|

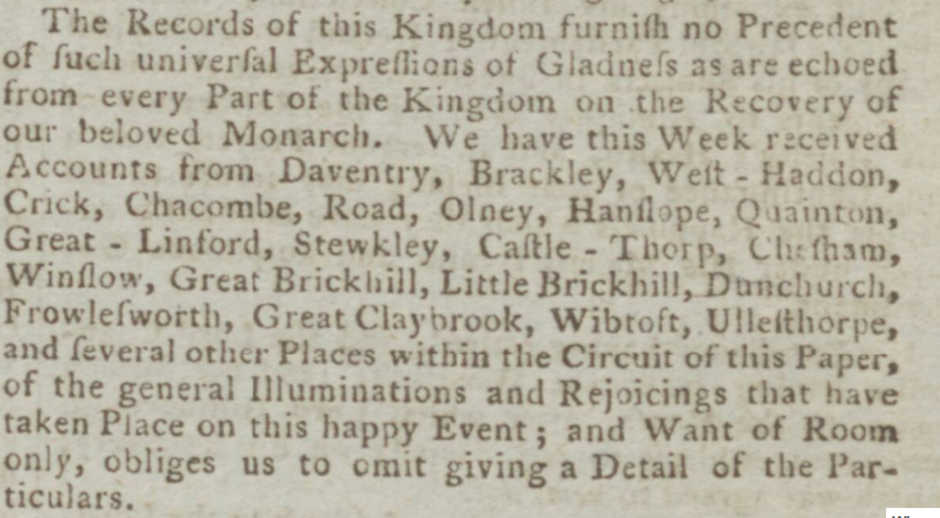

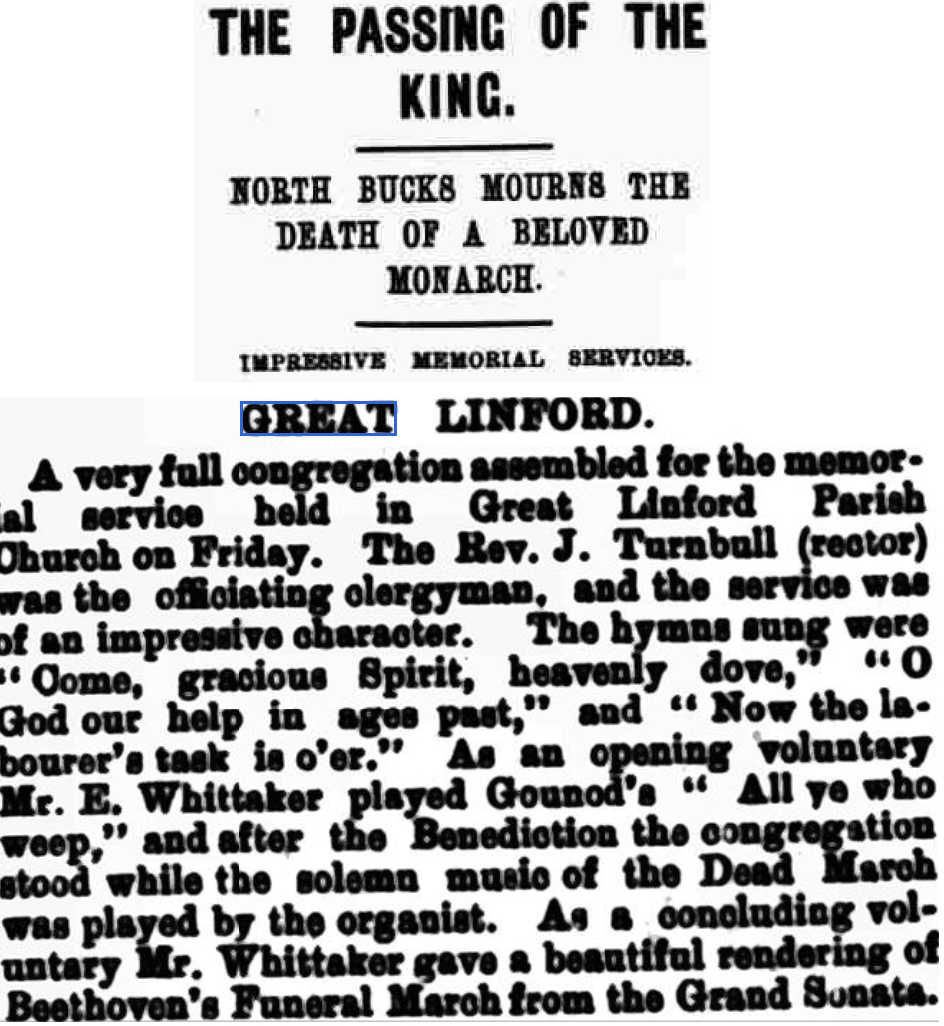

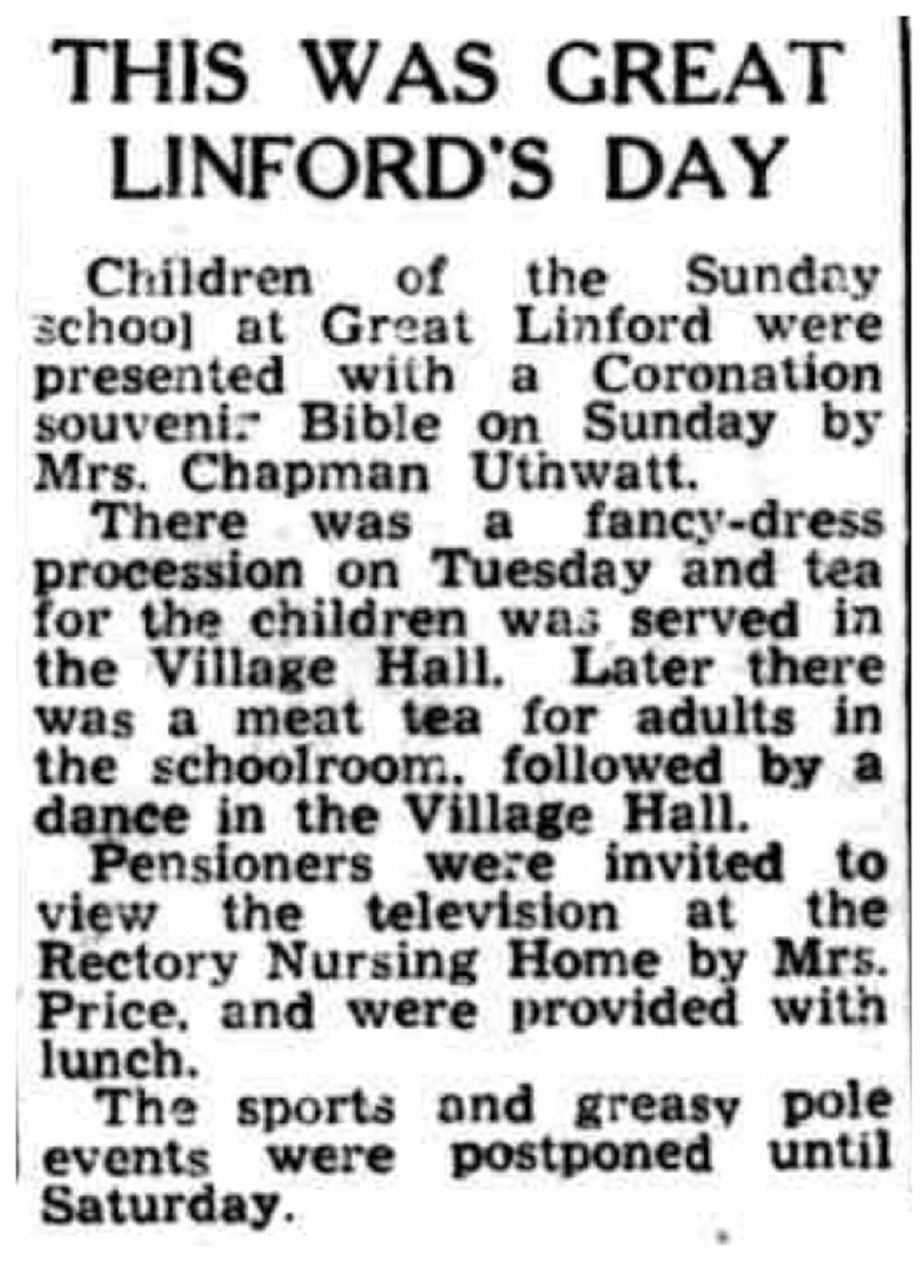

With the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee falling in June 2022, it seems a good time to dig into the history of Great Linford and see what connections to royalty can be discovered. Unsurprisingly, the manor estate has various royal connections, as in typical fashion it became a political football to be handed out (and taken away) on the whim and caprice of monarchs. For more details on these royal shenanigans, please refer to the history of Great Linford manor elsewhere on this site. The oldest in situ reference to royalty can be found within St. Andrew's church, though sadly the original is no longer visible to the public. This is the coat of arms of King Charles II, probably painted in the earliest years of his reign circa 1660. For more about this, please refer to the history of St. Andrew's Church page on this website. A very visible reminder of a royal connection can however still be seen in Great Linford Manor Park, the work of Sir William Prichard, who purchased the estate from the bankrupt Napier family in 1678. Prichard was a prominent supporter of the Protestant William and Mary of Orange of Holland, who had been installed on the British throne in 1689 to counter the perceived threat of Catholicism under the deposed King James. Prichard had co-authored a letter of welcome to William and Mary, and most significantly, the almshouses and school he caused to be built in the manor grounds have a distinctly Dutch feel to their architecture. This was clearly a calculated nod to his new monarchs, though one cannot help but wonder how, having spent so much time and effort on their construction, he made the King aware of his rather ostentatious gesture. Did he have them sketched, or painted? Mary had died in 1694, before the almshouses and school were built circa 1700, and William of Orange died in March of 1702, so perhaps at a pinch he might have been persuaded to visit. It’s certainly fun to imagine a royal visit, but it’s probably very unlikely to have ever happened. A royal through-trainThere is certainly no record to be found of a royal visit to the village or manor house at any time (I wonder if the Uthwatts ever issued an invitation?), but a minor royal did pass through the parish by train on May 21st, 1909. The personage in question was Her Royal Highness Princess Helena Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria; the family would not of course adopt the name Windsor until the eve of the First World War. The princess was on her way to attend a League of Mercy meeting in Newport Pagnell, an organisation founded by Queen Victoria to support charity hospitals. The accounts carried in newspapers tell of crowds on the platform at Great Linford, who cheered heartily as the train passed through. This fleeting visit appears then to be the closest brush Great Linford has had with royalty, though our present Queen has been close on several occasions, once in 1948 when she visited Wolverton Works and again in 1966 when she and Prince Phillip visited Newport Pagnell. A further visit to the then “new city” of Milton Keynes occurred in 1979. As can be seen from the following picture, thought to have been taken during the latter visit, the children of Great Linford appear to have travelled to see the queen. The madness of King GeorgeHowever, though we cannot claim a royal visit, (excepting Princess Victoria’s fleeting presence) the village has clearly been keen in the past to show its loyalty, and nor have its inhabitants been averse to throwing a party given a right royal excuse. An early example of a royal connection appears in the Northampton Mercury newspaper of March 28th, 1789. King George III is famous for his problems with ill-health, specifically mental health, and in 1789 there was much concern and behind the scenes intrigue to replace him with his son, the Prince of Wales. However, on this occasion the King recovered, prompting much celebration (and relief) in the country. In the clipping below from the Northampton Mercury of March 28th, you will find the people of Great Linford amongst those rejoicing at his recovery. Such a shame that the newspaper, for “want of room”, could not furnish the particulars of the “rejoicings” that took place. The coronation of Queen Victoria, 1838Of equal paucity is the following account of the festivities at Great Linford on the occasion of Queen Victoria’s coronation, though it’s hard not to smile at the idea of being, “regaled with good old English cheer”, whatever that may have been. Liquid libation springs to mind. Victoria's Golden Jubilee of 1887Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee was officially celebrated on June 21st and 22nd, 1887, with Great Linford choosing to mark the occasion on the 21st, a Monday. The extensive account of the festivities carried in Croydon’s Weekly Standard newspaper reveals it was quite the blow-out, with a whole roasted ox being the piece de resistance. Preparations had begun in earnest the day before, when the 60 stone animal, “was conveyed on a spit to the huge fire-place erected expressly in its honour” in the manor grounds. Relays of spit turners and basters were on hand to ensure the even cooking of the great carcass, a process that took all of 24 hours. The inhabitants of the village were aroused at 5am by the peeling of the church bells, and were soon up and busy, putting up decorations and hanging flags. At 12 O’clock the Wolverton Brass Band arrived, playing “The roast beef of old England”, originally written by Henry Fielding for his play The Grub-Street Opera, and first performed in 1731. Invitations had gone out on cards from Mrs Uthwatt to all the men and boys of the village over the age of fourteen. It seems that this was a men-only affair, with over 160 soon sat at tables arranged by the publican of the Black Horse Inn. The roast beef was carved and beer distributed from a hogshead (a barrel of approximately 250 litres) which had been placed in the shade inside the gates. One presumes that it was the womenfolk of the village who had taken on the serving duties, but with the dinner and beer consumed, toasts proposed and the national anthem played, it was finally their turn to enjoy a repast of their own. At 4pm, all the women and girls of the village over fourteen years of age (numbering approximately 120 persons) proceeded to a large marquee, where they too were able to partake of the roast beef, plus mutton, while being regaled by the band. At 5pm the village adjourned to a nearby field, where a variety of games were played, the last race of the day requiring the competitors to swim the canal, twice! At 8.30, the children were provided cake, bread and butter and milk, and after a final rendition of the national anthem and 3 cheers for the organisers, the day came to a satisfying end. All in all, it sounds like a day not likely to be forgotten by the villagers. Victoria's Diamond Jubilee of 1897The diamond jubilee was celebrated in equally grand style, though lacking the impressive centrepiece of a whole roast ox. The village was alive in the early hours with the sound of hammering as two roomy tents were prepared, and the gates to the manor were transformed into an arch festooned with flowers and evergreens and a crown perched atop its summit. After a loud rendition of the national anthem, lunch was served in the manor grounds, with cold beef, mutton and ham on offer, plus salad, cheese, lemonade and beer. As per the previous jubilee festivities, games including races rounded off the day, though on this occasion it appears no-one was required to swim the canal. The Victoria memorialThe impressive Victoria Memorial that stands at the end of The Mall in London was funded from a variety of sources, including public donations. Hence, we find an account in the Globe newspaper of June 3rd, 1901, that tells us that the sum of £13 and 16 shillings was donated by Great Linford Parish Church. The death of King Edward VIIIn a headline noting the passing of the king, the Bucks Standard of May 28th, 1910, provides some illuminating details of the memorial service held in the church. The coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, 1953Television was still a relatively new innovation in 1953, but it is no surprise to learn that the broadcast of the coronation would attract much interest. The BBC website states that 20 million people watched the ceremony in the UK, though there were only approximately 2 million television sets. Many crowded into homes and institutions lucky enough to have a set of their own, which was just the case in Great Linford, with the Rectory Nursing Home throwing open its doors to the pensioners of the village. The Wolverton Express of June 5th, carried the following account of the festivities in the village. Plenty of royal connections then for Great Linford, and doubtless more to be discovered.

0 Comments

|

About this blogA place for interesting nuggets of information about Great Linford. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

- Home

- About Great Linford

- Education

- Great LInford Manor Park

- Industry & Commerce

- Law & Order

- The Manor

-

People

- Harry Bartholomew

- The Cole Family

- Kizby and Kezia Rainbow >

- The Meads

- Reverend Richard Napier

-

Uthwatt, Kings Andrewes & Bouverie

>

- John Uthwat (?-1674)

- Daniel King (1670-1716)

- Richard Uthwatt (1658-1719)

- Richard Uthwatt (1699-1731)

- Thomas Uthwatt (1693-1754)

- Henry Uthwatt (1728-1757)

- Frances Uthwatt (1728-1800)

- Rev Henry Uthwatt Andrewes (1755-1812)

- Henry Andrewes Uthwatt (1787-1855)

- Reverend William Andrewes Uthwatt (1793-1877)

- Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt (1798-1885) >

- William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921)

- William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1898-1954)

- Stella Katherine Andrewes Uthwatt (1910-1996)

- Other notable Uthwatts

- The Ward & Robe Families

- Sir William Prichard and family >

- Places

- Politics

-

Religion

- Sport

- Visiting

- Blog

|

Winner of

2023 Robert Excell Heritage Award Presented by Milton Keynes Heritage Association |

- Home

- About Great Linford

- Education

- Great LInford Manor Park

- Industry & Commerce

- Law & Order

- The Manor

-

People

- Harry Bartholomew

- The Cole Family

- Kizby and Kezia Rainbow >

- The Meads

- Reverend Richard Napier

-

Uthwatt, Kings Andrewes & Bouverie

>

- John Uthwat (?-1674)

- Daniel King (1670-1716)

- Richard Uthwatt (1658-1719)

- Richard Uthwatt (1699-1731)

- Thomas Uthwatt (1693-1754)

- Henry Uthwatt (1728-1757)

- Frances Uthwatt (1728-1800)

- Rev Henry Uthwatt Andrewes (1755-1812)

- Henry Andrewes Uthwatt (1787-1855)

- Reverend William Andrewes Uthwatt (1793-1877)

- Augustus Thomas Andrewes Uthwatt (1798-1885) >

- William Francis Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1870-1921)

- William Rupert Edolph Andrewes Uthwatt (1898-1954)

- Stella Katherine Andrewes Uthwatt (1910-1996)

- Other notable Uthwatts

- The Ward & Robe Families

- Sir William Prichard and family >

- Places

- Politics

-

Religion

- Sport

- Visiting

- Blog

RSS Feed

RSS Feed