|

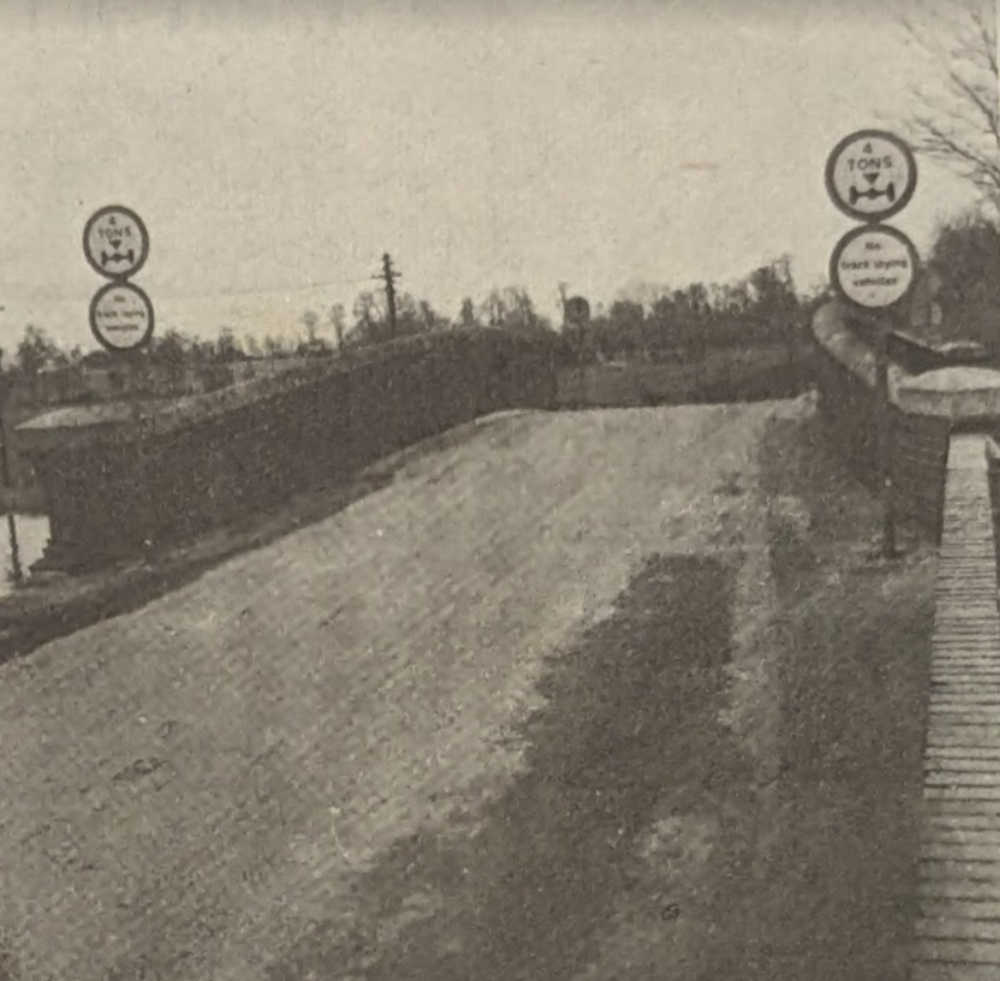

With the canal bridge presently closed for repairs, I am reminded that prior to the establishment of the city of Milton Keynes and its extensive road system, the closure of a bridge was a much more serious matter than it is today for the village. This was very much the case in February of 1969, with concerns raised as to the safety and weight bearing capacity of bridges connecting the village to the wider world. The Bucks Standard of Friday, February 28th, 1969, broke the story, with a headline posing the alarming question, was “Linford to be cut off?” Not quite, even a provisional newspaper knew the value of an eye-catching headline (and yes, my own headline is equally as guilty), but as the story elaborates, it was recently imposed weight restrictions on three crucial bridges that was the cause of concern. The matter had then been brought to the attention of Newport Pagnell Rural District Council by Stella Uthwatt, the elected village representative on the council. Stella was of course the last Uthwatt to hold title to the Manor House and gardens, and by all accounts still a force to be reckoned with in village life. Speaking at the council meeting of Wednesday 26th, Stella had pointed out that lorries over four tonne axle weight were not allowed into the village, and “this means that the whole farming community will come to a standstill and we will have difficulties getting food and beer supplies through.” Dramatically, she added, “The whole village is in great danger.” The clerk of the council, acknowledging Stella's concerns, explained that the safety of the bridges, and most specifically the main canal bridge (on Marsh Drive) had yet to be established. A letter had gone out to Bucks County Council, and reassurances had been made that the county surveyor had been tasked with resolving matters. Stella then asked if a Bailey Bridge could not be erected as a temporary measure but received a non-committal response.

There was good news in April, with a front-page story in the Bucks Standard of Friday 11th, headlined, “Relief of Great Linford Near – Beer wagon to roll again.” The story provides a great deal more detail as to the background to the crisis, explaining that it was a decision of the British Waterways Board that had imposed the four-tonne weight limit on the Marsh Drive bridge, while two tonne limits had been imposed on the bridges on the Willen and Woolstone roads. Bucks County Council had then formulated a plan to renovate the Marsh Drive bridge to allow a six-tonne weight limit, the county surveyor Eric Frankland predicting that, “this will allow vehicles such as the fire engine and brewery vehicles into Great Linford and should ease the situation considerably.” It is not recorded if the villagers felt access to beer or a fire engine was the higher priority, though the article states, “there were fears at one stage that no more supplies of beer would get through to the Nags Head.” However, as explained by the landlord Norman Carter, arrangements had been made that the pub was placed last on the delivery route, so the brewery lorry, by then greatly reduced in weight, could safely negotiate the bridge crossing. It was inconvenient, leading to late deliveries, so as Norman added, “I and the rest of the village too will be glad to know that the weight limit is to be raised, so we can get back to near normal again. This move will come at a good time too, just before the summer because we will need a lot more beer at the pub which will mean more deliveries.” But calamity; a happy ending was not so near. The Bucks Standard of May 30th carried the ominous headline, “Relief of Great Linford Delayed.” The problem now was that despite the council having agreed to do the work, the British Waterways Board had yet to grant permission for the work to proceed. Assurances were made that the council would pursue the Waterways Board for the permission, though as the article observed, “It looks as if the village may well have to wait a long time before the bridge is completely reconstructed to take all traffic, and the answer might rest with the new city. One of the early roads suggested in the interim report comes from Bletchley through the new city centre to join the main A422 road with a junction near Great Linford.” However, the prognosis of a long delay appears to have been premature, as in the July 4th edition of the Bucks Standard, came the welcome news that permission had been granted by British Waterways, and that the clerk of the council had offered the opinion that work would begin shortly. That no further news of delay appears to have been reported, indicates that the work did indeed take place before the close of 1969. Of course, now access to the village is well served by the new city grid road system, but it is fascinating to think that just a few decades ago, the village could, for want of a strong bridge, become so cut-off from the modern world, and a reliable supply of beer.

0 Comments

Great Linford has certainly had more than its fair share of famous faces pass through, though this is hardly surprising as for many years the Manor House served as a prestigious music recording studio, welcoming some of the top bands and singers in the world. But other names can be associated with the village from the world of show biz and television, some with more certainty than others, and two providing a link to one of the most infamous political scandals in British history!

Diana Dors Above: Diana Dors Above: Diana Dors

Diana Dors was an actress and glamour model, whose reputation as a sex symbol and lurid tabloid headlines disguise the fact that she was by all accounts a very accomplished actress, and that but for personal misfortunes and misjudgements, could very easily have secured her reputation as a serious artiste. Her name has come up in conversation often in connection to Great Linford, with older residents remembering her presence, but under exactly what circumstances she was here, and for how long she stayed, is a matter of speculation. What seems relatively certain is that she had a connection to the house known as The Mead.

It has been suggested that she owned The Mead, but it seems more likely that an aunt and uncle were living there in the 1950s or 1960s. Diana’s real surname was Fluck, while her mother’s maiden name was Payne, but neither name can be connected to The Mead. A name sounding something like Gutteridge has also been suggested, but again, a blank is drawn in trying to connect the name to the house. A person who remembers the owners of the house in the 1980s relates the understanding was held that Diana had owned it, and that it was her country get-away, but having run the theories past an expert on Diana Dors, a home in Great Linford is entirely unknown, and given that hers was a very public persona with numerous books written about her (and by her), the lack of evidence for her ownership seems compelling.

But despite the mystery of the ownership of The Mead, it does seem entirely likely from the recollections of residents of Great Linford, that Diana Dors had once turned heads in the village. Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice Davis

Beginning in 1961, John Profumo, the 46-year-old War Minister in the Conservative government of Harold McMillan, began an affair with a 19-year-old model and exotic dancer named Christine Keeler. At the same time, Keeler had entered into a relationship with an attaché at the Soviet embassy named Yevgeny Ivanov, a state of affairs with clear implications for national security. The exact circumstances behind Keeler’s brief relationship with Ivanov are subject to dispute; Keeler alleges in her biography that she was being set up and the intention was to generate blackmail material so that the Soviets could ascertain NATO nuclear plans in Europe. But what does this have to do with Great Linford?

The circumstances are certainly strange. The suggestion that Christine Keeler and her friend Mandy Rice Davies had visited Great Linford had been offered by a resident who remembered seeing them in the village, but is there any proof? Indirectly there is, and the trail starts at the manor house, which in 1956 had been occupied by a Michael Dibben, an entrepreneurial character who had developed a novel way of making casts of old garden statuary and then turning out copies. His unique selling point was that he had developed a way of cheaply reproducing items with a special concrete formula that simulated the patina of old garden ornaments. Chilstone proved very successful, and the company still exists to this day; you can even still buy “Great Linford” branded items. But how does this bring us closer to a connection to the Profumo Affair? To join the dots, we need to talk about Michael’s father, Horace Harold Dibben, known as “Hod” to his friends and acquaintances. Hod Dibben was an antique dealer who had made a name for himself as a nightclub owner in London, but his establishments were the more respectable front for the private parties he became infamous for, secret assignations where the rich and famous could shed their inhibitions. Christine Keeler denied ever attending one of these parties, but Mandy Rice Davies had, and in the highly charged atmosphere both girls inhabited, intrigue and blackmail went hand in hand, as did espionage. The name of Hod Dibben is one that exists on the periphery of the Profumo Affair, but it certainly gives credence to the idea that Keeler and Rice-Davies could have visited Great Linford as guests of the Dibbens. This is not to impugn the reputation of Michael Dibben, no concrete evidence points to any shenanigans at the manor, and indeed the story that has bee passed down suggests they stayed at Linford Lodge. Christine Keeler makes no mention of Great Linford in her biography, but perhaps we can speculate that as the Profumo Affair exploded into the public eye, Keeler and Rice-Davies sought a respite from the incessant press attention in a quiet little Buckinghamshire village. Great Linford Manor: The place to be

The tenue of the Dibben family certainly seems to have been a period when the manor was well known to various showbusiness luminaries of the time. It is recalled that the celebrity hairdresser Vidal Sassoon stayed at the manor, as did the actor Ian Hendry, well known for his role in the classic British drama The Avengers. Even more intriguingly, I am reliably informed that another visitor to the manor was Eddie Chapman, a well-known criminal and a wartime double agent, known to his handlers in the intelligence service as Zigzag.

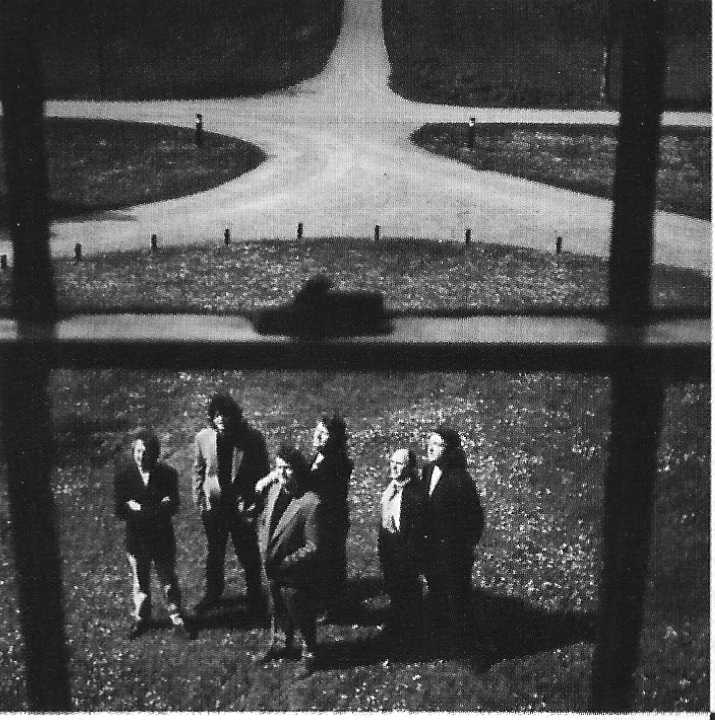

While on the run from the police, Chapman was caught and imprisoned in Jersey and was still incarcerated there when the Germans invaded in 1940. No doubt sensing an opportunity, Chapman offered his services as a spy and was subsequently parachuted into England, where he promptly handed himself in and turned double agent. After the war, he was involved in a number of businesses, and wrote his autobiography. Exactly what brought him to Great Linford is unknown, but it certainly adds a degree of intrigue to the history of the Manor. The cast and director of Suspect

Toward the end of 1969, a television crew descended on a snowy Great Linford to film a gritty crime drama called Suspect, which was to serve as a trial run for a short series called Armchair Cinema for Thames TV. Shot on film, which was an unusual extravagance at the time, Suspect and the stories that followed are well-regarded as programmes that served as a training ground for up-and-coming actors, writers and directors; one episode entitled Regan would be spung off into the immensely popular The Sweeney. Suspect was the work of Mike Hodges, who would go on to critical acclaim for his film Get Carter, which starred Michael Caine. Hodges is also well known for the camp cult classic, Flash Gordon.

Hodges wrote and directed Suspect, which filmed extensively inside the manor house, on the High Street and many other familiar locations in and around the village. The cast was led by Rachel Kempson, a RADA trained actress with many roles on stage and television to her name, including in later years Out of Africa and The Jewel in the Crown. She often co-starred with her husband Michael Redgrave, the couple founding an acting dynasty that included Vanessa Redgrave.

In Suspect, Rachel plays Phyllis Segal, who worries that the disappearance of her husband, coinciding with the apparent abduction of a local schoolgirl, must in some way be connected. But when the police arrive, she decides that she must keep up appearances at all costs and does all she can to deflect suspicion from her wayward spouse.

Above: Rachel kempson. Photo credit: Allan warren, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

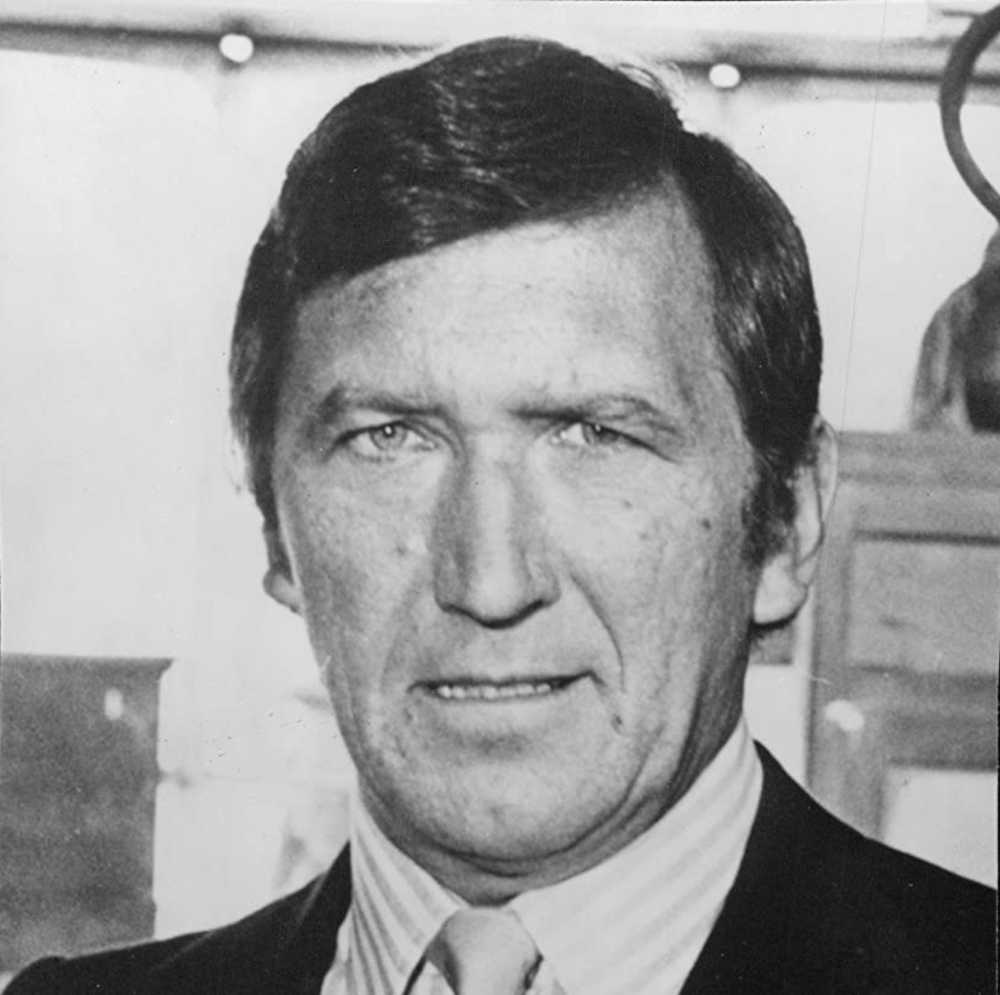

The police are led by Detective Inspector Barnes, played by George Sewell, whose craggy features graced many crime dramas of the period, playing characters on both sides of the law. He may be best remembered as Colonel Alec Freeman in Gerry Anderson’s live action UFO series. In Suspect, Sewell’s detective is a somewhat world-weary character, but determined to get his man.

Rounding out the main cast is Bryan Marshall, a stalwart of British television, but with roles also in movies like The Long Good Friday and The Spy Who Loved Me. Marshall plays the son of Phylis Segal, returning home to find the family’s life in turmoil.

Suspect is a particularly good crime drama, with plenty of suspense, and it is certainly fascinating to think that the village was once home to a television production of this nature. As of writing, the episode is available on YouTube.

|

About this blogA place for interesting nuggets of information about Great Linford. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

- Home

- About Great Linford

- Education

- Great LInford Manor Park

- Industry & Commerce

- Law & Order

- The Manor

-

People

- Harry Bartholomew

- The Cole Family

- Kizby and Kezia Rainbow >

- The Meads

- Reverend Richard Napier

-

Uthwatt, Kings Andrewes & Bouverie

>

- John Uthwat (?-1674)

- Daniel King (1670-1716)

- Richard Uthwatt (1658-1719)

- Richard Uthwatt (1699-1731)

- Thomas Uthwatt (1693-1754)

- Henry Uthwatt (1728-1757)

- Frances Uthwatt (1728-1800)

- Rev Henry Uthwatt Andrewes (1755-1812)

- Henry Andrewes Uthwatt (1787-1855)

- Reverend William Andrewes Uthwatt (1793-1877)

- Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt (1798-1885) >

- William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921)

- William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1898-1954)

- Stella Katherine Andrewes Uthwatt (1910-1996)

- Other notable Uthwatts

- The Ward & Robe Families

- Sir William Prichard and family >

- Places

- Politics

-

Religion

- Sport

- Visiting

- Blog

|

Winner of

2023 Robert Excell Heritage Award Presented by Milton Keynes Heritage Association |

- Home

- About Great Linford

- Education

- Great LInford Manor Park

- Industry & Commerce

- Law & Order

- The Manor

-

People

- Harry Bartholomew

- The Cole Family

- Kizby and Kezia Rainbow >

- The Meads

- Reverend Richard Napier

-

Uthwatt, Kings Andrewes & Bouverie

>

- John Uthwat (?-1674)

- Daniel King (1670-1716)

- Richard Uthwatt (1658-1719)

- Richard Uthwatt (1699-1731)

- Thomas Uthwatt (1693-1754)

- Henry Uthwatt (1728-1757)

- Frances Uthwatt (1728-1800)

- Rev Henry Uthwatt Andrewes (1755-1812)

- Henry Andrewes Uthwatt (1787-1855)

- Reverend William Andrewes Uthwatt (1793-1877)

- Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt (1798-1885) >

- William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921)

- William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1898-1954)

- Stella Katherine Andrewes Uthwatt (1910-1996)

- Other notable Uthwatts

- The Ward & Robe Families

- Sir William Prichard and family >

- Places

- Politics

-

Religion

- Sport

- Visiting

- Blog

RSS Feed

RSS Feed