken off, the Seates want bourdinge. A new Service booke and Bill. A table of degrees. The Instruccions. No hood. The chests to be new; The seate next to the front to be taken downe and made uniforme pavement in decay on the South side. The Crosse of the Steeple wanting. The church and the Steeple wants pargettinge; Some windows of the Chancell partlye boarded up.

Several of these words are in need of elaboration. English at the time had not been standardised, so pargettinge is likely to be a variation on the word pargeting, defined as a decorative relief work carried out in lime plaster which, when set and washed with lime, is indistinguishable from carved stone. This then would seem to indicate that the church was once adorned with a quite elaborate looking cross, atop a Steeple. While it might simply have been an artistic whim of the artist, the 1678 estate map does show the church with what looks to be steeple or cross.

Bourdinge is also an interesting word and seems likely to be derived from bord or bording, or in modern spelling, a board, obviously one of wood. Like pargettinge, bourdinge would seem to mean the act of carrying out the work, in this case presumably eplacing the wooden seating of the pews; one might imagine to the intense relief of the parishioners, who perhaps had suffered the indignity of splinters in the posterior at every sermon.

It is telling that this visitation occurred at the end of Richard Napier’s tenure, a Rector whom we know to be somewhat ambivalent about his ecclesiastical duties.

18th century

A new Lord of the Manor had arrived in 1678, the wealthy London merchant Sir William Prichard (also spelt Pritchard), who in knocking down the old medieval manor house and building a grand new house, (along with the Almshouses in the manor grounds) clearly had ambitious designs for a palatial estate. He passed away in 1705 and was buried in a family vault beneath the church, with the manor remaining in the occupation of his wife until her passing in 1718. She continued his charitable activities, including an agreement made in 1707 with the Rector John Coles for the Prichard estate to contribute the substantial sum of £1200 towards the renovation of the church.

Bourdinge is also an interesting word and seems likely to be derived from bord or bording, or in modern spelling, a board, obviously one of wood. Like pargettinge, bourdinge would seem to mean the act of carrying out the work, in this case presumably eplacing the wooden seating of the pews; one might imagine to the intense relief of the parishioners, who perhaps had suffered the indignity of splinters in the posterior at every sermon.

It is telling that this visitation occurred at the end of Richard Napier’s tenure, a Rector whom we know to be somewhat ambivalent about his ecclesiastical duties.

18th century

A new Lord of the Manor had arrived in 1678, the wealthy London merchant Sir William Prichard (also spelt Pritchard), who in knocking down the old medieval manor house and building a grand new house, (along with the Almshouses in the manor grounds) clearly had ambitious designs for a palatial estate. He passed away in 1705 and was buried in a family vault beneath the church, with the manor remaining in the occupation of his wife until her passing in 1718. She continued his charitable activities, including an agreement made in 1707 with the Rector John Coles for the Prichard estate to contribute the substantial sum of £1200 towards the renovation of the church.

It is agreed… that they… shall take down the Roof and walls of the said Chancel and Rebuild the same… before the feast day of St. Michael the Archangel in the year of our Lord God One thousand seven hundred and seven.

The feast day of St. Michael was held on September 27th, so if the schedule was adhered to, a great deal of work was completed by then. The Medieval Chancel was demolished and the original material was used to rebuild on the same foundations, while the Nave was completely refurbished. If they had not already succumbed to the Protestant zeal to remove them, this would be the time when the medieval wall paintings would have been entirely lost to view. It is thought that the South Aisle was also demolished and a new simple narrow replacement constructed, meaning the South Porch had to be remodelled. The Steeple was also likely lost at this time.

Recycling is hardly a new concept, and when the oak flooring laid in 1707 was removed, it was discovered that a number of the joists were timbers salvaged from the late 15th century pews.

In 1756, we have a new written account that tells us that the state of Church appears to be good. The Reverend William Cole (Rector to St Mary’s Church in Bletchley and antiquarian) wrote as follows after a visit.

Recycling is hardly a new concept, and when the oak flooring laid in 1707 was removed, it was discovered that a number of the joists were timbers salvaged from the late 15th century pews.

In 1756, we have a new written account that tells us that the state of Church appears to be good. The Reverend William Cole (Rector to St Mary’s Church in Bletchley and antiquarian) wrote as follows after a visit.

The Altar stands on an eminence of one step, neatly railed around and paved with black and white marble: The Altar piece being neat, having the decalogue painted on it. The Chancel is completely paved and uniform on both sides.

The decalogue is a term for the 10 commandments.

A parochial visitation carried out in 1828 found little of concern.

A parochial visitation carried out in 1828 found little of concern.

All things found to be in decent order (except that some Mortar Plastering had been placed on the tower which was ordered to be scrapped off). The tower repaired with Roman cement and coloured so as to correspond with the remainder.

19th century

Writing in his 1847 book, The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham, George Lipscomb provides an intriguing description of the tower.

Writing in his 1847 book, The History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham, George Lipscomb provides an intriguing description of the tower.

At the west end, is a square embattled tower, also covered with lead, which supports a pole, with a weather-cock at the top.

Clearly then the steeple is long gone, but the addition of a weather cock (alas now itself no more) is an interesting one. Why a Cockerel should have a particular association with weather vanes on church towers is said to be the a result of several Popes promoting the bird as a suitable symbol of Christianity, including Gregory I (590-604AD), such that by the 9th century, Pope Nicholas I ordered that the figure be placed atop every church steeple. The Cockerel is said to symbolise Christ, as at the Rooster’s crow, there is a transition from dark to light, however there are many alternative theories, one of which being that it represents an emblem of the vigilance of the clergy calling their congregation to prayer, whilst another suggests that the Cockerel actually represents the sun, and can be traced back to the Goths.

A refurbishment of the church took place in 1884, attributed by John Taylor in his book Cows before Concrete to the weight of the tower having unsettled the foundations, distorting the tower arch. A programme of fund raising was conducted over several years, with events held not just in Great Linford, but for instance in Newport Pagnell, when a Bazaar was held over two days in March of 1883 at the Masonic Hall. Vocal and instrumental music was promised, and intriguingly a Mrs. Jarley had kindly consented to exhibit her “Wonderful Waxworks.” Rather intriguingly, Mrs Jarley appears to have been quite well known, and well-travelled. She and her waxworks, which were actually moving automata, appear to have hailed from the USA!

A good account of the works carried out in the church appears in a newspaper report of August 16th, which also provides a colourful description of a bazaar held on Wednesday 13th in the rectory grounds to augment the restoration fund. The bazaar boasted a large marquee in which a number of stalls were set up, including one for toys and sweets and another manned by members of the North Bucks Beekeepers’ Association. Also to be found in the grounds was a flower stall, refreshments, and at the entrance to the Rectory Grounds, a “Fairy Pool”, which from the description appears to have been a variation on that perennial fairground attraction, a fishing game. A number of locally made innovations in the art of bee-keeping and chicken rearing were on display, and music was provided by the Newport Pagnell Church Institute Brass Band. The Bazaar made £60 in total, and prizes handed out included two lambs, a chair made from wood from the church and an oil painting donated by Mrs Uthwatt of the manor.

As to the refurbishment, the description is worth reproducing here in full, though it makes no reference to problems with the tower.

A refurbishment of the church took place in 1884, attributed by John Taylor in his book Cows before Concrete to the weight of the tower having unsettled the foundations, distorting the tower arch. A programme of fund raising was conducted over several years, with events held not just in Great Linford, but for instance in Newport Pagnell, when a Bazaar was held over two days in March of 1883 at the Masonic Hall. Vocal and instrumental music was promised, and intriguingly a Mrs. Jarley had kindly consented to exhibit her “Wonderful Waxworks.” Rather intriguingly, Mrs Jarley appears to have been quite well known, and well-travelled. She and her waxworks, which were actually moving automata, appear to have hailed from the USA!

A good account of the works carried out in the church appears in a newspaper report of August 16th, which also provides a colourful description of a bazaar held on Wednesday 13th in the rectory grounds to augment the restoration fund. The bazaar boasted a large marquee in which a number of stalls were set up, including one for toys and sweets and another manned by members of the North Bucks Beekeepers’ Association. Also to be found in the grounds was a flower stall, refreshments, and at the entrance to the Rectory Grounds, a “Fairy Pool”, which from the description appears to have been a variation on that perennial fairground attraction, a fishing game. A number of locally made innovations in the art of bee-keeping and chicken rearing were on display, and music was provided by the Newport Pagnell Church Institute Brass Band. The Bazaar made £60 in total, and prizes handed out included two lambs, a chair made from wood from the church and an oil painting donated by Mrs Uthwatt of the manor.

As to the refurbishment, the description is worth reproducing here in full, though it makes no reference to problems with the tower.

The church of St Andrew has been very substantially and neatly restored, and the interior now presents a very clean and comfortable appearance. Several slight additions and alterations have been made, but the general character of the edifice has not been interfered with. The deeply recessed doorway on north side, with groined ceiling, has been aptly converted into a unique robbing room and vestry, while the upper room formerly used for that purpose has been closed up, and the stairs leading to the same taken away, giving additional seating accommodation. The very unsightly gallery at the west end has also been removed, and the organ which was erected thereon placed in the chancel, where some new choir stalls have been fixed, after the modern style. The old high-backed pews have been substituted by seats of a more approved character. The work has been successfully and skilfully carried out by Messrs. Wilford Bros., of Newport Pagnell.

At the centre of the baptism ceremony is the font, and thanks to a newspaper article of September 27th, 1884 in Croydon’s Weekly News, we know that a new font had been presented to the church by the Clode Family. The article also provides some details of the fixtures and fittings; mentioning that the east-end had “been made very effective by a crimson dossal and side curtains, presented by friends of the rector.” A dossal was an ornamental cloth hung behind an altar in a church or at the sides of a chancel. Also added was “a very handsome plush and Utrecht velvet altar cloth, the gift of Mrs. Williams.” We also learn that Mrs. Uthwatt had given a handsome lectern. As a final fascinating detail, the church had newly installed a “Hadens’ heating apparatus.” Hadens, sometimes spelt Haydens, appears to have been a very successful business, and St. Andrews is not the only church we find them fitting heating for; it appears this was an underfloor heating system, which included the installation of an underground boiler room. The article provides a total cost for the refurbishment of £640, of which at the time £611 had been secured.

The earlier account of the renovations reproduced above mentions the relocation of the organ, which it appears proved an unsatisfactory arrangement. This was resolved a few years later in January of 1887, with the following story appearing in Croydon's Weekly Standard of the 8th, under the headline of “Opening of a new Organ.”

The earlier account of the renovations reproduced above mentions the relocation of the organ, which it appears proved an unsatisfactory arrangement. This was resolved a few years later in January of 1887, with the following story appearing in Croydon's Weekly Standard of the 8th, under the headline of “Opening of a new Organ.”

|

The first Sunday of the year 1887 will be remembered by many in the perish as the day on which the beautiful little organ recently erected by Mr. Atterton, of Leighton Buzzard, was used for the first time. When the church was restored in 1883, the old organ visa placed in the chancel, the gallery having been removed from the west end; but owing to its occupying so much space the appearance of the chancel was greatly marred/ Through the liberality of one whose name dues not transpire, the rector has been enabled to substitute the present instrument, which (being built on brackets and fitted into a recess in the wall) instead of detracting from the appearance of the east end rather adds to its finish and effect. The service in the afternoon was full choral. The chants, hymms, and psalms for the day were carefully rendered by the choir. Mr. Chetwynd presided at the organ. Alter the service Mr. B. Wilford, of Newport Pagnell, gave an organ recital, which was listened to with great attention and appreciation by the large congregation. The ringers, too, marked the occasion by a hearty peal on the bells as the congregation disperse.

|

Plans are now underway for a new restoration of the interior to meet the demands of modern congregations and the changing role of the Church; doubtless it will not be last in the long and fascinating history of St. Andrews.

This section could not have been completed without the prior work of Robert J. Williams, whose pamphlet a brief history of St. Andrews Church was invaluable in the preparation of this text, and is here gratefully acknowledged.

This section could not have been completed without the prior work of Robert J. Williams, whose pamphlet a brief history of St. Andrews Church was invaluable in the preparation of this text, and is here gratefully acknowledged.