|

With Halloween fast approaching, what better time to go in search of the spooky, the bizarre and the just plain unusual at Great Linford. The obvious starting point is ghost stories, but surprisingly for a village of such antiquity, there seem to be few restless spirits to disturb its peace. The website Spooky Isles offers a first-hand account of an encounter with a spectral girl at the Black Horse Inn and I have heard it suggested that The Nags Head has a resident ghost, but this seems to be the extent of any spectral shenanigans in the parish. Certainly, one might imagine that the centuries old manor house in the park would be a hotbed of paranormal activity; after all, we even have the required elements for a classic ghost story. Thomas Uthwatt was the Lord of the Manor in the 18th century, but was it seems a conflicted soul, who slit his own throat in 1754. However, there appear to be no reports of his tortured spirit haunting the house. The old rectory on the other hand can definitely be considered a good candidate for unusual goings on, especially as several of its former residents might reasonably be described as occultists, and in fact the Reverend Richard Napier was once accused of being a conjuror by one of his parishioners. Arriving in Great Linford in 1590, Richard Napier largely abdicated his official responsibilities as the parish priest, and concentrated his efforts on becoming an astrological doctor, drawing up complex horoscopes to divine the source of his patients’ afflictions. Among the more mundane aches, pains and sundry maladies he treated, he also encountered cases that suggested satanic powers at work, such as Thomas Richardson, who consulted Napier on July 14th, 1598, telling the doctor that his wife talked much of the devil and must be bewitched. To learn more about cases of witchcraft he treated, visit the Napier casebook website. Another resident of the rectory was Theodoricus Gravius, who as a refugee from war in Europe had found sanctuary with Richard Napier, and in due course would succeed him as rector of the parish. He was concerned not only with medicine, but was also engaged in chemical experimentation, complaining that he was unable to retrieve his laboratory equipment from Germany. One cannot help but wonder what fascinating investigations were undertaken within the walls of the rectory, perhaps even attempts to transform lead to gold! It is not difficult to imagine residents of the village looking on with suspicion at odd noises and noxious odours emanating from the rectory. Speaking of odd smells, in May of 1840, the Northampton Mercury reported on the excavation of a well on the estate of Henry Andrewes Uthwatt, where a “copious and permanent spring had been discovered, strongly impregnated with sulphurated hydrogen gas.” The article goes to say that the water could not be used for cooking purposes, “on account of the fetid odour which it exhales.” The article provides a considered scientific explanation for the phenomenon, but one can imagine that had the spring broke forth in Napier’s time, Great Linford might now be infamous as the location of a gate to hell. With farming being the predominant source of livelihoods in the parish, it is to be expected that odd stories concerning animals can be found. The newspaper Croydon's Weekly Standard of Saturday November 15th, 1884, featured a sad little tale of a curious deformity that had afflicted a piglet. GREAT LINFORD. STRANGE FREAK of NATURE. On Sunday last. November 9, a sow belonging to Mr. F. Kemp, of this village, gave birth to a litter of pigs, amongst which was one with two heads, each having ears. eyes, ect., perfect. The curious little animal, in consequence of no one being near at the time, was crushed to death by its dam. The full name of the owner of the piglet we can identify as likely to have been an engine fitter (doubtless employed at Wolverton Works) named Frederick Kemp, with the unfortunate birth having occurred in the vicinity of the Wharf. The reference to a dam having crushed to death the piglet is a word meaning the female parent. Like the previous story of the stinking well, had such a birth occurred in Napier’s time, it would doubtless have been ascribed to witchcraft, but by the 1800s, such notions had largely been dispelled. Minor curiosities of nature seemed a popular item for newspapers, such as an account from January 1869, concerning a shepherd named John Mapley, who was reported to have gathered up two mushrooms of unusual size, the largest measuring six and half images in diameter. Clearly a slow news day. Several newspapers of December 1886 carry a particular gruesome account of a freak accident that befell a Great Linford resident named Jospeh Fennemore, who was feeding his masters horses when one of them turned on him and bit his nose off. A doctor Rogers of Newport Pagnell attended but Joseph’s condition was considered a bad one, as his nose was bitten off level with his face. However, it seems that he must have rallied, as there is no record of a Joseph Fennemore dying at this time. Unhelpfully, there are two Joseph Fennemores who lived in the village in 1886, one who died in 1897, and his namesake son, who passed in 1912, so which of the two men was so hideously disfigured must remain a mystery. The village was in need of a Pied Piper in January of 1932, when a huge colony of rats was disturbed at Windmill Hill Farm, having been munching their way through a bean crop stored in the barn, perhaps the one still adjacent to the cricket pitch. Hundreds of rats poured forth, with a veritable massacre occurring over the next two days. Described as “the biggest slaughter of rats on one farm that has been known in North Bucks for many years”, the dead numbered in the region of 700, and “presented a gruesome spectacle laid out in rows in the field adjoining the barn.” Several reports of the calamitous effects of extreme weather in the parish can be found, including a case from July of 1865, when lightning struck a gang of workers and their horses on the construction site of the Grand Union Canal. The blast almost blinded one of the workers, and two horses were mortally injured. Almost a hundred years later, on Saturday March 1st, 1961, a tornado swept across the parish, having touched down at New Bradwell, before roaring through Great Linford, leaving a trail of damage in its wake. A particularly odd aspect of this story is the claim of one witness at New Bradwell that the tornado had been caused by a fireball he had witnessed pass overhead! Bad weather could also have its benefits. People who happened to be near the Black Horse inn on December 30th, 1926, were treated to a late Christmas dinner when a flock of partridges were caught up in a gale and crashed into telegraph wires, a total of ten birds falling dead to the ground, all of which were swiftly claimed for the pot. Under the headline, “Workmen’s Strange Discovery” the Northampton Mercury of March 26th, 1937, reported that a nest of “seven furry little animals” had been uncovered in the timber shed at Wolverton Railway Works, and suspecting they were otters, had requested the presence of William Uthwatt of the manor house, as he was master of the Bucks otter hound pack. On attending, he pronounced that they were not otters, but “some species of the fox tribe”, a rather curiously vague pronouncement from a seasoned huntsman. William took possession of the creatures, and no follow up story appears to have been filed that would clear up the mystery. Great Linford does have one Halloween tradition. For over a decade, the residents of 16 Wood Lane have been providing a Halloween maze experience, with live actors and plenty of thrills and chills. Further information can be found at halloweenscarymaze.com. If anyone reading this has any other spooky or strange Great Linford stories to share, please do comment below.

0 Comments

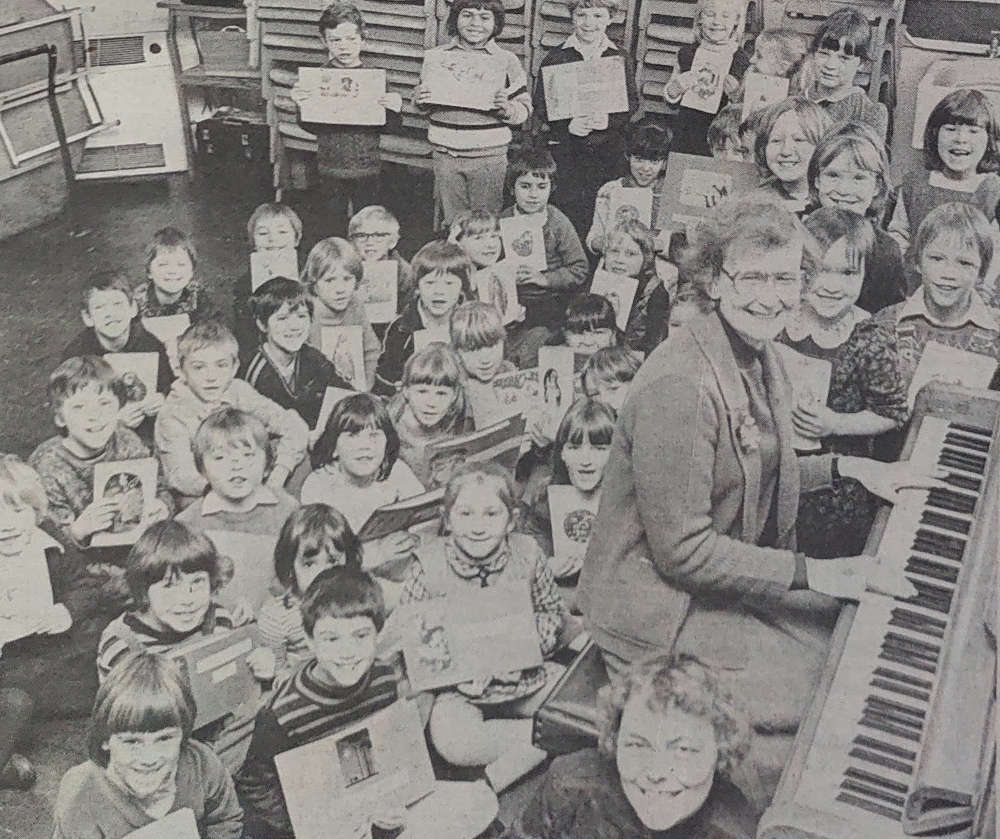

We can imagine that Christmas parties at the manor house were glamorous affairs; a gloriously bedecked and candlelit tree twinkling in a window, the discreet sound of an orchestra wafting into the snow shrouded park, the clink of champagne glasses and the murmur of genteel conversation, but what can we really discover of the realities of Christmas in the village at large? As it happens, whatever Christmas celebrations may have taken place at the manor house or any of the other grand houses in the village appear to have been entirely unremarked upon by the local press, but scouring the newspapers yields up some stories with festive spirit, and a few that might be better suited to Halloween. Christmas is of course a time for children, and so we find a report carried in the Bucks Standard of January 9th, 1892, telling us that on Saturday January 2nd, the children of the church Sunday School, numbering some 60 persons, were entertained to tea by the Rector and his wife, before been ushered into the classroom, where “a large Christmas tree had been decorated and laden with useful and fancy articles. Each child received one or two presents and an orange, and they evidently went away well pleased.” St. Andrew’s School on the High Street was opened in 1875 and a log book entry for December 23rd, 1886, records that Mrs Williams had visited the school, and given a petticoat to each of the girls, presumably as a Christmas gift; no record seems to exist of anything given to the boys. Mrs Williams would have been Ellen Maude Williams, the wife of the Rector, Sydney Herbert Williams. We have evidence of a white Christmas in 1890, as the closing remarks for the year make reference to the very poor attendance due to the snowy weather; similar conditions prevailed in 1896. The school was closed on December 21st, 1892 for a two week holiday, with a Christmas concert held that evening at 7pm. The last entries in the logbook for 1894 mentions that the children are engaged in preparing for “Christmas entertainments.” A similar entertainment took place the following year, as well as “social” on December 20th. A prize giving ceremony was conduced on the last day of the school year in 1910, December 21st, and following this, “there was a distribution of oranges to every scholar by Miss Christine Turnbull, and it having been announced that the holidays would extend to Monday, January 9th, the National Anthem was sung, and the children filed out of the school happy in the thought that for a fortnight they were to enjoy freedom from their books.” Christine was the daughter of the Rector, John Turnbull, and was again present at Christmas 1914, giving each child present an orange. Oddly, though the tradition of giving an orange at Christmas was clearly much cemented into the routine of school life and a school concert is often alluded to in the log books, there is no sign that nativity plays were routinely staged in this period; for instance in 1931 there is only mention of a “little breaking up concert.” That nativity plays have been a feature of the school year is however entirely certain, as in 1981, the school was showcased in a full page article in a local newspaper (possibly The Citizen), which makes mention of a nativity play. Changes in consumer behaviour is very much reflected by an advertisement carried in the Buckingham Advertiser of December 6th, 1930, offering cheap excursions to London for Christmas shopping, the fare from Great Linford railway station being 7 shillings. in December of 1950, there was also a very special traveller on the Newport Nobby, as the local train was affectionately called. Santa Claus himself set off from Great Linford to visit Newport Pagnell, greeted there to great excitement by hundreds of waiting children. Christmas day did not necessarily mean the cessation of all activity, both respectable and nefarious, and certainly some were up to no good. On the Christmas morning of 1907, Alfred Keech and William Richardson were apprehended on suspicion of trespassing in search of game at Great Linford. Police Constable Honour searched the men, and found the tools of their trade, freshly soiled pegs and wires used to snare rabbits. A few weeks later, the bench had evidently exhausted its supply of Christmas cheer, and both men were fined 10 shillings each, plus costs, or 14 days imprisonment if unable to pay.

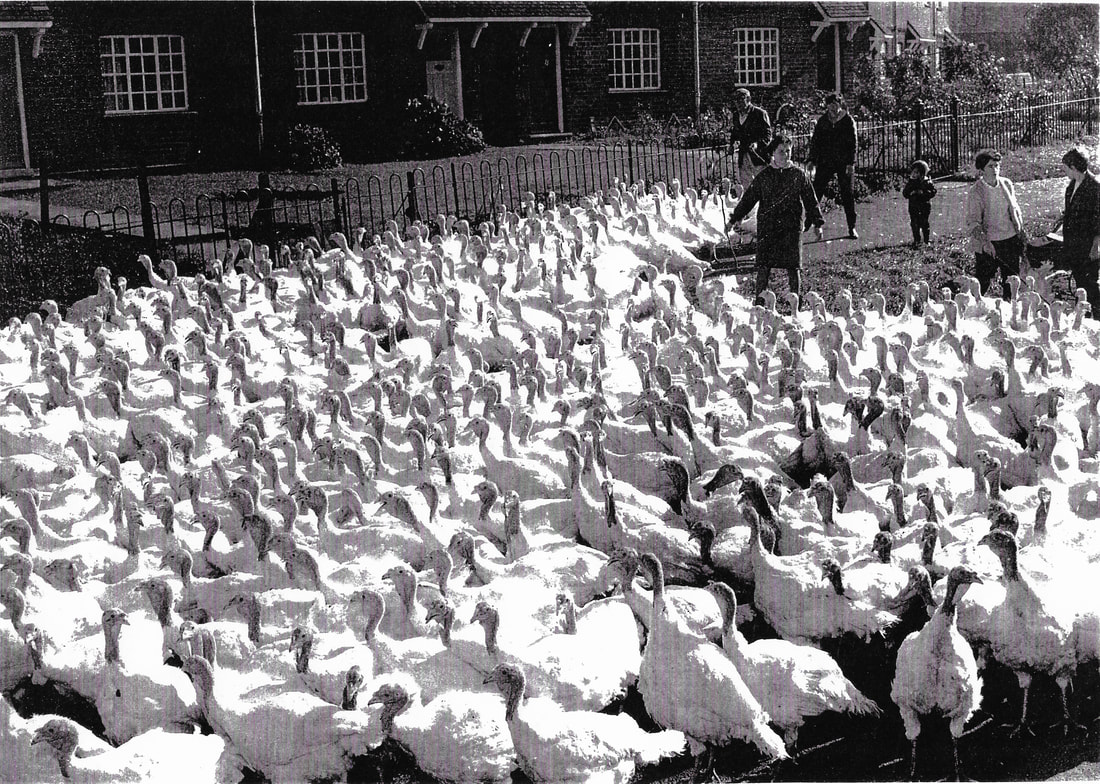

There was one traditional outdoor pursuit unlikely to attract the ire of the local constabulary, football. For instance, the local football team the Great Linford Hornets took to the field on Christmas Day 1935 against Salmons’ Sports and came away with a 2-1 win, though a return game scheduled for Boxing Day had to be abandoned owing to the state (unspecified) of the ground. Weddings were not unknown on Christmas Day, and indeed a number can be identified at Great Linford, the earliest of which was solemnised between John Webster and Ann Wilson in 1718. Another was that of Thomas Johnson, and Hannah Frost in 1802, and yet another was between Henry Reynolds, a brick maker, and Mary Dawby, taking place in 1858. You might imagine there was a romantic reason for marrying on Christmas Day, but in fact it was likely more out of necessity, as leave from work was a privilege few then enjoyed, and since Christmas Day and Boxing Day were the only two days of the year that bride and groom could reasonably both expect to have free, these days became popular with couples. Weddings led to children, and occasionally the happy occasion of a birth would coincide with the festive season. Such was case when Kathleen Rundle of The Wharf Inn delivered a daughter Tina on Christmas day 1959, though at 10 minutes past midnight, she was certainly cutting things fine. The Wharf Inn was also home at around this time to the Mathis family, one of whom was making a name for herself as a “local child star.” A year or two previously, Susan Mathis had appeared at the Scale Theatre, London, and the Hippodrome, Derby, performing a solo acrobatic dance. As a local celebrity, she was clearly in demand, and in 1958 put on a dance performance at a Christmas party for a Newport Pagnell old folks home. Various local organisations put on events over the Christmas period, including a dance held at the old Memorial Hall on December 13th, 1946, with music by a “modern dance band” called The Revellers. The proceeds from the dance (general admission 2 shillings, 6d, H.M Forces 1 shilling, 6d) was to go toward funding a children’s Christmas party. Some years earlier, representatives from the Great Linford branch of the Women’s Conservative Association were on hand for a Christmas Fair held in 1937, with villagers providing one of the stalls. Several familiar names from the village appear in the report carried in the Wolverton Express, including the Seamarks and a Mrs Uthwatt, whom we can take to be Caroline, the wife of the then Lord of the Manor, William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt. Thought it is entirely unfair to accuse the Uthwatts of a bah humbug attitude to Christmas, accounts of their activities during the festive season are almost entirely lacking across several hundred years of newspaper reports. It seems entirely likely that the Lords of the Manor would have felt a degree of obligation to provide some Christmas cheer to the villagers, but whatever form that took, we can only guess at, though several members of the family, including Stella Uthwatt, were guests at the school on a number of occasions to hand out prizes on the last day before Christmas, notably in 1925, when carols were sung. The only clear reference found to any Christmas largess is the supply of some gifts by Gerard Uthwatt to the patients at Renny Lodge Hospital, Newport Pagnell, in 1942. In the 1920s, the manor house was rented out to an American family called the Meads, and in 1927 the New Bradwell branch of the British Legion put on a children’s party, to which Mrs Mead donated a Christmas tree. In December of 1928, it was reported that carol singers visited the home of the Meads on the 22nd. The Meads were noted as attendees at the end of year festivities at St. Andrew’s School in the early 1930s, but here the supply of stories connected to the manor runs dry. Stories concerning the church of St. Andrews at Christmas are also surprisingly few and far between; one might have imagined that reports of Christmas services would have proven newsworthy, but only two accounts have been discovered. In 1883, a great deal of work had commenced to improve the structure and layout of the church, paid for by public subscription, and though by December the church was not fully open, it was announced that a Christmas day service was to be held. Another Christmas day story concerns the dedication of a new stained glass window in the church, the cost of which was paid for by a Joseph Bailey, in memory of his deceased son, William. The unveiling ceremony was carried out on Christmas day 1904, by the Reverend Turnbull. It does seem that there was once a traditional “feast day” held in honour of the patron saint of the church, held in the week before Christmas. This does not imply a celebratory meal, but rather a religious event. This feast day was still being celebrated at least as late as 1900. A rather odd story was published in Croydon's Weekly Standard newspaper of Saturday December 24th, 1910, concerning some visiting carolers from Stantonbury Girl’s Club. The carolers were on a tour of various villages in aid of charity, and the article reports that they had a very warm welcome in Old Bradwell, but sadly the reception in Great Linford was severely lacking in Christmas goodwill. As the article recounts, “the behaviour of a section of irresponsible youths was not of the character which one might expect.” The article does not elaborate on what this behaviour was, but it does seem to prove that delinquent behaviour is nothing new under the sun. Sadly, the festive period could have its fair share of tragedies, as for example the story of poor Agnes Ransley, who in 1930 visited the village of her birth for the holidays, and on Christmas day went to lay flowers on the grave of her parents, Frederick and Elizabeth Kemp. A trip on a grave stone and a fall resulted in a few minor injuries, but perhaps the shock was too much, as a week later she succumbed to a blood clot to the heart. As if that wasn’t a tragic enough story, a fatal accident occurred in the early hours of Christmas day 1941 to a solider on leave. 33 Year old Percy Richard Abel Turner was walking home to Great Linford after visiting New Bradwell when he and another solider were struck by a car. Percy died a few hours later at Northampton hospital, while his friend was severely injured. This being a post about Christmas, it seems entirely apt to close with a note on the considerable connection the village once enjoyed with the Turkey trade. This business was based at Church Farm on the High Street. The undated photo below shows Turkeys being driven to market on the High Street. |

About this blogA place for interesting nuggets of information about Great Linford. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

- Home

- About Great Linford

- Education

- Great LInford Manor Park

- Industry & Commerce

- Law & Order

- The Manor

-

People

- Harry Bartholomew

- The Cole Family

- Kizby and Kezia Rainbow >

- The Meads

- Reverend Richard Napier

-

Uthwatt, Kings Andrewes & Bouverie

>

- John Uthwat (?-1674)

- Daniel King (1670-1716)

- Richard Uthwatt (1658-1719)

- Richard Uthwatt (1699-1731)

- Thomas Uthwatt (1693-1754)

- Henry Uthwatt (1728-1757)

- Frances Uthwatt (1728-1800)

- Rev Henry Uthwatt Andrewes (1755-1812)

- Henry Andrewes Uthwatt (1787-1855)

- Reverend William Andrewes Uthwatt (1793-1877)

- Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt (1798-1885) >

- William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921)

- William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1898-1954)

- Stella Katherine Andrewes Uthwatt (1910-1996)

- Other notable Uthwatts

- The Ward & Robe Families

- Sir William Prichard and family >

- Places

- Politics

-

Religion

- Sport

- Visiting

- Blog

|

Winner of

2023 Robert Excell Heritage Award Presented by Milton Keynes Heritage Association |

- Home

- About Great Linford

- Education

- Great LInford Manor Park

- Industry & Commerce

- Law & Order

- The Manor

-

People

- Harry Bartholomew

- The Cole Family

- Kizby and Kezia Rainbow >

- The Meads

- Reverend Richard Napier

-

Uthwatt, Kings Andrewes & Bouverie

>

- John Uthwat (?-1674)

- Daniel King (1670-1716)

- Richard Uthwatt (1658-1719)

- Richard Uthwatt (1699-1731)

- Thomas Uthwatt (1693-1754)

- Henry Uthwatt (1728-1757)

- Frances Uthwatt (1728-1800)

- Rev Henry Uthwatt Andrewes (1755-1812)

- Henry Andrewes Uthwatt (1787-1855)

- Reverend William Andrewes Uthwatt (1793-1877)

- Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt (1798-1885) >

- William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921)

- William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1898-1954)

- Stella Katherine Andrewes Uthwatt (1910-1996)

- Other notable Uthwatts

- The Ward & Robe Families

- Sir William Prichard and family >

- Places

- Politics

-

Religion

- Sport

- Visiting

- Blog

RSS Feed

RSS Feed