Religion in Great Linford

Nestling in the north-west corner of the grounds of Great Linford Manor Park, the church of St. Andrews as we see it today is the result of centuries of modifications, both sympathetic and otherwise, but no matter how the fabric of the building has been altered over time (at one point it may for instance have boasted a steeple), a place of worship has stood firmly at the centre of village life for centuries. The earliest mention of a chapel appears in a charter dated 1151-4, however excavations beneath the floor of the nave in 1980 revealed the remains of an even earlier structure thought to have been late Saxon or early Norman in date.

The first recorded rector of St. Andrews was Geoffrey (or Galfridus) de Gibbewin in 1215. The journal Oxoniensia (vol I, 1936), gives an interesting account of Geoffrey and the de Gibbewin family, including the detail that at the time of his death in July 1235 he was insane, though he died not at Great Linford, but at Osney Abbey in Oxfordshire, having made way for a Richard Capellanus in 1220. Helpfully we have a comprehensive list of the past Rectors of Great Linford, which can be seen displayed inside the church, but which has also been transcribed for this website, along with some select biographies.

Christianity was of course an imported religion that arrived in the 7th and 8th centuries; prior to its introduction the religious character of the nation was very different, with Anglo Saxon Paganism dominating. These long held beliefs, centring on the worship of many deities and supernatural figures could not simply be erased by the arrival of Christianity and so continued for many centuries to be a part of people’s lives. That it continued to hold some sway in Great Linford seems incontrovertible, the proof for which is hidden within the roof of St. Andrews. Here was found during the renovations of 1980 the effigy of a Green Man, an eponymous image in the medieval period, representing a woodland deity associated with rebirth and spring.

Exactly why the Green Man should appear so often in medieval churches is a matter of conjecture, but it is fascinating to find Pagan beliefs coexisting side by side with Christianity. Perhaps the artisan who carved the Green Man at Great Linford believed that in doing so he was imbuing the wood with some mystical power that would grant long life and strength to the roof, but equally it may have been added with the tacit approval of the church. The adoption of Christianity was not without resistance and old ideas and traditions were hard to suppress, so the church took a pragmatic approach and typically incorporated Pagan beliefs and festivals into the Christian calendar as a way of persuading reluctant converts to accept the new faith. That a Pagan figure associated with rebirth and harvests would be borrowed and embraced by the Christian church seems hardly surprising.

Religious dissent

Religious observance in modern Britain is very much a matter of choice, we can elect to believe or not believe, and cannot in law be forced to adhere to any one faith or another. But this was not always the case. Coming after the English Reformation or 1532-34, which saw Henry VIII split from Rome and the Catholic Church, the 1558 Act of Uniformity enshrined in law the requirement to attend church once a week or be fined 12 pence – a considerable sum of money for a common person. Astoundingly, this law was not repealed until 1888, and though we have no specific cases to hand concerning Great Linford, it seems likely that in such a small community, you would have had to have been either very foolhardy or exceedingly brave and principled to take a stand against the established Church.

But there were those who rebelled, so called dissenters, who risked much to worship as they saw fit, and we do find some early evidence of their presence in Great Linford and the problems they faced, including the very real threat of prosecution. In 1669, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Gilbert Sheldon, who saw it as his mission to snuff out Presbyterian, Baptist and Quaker congregations, distributed a questionnaire to determine the extent of non-conformist gatherings in the country. If the reply from the Reverend John Fountaine is accurate (he may not have wanted to admit he had dissenters amongst his flock), the scourge of dissent had not yet penetrated far into Great Linford. The original spellings are retained in the following transcription.

But there were those who rebelled, so called dissenters, who risked much to worship as they saw fit, and we do find some early evidence of their presence in Great Linford and the problems they faced, including the very real threat of prosecution. In 1669, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Gilbert Sheldon, who saw it as his mission to snuff out Presbyterian, Baptist and Quaker congregations, distributed a questionnaire to determine the extent of non-conformist gatherings in the country. If the reply from the Reverend John Fountaine is accurate (he may not have wanted to admit he had dissenters amongst his flock), the scourge of dissent had not yet penetrated far into Great Linford. The original spellings are retained in the following transcription.

Honoured Sir, In obedience to the commands of my Lords Grace of Canterbury and the right Reverend Father in God the Bishopp of Lincoln, I doe certify that wee have noe conventicles or unlawfull assemblies in our towne or parish, only some few now and then stray abroade to unlawfull meetings in the neighbouring parishes, which are not above foure in number, and they are of very little esteeme, which with the care and assistance of the civill magistrate would easily bee prevented.

Ita Testor Johan Fountaine, Rector ibidem

It is interesting to note that Fountaine is at pains to point out that the dissenters are of low esteem, so he is making the point that no-one of importance or influence in the parish has strayed. It might also be speculated that those that were straying “abroad” as he puts it, may have been going to nearby Newport Pagnell, as the return for the town that same year goes into considerable detail about the activities of its dissenters, who appeared to be growing in number and well organised, despite there having been prosecutions inflicted upon them. That Fountaine ends his report with a not so veiled threat of his own, makes clear the pressures dissenters faced.

Yet despite any threats of legal action, by 1706 the dissenters are growing bolder, an observation made possible by another useful surviving religious record known as “visitations.” These questionnaires were ordered by Bishop William Wake and aimed to paint a picture of the conditions in each of his parishes, not just levels of dissent. Spread over several years, the visitations do however appear to show that dissent was on the rise in Great Linford. The 1706 visitation completed by the Reverend John Coles makes mention of “6 or 7 Presbyterians”, though it also observes that there is, “no meeting house in the parish” and no papists.

By 1709 the Presbyterians have made some further inroads. Of the 47 families in the village, then numbering about 193 persons, the Reverend Coles offers the following observation.

Yet despite any threats of legal action, by 1706 the dissenters are growing bolder, an observation made possible by another useful surviving religious record known as “visitations.” These questionnaires were ordered by Bishop William Wake and aimed to paint a picture of the conditions in each of his parishes, not just levels of dissent. Spread over several years, the visitations do however appear to show that dissent was on the rise in Great Linford. The 1706 visitation completed by the Reverend John Coles makes mention of “6 or 7 Presbyterians”, though it also observes that there is, “no meeting house in the parish” and no papists.

By 1709 the Presbyterians have made some further inroads. Of the 47 families in the village, then numbering about 193 persons, the Reverend Coles offers the following observation.

About 15 go to the Presbyterian, or Independent, meeting at Newport Pagnell; 8 others go to church in the morning, and to the meeting in the afternoon. These besides little children.

By 1712, Coles observes that 3 families are, “wholly dissenters; some in others; about 14 persons in all."

The reformation

In the aftermath of Henry VIII’s break with Rome, an inventory was ordered across the entire country in 1552, with the aim of seizing for the crown a great deal of the wealth held by parish churches. Though we have no way of knowing if the sequestration was actually carried out at Great Linford, we do have the following rather wonderful account of what was reported, here reproduced from “The Edwardian Inventories for Buckinghamshire”, published 1908.

Grete Lynford

[This] in[den]ture indentyd made [26 July 1552] of all the goodes .... perteyning to the parishe of Gret Lynford . . . betwyne [the same commissioners by virtue of the same commission] and Wylliam Kerne and Thomas Smythe .... all suche goodes [etc., as above.]

In primis five belles in the steple and a sauntes bell

Item a vestement of blwe velvet and an albe

Item a vestement of blew dammask and an albe

Item a cope of blewe velvet

Item a cope of old red lake parme velvet

Item ij chalesses of silver with patens

Item ij hand belles and a sacring bell

Item a crose of coper

Item ij candelstikes of brasse

Item a cofer of wood

Item a pewter shafte and a laten bason

[Two marks.]

The repression of the Catholic faith was to last centuries, and even when it began to wane, there were plenty of people who resisted any form of reconciliation. A newspaper report of February 14th, 1829 (carried in the Birmingham Journal), listed petitions to parliament that had been lodged from all over the country against “further concessions to the Roman Catholics.” Great Linford was included in this list. These petitions would have been raised in response to the Roman Catholic Relief Act, which against great opposition from King George IV and parliament had been passed in 1829. Repealing various repressive earlier laws such as the Test Act, which imposed a religious test on Roman Catholics and nonconformists wishing to hold public office, such that anyone who refused to take communion in the established Church of England would be excluded from such employment. It would for instance prevent a Catholic from standing as an MP.

But it was also perfectly right and proper for Dissenters to make use of the right of appeal to parliament, hence a year earlier in 1828 we find recorded in Volume 83 of the Journals of the House of Commons a long list of parish signatories, including Great Linford, calling for the repeal of the Test Act.

Change was clearly on the way, and at some pace. By 1813 a cottage was being used by dissenters to hold services, and by 1831 there were several venues in use; with a strong enough congregation that they could raise the funds to pay for and build a Congregational Chapel on Great Linford High Street in 1833, helped by a generous donation of land by a George Osbourne of Newport Pagnell. This clearly set alarm bells ringing, as the then curate of Great Linford, Henry Hughes issued a strongly worded letter that year to his parishioners, warning of the dangers to their souls should they stray from the established Church.

But the repeal of various repressive acts was the writing on the wall, and dissenters were clearly now a force to be reckoned with in the village, a fact amply borne out by the return provided in an 1851 census of places of religious worship that records a congregation of 81 persons; this out of a population of 486. Happily we know of course that the antipathy between the faiths would diminish over the years; an example can be found in 1946, when a Congregational minister departed with the thanks of various local churches, including the best wishes of Great Linford’s Anglican community.

But it was also perfectly right and proper for Dissenters to make use of the right of appeal to parliament, hence a year earlier in 1828 we find recorded in Volume 83 of the Journals of the House of Commons a long list of parish signatories, including Great Linford, calling for the repeal of the Test Act.

Change was clearly on the way, and at some pace. By 1813 a cottage was being used by dissenters to hold services, and by 1831 there were several venues in use; with a strong enough congregation that they could raise the funds to pay for and build a Congregational Chapel on Great Linford High Street in 1833, helped by a generous donation of land by a George Osbourne of Newport Pagnell. This clearly set alarm bells ringing, as the then curate of Great Linford, Henry Hughes issued a strongly worded letter that year to his parishioners, warning of the dangers to their souls should they stray from the established Church.

But the repeal of various repressive acts was the writing on the wall, and dissenters were clearly now a force to be reckoned with in the village, a fact amply borne out by the return provided in an 1851 census of places of religious worship that records a congregation of 81 persons; this out of a population of 486. Happily we know of course that the antipathy between the faiths would diminish over the years; an example can be found in 1946, when a Congregational minister departed with the thanks of various local churches, including the best wishes of Great Linford’s Anglican community.

When is a rector not a curate?

Delve into the religious history of any parish and you will encounter a number of different ecclesiastical titles, notably the Rector and the Curate, that are not entirely dissimilar in terms of their responsibilities, but which do nonetheless have an important distinction. The Rector of the parish received the living of the parish. This included tithes, set originally at 10% of the produce of the land, which could include crops, timber, fishing and even eggs. These tithes were often stored in a parish tithe barn. Alongside tithes were the revenues to be gained from the Glebe lands set aside for the Rector’s use, either to farm himself, or to sublet to tenants. A Curate on the other hand was appointed by the Rector (otherwise known as the Parish Priest) and his salary was generally paid from parish funds. Confusingly, we also find the word Clerk used interchangeably with that of Rector, as for instance, in a series of deeds held by Northampton Record office, Edmund Smyth, who was Rector at Great Linford between 1777-1789, is described in these documents as a Clerk.

The advowson

As was commonplace for many centuries throughout the country, the Lords of Great Linford Manor held considerable sway over ecclesiastical matters, as it was commonplace for men of their status to hold the advowson for the parish, literally the right to nominate the rector (the benefice) of their choice. The word Advowson is of French origin, coming originally from the Latin advocare, from vocare "to call" plus ad, "to, towards.” An Advowson can in essence then be thought of as a “summoning.” A tradition of a similar nature probably predates the Norman conquest of 1066.

But it was not always the case that the advowson was wielded by the sitting Lord of the Manor. George Lipscomb in his History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham published in 1847 asserts that this power for Great Linford had been held unbroken by its hereditary Lords until May 2nd, 1560, until Queen Elizabeth granted it to a William Button and Thomas Escourt, who appear to have been landed gentlemen from Wiltshire!

Without sight of the document Lipscomb alludes to, exactly why this happened is presently unclear, but Advowsons were treated in law the same way as property; they could be bought and sold. Hence we find a patent document from the Queen held by Somerset Heritage Centre dated December 21st 1559 that grants land and manorial titles to the same Button and Escourt in a number of counties including the advowson of Chyveley [Chievely] in Berkshire. The document notes the receipt to the exchequer of £1488 from William, so it seems entirely reasonable to suppose that money also changed hands in regard to the advowson of Great Linford. But why would anyone want to spend money on an Advowson, and what advantages did they bring to the owner?

For the Lord of the Manor, it has been suggested that in having the power to nominate a Rector, they could ensure that someone was appointed who would be pliant enough to represent their wishes; authority after all flowed from the pulpit, and a pious and compliant flock made for a peaceful and profitable manor. There was also the point that appointments could also be driven by politics, hence a Lord of a Manor might wish to appoint someone who shared his support of a particular political party.

It seems that Button and Escourt never wielded the power vested in them, but in 1590 we find that a London merchant named Edward Kimpton had acquired the advowson, which he used to appoint the Reverend Richard Napier. On the face of it, a London Merchant appointing a Rector to a sleepy Buckinghamshire village is passing strange, but it appears this was a family matter. The story is recounted in this site’s biography of the Reverend Richard Napier.

There was an additional reason a Lord of a Manor would have coveted an advowson, as there existed a pressing problem with a law called primogeniture, which meant that upon the death of a Lord, inheritance passed to the eldest male heir. Sons further down the pecking order were in need of an income, and the living of the Rectory was a nice little earner, hence we find in 1922 the Reverend Henry Andrewes Uthwatt receiving the living of Great Linford from his father, the Lord of the Manor Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt, though this would not happen again in the parish, as the primogeniture law was repealed just a few years later in 1925.

But it was not always the case that the advowson was wielded by the sitting Lord of the Manor. George Lipscomb in his History and Antiquities of the County of Buckingham published in 1847 asserts that this power for Great Linford had been held unbroken by its hereditary Lords until May 2nd, 1560, until Queen Elizabeth granted it to a William Button and Thomas Escourt, who appear to have been landed gentlemen from Wiltshire!

Without sight of the document Lipscomb alludes to, exactly why this happened is presently unclear, but Advowsons were treated in law the same way as property; they could be bought and sold. Hence we find a patent document from the Queen held by Somerset Heritage Centre dated December 21st 1559 that grants land and manorial titles to the same Button and Escourt in a number of counties including the advowson of Chyveley [Chievely] in Berkshire. The document notes the receipt to the exchequer of £1488 from William, so it seems entirely reasonable to suppose that money also changed hands in regard to the advowson of Great Linford. But why would anyone want to spend money on an Advowson, and what advantages did they bring to the owner?

For the Lord of the Manor, it has been suggested that in having the power to nominate a Rector, they could ensure that someone was appointed who would be pliant enough to represent their wishes; authority after all flowed from the pulpit, and a pious and compliant flock made for a peaceful and profitable manor. There was also the point that appointments could also be driven by politics, hence a Lord of a Manor might wish to appoint someone who shared his support of a particular political party.

It seems that Button and Escourt never wielded the power vested in them, but in 1590 we find that a London merchant named Edward Kimpton had acquired the advowson, which he used to appoint the Reverend Richard Napier. On the face of it, a London Merchant appointing a Rector to a sleepy Buckinghamshire village is passing strange, but it appears this was a family matter. The story is recounted in this site’s biography of the Reverend Richard Napier.

There was an additional reason a Lord of a Manor would have coveted an advowson, as there existed a pressing problem with a law called primogeniture, which meant that upon the death of a Lord, inheritance passed to the eldest male heir. Sons further down the pecking order were in need of an income, and the living of the Rectory was a nice little earner, hence we find in 1922 the Reverend Henry Andrewes Uthwatt receiving the living of Great Linford from his father, the Lord of the Manor Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt, though this would not happen again in the parish, as the primogeniture law was repealed just a few years later in 1925.

Pluralism

One of the more controversial practices as regards the granting of a living of a rectory was that the reverend in question might not actually reside in the parish, and in fact hold more than one living, something that came to be known as pluralism. Pluralism had long been a source of controversy, so for instance we find that several years after the Reverend Robert Chapman left Great Linford in 1762, he found that when wishing to accept the benefice of Ravenstone in Buckinghamshire, it was the holder of the Advowson, Daniel Finch, 8th Earl of Winchilsea, who insisted that Chapman dispose of his other benefice.

We might speculate that if the circumstances of one parish were more salubrious than the other, with a nicer house and a more genteel life to be enjoyed, then the rector might elect to appoint a curate to undertake his duties in the lesser place (or places), making only the occasional visit to his scattered flocks. Francis Litchfield, who was rector of Great Linford between 1838 and 1876, made his home at the rectory at Farthinghoe in Northamptonshire, where for instance we find him on the 1871 census with his wife and 6 servants. His appointment was not without controversy, with complaints levelled at his holding of more than one living causing a lively debate in the newspapers that rumbled on for some time; Litchfield also came under fire for having rented out the Rectory at Great Linford, rather than making it available to his curates.

It seems likely then that there was little love lost between Litchfield and his parishioners at Great Linford, and it was those curates he appointed, who by living in the parish, were more likely to earn the affection of their flocks. This appears to be the case with the Reverend John Marshall Webb, who must certainly have been a Litchfield appointee. On the occasion of his leaving Great Linford in 1872 after 19 years’ service, he was (as reported in the Bedfordshire Times & Independent newspaper) presented with a handsome piece of plate, with an illuminated address, while his wife received a case of very handsome silver fish-knives. The article concludes, “So general is the feeling of respect entertained in the parish toward Mr. and Mrs. Webb that all classes, without exception, willingly subscribed to the testimonial.”

However, not every Rector was absent. Lawson Shan, Edmund Smyth and his son William Smyth who succeeded him all lived in the Rectory, and clearly from the records left behind, we can conclude that all were active participants in parish life, as was the Reverend Sidney Herbert Williams, who played a significant role in the management of St. Andrew’s School on the High Street. It would therefore be disingenuous to suggest that every Reverend treated the living as a cash cow, and that for every Litchfield, there was a Shan, Smyth or Williams who were highly committed to both the spiritual and temporal well-being of their parishioners.

As a noteworthy final observation on this subject, absentee Rectors were not a new phenomenon, as a bishop’s visitation of 1519 found the church in “good order and Rector non residet (sic).”

We might speculate that if the circumstances of one parish were more salubrious than the other, with a nicer house and a more genteel life to be enjoyed, then the rector might elect to appoint a curate to undertake his duties in the lesser place (or places), making only the occasional visit to his scattered flocks. Francis Litchfield, who was rector of Great Linford between 1838 and 1876, made his home at the rectory at Farthinghoe in Northamptonshire, where for instance we find him on the 1871 census with his wife and 6 servants. His appointment was not without controversy, with complaints levelled at his holding of more than one living causing a lively debate in the newspapers that rumbled on for some time; Litchfield also came under fire for having rented out the Rectory at Great Linford, rather than making it available to his curates.

It seems likely then that there was little love lost between Litchfield and his parishioners at Great Linford, and it was those curates he appointed, who by living in the parish, were more likely to earn the affection of their flocks. This appears to be the case with the Reverend John Marshall Webb, who must certainly have been a Litchfield appointee. On the occasion of his leaving Great Linford in 1872 after 19 years’ service, he was (as reported in the Bedfordshire Times & Independent newspaper) presented with a handsome piece of plate, with an illuminated address, while his wife received a case of very handsome silver fish-knives. The article concludes, “So general is the feeling of respect entertained in the parish toward Mr. and Mrs. Webb that all classes, without exception, willingly subscribed to the testimonial.”

However, not every Rector was absent. Lawson Shan, Edmund Smyth and his son William Smyth who succeeded him all lived in the Rectory, and clearly from the records left behind, we can conclude that all were active participants in parish life, as was the Reverend Sidney Herbert Williams, who played a significant role in the management of St. Andrew’s School on the High Street. It would therefore be disingenuous to suggest that every Reverend treated the living as a cash cow, and that for every Litchfield, there was a Shan, Smyth or Williams who were highly committed to both the spiritual and temporal well-being of their parishioners.

As a noteworthy final observation on this subject, absentee Rectors were not a new phenomenon, as a bishop’s visitation of 1519 found the church in “good order and Rector non residet (sic).”

The worth of a living

It is possible to chart the worth of the living of Great Linford via a number of accounts, the earliest so far being discovered been the aforementioned visitation of 1706, which places “the value of the Rectory” at £95. The National Archives website provides a useful calculator that will convert old money into modern values, and this estimates that £95 would be the equivalent of £9,733, a salary a skilled labourer at the time would have taken just under a 1000 days to earn. By 1755 and the appointment of Robert Chapman, the value was put at £230; in modern terms about £23,000 per annum.

The living typically brought with it a property (the Rectory) and some land and its income, known as the Glebe. We see the echo of this on Great Linford High Street, with Glebe House. Lipscomb provides some specific figures for the extent of the Glebe land at Great Linford circa 1847. “The Rectory consists of fourteen acres of glebe land, in arable, with eleven acres of pasture, a yard and garden of about 2½ acres; and a claim of exemption from the tithes for the great meadow, having been allowed by the later Incumbents.” The Glebe land was quite likely to the rear of the property now known as Glebe House. The total according to the above figures would stand at just over 27 acres, which is corroborated by the 1851 census of places of worship, which provides a figure of 27 acres and a value of £400.

Jumping forward to 1876 and from a short newspaper notice on the appointment of Sydney Herbert Williams we learn that the living was much the same, with 26 acres of Glebe land and a worth of £400; in today’s money this would equate to something in the region of £26,000 per annum.

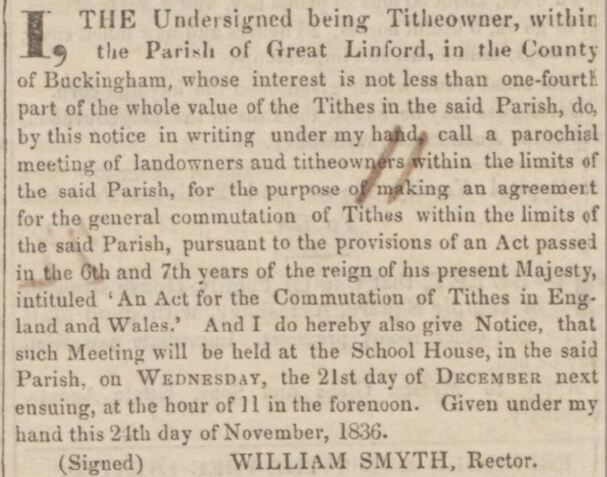

A significant change came about in the collection of Tithes with the passing of the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836, which sought to substitute payment in kind with a monetary equivalent. The change was probably welcomed by all involved as it aimed to simplify matters considerably, but the details had to be hammered out, hence we see that late in December 1836, William Smyth, Rector of Great Linford, called for a meeting to be held at the School House at 11am on the morning of Wednesday December 21st, 1836.

The living typically brought with it a property (the Rectory) and some land and its income, known as the Glebe. We see the echo of this on Great Linford High Street, with Glebe House. Lipscomb provides some specific figures for the extent of the Glebe land at Great Linford circa 1847. “The Rectory consists of fourteen acres of glebe land, in arable, with eleven acres of pasture, a yard and garden of about 2½ acres; and a claim of exemption from the tithes for the great meadow, having been allowed by the later Incumbents.” The Glebe land was quite likely to the rear of the property now known as Glebe House. The total according to the above figures would stand at just over 27 acres, which is corroborated by the 1851 census of places of worship, which provides a figure of 27 acres and a value of £400.

Jumping forward to 1876 and from a short newspaper notice on the appointment of Sydney Herbert Williams we learn that the living was much the same, with 26 acres of Glebe land and a worth of £400; in today’s money this would equate to something in the region of £26,000 per annum.

A significant change came about in the collection of Tithes with the passing of the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836, which sought to substitute payment in kind with a monetary equivalent. The change was probably welcomed by all involved as it aimed to simplify matters considerably, but the details had to be hammered out, hence we see that late in December 1836, William Smyth, Rector of Great Linford, called for a meeting to be held at the School House at 11am on the morning of Wednesday December 21st, 1836.

Church, state & judiciary

Step back in time and we find that the role of the clergy often extended far beyond dispensing spiritual guidance from the pulpit; frequently we find them also handing out summary justice from the bench. Francis Litchfield, who between 1838 and 1876 was the Rector of Great Linford (though resident permanently at Farthinghoe in Northamptonshire), was often to be found sitting on the bench at Brackley; similarly the Reverend William Andrewes Uthwatt sat on the bench at Aylesbury and Buckingham. His father Henry (also a Reverend) had inherited Great Linford Manor in 1800, and it was William who appears to have appointed Francis Litchfield to his position as Great Linford’s Rector.

As such William was seldom called upon to make judgement on cases related to Great Linford, but one example did occur on January 28th at the Petty Sessions held in Buckingham, when George Sapwell of Great Linford was charged with assaulting and beating his uncle, Joseph Sapwell, a resident of Buckingham. George was convicted and fined £2, 11 shillings and 6p, or one months imprisonment.

Church and politics were also intertwined, which is amply illustrated in an obituary to the Reverend Christopher Smyth, who between 1836 and 1838 had been Curate of Great Linford, though the Smyth family had already occupied the Rectory for two generations over a period spanning almost 70 years; Christopher was in fact the first cousin, once removed of the Reverend Edmund Smyth. Carried in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News of Saturday April 17th, 1897, the obituary describes the Smyths as, “an old established county family, which has always been on the side of the Conservative party.” Indeed, a Conservative Association was founded in Great Linford in 1889, and the then Rector, Sidney Herbert Williams was a significant figure in the organisation, as unsurprisingly were the Uthwatts. It is abundantly clear then that Rectors were but one element in a complex web of connections that brought together religious, political and judicial power; it was arguably something of a privileged old boys network, often also intertwined through marriage, with the patronage of the Lord of the Manor being the glue that held it all together.

As such William was seldom called upon to make judgement on cases related to Great Linford, but one example did occur on January 28th at the Petty Sessions held in Buckingham, when George Sapwell of Great Linford was charged with assaulting and beating his uncle, Joseph Sapwell, a resident of Buckingham. George was convicted and fined £2, 11 shillings and 6p, or one months imprisonment.

Church and politics were also intertwined, which is amply illustrated in an obituary to the Reverend Christopher Smyth, who between 1836 and 1838 had been Curate of Great Linford, though the Smyth family had already occupied the Rectory for two generations over a period spanning almost 70 years; Christopher was in fact the first cousin, once removed of the Reverend Edmund Smyth. Carried in the Bucks Advertiser & Aylesbury News of Saturday April 17th, 1897, the obituary describes the Smyths as, “an old established county family, which has always been on the side of the Conservative party.” Indeed, a Conservative Association was founded in Great Linford in 1889, and the then Rector, Sidney Herbert Williams was a significant figure in the organisation, as unsurprisingly were the Uthwatts. It is abundantly clear then that Rectors were but one element in a complex web of connections that brought together religious, political and judicial power; it was arguably something of a privileged old boys network, often also intertwined through marriage, with the patronage of the Lord of the Manor being the glue that held it all together.